The Italian Renaissance, a period of extraordinary cultural rebirth, witnessed a profound transformation in the visual arts. Artists moved away from the stylized conventions of the Gothic era towards a new naturalism, a deeper understanding of human anatomy, and the groundbreaking application of scientific principles to create illusionistic space. Among the vanguard of this artistic revolution, one young painter stands out for his meteoric rise and enduring impact: Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, known to posterity as Masaccio. Active for a mere decade, from roughly 1422 until his untimely death in 1428 at the age of 26 or 27, Masaccio laid a foundation upon which generations of artists, including giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, would build. His work signaled a definitive break with the past and heralded the dawn of a new age in painting.

The Florentine Crucible: Early Life and Influences

Born in 1401 in San Giovanni Valdarno, a town in the territory of Florence, Masaccio's early life and artistic training remain somewhat obscure. The Florence of the early 15th century, however, was a vibrant hub of artistic and intellectual innovation. The legacy of Giotto di Bondone, who a century earlier had already taken significant steps towards naturalism and emotional expression in painting, still resonated powerfully. Giotto’s frescoes in the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels in Santa Croce, Florence, and the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, with their weighty figures and dramatic narratives, provided a crucial precedent for Masaccio’s own explorations.

While no definitive records pinpoint Masaccio’s master, it is clear he was deeply immersed in the artistic currents of his time. He would have been acutely aware of the revolutionary developments in sculpture led by Donatello and in architecture by Filippo Brunelleschi. Donatello’s statues, such as his St. Mark for Orsanmichele, exhibited a new psychological intensity and realistic anatomical rendering that undoubtedly influenced Masaccio’s approach to the human figure. Brunelleschi, famed for his design of the dome of Florence Cathedral, was also pioneering the systematic use of linear perspective, a tool that Masaccio would masterfully adapt for painting. It is likely that Masaccio associated with these leading artists, absorbing their innovative ideas and translating them into his own medium. He registered with the Florentine painters' guild, the Arte de' Medici e Speziali, in 1422, marking his official entry as an independent master.

Early Works: The Emergence of a Powerful Vision

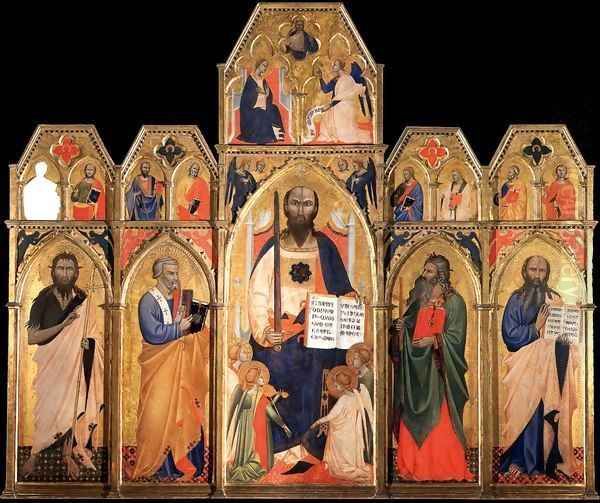

One of Masaccio’s earliest documented works is the San Giovenale Triptych, dated 1422, now housed in the Church of San Pietro e Paolo in Cascia di Reggello. Even in this early piece, Masaccio’s distinct artistic personality begins to emerge. The central panel depicts the Virgin and Child enthroned, flanked by angels, with Saints Bartholomew and Blaise on the left wing, and Saints Juvenal and Anthony Abbot on the right. While still showing some adherence to traditional forms, the figures possess a solidity and a nascent understanding of perspective that set them apart. The Christ Child, for instance, is rendered with a naturalism and chubbiness that contrasts with the more ethereal depictions common in the International Gothic style prevalent at the time, a style exemplified by artists like Gentile da Fabriano.

The influence of Donatello is palpable in the weighty presence of the saints and the Virgin. The attempt to create a believable, albeit shallow, space for the figures, particularly in the depiction of the throne, hints at Masaccio’s burgeoning interest in perspective. This work, though perhaps not as revolutionary as his later frescoes, clearly signals the arrival of a formidable new talent.

The Brancacci Chapel: A Landmark of Renaissance Fresco Painting

Masaccio’s most celebrated and influential works are the frescoes he painted in the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. Commissioned by the wealthy silk merchant Felice Brancacci around 1424, the chapel's decoration was a collaborative effort between Masaccio and the slightly older, more established artist Masolino da Panicale. The frescoes depict scenes from the life of Saint Peter, the patron saint of the Brancacci family.

The collaboration with Masolino provides a fascinating study in contrasting artistic visions. Masolino, while a skilled painter, largely adhered to the more graceful and decorative International Gothic style. Masaccio, on the other hand, brought a new monumentality, psychological depth, and spatial realism to his scenes. This contrast is evident when comparing Masolino’s Temptation of Adam and Eve with Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden on the chapel’s entrance arch. Masolino’s figures are elegant and idealized, standing in a somewhat timeless, decorative landscape. Masaccio’s Adam and Eve, however, are figures of raw, palpable anguish. Their bodies are powerfully modeled, their faces contorted in grief and shame as an angel expels them from Paradise. The raw emotional power and anatomical realism of Masaccio’s Expulsion were unprecedented.

Perhaps the most famous fresco in the Brancacci Chapel is Masaccio’s The Tribute Money. This large narrative scene depicts the episode from the Gospel of Matthew where Christ instructs Peter to find a coin in the mouth of a fish to pay the temple tax. Masaccio masterfully organizes the complex narrative into a unified composition. Christ and his apostles are arranged in a semi-circle, their figures solid and imposing, imbued with a quiet dignity. The use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) models their forms, giving them a three-dimensional presence. The landscape, though somewhat stark, recedes convincingly into the distance, an early example of atmospheric perspective. Linear perspective is employed in the architecture on the right. The figures are not merely participants in a story; they are individuals with distinct psychological states, conveyed through their expressions and gestures. The gravity and realism of this scene marked a significant departure from earlier narrative painting.

Other scenes attributed to Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel, such as St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow and The Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias, further demonstrate his command of perspective, his ability to render figures with monumental weight, and his focus on human drama. Unfortunately, Masaccio left the Brancacci Chapel project unfinished when he departed for Rome in 1428. The frescoes were eventually completed decades later by Filippino Lippi, who respectfully adapted his style to harmonize with the work of his predecessors. The Brancacci Chapel became a veritable school for later Renaissance artists, with figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo reportedly studying and sketching Masaccio’s powerful figures.

The Holy Trinity: A Masterpiece of Illusionism

Concurrent with his work in the Brancacci Chapel, Masaccio created another groundbreaking fresco, The Holy Trinity, in the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (circa 1425-1427). This work is widely regarded as one of the first, and most perfect, demonstrations of systematic linear perspective in painting. The fresco depicts the Trinity – God the Father supporting the crucified Christ, with the Holy Spirit as a dove between them – within a coffered barrel-vaulted chapel. Flanking the cross are the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist. Outside this sacred space, kneeling in prayer, are the two donor figures, likely members of the Lenzi family. Below the main scene, a tomb contains a skeleton with the memento mori inscription: "I was once what you are, and what I am you also will be."

The illusion of a deep, recessed chapel is astonishingly convincing. Masaccio, almost certainly guided by Brunelleschi’s principles, constructed the space with a single vanishing point located at the eye level of a viewer standing in the nave. The architecture is rendered with such precision that it appears to be a real extension of the church’s physical space. The figures within this illusionistic space are characterized by Masaccio’s typical solidity and emotional gravity. The Virgin Mary, depicted as an older woman, gestures towards Christ, not with overt emotion, but with a solemn resignation that invites the viewer to contemplate the sacrifice. The Holy Trinity is a profound theological statement and a technical tour-de-force, demonstrating how artistic innovation could serve powerful spiritual ends. It set a new standard for illusionistic painting and profoundly influenced artists like Andrea Mantegna and Piero della Francesca, who further explored the possibilities of perspective.

The Pisa Altarpiece and Other Panel Paintings

While best known for his frescoes, Masaccio also produced significant panel paintings. In 1426, he was commissioned to paint a large polyptych for the Carmelite Church in Pisa. This altarpiece, known as the Pisa Altarpiece, was later dismembered, and its panels are now scattered among various museums worldwide. The central panel, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels, now in the National Gallery, London, showcases Masaccio’s ability to translate his monumental style to a smaller scale. The Virgin is a solemn, powerful figure, and the Christ Child, eating grapes (a symbol of the Eucharist), is depicted with a remarkable naturalism. The throne incorporates classical architectural elements and demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of perspective.

Other surviving panels from the Pisa Altarpiece include the Crucifixion (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples), which conveys intense pathos, particularly in the figure of Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross. Panels depicting various saints, such as Saint Paul (Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa) and Saint Andrew (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), further illustrate Masaccio's ability to imbue individual figures with character and presence. The predella panels, including an Adoration of the Magi (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), show his skill in narrative composition on a smaller scale.

Another notable panel painting is the Madonna of Humility (or Madonna Casini), now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (though some scholars place a version in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.). This small devotional work depicts the Virgin seated on the ground with the Christ Child, a theme popular for private devotion. Masaccio invests this intimate scene with a tender humanity and a sense of volume that belies its small size.

Masaccio’s Revolutionary Techniques

Masaccio’s enduring importance stems from his synthesis and masterful application of several key artistic innovations:

Linear Perspective: While Brunelleschi is credited with the mathematical formulation of linear perspective, Masaccio was among the very first painters to understand and systematically apply its principles to create a coherent, measurable, and illusionistic three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Works like The Holy Trinity and The Tribute Money are prime examples of this.

Chiaroscuro and Consistent Light Source: Masaccio abandoned the flat, even lighting common in Gothic painting. Instead, he used strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model his figures, giving them a sense of volume and solidity. Crucially, he often employed a single, consistent light source within his compositions, casting realistic shadows and further enhancing the illusion of three-dimensionality, as seen in The Tribute Money where shadows are cast consistently as if from a light source to the right.

Naturalism and Realism: Masaccio’s figures are not idealized, ethereal beings; they are substantial, weighty individuals with a tangible physical presence. He studied human anatomy (perhaps through observation of Donatello's sculptures) to render bodies with greater accuracy. His depiction of emotions, as seen in the Expulsion or the apostles in The Tribute Money, is direct and psychologically convincing, moving beyond mere symbolic representation.

Monumentality and Simplicity: Masaccio’s compositions are characterized by a sense of grandeur and clarity. He eschewed fussy details and decorative embellishments, focusing instead on the essential elements of the narrative and the monumental presence of his figures. This simplicity and directness contribute to the power and impact of his work. Artists like Fra Angelico, though working with a more lyrical sensibility, also absorbed lessons from Masaccio's spatial clarity and figure modeling.

The "Unknown Master" Clarification

It is important to address a potential point of confusion. The term "Italian Unknown Masters" refers to artists from various periods, including the Renaissance, whose identities have been lost to history. Their works might be unsigned, or records of their authorship may not have survived. Art historians sometimes group these works under provisional names based on style, location, or a distinctive subject, such as the "Maestro delle Storie del Pane."

Masaccio, however, is emphatically not an "Unknown Master." His identity, key works, and profound impact are well-documented, primarily through the writings of Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects" (1550, revised 1568). Vasari recognized Masaccio's pivotal role in the development of Renaissance art, praising his mastery of perspective and naturalism. While some details of Masaccio's life remain obscure, his major artistic achievements are firmly established in the art historical canon.

Untimely Death and Enduring Legacy

In 1428, Masaccio traveled to Rome, possibly to work on a commission with Masolino at San Clemente or on a polyptych for Santa Maria Maggiore. Tragically, he died there later that year, under circumstances that remain unclear. Vasari recounts a rumor that he was poisoned, but this has never been substantiated. His death at such a young age cut short a career of extraordinary promise.

Despite its brevity, Masaccio’s career was transformative. He effectively bridged the gap between the late Gothic style and the Early Renaissance. His innovations in perspective, light, and naturalism provided a new visual language that would be adopted and developed by subsequent generations of artists. The Brancacci Chapel, in particular, became a pilgrimage site for artists eager to learn from his example.

The list of artists influenced by Masaccio is a veritable who's who of the Renaissance. Fra Filippo Lippi, who may have been a young friar at Santa Maria del Carmine during Masaccio's work there, clearly absorbed his lessons in solidity and humanism. Andrea del Castagno and Paolo Uccello further explored the depiction of powerful figures and complex perspective. Piero della Francesca, renowned for his own mastery of perspective and serene, monumental figures, owed a significant debt to Masaccio. Later, High Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael all studied Masaccio’s frescoes, recognizing in them the foundations of their own artistic achievements. Leonardo's use of chiaroscuro and psychological depth, Michelangelo's powerful, anatomically precise figures, and Raphael's harmonious compositions all bear the imprint of Masaccio's pioneering vision. Even beyond Italy, artists like Rogier van der Weyden in the North, while developing a distinct tradition, shared a similar concern for realism and emotional depth that was becoming a hallmark of the new age.

Unresolved Questions and the Enigma of Masaccio

Despite his fame, aspects of Masaccio's life and work remain subjects of scholarly debate. The precise nature of his early training is unknown. The rapid and seemingly sudden maturation of his style, particularly his leap beyond his collaborator Masolino, is remarkable. How did he so quickly absorb and synthesize the complex ideas of perspective and naturalism? The exact circumstances of his death in Rome also remain an enigma. Furthermore, some of his works may have been lost, leaving gaps in our understanding of his complete oeuvre. These unanswered questions contribute to the enduring fascination with this revolutionary artist.

Conclusion: A Cornerstone of Western Art

Masaccio was more than just a talented painter; he was a visionary who fundamentally changed the course of Western art. In a career spanning barely a decade, he mastered and synthesized the key elements that would define Renaissance painting: scientific perspective, realistic modeling of form through light and shadow, anatomical accuracy, and profound psychological insight. His work provided a powerful new model for depicting the human figure and a believable, illusionistic space. By rejecting the decorative conventions of the International Gothic and embracing a more austere, monumental, and human-centered naturalism, Masaccio laid the groundwork for centuries of artistic development. His frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel and The Holy Trinity in Santa Maria Novella remain testaments to his genius and stand as enduring landmarks in the history of art, securing his place as one of the true founders of Renaissance painting.