Lavinia Fontana stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Western art. Emerging during the vibrant, yet socially restrictive, late Italian Renaissance and early Baroque periods, she transcended the conventional limitations placed upon women of her era to become arguably the first female artist to achieve sustained professional success outside the confines of a court or convent. Operating primarily in Bologna and later in Rome, Fontana built a formidable career, renowned for her sensitive portraiture, compelling religious narratives, and groundbreaking mythological scenes. Her life and extensive body of work not only demonstrate exceptional artistic talent but also illuminate the challenges and triumphs of a woman navigating the male-dominated art world of 16th and 17th-century Italy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Lavinia Fontana was born in Bologna on August 24, 1552. Her artistic destiny was perhaps set from birth, as she was the daughter of Prospero Fontana (c. 1512–1597), a prominent painter of the Bolognese School and a respected teacher. Prospero was a significant figure in the Mannerist style, having worked in Rome and Florence before establishing himself in Bologna. He ensured his daughter received not only a thorough artistic training within his own workshop but also a comprehensive humanist education, unusual for women at the time, which likely included literature, music, and classical studies.

This dual education proved invaluable. Her artistic training under Prospero provided her with a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the prevailing Mannerist aesthetic, characterized by elegant figures, complex poses, and sophisticated colour palettes. Her broader education equipped her with the intellectual tools and social graces necessary to engage with the learned patrons and complex theological or mythological subjects she would later depict. Bologna itself, a thriving university city and papal territory, offered a stimulating environment rich in artistic activity and intellectual discourse.

Fontana's earliest works, often small devotional paintings or portraits, clearly show her father's influence. They exhibit the careful draughtsmanship, elongated figures, and refined finish typical of late Mannerism. However, even in these initial stages, hints of her own developing sensibility – a particular attention to detail and a nascent naturalism – began to emerge, setting the stage for her independent artistic journey. She quickly absorbed the technical skills required, mastering oil painting on various supports, including canvas and copper, the latter allowing for exceptionally fine detail.

Developing an Independent Style

While Prospero Fontana provided the initial framework, Lavinia quickly began to forge her own artistic identity. She skillfully blended the sophisticated elegance inherited from her father's Mannerism with a keen observational naturalism, particularly influenced by the art of Northern Italy and potentially Flemish realism, known for its meticulous attention to texture and detail. This synthesis became a hallmark of her style, especially evident in her portraiture.

Her ability to render luxurious fabrics – silks, velvets, lace – and intricate jewellery with astonishing verisimilitude became legendary. This was not mere surface decoration; it served to convey the status and wealth of her sitters, an essential aspect of portraiture in this period. Yet, beyond the lavish details, Fontana possessed a remarkable talent for capturing the psychological presence of her subjects. Her portraits often reveal a sensitivity and individuality that transcends mere likeness, suggesting a genuine engagement with the sitter's personality.

Compared to her father's sometimes more formulaic Mannerism, Lavinia's work often displayed a greater warmth and directness. She looked closely at the works of earlier North Italian masters like Correggio and Parmigianino, whose soft modelling and graceful figures informed her approach, particularly in religious and mythological subjects. The rich colour palette often seen in her work also suggests an awareness of the Venetian school, perhaps artists like Titian or Veronese, known for their chromatic brilliance and textural richness.

Portraiture: A Path to Success

Portraiture became the cornerstone of Lavinia Fontana's early and sustained success. In 16th-century Bologna, a city with a wealthy noble class and a prominent university community, there was a significant demand for portraits. Fontana excelled in this genre, securing commissions from Bolognese noblewomen, scholars, and visiting dignitaries. Her gender may have even been an advantage in securing commissions from female patrons, who perhaps felt more comfortable sitting for a woman artist.

Her portraits of Bolognese noblewomen are particularly noteworthy. Works like the Portrait of a Noblewoman (c. 1580, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C.) exemplify her skill. The sitter is presented with quiet dignity, adorned in elaborate attire rendered with exquisite detail, from the intricate lace of her ruff to the gleam of her pearls. Fontana masterfully balances the depiction of status through clothing and jewels with a subtle portrayal of the sitter's inner life, conveyed through a direct yet reserved gaze.

Fontana also painted numerous self-portraits throughout her career, which are fascinating documents of her self-perception as both a woman and a professional artist. The Self-Portrait at the Spinet (1577, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome), painted around the time of her marriage, shows her not with the tools of her trade, but as a cultured woman engaged in music, perhaps emphasizing her refinement and suitability for marriage. Conversely, later self-portraits often depict her holding a brush or maulstick, confidently asserting her identity as a painter. These works were strategic tools, showcasing her skills and respectability to potential patrons.

Marriage, Family, and Professional Life

In 1577, Lavinia Fontana married Gian Paolo Zappi (also spelled Zappa or Zappi), a minor nobleman from Imola who was also a painter, likely having studied with Prospero Fontana. Their marriage was unconventional for the time. Recognizing his wife's superior talent and earning potential, Zappi largely relinquished his own artistic ambitions to act as her agent, manage the household, and assist in the studio, perhaps painting backgrounds or drapery in some works. This arrangement allowed Lavinia to focus on her prolific artistic production while also fulfilling societal expectations of marriage and motherhood.

The couple had an astonishing eleven children, though tragically only three seem to have survived past infancy. Balancing the demands of such a large family with a thriving artistic career that involved meeting deadlines, negotiating contracts, and maintaining relationships with powerful patrons must have been incredibly challenging. Fontana's ability to manage these competing demands speaks volumes about her determination, organization, and the crucial support provided by her husband.

Her success was remarkable. She became the primary breadwinner for her family, a role reversal that was highly unusual in the 16th century. Her workshop became a successful enterprise, and she commanded substantial fees for her work. She was not merely painting for pleasure or supplemental income; she was a true professional, managing a business and supporting her family through her art, setting a precedent for future generations of women artists like Artemisia Gentileschi and Elisabetta Sirani.

Expanding Horizons: Religious and Mythological Works

While portraiture provided financial stability, Fontana harboured ambitions in the more prestigious genres of religious and mythological painting. These large-scale narrative works were considered the highest form of art, typically dominated by male artists due to the need for extensive knowledge of theology, literature, and human anatomy (including the study of the nude), as well as the physical demands of working on large canvases or frescoes.

Fontana successfully broke into this domain, receiving numerous commissions for altarpieces and devotional paintings for churches and private chapels in Bologna and beyond. One notable example is the Holy Family with the Sleeping Christ Child (1589), commissioned for the Escorial in Spain by King Philip II's representative, demonstrating her international reach. Another significant public commission was the Martyrdom of St. Stephen, a large altarpiece for the church of San Paolo fuori le Mura in Rome (though painted earlier, likely around 1585-1590, while still primarily based in Bologna). These works showcased her ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and convey dramatic religious narratives.

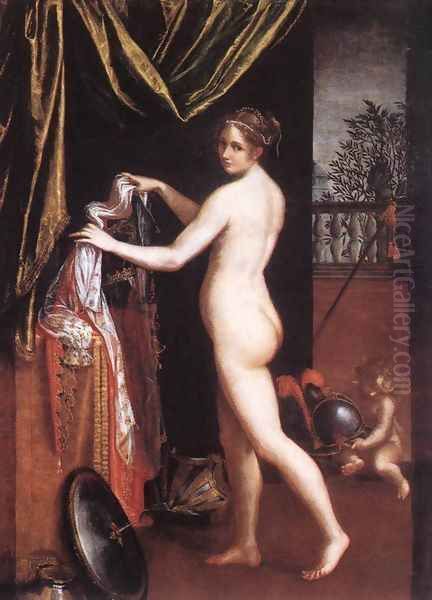

Perhaps most daringly, Fontana tackled mythological subjects, including female nudes – a genre almost entirely exclusive to male artists at the time. Her series of paintings featuring Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and the arts, are particularly significant. Works like Minerva Dressing (1613, Galleria Borghese, Rome) depict the goddess in the nude, showcasing Fontana's mastery of the female form. While perhaps drawing inspiration from classical sculpture and contemporary male artists' depictions, her approach often feels distinct, perhaps less overtly eroticized and more focused on the goddess's attributes of wisdom and strength. These works were a bold assertion of her capabilities and her right to engage with the full spectrum of artistic themes.

The Move to Rome and Papal Patronage

Around 1603, seeking broader opportunities and patronage, Lavinia Fontana moved with her family to Rome. This was a significant step, placing her at the very centre of the Italian art world, a city teeming with artistic innovation and intense competition. The move proved highly successful. She quickly gained favour at the papal court, particularly under Pope Clement VIII Aldobrandini and later Pope Paul V Borghese.

Her reputation preceded her, and she received prestigious commissions from Roman nobility and high-ranking clergy. Cardinal Scipione Borghese, Pope Paul V's nephew and an avid art collector, became an important patron. Her work Minerva Dressing entered his collection and remains in the Galleria Borghese today. In Rome, she continued to produce portraits, religious paintings, and mythological scenes, adapting her style slightly to absorb the influences of the burgeoning Baroque movement, particularly the dramatic lighting associated with Caravaggio, though she never fully abandoned her Mannerist roots or her meticulous attention to detail.

A significant honour bestowed upon her in Rome was her election to the Accademia di San Luca, the city's prestigious academy of artists, in 1611. Membership was a mark of high professional esteem, and her inclusion as a woman was exceptional. This official recognition cemented her status as one of the leading artists working in Rome at the time. Her Roman period represents the culmination of her career, demonstrating her ability to thrive and gain recognition in the most competitive artistic environment in Europe.

Artistic Influences and Connections

Lavinia Fontana's artistic development was shaped by a rich tapestry of influences. Her father, Prospero Fontana, provided the Mannerist foundation. She absorbed the grace of Correggio and Parmigianino, masters of the nearby Emilian school. The meticulous detail in her work suggests an appreciation for Flemish painting, possibly known through prints or imported works. The vibrant colours and textural richness point towards the influence of the Venetian school, particularly masters like Titian and Paolo Veronese.

In Bologna, she was contemporary with the Carracci family – Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci – who were spearheading a reform of painting, moving away from late Mannerism towards a more naturalistic, emotionally direct style that would form the basis of the Baroque. While Fontana's style remained distinct, she undoubtedly engaged with the artistic currents swirling around the Carracci Academy. Her emphasis on naturalistic detail, particularly in portraiture, resonated with some aspects of their reforms, even if her overall aesthetic retained more Mannerist elegance.

In Rome, she encountered the revolutionary art of Caravaggio, whose dramatic use of chiaroscuro (light and shadow) was transforming painting. While Fontana never became a 'Caravaggista', some of her later works show a heightened sense of light and shadow, suggesting an awareness and selective absorption of his innovations. She also certainly knew of the work of Sofonisba Anguissola, another pioneering female artist who had achieved international fame primarily as a court portraitist decades earlier. Anguissola served as an important precedent, demonstrating that a woman could achieve artistic renown, although Fontana's career path as an independent professional in major cities was different and, in many ways, more groundbreaking for the era.

Contemporaries and the Bolognese School

Lavinia Fontana emerged from the artistic milieu of late 16th-century Bologna, a city with a strong artistic tradition. Her father, Prospero, was a central figure in the local school. Other notable Bolognese painters active during her early career included Denys Calvaert, a Flemish painter who ran a successful workshop, and Bartolomeo Passerotti, known for his portraits and genre scenes. These artists contributed to the Mannerist environment in which Fontana initially trained.

The most significant development during Fontana's time in Bologna was the rise of the Carracci. Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale established their Accademia degli Incamminati around 1582, advocating for a return to naturalism, drawing from life, and studying the High Renaissance masters. Their influence became dominant in Bologna and spread to Rome, shaping the future of Italian Baroque painting. While Fontana operated independently and maintained her distinct style, she was part of this dynamic artistic landscape. Her success alongside the Carracci demonstrates the vitality and diversity of the Bolognese school at this time.

After Fontana moved to Rome, the Bolognese school continued to flourish, producing major Baroque artists who had trained with or been influenced by the Carracci, such as Guido Reni, Domenichino, and Francesco Albani. Fontana's earlier success in Bologna helped pave the way, demonstrating the city's capacity to nurture exceptional talent, including that of a woman artist operating at the highest professional level.

Later Life and Legacy

Lavinia Fontana continued to work actively in Rome until shortly before her death. Her later years were marked by continued professional success and recognition, but also, according to some accounts, by increased religious devotion. Some sources suggest she experienced a form of 'spiritual crisis' or mystical experience, leading her and her husband to affiliate with a lay religious community or spend time in monastic retreat near the end of her life, though she seems to have continued painting.

She died in Rome on August 11, 1614, at the age of 62, and was buried with honours. Her career spanned over four decades, and her known oeuvre includes over 135 documented works, with more than 100 surviving today – the largest body of work by any female artist before the 18th century. This prolific output attests to her dedication, skill, and the consistent demand for her art.

Lavinia Fontana's legacy is profound. She was a true pioneer, the first woman to manage a large, independent professional workshop and build a career comparable in scope and public recognition to her male contemporaries. She demonstrated that women could master all genres of painting, including large-scale public commissions and the nude. Her success provided an inspiring model for subsequent generations of female artists, including Artemisia Gentileschi in Rome and Naples, and Elisabetta Sirani in Bologna, who consciously built upon the path Fontana had forged. She proved that talent, ambition, and professionalism could overcome significant societal barriers.

Conclusion: A Trailblazer Remembered

Lavinia Fontana's journey from the workshop of her father in Bologna to the papal court in Rome is a testament to her extraordinary talent and unwavering determination. In an era when women's roles were severely circumscribed, she carved out a space for herself as a leading professional artist, competing successfully with her male peers and achieving widespread acclaim. Her mastery of portraiture captured the likenesses and status of her patrons with unparalleled detail and sensitivity, while her ventures into religious and mythological painting demonstrated her ambition and technical prowess in the most esteemed genres.

More than just a skilled painter, Fontana was a trailblazer who fundamentally challenged the gendered limitations of the art world. Her prolific output, her management of a successful workshop, her election to the Roman Academy, and her ability to balance a demanding career with family life collectively mark her as a figure of immense historical importance. Lavinia Fontana not only enriched the artistic landscape of the late Renaissance and early Baroque but also opened doors for the women artists who would follow, leaving an indelible mark on the history of art. Her work continues to be studied and admired, securing her place as a crucial figure in the narrative of Western art and a pioneering force for women in the creative professions.