Frederic Edwin Church stands as a monumental figure in the history of American art. Active during the mid-to-late 19th century, he was a central figure in the Hudson River School, the first truly native school of landscape painting in the United States. Renowned for his breathtakingly detailed and often immense canvases depicting the natural wonders of the Americas and beyond, Church captured the spirit of an era marked by exploration, scientific discovery, and a burgeoning sense of national identity. His work, characterized by its dramatic light, meticulous detail, and sublime vistas, brought him unprecedented fame during his lifetime and continues to captivate audiences today. This exploration delves into his life, his artistic evolution, his seminal works, his contemporaries, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

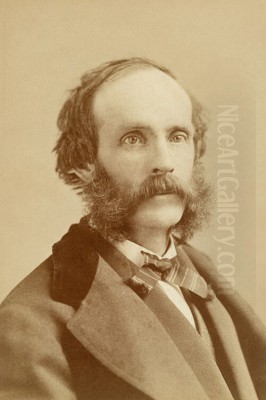

Frederic Edwin Church was born on May 4, 1826, in Hartford, Connecticut. Unlike many artists of his time who struggled for recognition and financial stability, Church hailed from a privileged background. His father, Joseph Church, was a successful silversmith and jeweler, later involved in banking and insurance, and a director at Aetna Life Insurance Company. This familial wealth provided young Frederic with the security and resources to pursue his artistic inclinations without the immediate pressure of earning a living from his art.

Recognizing his son's talent and passion, Joseph Church arranged for Frederic, at the age of eighteen, to study with the preeminent American landscape painter of the era, Thomas Cole. This apprenticeship, beginning in 1844, was a pivotal moment. Cole, widely regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School, resided in Catskill, New York, amidst the very landscapes that inspired the movement. Church became Cole's only formal pupil, living and working with him for two years.

Under Cole's tutelage, Church absorbed the foundational principles of the Hudson River School: a deep reverence for nature, the practice of sketching directly from the landscape, and the creation of large-scale studio compositions imbued with moral or historical significance. Cole encouraged detailed observation, but also the infusion of romantic sentiment and allegory into landscape painting. Church quickly proved an adept student, mastering Cole's techniques while beginning to develop his own distinct approach. He accompanied Cole on sketching trips throughout the Catskills and New England, honing his skills in capturing the nuances of the American wilderness.

By 1845, Church was already exhibiting his work, selling his first major oil painting, Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford, in 1636, to the Wadsworth Atheneum in his hometown of Hartford—an auspicious start. He was elected the youngest Associate of the prestigious National Academy of Design in 1848 and became a full Academician the following year, signaling his rapid ascent within the American art world. Cole's untimely death in 1848 marked the end of Church's formal training, but Cole's influence, particularly his love for the American landscape and his ambition to elevate landscape painting, remained a guiding force.

The Hudson River School and American Identity

To understand Frederic Edwin Church, one must understand the Hudson River School. Flourishing from roughly the 1820s to the 1870s, this movement represented America's first coherent school of art. Initially focused on the landscapes of the Hudson River Valley and surrounding areas like the Catskills, Adirondacks, and White Mountains, its scope later expanded to encompass the American West, South America, and even the Arctic. The artists associated with the school shared a common belief in the spiritual and aesthetic significance of the American landscape.

The rise of the Hudson River School coincided with a period of intense national optimism, westward expansion (Manifest Destiny), and industrial growth in the United States. Nature was seen not just as beautiful, but as a direct manifestation of God's divine plan, a source of national pride, and a defining element of American character, distinct from the cultivated landscapes and ancient ruins of Europe. Writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, proponents of Transcendentalism, articulated a philosophy that emphasized intuition, individualism, and the inherent goodness of both humanity and nature, finding divinity mirrored in the wilderness. This intellectual climate deeply informed the painters of the Hudson River School.

Thomas Cole pioneered the movement, creating allegorical landscapes like The Course of Empire and The Voyage of Life, which used nature to comment on human civilization and spirituality. The generation that followed Cole, including Church, Asher B. Durand, John F. Kensett, and Sanford Robinson Gifford, built upon his foundation. Durand, who became president of the National Academy of Design after Cole, advocated for meticulous realism and direct study from nature in his "Letters on Landscape Painting," influencing many, including Church, towards greater naturalistic detail.

Church emerged as the leading figure of the school's second generation. While deeply respectful of Cole's legacy, Church moved away from overt allegory, instead finding spiritual resonance and nationalistic sentiment within the detailed, dramatic, and often scientifically informed depiction of specific natural wonders. His work came to epitomize the ambition and confidence of mid-19th century America, presenting the continent's landscapes as both sublime spectacles and testaments to divine creation and national potential.

Journeys into the Sublime: South America

A defining characteristic of Church's career was his extensive travel in search of dramatic and exotic subject matter. His most influential journeys were to South America, undertaken in 1853 and 1857. These expeditions were directly inspired by the writings of the renowned Prussian naturalist and explorer, Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt's multi-volume work Kosmos (Cosmos), published starting in the 1840s, presented a holistic view of the universe, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all natural phenomena and advocating for a fusion of scientific observation and aesthetic appreciation. Humboldt had traveled extensively in South America decades earlier and urged artists to capture the unique physiognomy of the tropics.

Heeding Humboldt's call, Church embarked on his first South American trip in 1853, accompanied by his friend, the entrepreneur Cyrus West Field (who would later mastermind the transatlantic telegraph cable). They traveled through Colombia and Ecuador for five months, sketching volcanoes, mountains, rivers, and lush vegetation. Church was particularly captivated by the dramatic topography and atmospheric effects of the Andes. He gathered a wealth of sketches and studies that would fuel his studio paintings for years.

His second, longer trip in 1857 saw him return to Ecuador, this time accompanied by fellow landscape painter Louis Rémy Mignot. They spent ten weeks focusing on the Andean highlands, studying volcanoes like Cotopaxi and Chimborazo (which Humboldt had famously climbed) and the rich biodiversity of the region. Church meticulously documented plant life, geological formations, and the play of light and weather, filling numerous sketchbooks. These journeys provided him with the raw material for some of his most celebrated masterpieces, allowing him to depict landscapes few North Americans or Europeans had ever seen, filtered through Humboldt's lens of scientific wonder and romantic sensibility.

Confronting the Arctic Wilds and Other Travels

Church's thirst for novel and sublime landscapes was not limited to the tropics. In 1859, seeking a different kind of natural spectacle, he chartered a ship and sailed north to the waters off Newfoundland and Labrador. His companion on this voyage was the writer Rev. Louis Legrand Noble, who later chronicled their adventures in the book After Icebergs with a Painter. Church spent several weeks sketching the dramatic forms and colors of icebergs, enduring challenging conditions to capture these ephemeral giants of the North Atlantic. This expedition provided the basis for his monumental painting The Icebergs.

The timing of this trip and the subsequent painting coincided with intense public interest in Arctic exploration, particularly the ill-fated expedition of Sir John Franklin, which had vanished years earlier. Church's depiction of the Arctic tapped into this fascination with the remote, dangerous, and beautiful northern frontier.

His travels continued throughout his life. In 1865, he visited Jamaica, capturing the island's tropical beauty. A significant journey from 1867 to 1869 took him and his family to Europe and the Middle East, including stops in London, Paris, Rome, Athens, Constantinople, Damascus, Beirut, and Jerusalem. This exposure to Old World cultures and landscapes, particularly the architecture of the Near East, would profoundly influence the design of his home, Olana. Later in life, despite declining health, he made trips to Mexico in the 1880s, continuing to sketch and find inspiration in new environments. These diverse experiences enriched his visual vocabulary and solidified his reputation as America's most adventurous landscape painter.

Masterworks of Light and Detail

Frederic Edwin Church's fame rested on a series of large-scale, highly detailed, and dramatically lit canvases that became sensations upon their exhibition. These works showcased his technical virtuosity and his unique ability to combine scientific accuracy with romantic grandeur.

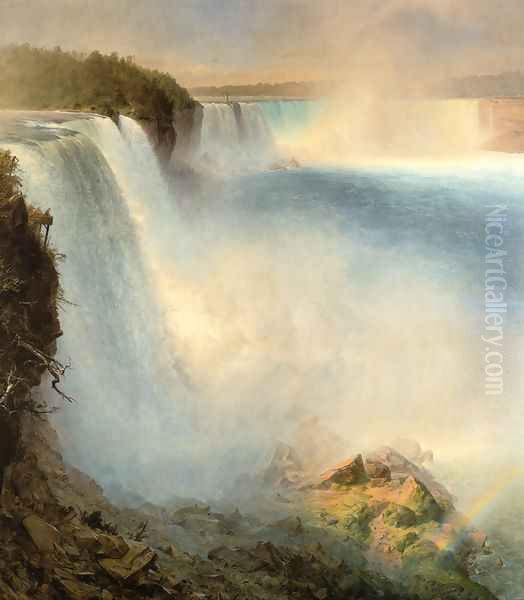

Niagara (1857): Painted after several visits to the falls, this work presented a radical, panoramic perspective from the Canadian side, just at the brink of the Horseshoe Falls. Eliminating any foreground landmass, Church immersed the viewer directly in the power and immensity of the water. The meticulous rendering of the churning rapids, the mist, and the distant rainbow became a hallmark of his style. Niagara was exhibited to great acclaim in New York and London, cementing Church's international reputation and becoming an icon of American natural power. Several versions exist, including a prominent one at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

The Heart of the Andes (1859): Arguably Church's most famous painting, this monumental work (over five by ten feet) is a composite landscape synthesizing his South American observations. It presents an idealized panorama of the Andean highlands, teeming with meticulously rendered flora and fauna, leading the eye from a lush foreground stream through valleys to snow-capped peaks (likely Chimborazo) under a luminous sky. Exhibited as a single-painting event in New York and other cities, viewers often used opera glasses to examine its intricate details. It was hailed as the greatest American painting produced to date, a perfect fusion of Humboldtian science and sublime artistry. It is now a centerpiece of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Twilight in the Wilderness (1860): This painting depicts a fiery sunset over a pristine North American landscape, likely inspired by the scenery of Maine. The intensity of the colors – blazing oranges, reds, and yellows reflected in a calm lake – creates a scene of almost apocalyptic beauty. Painted on the eve of the American Civil War, some critics have interpreted its dramatic sky as symbolic of the impending conflict or as a divine lament for a vanishing wilderness. It showcases Church's mastery of light and atmosphere at its most theatrical.

The Icebergs (1861): Based on his 1859 Arctic voyage, this large canvas portrays massive, weathered icebergs floating in a cold, clear sea. Church captures the varied textures and colors of the ice, from deep blues and greens in the shadows to brilliant whites and pinks where the light hits. A broken mast in the foreground hints at the dangers of Arctic exploration. Exhibited in New York and London during the Civil War (initially titled The North), its reception was somewhat muted compared to Heart of the Andes, perhaps due to the somber national mood. It disappeared from public view for over a century before being rediscovered in England and acquired by the Dallas Museum of Art.

Aurora Borealis (1865): This dramatic work captures the celestial phenomenon of the northern lights over a frozen Arctic landscape. Based partly on his own sketches from Labrador and partly on descriptions by Arctic explorers like Isaac Israel Hayes, the painting combines scientific curiosity with a sense of awe and mystery. The glowing aurora illuminates the ice-bound ship and dog sleds below, emphasizing the vastness and power of nature in the extreme north.

Cotopaxi (various versions, e.g., 1862): Church painted Ecuador's active volcano Cotopaxi multiple times. The 1862 version depicts the volcano erupting under a dramatic sky where the sun struggles to break through the smoke and clouds. Like Twilight in the Wilderness, its creation during the Civil War has led to interpretations of the erupting volcano as a symbol of the nation's violent conflict. These works highlight Church's fascination with geology and dramatic natural forces.

Morning in the Tropics (1877): A later work, this painting revisits the South American landscape but with a potentially calmer, more atmospheric sensibility than his earlier tropical scenes. It still demonstrates his incredible attention to detail in rendering lush vegetation and the effects of hazy, humid light filtering through the dense jungle canopy. The exact dating and titling of some of Church's tropical scenes can be complex, but this work represents his continued engagement with these themes later in his career.

These major works, often exhibited individually in darkened rooms with theatrical lighting, established Church as a master showman as well as a painter. They were public spectacles that drew huge crowds, contributing significantly to his wealth and fame.

Luminism: The Poetry of Light

While firmly rooted in the Hudson River School, Church's work, particularly from the late 1850s through the 1860s, is often associated with Luminism. Though debated by art historians as a distinct movement versus a stylistic tendency, Luminism describes a mode of American landscape painting characterized by its treatment of light and atmosphere.

Luminist paintings typically feature calm, reflective water, expansive skies, and horizontal compositions. Brushwork is often concealed, creating smooth, polished surfaces. The defining element is the meticulous rendering of light – often the soft glow of dawn or dusk – which imbues the scenes with a sense of stillness, silence, and transcendent clarity. The effect is often described as poetic, spiritual, and deeply serene, emphasizing nature's quiet grandeur rather than its turbulent drama.

Church's paintings like Niagara, parts of The Heart of the Andes, and numerous coastal scenes and sunsets demonstrate key Luminist characteristics. His precise rendering of light reflecting off water, the subtle gradations of tone in the sky, and the overall sense of atmospheric envelopment align with the style. Other painters strongly associated with Luminism include John F. Kensett, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Martin Johnson Heade, whose works often share this quiet intensity and focus on light's ephemeral effects. Church, however, often combined these serene Luminist passages with more dramatic elements, creating a unique synthesis within his grand compositions.

Olana: A Persian Fantasy on the Hudson

Beyond his paintings, Church's most personal and enduring creation is Olana, his home and estate overlooking the Hudson River in Greenport, New York, near the town of Hudson. Purchased in 1860 as a 126-acre farm, the property grew over time as Church acquired adjacent land to shape his ideal landscape. The main house, designed by Church himself after an initial collaboration with architect Calvert Vaux, is a unique architectural statement.

Construction began in 1870 and continued for several years. Deeply inspired by his travels in the Middle East, Church designed Olana as an eclectic fantasy blending Victorian architectural elements with Persian, Moorish, and other Near Eastern motifs. The house features asymmetrical massing, towers, intricate stenciling, colorful tiles, carved woodwork, and large windows strategically placed to frame stunning views of the Hudson River and the Catskill Mountains – the very landscapes that launched his career.

Church meticulously planned not only the house but the entire 250-acre landscape, creating winding carriage roads, a man-made lake, and carefully managed woodlands and fields to optimize the picturesque views. Olana became his sanctuary, family home (with his wife Isabel Carnes, whom he married in 1860, and their children), studio, and a three-dimensional work of art. He filled it with objects collected during his travels, his own sketches, and works by other artists. Today, Olana State Historic Site preserves the house, its contents, and the surrounding landscape largely as Church left it, offering invaluable insight into his life, tastes, and artistic vision.

Peers and Pupils: A Landscape of Talent

Frederic Church did not work in isolation. He was part of a vibrant community of artists, primarily associated with the Hudson River School and the New York art scene centered around the National Academy of Design and the Tenth Street Studio Building, where Church kept a studio for many years.

His primary mentor remained Thomas Cole, whose legacy shaped the entire generation. Asher B. Durand was another senior figure, whose emphasis on detailed naturalism provided a counterpoint to Cole's allegorical tendencies and clearly influenced Church's meticulous style.

Among his direct contemporaries, Albert Bierstadt emerged as his chief rival in the creation of large-scale, dramatic landscapes. While Church focused initially on the East Coast and South America, Bierstadt, often influenced by the German Düsseldorf School's style, became famous for his grand depictions of the American West, such as the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite. Both artists achieved immense popularity and commanded high prices for their work.

Other key figures included the Luminist painters John F. Kensett and Sanford Robinson Gifford, known for their more intimate and atmospheric scenes, often of coastal New England or the Catskills. Jasper Francis Cropsey specialized in vibrant autumnal landscapes. Martin Johnson Heade explored coastal marshes, thunderstorms, and, uniquely, tropical flowers often paired with hummingbirds, sometimes working in South America concurrently with Church.

Jervis McEntee, a close friend, painted more melancholic, late autumn landscapes. Worthington Whittredge was known for his detailed woodland interiors, influenced by his time in Düsseldorf but adapted to American scenes. Thomas Moran, slightly younger, followed Bierstadt west and became renowned for his spectacular paintings of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, playing a role in the establishment of National Parks. George Inness, initially associated with the Hudson River School, later evolved towards the more subjective and atmospheric styles of French Barbizon painting and Tonalism.

While Church was primarily focused on his own ambitious projects, he did have a few students. Besides his close relationship with McEntee, he offered guidance to William James Stillman, an artist, journalist, and diplomat, and Walter Launt Palmer, who became known for his Impressionist-influenced winter landscapes. Church's influence, however, extended far beyond direct tutelage, setting a standard for technical excellence and ambition that impacted nearly every landscape painter of his generation.

Exhibitions, Acclaim, and the Market

Church achieved a level of fame and financial success rare for an American artist of his time. He exhibited regularly at the National Academy of Design and other major venues. His strategy of unveiling major works like Niagara, The Heart of the Andes, and The Icebergs as single-painting exhibitions proved immensely successful. These shows often traveled to multiple cities, including internationally to London, and charged admission, becoming major cultural events that drew thousands of paying visitors.

The press lauded his work, often using superlatives to describe his technical skill and the sublime power of his subjects. Critics praised his ability to combine minute detail with panoramic scope, and his paintings were seen as embodying the nation's spirit and potential. He commanded unprecedented prices for his canvases, attracting wealthy patrons such as William T. Walters of Baltimore and Samuel Colt of Hartford. By the 1860s, Church was arguably the most famous and financially successful painter in America.

However, artistic tastes began to shift in the 1870s and 1880s. The rise of French Barbizon painting, with its looser brushwork and emphasis on mood over detail (popularized in America by artists like George Inness), and the subsequent arrival of Impressionism, began to make the meticulous realism of the Hudson River School seem old-fashioned to some critics and collectors. While Church continued to paint and exhibit, his popularity gradually waned from its peak.

Despite this relative decline during his later years, interest in Church's work was revived in the 20th century, particularly from the mid-century onwards, as art historians and museums reassessed 19th-century American art. Major retrospective exhibitions, such as the one organized by the National Gallery of Art in 1989 titled Frederic Edwin Church, traveled to multiple venues and reintroduced his spectacular canvases to a modern audience, solidifying his place in the canon of American art. Other significant exhibitions featuring his work, like A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting, 1760–1910 (1983-84), which traveled to Boston, Washington, and Paris, further highlighted his importance.

Later Years: Shadows and Persistence

The later decades of Church's life brought challenges. In the late 1870s, he began suffering severely from inflammatory rheumatism. This painful condition increasingly afflicted his right arm and hand, making the meticulous brushwork required for his large, detailed canvases extremely difficult. Ever determined, Church taught himself to paint with his left hand, though he inevitably produced fewer large-scale oil paintings.

His focus shifted somewhat during these years. He devoted considerable energy to designing and refining the landscape around Olana, viewing the estate itself as an artistic creation. He continued to travel when his health permitted, notably to Mexico, and produced numerous oil sketches and smaller works. He also worked in mediums less demanding than large oils, such as drawings.

Although his critical standing had diminished from its zenith in the 1860s, he remained a respected figure in the art world. He spent winters in warmer climates, often in Mexico, and summers at Olana. Frederic Edwin Church died on April 7, 1900, in New York City, at the home of his friend and patron William E. Dodge. He was buried in the Spring Grove Cemetery in his hometown of Hartford, Connecticut. His death marked the end of an era for American landscape painting. A period of relative obscurity followed for much of the Hudson River School, before its significant revival in the later 20th century.

Enduring Legacy: Nature, Science, and the American Soul

Frederic Edwin Church left an indelible mark on American art and culture. As a leading painter of the Hudson River School, he helped define a national artistic identity rooted in the continent's unique and spectacular natural landscapes. His work celebrated the beauty, power, and spiritual significance of the wilderness, resonating deeply with the spirit of 19th-century America.

His technical mastery remains astounding. The combination of panoramic scale with intricate detail, the dramatic rendering of light and atmosphere, and the sheer ambition of his major canvases set a high bar for landscape painting. His integration of scientific observation, inspired by Humboldt, with romantic sensibility offered a unique vision of nature as both a subject of empirical study and a source of profound awe and emotion.

Church's influence extended to his contemporaries and followers within the Hudson River School and Luminism. His success also demonstrated the potential for American artists to achieve international recognition and significant financial reward. His innovative single-painting exhibitions influenced how art was presented and marketed to the public. Furthermore, his spectacular, detailed, and often panoramic compositions arguably prefigured and influenced the development of landscape photography and even cinematic depictions of nature.

Today, Church's works are prized possessions of major museums across the United States and beyond, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Wadsworth Atheneum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (which holds many Olana-related drawings), and of course, Olana State Historic Site itself. His paintings continue to be studied for their artistic technique, their reflection of 19th-century American culture, their engagement with science and exploration, and their enduring power to evoke the sublime beauty of the natural world.

Conclusion

Frederic Edwin Church was more than just a landscape painter; he was an explorer, a showman, a technical virtuoso, and a visionary who captured the essence of the American landscape on a grand scale. From the Catskills to the Andes, from Niagara Falls to Arctic icebergs, he translated the natural wonders of the world into breathtaking canvases that fused meticulous realism with romantic grandeur. His life's work, including his extraordinary home Olana, stands as a testament to his unique talent and ambition. As a central figure of the Hudson River School and a master of light and detail, Church played a pivotal role in shaping American art, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire awe and admiration.