Maurice Mendjisky stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century European art. A Polish-born painter who found his artistic voice in the bustling ateliers and cafes of Paris, Mendjisky became an integral part of the famed École de Paris (School of Paris). His work, characterized by a sensitive engagement with his subjects and a nuanced understanding of contemporary artistic currents, offers a compelling window into a transformative era in art history. This exploration delves into his life, his distinctive style, the influences that shaped him, his notable works, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in 1890 in Łódź, a significant industrial city near Warsaw, Poland, Maurice Mendjisky (originally Mojżesz Mendżyski) emerged from a region rich in cultural and artistic ferment. His early years in Poland undoubtedly provided an initial cultural grounding, but like many aspiring artists of his generation, the magnetic pull of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, proved irresistible.

Around 1908, Mendjisky made the pivotal journey to Paris. This was a city electric with innovation, a melting pot where artists from across Europe and beyond converged to challenge conventions and forge new visual languages. He immersed himself in this dynamic environment, reportedly studying at what is referred to as the "First Art School of Paris," though specific details about his formal tutelage during this initial period remain somewhat general. What is clear is that his arrival coincided with a period of intense artistic experimentation, with Post-Impressionism still casting a long shadow and new movements like Fauvism and Cubism radically altering the artistic landscape.

The Parisian Crucible: Montparnasse and Artistic Development

Mendjisky quickly became associated with the École de Paris, a term that doesn't denote a specific institution but rather describes the diverse community of foreign-born artists who flocked to Paris, particularly to the Montparnasse district, between the World Wars. This group included luminaries such as Marc Chagall from Russia, Amedeo Modigliani from Italy, Chaïm Soutine from Lithuania, Tsuguharu Foujita from Japan, and Moïse Kisling, a fellow Pole. Spanish artists like Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris were also central figures, though often associated more directly with the development of Cubism.

Montparnasse was more than just a geographical location; it was an ecosystem of creativity, intellectual exchange, and bohemian life. Cafés like Le Dôme, La Rotonde, and Le Select buzzed with discussions, collaborations, and the forging of lifelong friendships and rivalries. Mendjisky was an active participant in this milieu. His integration into this vibrant scene was further cemented by his significant personal relationships, most notably with Alice Prin, famously known as Kiki de Montparnasse.

Kiki was a legendary figure – a model, nightclub singer, actress, and painter in her own right. She was the muse to many artists, including Man Ray, Foujita, and Soutine. Mendjisky and Kiki met around 1922, and their ensuing romantic relationship was intense. It is said that Mendjisky himself bestowed upon her the iconic nickname "Kiki." This connection placed Mendjisky at the very heart of Montparnasse's artistic and social life, facilitating interactions with a wide array of influential figures. Through Kiki, his connections with artists like Modigliani and Maurice Utrillo, for whom Kiki also modeled, would have been natural.

Artistic Style and Influences: A Synthesis of Traditions

Maurice Mendjisky's artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of various influences, reflecting his deep engagement with the artistic currents of his time while retaining a distinct personal sensibility. He was not a dogmatic follower of any single movement but rather a thoughtful synthesizer, drawing inspiration from diverse sources to create a unique visual language.

The overarching influence of the École de Paris is evident in his work, particularly its emphasis on individual expression and a certain lyrical quality. He clearly absorbed lessons from the Post-Impressionists, particularly Paul Cézanne. Cézanne's revolutionary approach to structure, his way of building form through color, and his emphasis on the underlying geometry of nature left an indelible mark on Mendjisky. This can be seen in the solidity and thoughtful construction of his compositions, especially in his landscapes and still lifes.

Mendjisky also showed an affinity for the expressive power of color, a characteristic that links him to Fauvism, the movement championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, known for its bold, non-naturalistic use of color. While Mendjisky's palette was often more subdued and nuanced than that of the core Fauves, the emotional resonance of color was clearly important to him.

Elements of Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and Georges Braque, can also be discerned in his approach to form. The Cubist deconstruction and reconstruction of objects, the exploration of multiple viewpoints, and the emphasis on geometric underpinnings likely informed Mendjisky's way of seeing and representing the world, lending a modern sensibility to his work without him becoming a strict adherent to Cubist dogma.

Furthermore, Divisionism, an offshoot of Neo-Impressionism developed by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, played a role in shaping his technique. Divisionism, often referred to as Pointillism in its most famous manifestation, involved applying small, distinct dots or strokes of pure color to the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to optically mix them. Mendjisky adapted this technique, not always in its purest form, but the principle of using broken color to achieve luminosity and vibrancy is apparent in many of his paintings. This technique allowed for a "decomposition and recomposition of the picture," creating a dynamic visual experience.

The influence of Chaïm Soutine, another prominent member of the École de Paris, is also notable, particularly in the expressive intensity and sometimes turbulent energy found in some of Mendjisky's works. Soutine's visceral, emotionally charged brushwork and distorted forms resonated with many artists seeking to move beyond mere representation.

Despite these diverse influences, Mendjisky's art is often characterized by a certain gentleness and warmth. His brushwork could be both robust and delicate, and he possessed a remarkable ability to convey emotion with subtlety. His color harmonies are often sophisticated, employing soft tones that create a poetic atmosphere. This is particularly evident in his depictions of children, where a profound sense of tenderness and empathy shines through.

Key Themes and Subjects

Maurice Mendjisky explored a range of subjects throughout his career, each approached with his characteristic blend of modernist sensibility and emotional depth.

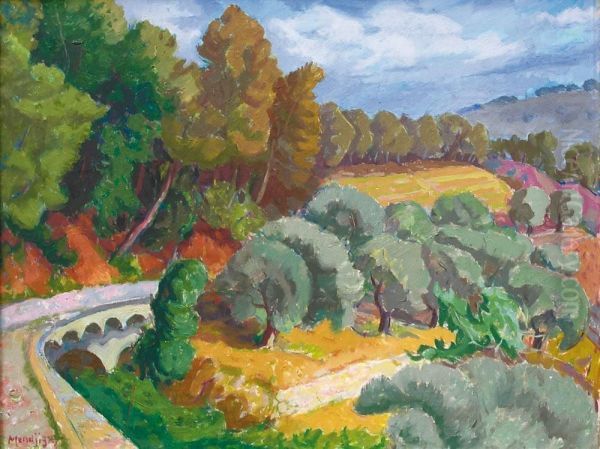

Landscapes were a significant part of his oeuvre. He was drawn to the natural beauty of France, particularly regions like Provence. His landscapes are not mere topographical records but rather interpretations imbued with personal feeling and a keen sense of light and atmosphere. He sought to capture the essence of a place, often employing the structural lessons of Cézanne and the coloristic vibrancy of Divisionism.

Portraits also occupied an important place in his work. His most famous portrait is undoubtedly that of Alice (Kiki de Montparnasse), but he likely painted other figures within his circle. His portraits aimed to capture not just a physical likeness but also the inner life and character of the sitter. The 1919 portrait of Alice is described as a work of simple composition and soft light, a model of traditional portraiture infused with a modern touch.

His depictions of children, as mentioned earlier, are particularly noteworthy for their sensitivity and warmth. These works reveal a compassionate side to the artist, an ability to connect with the innocence and vulnerability of youth.

A unique and historically significant aspect of his work involves the thirty-four plans he created for the Warsaw Ghetto. This undertaking speaks to a deep engagement with his heritage and a desire to bear witness or contribute in some way to the memory of this tragic chapter of history. These plans, likely architectural or schematic in nature, demonstrate a different facet of his artistic skill, moving beyond easel painting into the realm of spatial representation and historical documentation. This pursuit of "authenticity and harmony" is noted as a driving force in these works.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might offer a fuller picture, several works by Maurice Mendjisky are frequently cited and help to illustrate his artistic concerns and stylistic evolution.

_Paysage de Provence_ (Landscape in Provence), 1946: Provence, with its unique light and rugged beauty, has captivated artists for generations, from Vincent van Gogh to Paul Cézanne and beyond. Mendjisky's 1946 depiction of this iconic region would likely reflect his mature style, blending Cézannian structure with a more lyrical use of color, perhaps influenced by Divisionist techniques to capture the brilliant Mediterranean light. The specific content isn't detailed in the provided information, but one can imagine sun-drenched fields, olive groves, or the characteristic architecture of the region rendered with his signature sensitivity.

_Baie de Saint Tropez_ (Bay of Saint Tropez), 1938: This oil painting, measuring 33 x 41 cm, captures another famed location on the French Riviera. Saint Tropez, even before its mid-century heyday, was a magnet for artists. Signac had a home there and it became a key site for Neo-Impressionist painters. Mendjisky's 1938 rendition would likely showcase his ability to convey the shimmering light and vibrant atmosphere of the Mediterranean coast, possibly employing broken brushwork and a bright palette.

_Bord du Loing_ (Banks of the Loing), 1939: An oil painting measuring 50 x 65.5 cm, this work depicts the Loing River, a tributary of the Seine that flows through a region popular with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters like Alfred Sisley. This subject suggests Mendjisky's continued engagement with the French landscape tradition, interpreting it through his own modernist lens. One might expect a focus on the reflective qualities of water and the lushness of the riverbanks.

_La Colombe d'or à Saint Paul de Vence_ (The Golden Dove in Saint Paul de Vence), 1922: This work, measuring 65 x 80.5 cm, refers to the famous inn and artists' haven in the South of France. La Colombe d'Or was frequented by many prominent artists, including Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Léger, and Calder, who often paid for their stays with artworks. Mendjisky's painting from 1922, the year he reportedly met Kiki, could capture the ambiance of this legendary establishment or the picturesque village of Saint Paul de Vence itself.

_Alice_, 1919: This portrait of Alice Prin (Kiki de Montparnasse) is highlighted as a significant early work. Described as a depiction of her youth, rendered with simple composition and soft light, it is considered a model of traditional portraiture. This suggests that even as Mendjisky was absorbing modernist influences, he retained a strong grounding in classical representational skills. The painting would be invaluable for understanding his early style and his relationship with one of Montparnasse's most iconic figures.

The Warsaw Ghetto Plans: Though not paintings in the traditional sense, these 34 plans are a crucial part of his output. Created with a pursuit of "authenticity and harmony," they represent a deeply personal and historical project, showcasing his skills in draughtsmanship and spatial conceptualization, and reflecting a profound engagement with a tragic historical reality.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Maurice Mendjisky's work has been recognized through various exhibitions, ensuring his contribution to art history is acknowledged. A key institution in preserving and promoting his legacy is the Musée Mendjisky – Écoles de Paris, located in Paris. This museum, which reportedly opened on April 11, 2014, is dedicated to his work and that of other artists from the School of Paris.

A significant exhibition, "Rétrospective Mendjizy," was held at the Musée Mendjisky, opening around July 12, 2014. This retrospective featured nearly one hundred of his works, largely drawn from private and international collections. Crucially, it also included the thirty-four plans he created for the Warsaw Ghetto, highlighting this important aspect of his oeuvre. Such a comprehensive exhibition allows for a deeper understanding of his artistic journey and his pursuit of "authenticity and harmony."

Prior to this, it was noted that around one hundred unpublished works and designs by Mendjisky were exhibited in Paris before being moved to Warsaw. This indicates an ongoing effort to bring his lesser-known works to public attention in both his adopted artistic home and his country of origin. His works also appear in auctions, such as those held by OGER-BLANCHET, indicating a continued presence in the art market.

Collaborations and Publications

Beyond his painting, Mendjisky also engaged in illustration, collaborating with literary figures. A notable publication is the 1967 book Blanche ou l'oubli (White or Oblivion). This volume featured poems by the renowned Surrealist poet Paul Eluard and text by Vercors (the pseudonym of Jean Bruller, a writer and illustrator active in the French Resistance). Mendjisky contributed thirty-five illustrations to this book, showcasing his ability to visually interpret and complement literary works. Such collaborations were common among the Parisian avant-garde, fostering a rich interplay between visual art and literature.

Personal Life and the Montparnasse Milieu: The Kiki Connection

The story of Maurice Mendjisky is inextricably linked with that of Alice Prin, Kiki de Montparnasse. Their relationship, beginning around 1922, was a defining feature of his life during the height of Montparnasse's "années folles" (crazy years). Kiki was not just a passive muse; she was a vibrant artist herself, and her memoirs offer a vivid account of the era. Mendjisky's role in giving her the name "Kiki" is a testament to their intimacy and his influence on her persona.

Through Kiki, Mendjisky was deeply embedded in the social and artistic fabric of Montparnasse. This world was populated by a dazzling array of talents: Amedeo Modigliani, with his elongated, melancholic portraits; Chaïm Soutine, with his intensely expressive landscapes and portraits; Maurice Utrillo, known for his atmospheric Parisian street scenes. Others in this orbit included Man Ray, who famously photographed Kiki, as well as figures like Jean Cocteau, Ernest Hemingway, and many more. Mendjisky's interactions within this circle, facilitated by his relationship with Kiki, would have provided constant artistic stimulation and exchange. It's noted that Kiki's own art was influenced by Mendjisky, suggesting a reciprocal artistic dialogue between them.

This period was characterized by a spirit of freedom, experimentation, and often, hardship. Artists lived and worked in close proximity, sharing ideas, studios, and models. Mendjisky's presence in this environment was crucial to his development, exposing him to a constant stream of new ideas and artistic approaches.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Maurice Mendjisky passed away in 1951, leaving behind a rich body of work that reflects the artistic dynamism of his time. His legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, he is remembered as a skilled painter who successfully navigated and synthesized various modernist currents – from Cézanne's structuralism to the color innovations of Fauvism and Divisionism, and the expressive freedom of Soutine – all while maintaining a personal touch characterized by sensitivity and warmth.

His contribution to the École de Paris is significant. As one of the many talented émigré artists who made Paris their home, he enriched the city's cultural landscape and participated in the dialogues that shaped modern art. His works are preserved in private collections and, importantly, are championed by institutions like the Musée Mendjisky, ensuring that future generations can engage with his art.

The artistic lineage continued through his son, Serge Mendjisky (1929-2017), who also became a respected artist. Serge studied at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and was influenced by Impressionism and Pointillism, particularly the works of Claude Monet and Georges Seurat. This continuation of artistic pursuit within the family underscores a deep-seated creative tradition.

Maurice Mendjisky's exploration of themes ranging from the sunlit landscapes of Provence to the poignant depictions of children and the historically resonant plans for the Warsaw Ghetto demonstrates the breadth of his artistic vision. His pursuit of "authenticity and harmony," coupled with his technical skill and emotional depth, ensures his place as a noteworthy artist of the 20th century. His life and work offer valuable insights into the cultural ferment of Paris in its artistic heyday and the enduring power of individual expression within a collective movement.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Voice in a Chorus of Modernity

Maurice Mendjisky was more than just a painter of his time; he was an artist who absorbed the revolutionary spirit of early 20th-century Paris and translated it into a distinctive visual language. Born in Poland, he embraced the French capital as his artistic home, becoming a notable member of the École de Paris. His engagement with the legacy of Cézanne, the vibrancy of Fauvism, the structural explorations of Cubism, and the luminous techniques of Divisionism, all filtered through his own sensitive temperament, resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling.

From his evocative landscapes of the French countryside and Mediterranean coast to his insightful portraits, particularly of Kiki de Montparnasse, and his unique project documenting the Warsaw Ghetto, Mendjisky demonstrated a versatile talent and a profound humanism. His relationship with Kiki placed him at the epicenter of Montparnasse's bohemian world, connecting him with a constellation of artists who were collectively redefining art.

Though perhaps not as universally recognized as some of his contemporaries like Picasso, Matisse, or Modigliani, Maurice Mendjisky's contributions are undeniable. His art, characterized by its nuanced color, thoughtful composition, and emotional resonance, continues to speak to audiences today. Through dedicated exhibitions and the efforts of institutions like the Musée Mendjisky, his legacy is preserved, offering a richer, more complete understanding of the diverse talents that constituted the remarkable phenomenon of the School of Paris. He remains a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the spirit of an age and the depths of human experience.