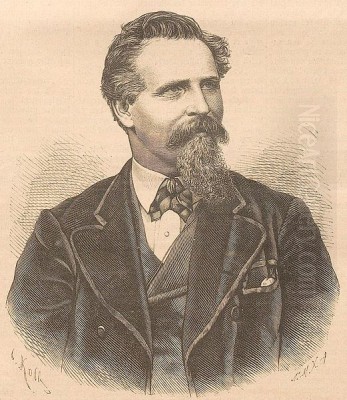

Mathias Schmid (1835–1923) stands as a significant figure in 19th and early 20th-century Austrian art, particularly renowned for his evocative genre scenes and poignant social critiques. Born in the heart of the Tyrolean Alps, his work is deeply imbued with the spirit, traditions, and often the hardships of its people. Schmid's artistic journey took him from humble beginnings to the esteemed academies of Vienna and Munich, yet he remained steadfastly connected to his Tyrolean roots, which provided the primary wellspring of his inspiration. His paintings offer a window into a world of rural customs, religious practices, and the underlying social tensions of his era, rendered with a keen observational eye and a distinctive, often critical, perspective.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Mathias Schmid was born in See near Ischgl, in the Paznaun valley of Tyrol, Austria, on November 14, 1835. His early life in this Alpine region would profoundly shape his artistic vision. The rugged landscapes, the distinct local culture, and the everyday lives of the Tyrolean people became recurring themes in his later work. Like many artists of his generation who hailed from less privileged backgrounds, Schmid's path to a formal artistic education was not immediate.

His initial foray into the world of art began with an apprenticeship. In 1853, at the age of eighteen, Schmid moved to Munich, a burgeoning artistic hub in the German-speaking world. There, he reportedly worked in a gilder's shop, a trade that, while practical, would have exposed him to decorative arts and perhaps fueled his desire for more profound artistic expression. This period in Munich was formative, allowing him to immerse himself in a vibrant artistic environment.

After approximately three years in Munich, gaining foundational skills and likely saving what he could, Schmid made his way to Vienna, the imperial capital and another major center for the arts. In 1856, he enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. The Vienna Academy, with its strong emphasis on classical training and historical painting, would have provided him with a rigorous academic grounding. However, his initial focus was not on the genre scenes for which he would become famous.

The Munich Influence and a Shift in Direction

Schmid's studies in Vienna laid a technical foundation, but it was his return to Munich and his subsequent engagement with the artistic currents there that truly defined his mature style. In 1869, a pivotal year for his career, Schmid moved back to Munich and joined the school of Karl von Piloty (1826–1886). Piloty was one of the most influential history painters in Germany at the time, heading a prominent school at the Munich Academy. His large-scale, dramatic historical canvases were celebrated for their realism, meticulous detail, and theatrical compositions.

Under Piloty, Schmid would have been immersed in an environment that valued historical accuracy and narrative power. Many of Piloty's students went on to become leading artists, including Franz von Lenbach, Franz Defregger, Hans Makart, and Wilhelm Leibl. While Schmid absorbed the technical prowess and narrative focus of the Piloty school, his thematic interests began to diverge from grand historical epics towards more intimate, everyday scenes.

A significant influence during this period was fellow Tyrolean artist Franz Defregger (1835–1921). Defregger, also a student of Piloty, was already gaining acclaim for his depictions of Tyrolean peasant life and historical events from the Tyrolean rebellions. It is said that Defregger encouraged Schmid to draw inspiration from their shared Tyrolean heritage. This guidance proved crucial, leading Schmid to increasingly focus on genre painting, capturing the folk life, customs, and social dynamics of his native region. This shift allowed him to find his unique artistic voice.

Tyrolean Life: Celebration and Critique

The Tyrol, with its distinct cultural identity, strong Catholic traditions, and often isolated communities, provided Schmid with a rich tapestry of subjects. His genre paintings from this period are characterized by their detailed observation of local costumes, interiors, and social interactions. He depicted weddings, festivals, domestic scenes, and moments of quiet contemplation, often with a warmth and empathy that resonated with a public increasingly interested in regional cultures.

However, Schmid's portrayal of Tyrolean life was not merely idyllic or romanticized. A critical undercurrent runs through many of his most compelling works. He did not shy away from depicting the harsher realities, the social inequalities, and the sometimes-stifling influence of clerical authority in rural communities. This critical edge distinguished him from many other genre painters of the time.

Works such as "The Beggar Monks" (or "Bettelmönche"), "The Carters" (or "Die Fuhrleute"), "The Informer in the Confessional" (or "Der Verräter im Beichtstuhl"), and "The Merchant's God" (or "Der Gott des Kaufmanns") exemplify this critical stance. These paintings often subtly or overtly questioned established power structures, particularly within the Church, and highlighted the plight of the common people. His willingness to tackle such sensitive subjects demonstrated considerable courage and a deep engagement with the social issues of his day.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Several of Mathias Schmid's paintings have achieved lasting recognition, both for their artistic merit and their thematic content.

One of his most famous and historically significant works is "The Expulsion of the Zillertal Protestants" (Die Ausweisung der Zillertaler Protestanten). This painting depicts a poignant historical event from 1837 when several hundred Protestant families were forced to leave their homes in the Zillertal valley in Tyrol due to religious intolerance. Schmid’s portrayal, likely painted much later in his career when such themes of religious persecution resonated with his own experiences and beliefs, captures the sorrow and injustice of the event. It showcases his ability to combine historical narrative with deep human emotion, a hallmark of the Piloty school, but applied to a subject of profound regional and social significance.

Another well-known piece is "Die Feuerbeschau" (The Fire Inspection). This work, housed in the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich, is a prime example of his genre painting. Measuring 99 x 128 cm, it likely depicts a scene of rural life, perhaps an official inspection related to fire safety, a common occurrence in tightly packed village structures. Such scenes allowed Schmid to explore community dynamics and the interplay of different characters within a specific social context.

His painting "The Smugglers" (Die Schmuggler) touches upon another aspect of life in the mountainous border regions, hinting at the clandestine activities and the spirit of defiance that could arise from economic hardship or restrictive trade policies. Similarly, "The Poacher" (Der Wilderer) delves into the conflicts between traditional hunting rights, survival, and the laws imposed by landowners or the state.

Works like "The Blessing of the Alpine Pastures" (Almsegen) show a more traditional aspect of Tyrolean life, depicting religious ceremonies integral to the agricultural calendar and the deep faith of the rural populace. Yet, even in such scenes, Schmid’s keen observation of human character is evident.

His critical paintings, such as "The Priest as a Marital Devil" (Der Pfarrer als Ehetufel), directly addressed the perceived interference of the clergy in personal lives, a theme that would have been controversial but resonated with growing anti-clerical sentiments in some quarters. "Begging Jews" (Betteljuden), painted around 1870, is another example of his engagement with social themes, though its interpretation can be complex within the context of 19th-century depictions of Jewish communities.

Artistic Style and Technique

Mathias Schmid's style evolved from his academic training but was refined through his focus on genre and historical scenes. He is often associated with the Realism movement, particularly the Munich School variant, which emphasized accurate depiction, strong narrative content, and often a touch of anecdotal charm or social commentary.

His compositions are typically well-structured, guiding the viewer's eye through the narrative. He paid close attention to detail, whether in the rendering of traditional Tyrolean costumes, the textures of rustic interiors, or the expressive faces of his figures. His figures are not idealized; they are portrayed with a sense of individuality and authenticity, often capturing a range of emotions from joy and piety to sorrow and quiet defiance.

Schmid's use of color was generally rich and naturalistic, though sometimes subdued to match the mood of the scene. He was adept at using light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create atmosphere and highlight key elements within his paintings. His brushwork, while detailed, often retained a certain painterly quality, avoiding the overly polished finish of some academic painters. This allowed for a sense of immediacy and vitality in his work. The "delicate and soft colors" and "elegant forms" mentioned in some descriptions point to a refinement that balanced his realistic depictions.

Religious Convictions and the Old Catholic Church

A significant aspect of Mathias Schmid's life and work was his involvement with the Old Catholic Church. The Old Catholic movement emerged in the 1870s as a response by some German-speaking Catholics to the proclamation of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council (1869-1870). Those who rejected this dogma formed independent communities that sought to adhere to what they considered the older, more authentic traditions of the Catholic Church.

Schmid became a founding member and an active participant in the Old Catholic community in Munich. This religious affiliation is highly relevant to understanding his art, particularly his critical depictions of the mainstream Roman Catholic clergy and certain church practices. His paintings often reflect a desire for a more direct, less hierarchical form of faith, and a critique of what he perceived as abuses of power or hypocrisy within the established Church. His personal convictions likely fueled his courage to tackle anti-clerical themes, which, while finding an audience, also brought him into conflict with conservative elements, especially in his native Tyrol. It is reported that due to his liberal views and critical art, he faced persecution from clerical circles in Tyrol, prompting his more permanent settlement in Munich, a more liberal environment.

Recognition, Later Years, and Legacy

Mathias Schmid achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His paintings were exhibited in Munich, Vienna, and other European cities, and they were popular with both critics and the public who appreciated his skillful storytelling and his authentic portrayal of Tyrolean life. His work resonated with the growing interest in regional identities and folk cultures that was characteristic of the 19th century.

In 1887, he was appointed an honorary professor at the Royal Academy of Arts in Munich, a testament to his standing in the artistic community, although it's noted he never actually taught in this capacity. He also received honors such as the Knight's Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph I, awarded by the Austrian Emperor, indicating official recognition from his home country.

Schmid continued to paint into his later years, remaining based in Munich. He passed away in Munich on January 22, 1923, at the venerable age of 87.

His legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, he is considered one of Austria's most important genre painters of the 19th century. He successfully carved a niche for himself by focusing on Tyrolean subjects, bringing them to a wider European audience. His work provides invaluable historical documentation of Tyrolean customs, dress, and social life. Beyond mere documentation, his infusion of social critique into genre painting set him apart. He used his art not just to depict, but to comment and provoke thought.

The impact of Mathias Schmid is still felt, particularly in his native Tyrol. In Ischgl, the region of his birth, his contributions are celebrated. A private museum, the Mathias Schmid Museum, was established to showcase his works and preserve his memory. Furthermore, an art trail or "Mathias Schmid Kunstlehrpfad" in Ischgl allows visitors to engage with his art in the very landscape that inspired him. Streets named in his honor also testify to his enduring local importance. His paintings continue to be held in public collections, including the aforementioned Lenbachhaus in Munich, and appear in art auctions, demonstrating their continued appreciation.

Mathias Schmid in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Mathias Schmid's contribution, it's useful to see him in the context of the broader art world of his time. The 19th century was a period of immense artistic diversity, with Romanticism giving way to Realism, and later, Impressionism and various Post-Impressionist movements.

Schmid operated primarily within the sphere of Realism, particularly the Munich School, which, under Karl von Piloty, became a leading center for historical and genre painting. His contemporaries within this school included:

Franz Defregger (1835–1921): As mentioned, a close associate and fellow Tyrolean, whose depictions of peasant life and Tyrolean history often paralleled Schmid's, though perhaps with a generally less overtly critical tone.

Franz von Lenbach (1836–1904): Famous for his powerful portraits of prominent figures like Bismarck, Lenbach was a star of the Munich art scene.

Wilhelm Leibl (1844–1900): A leading figure of German Realism, known for his unsentimental depictions of peasant life, influenced by Gustave Courbet. Leibl and his circle (the "Leibl-Kreis") pushed for an even more direct and unvarnished realism.

Hans Makart (1840–1884): While also a Piloty student, Makart became the dominant figure in Viennese painting, known for his opulent, theatrical, and often allegorical compositions, quite different in spirit from Schmid's work.

In Austria, other notable painters of genre and everyday life included:

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793–1865): A leading figure of the Biedermeier period, known for his detailed and often sun-drenched depictions of Austrian landscapes and peasant life, preceding Schmid but setting a precedent for genre painting.

Peter Fendi (1796–1842): Another important Biedermeier artist, known for his intimate genre scenes, often with a sentimental or moralizing touch.

Friedrich von Amerling (1803–1887): Primarily a portrait painter, but his work reflects the high standards of Viennese painting during the period.

Internationally, the interest in peasant life and social realism was a broader trend:

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) in France was a towering figure of Realism, whose unidealized depictions of peasants and ordinary people, like "The Stone Breakers," had a profound impact across Europe.

Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), also in France, was renowned for his dignified portrayals of peasant laborers, such as "The Gleaners" and "The Angelus."

Adolph Menzel (1815–1905) in Germany was a master of historical scenes and depictions of everyday life, known for his meticulous observation and dynamic compositions.

Anton Mauve (1838–1888) and Jozef Israëls (1824–1911) were key figures of the Hague School in the Netherlands, often depicting rural life and fishing communities with a sombre realism.

Schmid's work, therefore, fits into this wider 19th-century fascination with the lives of ordinary people and the character of specific regions. His unique contribution lies in his specific focus on the Tyrol, combined with his critical engagement with social and religious issues, filtered through the lens of his personal convictions and his experiences within the Old Catholic Church. He was not simply a chronicler of folk life; he was an interpreter and, at times, a critic of the world he depicted.

Conclusion: An Enduring Tyrolean Voice

Mathias Schmid's artistic journey from the Paznaun valley to the academies of Vienna and Munich, and his subsequent dedication to portraying his native Tyrol, marks him as a distinctive voice in 19th-century art. He masterfully captured the visual richness of Tyrolean culture while simultaneously engaging with its underlying social and religious complexities. His ability to blend detailed realism with narrative depth, and to infuse his genre scenes with a critical perspective, ensures his continued relevance.

His legacy is preserved not only in museums and collections but also in the cultural memory of the Tyrol, where he is celebrated as an artist who gave profound expression to the spirit of his homeland. Through his paintings, Mathias Schmid offered a nuanced and enduring vision of Tyrolean life, securing his place as a significant Austrian painter whose work continues to resonate with audiences interested in the art, history, and social dynamics of his era. His commitment to his subjects, combined with his technical skill and critical insight, makes him a compelling figure for art historians and enthusiasts alike.