Martin Schongauer stands as a colossus in the landscape of Northern European art during the late 15th century. Primarily celebrated as an engraver but also accomplished as a painter, he operated during a pivotal period of transition, bridging the intricate elegance of the Late Gothic style with the burgeoning naturalism and technical innovations of the Northern Renaissance. His work, particularly his masterful copperplate engravings, achieved unprecedented levels of refinement and expressive power, setting a standard that profoundly influenced subsequent generations of artists, most notably Albrecht Dürer. Born and primarily active in Colmar, Alsace, Schongauer's artistry radiated outwards, leaving an indelible mark across Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain.

Origins and Artistic Formation

The precise details surrounding Martin Schongauer's birth remain somewhat debated among historians, though a consensus leans towards a date around 1445 to 1450. He was born in Colmar, a vibrant town in the Upper Rhine region, which was then part of the Holy Roman Empire. His family background provided a fertile ground for artistic development. His father, Caspar Schongauer, was a respected goldsmith who had relocated to Colmar from Augsburg. This connection to metalworking is often cited as a crucial factor in Martin's later mastery of engraving, a technique demanding intricate work on copper plates, akin to the skills of a goldsmith.

Schongauer's formal artistic training is not definitively documented, leading to speculation. It is highly probable that he received initial instruction in his father's workshop, learning the fundamentals of drawing and metal manipulation. Beyond this, his stylistic development strongly suggests exposure to the leading artistic currents of his time, particularly the sophisticated realism of Early Netherlandish painting. The influence of Flemish masters, especially the great Rogier van der Weyden, is palpable in the elegant figural types, complex drapery, and emotional depth found in Schongauer's work.

Whether Schongauer traveled to the Netherlands to study directly under Van der Weyden or absorbed these influences through circulated artworks remains uncertain. Some scholars propose a period of travel during his formative years, potentially including time in Burgundy or Flanders. Regardless of the exact mechanism, the stylistic dialogue with Netherlandish art is undeniable. Furthermore, Schongauer clearly built upon the achievements of earlier German engravers, particularly the anonymous artist known as Master E. S., whose technical advancements in printmaking provided a foundation upon which Schongauer would build his own revolutionary approach.

The Ascent of Engraving as Fine Art

While Schongauer also worked as a painter, his most profound and lasting contribution lies in the realm of copperplate engraving. Before him, engraving was often considered a minor art, frequently associated with decorative metalwork or the production of playing cards. Schongauer, however, elevated the medium to an unprecedented level of artistic sophistication and expressive potential. He treated the engraved print not merely as a reproductive tool but as an independent work of art capable of conveying complex narratives and profound emotions.

His technical mastery was unparalleled in his time. Schongauer wielded the burin—the sharp steel tool used to incise lines into the copper plate—with extraordinary control and sensitivity. He developed a systematic and highly refined vocabulary of lines, employing delicate hatching (parallel lines) and intricate cross-hatching (intersecting lines) to model form, suggest texture, and create subtle gradations of light and shadow. This allowed him to achieve a richness of tone and a sense of volume previously unseen in engraving.

His prints are characterized by their clarity of line, balanced compositions, and meticulous attention to detail. He signed many of his plates with his distinctive monogram, "M†S," effectively branding his work and asserting his authorship in a way that was relatively new for printmakers. This practice, combined with the high quality and artistic ambition of his prints, helped establish engraving as a major art form, respected alongside painting and sculpture. The reproducibility of prints also meant his work could circulate widely, disseminating his style and technical innovations far beyond the Upper Rhine.

Masterpieces in Metal: Key Engravings

Schongauer produced approximately 116 engravings, almost exclusively on religious themes, which resonated deeply with the pious sentiments of the late medieval period. Among his most celebrated works is The Temptation of Saint Anthony. This print depicts the beleaguered saint being tormented in mid-air by a grotesque host of demonic creatures. The work is a tour-de-force of imaginative power and technical skill, showcasing Schongauer's ability to render fantastic forms with convincing detail and dynamic energy. Its fame was such that even the young Michelangelo is known to have studied and copied it in a painted version, attesting to its impact across the Alps.

Another significant body of work is his Passion Series, a set of twelve engravings depicting the suffering and death of Christ. Plates such as Christ Carrying the Cross and Christ on the Cross demonstrate Schongauer's ability to convey intense emotion through expressive figures and carefully orchestrated compositions. The series as a whole presents a moving narrative cycle, marked by both dramatic intensity and moments of tender pathos. These prints served as powerful devotional images for contemporary viewers.

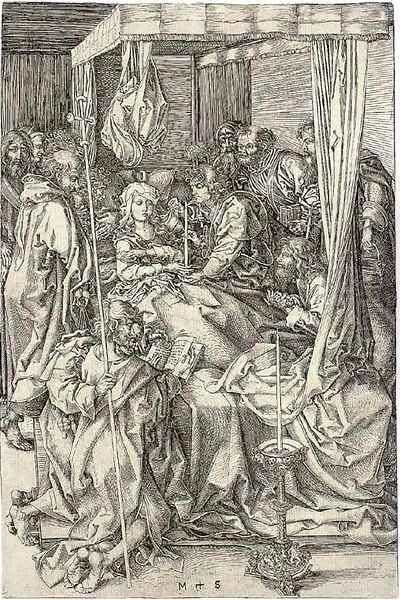

The Death of the Virgin is another masterpiece, admired for its complex yet harmonious composition, the variety of emotional responses depicted in the gathered apostles, and the exquisite rendering of textures and drapery. Schongauer masterfully uses light and shadow to focus attention on the central figures and create a solemn, reverent atmosphere. Other notable engravings include depictions from the Life of the Virgin, such as the Annunciation and the Nativity, as well as powerful single figures of apostles and saints like Saint James the Greater battling demons or the imposing Saint Michael weighing souls.

Schongauer the Painter: Color and Form

Although fewer paintings by Schongauer survive compared to his engravings, they confirm his status as a leading master in this medium as well. His most famous painting is the Madonna in the Rose Garden, created in 1473 and still housed in its original location, the Church of Saint Martin in Colmar (though now protected in a different part of the church). This luminous panel painting depicts the Virgin Mary and Christ Child seated in an enclosed garden, surrounded by blooming roses and birds, symbols of Mary's purity and paradise.

The Madonna in the Rose Garden exemplifies Schongauer's painting style, which closely aligns with the Netherlandish tradition. The work is characterized by its vibrant, jewel-like colors, meticulous rendering of details (from the delicate flower petals to the textures of the fabrics), and the serene, idealized beauty of the figures. The influence of Rogier van der Weyden and perhaps Dieric Bouts is evident in the gentle piety and refined execution. The painting radiates a sense of calm devotion and exquisite craftsmanship.

Other documented painting projects include fragments of the large Orlier Altarpiece, also preserved in Colmar's Unterlinden Museum (famous for housing Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece). These fragments further demonstrate his skill in handling complex compositions and rich color palettes on a larger scale. His final major undertaking was likely the series of monumental frescoes depicting the Last Judgment on the west wall of the Minster (cathedral) in Breisach am Rhein, a town not far from Colmar.

The Breisach Frescoes: A Final Monument

The Last Judgment frescoes in Breisach represent Schongauer's most ambitious project in painting. Though damaged over time and subject to later restorations, these large-scale wall paintings reveal his ability to manage vast compositions with numerous figures. The depiction of Christ enthroned as judge, the weighing of souls by Saint Michael, the separation of the blessed and the damned, all unfold across the imposing wall space. The surviving sections show Schongauer adapting his refined style to the demands of monumental fresco painting.

Work on the Breisach frescoes was likely ongoing when Schongauer died. Historical records indicate his death occurred in Breisach on February 2, 1491. It is widely believed he passed away while still engaged in this significant commission, leaving the work potentially unfinished or completed by assistants. These frescoes, despite their condition, stand as a testament to his versatility and his stature as an artist entrusted with major public commissions.

Artistic Style: Gothic Grace and Renaissance Realism

Martin Schongauer's art occupies a fascinating space between the Late Gothic and the Northern Renaissance. His style retains the elegance, intricate detail, and spiritual intensity characteristic of the Gothic tradition. Figures are often slender and graceful, draped in complex, beautifully rendered fabrics that break into sharp, angular folds. There is a lyrical quality to his line and a deep sincerity in the religious sentiment expressed.

At the same time, Schongauer embraced the growing interest in naturalism and realistic representation that marked the Renaissance. His attention to detail extends to the accurate depiction of plants, animals, and textures. He achieved a greater sense of volume and spatial depth in his engravings than his predecessors, employing his sophisticated shading techniques. His figures, while often idealized, possess a tangible presence and convey emotions with subtlety and conviction, particularly through their expressive faces and hands.

Compared to the slightly earlier Master E. S., Schongauer's work exhibits greater refinement, compositional harmony, and psychological depth. While contemporary German artists like Michael Pacher were exploring Renaissance perspective in sculpture and painting, Schongauer focused on perfecting the linear language of engraving and adapting the rich colorism of Flemish painting. His influence can be seen in the work of engravers who directly copied him, such as Israhel van Meckenem, but Schongauer's own prints always retain a superior delicacy and artistic integrity.

The Spread of Influence: A European Phenomenon

The invention of the printing press and the consequent ability to produce multiple impressions of engravings meant that Schongauer's work could travel far and wide. His prints circulated extensively throughout Europe, serving as models and sources of inspiration for artists in various regions. His impact was immediate and profound, particularly on the development of printmaking itself.

The most significant artistic heir to Schongauer was undoubtedly Albrecht Dürer. The younger artist deeply admired "Hübsch Martin" (Handsome Martin), as Schongauer was affectionately known. Dürer embarked on his journeyman travels in 1490, intending to meet Schongauer in Colmar. He arrived in 1492, only to find that the master had died the previous year. Dürer was welcomed by Schongauer's brothers (also artists and goldsmiths) and likely gained access to remaining drawings and plates. Dürer's early work clearly shows him studying and even copying Schongauer's engravings, absorbing the older master's technical finesse and compositional strategies before forging his own revolutionary path. Schongauer provided the essential foundation upon which Dürer built his own towering achievements in printmaking.

Schongauer's influence extended well beyond Germany. His prints were highly sought after in Italy. As mentioned, Michelangelo copied The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Artists like Raphael may have known his work, and painters such as Ghirlandaio and Perugino likely drew inspiration from the compositions and figural types found in Schongauer's widely circulated prints. While Italian artists like Andrea Mantegna were simultaneously developing engraving in Italy with a harder, more sculptural line, Schongauer's Northern style offered a different model of linear refinement and tonal richness.

In the Netherlands, artists like Lucas van Leyden, a major printmaker of the next generation, clearly learned from Schongauer's example. His prints also traveled to Spain, influencing Spanish painters and engravers. While specific collaborations mentioned in some sources (like with Martín Bernat) require careful consideration, the general presence and impact of Schongauer's models in Spanish art of the period is acknowledged. His work thus played a crucial role in the cross-cultural artistic exchanges of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Other German artists like Lucas Cranach the Elder and Hans Baldung Grien also show familiarity with his work.

Enduring Legacy and Unanswered Questions

Martin Schongauer's legacy is multifaceted. He was instrumental in transforming copperplate engraving from a craft into a major art form. His technical innovations provided a sophisticated linear language for modeling form and creating tonal effects that remained influential for centuries. His prints set a high standard for quality and artistic ambition, demonstrating the medium's capacity for complex narratives and profound expression. His work perfectly encapsulates the transition from the Late Gothic world to the Northern Renaissance.

Despite his fame and influence, some aspects of Schongauer's life and work remain subjects of scholarly discussion. The exact dates of his birth and the specifics of his early training continue to be debated. The full extent of his painted oeuvre is unknown, as many works have likely been lost over time. The precise iconographic meanings of some of his more complex prints, like the fantastical Temptation of Saint Anthony, still invite interpretation.

Today, Schongauer's engravings are treasured highlights in the print rooms of major museums worldwide, including the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. His paintings, though fewer in number, are recognized as key works of the period. He remains a pivotal figure, admired for his technical brilliance, his sensitive artistry, and his profound impact on the course of European art history, particularly through his elevation of the art of engraving. His elegant line and deep spirituality continue to captivate viewers more than five centuries after his death.