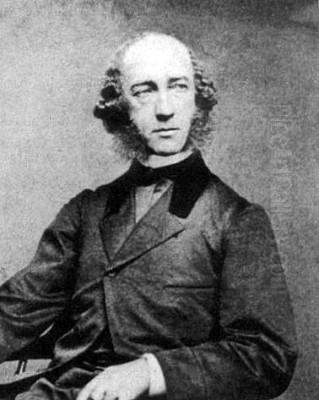

Martin Johnson Heade stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 19th-century American art. Born on August 11, 1819, in the rural community of Lumberville, Pennsylvania, he navigated a path distinct from many of his contemporaries. While associated with major movements like the Hudson River School and Luminism, Heade cultivated a deeply personal style characterized by meticulous detail, a profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and an unusual range of subjects, from haunting salt marsh landscapes to vibrant tropical hummingbirds and sensuous floral still lifes. His long career, spanning over six decades until his death on September 4, 1904, produced a body of work that was largely overlooked during his lifetime but has since earned him recognition as one of America's most original and important painters.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Heade's origins were relatively modest; he was the son of a storekeeper in a small farming town along the Delaware River. His earliest artistic training came from a neighbor, the renowned folk painter Edward Hicks, famous for his numerous versions of The Peaceable Kingdom. This initial instruction likely instilled a respect for clear delineation and composition, though Hicks's naive style contrasts sharply with Heade's later sophisticated realism. Heade may have also briefly studied with Thomas Hicks, a cousin of Edward, who pursued a more academic portrait style. Unlike many aspiring artists of his generation, Heade did not receive formal academic training in the established art academies of the time.

His professional career began around the age of twenty, initially focusing on portraiture. Like many young artists seeking commissions, he became an itinerant painter, traveling through various American towns and cities. His earliest known works date from the late 1830s, and he first exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 1839. Seeking to refine his skills, Heade embarked on the first of several trips abroad, visiting Europe around 1840. He spent time in Rome, and likely visited France and England, studying Old Masters and absorbing the European artistic traditions, a common practice for ambitious American artists aiming to elevate their craft beyond provincial limitations.

Throughout the 1840s and early 1850s, Heade continued to work primarily as a portraitist, achieving a degree of competence in capturing likenesses. He painted notable figures, including military and political leaders, demonstrating a solid, if not yet highly distinctive, technique. However, his restless nature kept him moving, preventing him from settling long in one place or becoming closely associated with a specific regional school during these formative years.

A Shift Towards Landscape: New York and the Hudson River School Influence

A significant turning point occurred in the mid-1850s when Heade began to shift his focus from portraiture to landscape painting. Around 1859, he took up residence in New York City, placing himself at the epicenter of the American art world. He took a studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building, which housed many leading artists of the day, including prominent figures of the Hudson River School such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford. Exposure to their work and the prevailing artistic currents undoubtedly influenced Heade.

The Hudson River School, often considered the first coherent school of American art, was founded by artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. They celebrated the American wilderness, depicting majestic mountains, serene lakes, and dramatic natural vistas, often imbued with a sense of national pride and spiritual significance. Heade absorbed some of their interest in detailed rendering and the grandeur of nature. His early landscapes sometimes echoed the compositional structures and detailed foregrounds favored by Durand or the dramatic effects sought by Cole.

However, Heade quickly diverged from the mainstream Hudson River School aesthetic. While artists like Church and Bierstadt were painting monumental canvases of spectacular scenery like South American volcanoes or the Rocky Mountains, Heade became increasingly drawn to quieter, more intimate, and often overlooked aspects of the landscape. He developed a particular fascination with the coastal salt marshes of New England, subjects that would become one of his most enduring and recognizable themes.

The Lure of the Marshes: Luminism and Atmosphere

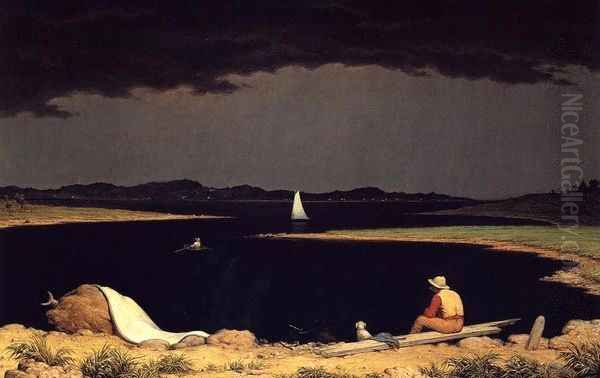

Heade's salt marsh paintings, begun in the late 1850s and continuing throughout his career, represent a significant departure from typical Hudson River School subjects. Instead of mountains or forests, he depicted the flat, expansive wetlands stretching along the coasts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Jersey. These works are characterized by low horizons, vast, open skies, and a palpable sense of stillness and atmosphere. He often included haystacks, which dot the marshes during harvest time, providing vertical accents in the predominantly horizontal compositions.

These marsh scenes are often associated with Luminism, a style or mode within American landscape painting prominent from the 1850s to the 1870s. Luminism, practiced by artists like Fitz Henry Lane, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and John Frederick Kensett, emphasized tranquility, subtle gradations of light, and smooth, often invisible brushwork to create serene, contemplative moods. Heade's marshes certainly share these qualities: the meticulous rendering of light reflecting off water, the hazy diffusion of sunlight or moonlight, and the profound quietude that pervades many of these scenes.

Yet, Heade's marshes are not always serene. He frequently depicted the dramatic effects of weather, particularly approaching thunderstorms. Works like Approaching Thunderstorm (1859) or Sudden Shower, Newbury Marshes capture the tension and eerie light preceding a storm, with dark, heavy clouds contrasting sharply with brightly lit portions of the landscape. This infusion of drama and psychological intensity sets his work apart from the more consistently placid canvases of Lane or Kensett. Heade masterfully used light and shadow not just for descriptive purposes but to evoke specific emotional responses, ranging from peaceful solitude to unsettling anticipation. His marsh paintings are studies in subtlety, capturing the transient effects of light and weather on a seemingly monotonous landscape, revealing its hidden beauty and complexity.

Tropical Dreams: Hummingbirds, Orchids, and South America

Driven perhaps by a desire for new subjects or influenced by the scientific and artistic expeditions of contemporaries like Frederic Edwin Church, Heade embarked on a series of journeys to the tropics beginning in the 1860s. His first major trip was to Brazil in 1863-1864. There, he was captivated by the vibrant colors and exotic life forms, particularly hummingbirds. He conceived an ambitious project: a lavishly illustrated book titled The Gems of Brazil, which would feature chromolithographs based on his small, jewel-like paintings of hummingbirds in their natural habitats.

He painted numerous studies for this project, meticulously rendering the iridescent plumage of the tiny birds against detailed backdrops of tropical foliage. Although he exhibited some of these paintings upon his return and even received commendation from Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, the book project ultimately failed due to financial difficulties and Heade's concerns over the quality of the proposed reproductions and potential copyright issues. While the failure was a disappointment, it freed him to develop these tropical themes in larger, more complex compositions.

Heade made two further trips to the tropics: to Nicaragua in 1866, and to Colombia, Panama, and Jamaica in 1870. These journeys provided him with a rich store of sketches and inspiration. He began combining hummingbirds with another exotic subject: orchids. His paintings pairing specific hummingbird species with lush, blooming orchids became another signature theme. These works, such as Passion Flowers and Hummingbirds or compositions featuring Cattleya orchids, are remarkable for their synthesis of scientific accuracy and artistic sensibility.

Unlike the purely scientific illustrations of John James Audubon, Heade's bird and flower paintings are imbued with a sense of drama and sensuousness. The orchids are often depicted with an almost palpable texture, their complex forms rendered in meticulous detail. The hummingbirds hover nearby, their vibrant colors flashing against the foliage. Art historians have noted the potential symbolism in these pairings, suggesting themes of fragility, beauty, exoticism, and even subtle eroticism, reflecting Victorian fascinations with the natural world and its hidden meanings. These tropical paintings showcase Heade's exceptional skill in detailed rendering and his ability to create compositions that are both scientifically observed and artistically compelling.

Mastery of Still Life: Flowers on Velvet

Alongside his landscapes and tropical scenes, Heade also excelled in the genre of still life, particularly floral subjects. While he painted arrangements in vases, he became especially known for his depictions of single blossoms or small clusters, often laid horizontally on a piece of velvet cloth. His favorite subject in this format was the magnolia, particularly the Magnolia grandiflora native to the American South.

Paintings like Giant Magnolias on a Blue Velvet Cloth exemplify this genre. Heade rendered the thick, waxy petals of the magnolias with extraordinary realism, capturing their creamy white texture and the subtle play of light across their surfaces. The dark, rich velvet background serves to highlight the luminosity and sculptural quality of the flowers. These still lifes possess a distinct sensuousness and intensity. Sometimes, a single fallen petal or a slightly browning edge hints at the transience of beauty, adding a layer of poignant meaning.

Heade also painted other flowers, including roses (Jacqueminot Roses, Cherokee Roses in a Glass Vase), apple blossoms, and orchids, often employing the same format of placing them against a dark, luxurious fabric. These works demonstrate his versatility and his consistent preoccupation with the effects of light on texture and form. His still lifes stand apart from the more elaborate, multi-object arrangements common in earlier American still life traditions, focusing instead on the inherent beauty and evocative power of the individual flower.

Later Years in Florida

In 1883, at the age of 64, Heade married and settled in St. Augustine, Florida. This move marked the final phase of his life and career. Florida's subtropical environment provided him with ready access to the landscapes and flora that had long fascinated him. He continued to paint Florida landscapes, often featuring palm trees and waterways bathed in the warm Southern light, as seen in works titled Florida Landscape. He also continued producing his popular floral still lifes, particularly magnolias, which grew abundantly in the region.

In St. Augustine, Heade became a respected member of the local community. He associated with the wealthy industrialist and developer Henry Morrison Flagler, who was transforming St. Augustine into a major winter resort. Flagler became an important patron, purchasing several of Heade's works for his luxurious Ponce de Leon Hotel. Despite this local recognition and patronage, Heade remained largely outside the mainstream national art scene during these later years. He continued to paint prolifically until his death in St. Augustine in 1904.

Artistic Style Revisited: A Unique Blend

Martin Johnson Heade's style is difficult to categorize neatly. It incorporates elements of several major 19th-century movements but ultimately remains distinctively his own. His work clearly shows the influence of Romanticism in its emphasis on emotion, atmosphere, and the power of nature, particularly evident in his storm scenes and evocative marsh landscapes. The meticulous detail and objective observation seen in his hummingbirds, orchids, and still lifes align him with Realism.

His handling of light, especially in the marsh scenes, connects him strongly to Luminism. He shared with artists like Lane and Gifford an interest in capturing the subtle effects of light and atmosphere, often achieving a sense of profound stillness and transcendence. However, Heade's frequent inclusion of dramatic weather and his unique subject matter—the marshes themselves, the tropical birds and flowers—distinguish his work. Unlike the epic scale favored by Church or Bierstadt, Heade often focused on more intimate, specific aspects of nature, rendered with an intensity that could be both beautiful and unsettling. His brushwork, while often smooth in the Luminist manner, could also be more varied and textured, particularly in his floral still lifes.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Despite his prolific output and unique vision, Martin Johnson Heade faded into relative obscurity after his death. His work did not fit easily into the dominant narratives of American art history being written in the early 20th century, which tended to focus on the grander achievements of the Hudson River School or the later innovations of Impressionism and Modernism.

Heade's rediscovery began in the 1940s, spurred by curators and scholars associated with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who recognized the proto-Surrealist qualities in the intense realism and sometimes strange juxtapositions in his work (like hummingbirds hovering near oversized orchids). An exhibition at MoMA in 1944 helped bring his name back into circulation.

The pivotal moment in Heade scholarship came with the work of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., whose comprehensive catalogue raisonné, first published in 1975 and revised in 2000, meticulously documented Heade's life and oeuvre. Stebbins's research firmly established Heade's importance and provided the foundation for numerous subsequent exhibitions and studies. Major retrospectives, such as those organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (which holds the largest public collection of his work), the National Gallery of Art, and the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, have further solidified his reputation.

Today, Martin Johnson Heade is widely regarded as one of the most significant American painters of the 19th century. His works are prized by museums and collectors for their technical brilliance, atmospheric depth, and unique subject matter. He is celebrated for his haunting salt marsh landscapes, which capture the subtle beauty and moods of the Eastern coastline; his vibrant and detailed tropical scenes, which blend scientific observation with artistic imagination; and his sensuous floral still lifes, which explore the beauty and transience of nature. His ability to infuse detailed realism with profound emotion and atmosphere marks him as a singular talent who forged his own path, leaving behind a rich and fascinating body of work that continues to captivate viewers. His journey from itinerant portraitist to master of landscape, tropicalia, and still life reveals a restless, searching spirit and an enduring dedication to capturing the multifaceted beauty of the natural world.