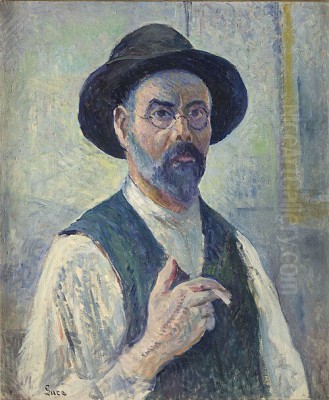

Maximilien Luce stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1858 and living until 1941, Luce was a prolific painter, printmaker, and illustrator whose career spanned the transition from Impressionism through the scientific rigor of Neo-Impressionism, eventually returning to a more personal, albeit still vibrant, style. A man of strong convictions, his working-class origins and anarchist beliefs deeply informed his subject matter, setting him apart from some of his contemporaries. He captured not only the luminous landscapes and bustling cityscapes favoured by the Impressionists but also the gritty reality of industrial labour and the lives of ordinary people, leaving behind a body of work that is both aesthetically compelling and socially resonant.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Maximilien Luce's journey began in the heart of Paris, in the Montparnasse district, a neighbourhood already buzzing with artistic energy. Born into a modest working-class family, his father a railway clerk, Luce's early experiences undoubtedly shaped his lifelong empathy for the labouring classes. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him away from a conventional path and towards the craft of wood engraving.

His formal training commenced with an apprenticeship under the wood engraver Henri-Théodore Hildebrand starting around 1872. Alongside this practical training, Luce pursued evening classes in drawing, honing his foundational skills. He further developed his craft in the workshop of Eugène Froment, where, from 1876, he contributed to various publications, including L'Illustration Nouvelle and Paris Illustré. This period immersed him in the world of graphic arts and illustration, skills that would remain relevant throughout his career.

Seeking broader artistic education, Luce attended the Académie Suisse, a less formal art school known for attracting independent artists, and also studied briefly with the renowned portraitist Carolus-Duran. These experiences exposed him to different artistic approaches and likely fueled his desire to move beyond engraving towards painting, a transition he began making more decisively in the early 1880s. His military service, served between 1879 and potentially extending into the early 1880s, interrupted but did not halt his artistic development.

Embracing Neo-Impressionism

The mid-1880s marked a pivotal moment in Luce's artistic trajectory. He encountered the revolutionary ideas and techniques of Georges Seurat, the pioneer of Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism or Divisionism. Seurat's methodical application of colour theory, using small dots or "points" of pure colour intended to blend in the viewer's eye, offered a new way to capture light and atmosphere with scientific precision.

Luce was captivated by this approach and quickly became one of its most devoted and talented practitioners. He formed close bonds with the leading figures of the movement, including Seurat himself before his untimely death in 1891, and particularly Paul Signac, who became a lifelong friend and fellow advocate for Neo-Impressionist principles. He also associated closely with the elder statesman Camille Pissarro, who briefly adopted the Pointillist technique, and his son Lucien Pissarro.

Luce began exhibiting with the Société des Artistes Indépendants (Society of Independent Artists) in 1887, a crucial venue for avant-garde artists excluded from the official Salon. His work quickly garnered attention. The influential art critic Félix Fénéon, a key champion of Neo-Impressionism, recognized Luce's talent and praised his contributions. Luce, alongside Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Charles Angrand, and Albert Dubois-Pillet, formed the core of the Neo-Impressionist group after Seurat's death, continuing to explore and promote the style.

The Pointillist Technique and Themes

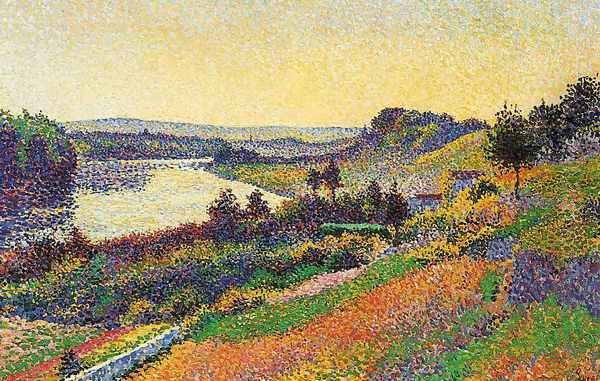

Luce fully embraced the Divisionist technique, meticulously applying small dots and dashes of complementary colours side-by-side. He understood that this method could create effects of extraordinary luminosity and vibrancy, capturing the fleeting effects of light in a manner distinct from the more intuitive brushwork of the Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir. His mastery of colour allowed him to render the shimmer of sunlight on water, the glow of gaslight on city streets, or the intense heat emanating from a factory furnace.

His subject matter was diverse, reflecting both his artistic interests and his social conscience. Like many Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists, he painted landscapes, capturing the tranquil beauty of the Seine riverbanks, the countryside around Lagny, and coastal scenes in Normandy and Brittany. Works like The Seine at Herblay exemplify his ability to render serene natural settings with the characteristic shimmer of Pointillism.

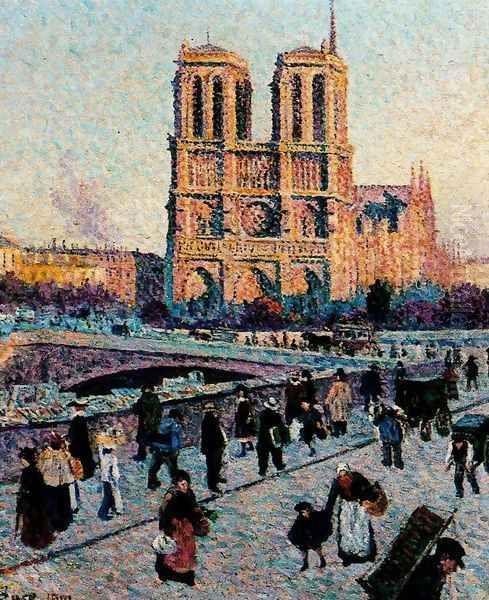

However, Luce distinguished himself through his persistent focus on urban and industrial themes, often infused with his empathy for the working class. He painted numerous views of Paris, not just its famous monuments like Notre Dame, but also its bustling streets, quays, and construction sites. A Street in Paris (often identified as Rue Mouffetard) showcases his ability to capture the energy and structure of the modern city using the Neo-Impressionist technique. He was particularly drawn to industrial landscapes, travelling to the Belgian coal-mining region around Charleroi (the Pays Noir) multiple times. Paintings like The Steelworks (Les Aciéries) or depictions of factories and foundries are powerful testaments to the industrial age, rendered without romanticism but with a profound sense of observation and often highlighting the arduous nature of the labour involved.

Anarchism and Social Conscience

Maximilien Luce was not merely an observer of the working class; he was a committed anarchist and an active participant in the social and political currents of his time. His political beliefs were deeply intertwined with his art and life. He contributed illustrations to numerous anarchist and socialist publications, including Jean Grave's influential journal Les Temps Nouveaux (New Times) and the satirical Père Peinard. His graphic work often directly addressed themes of social injustice, poverty, and the struggles of labourers.

His political affiliations brought him under suspicion from the authorities, particularly during periods of heightened social tension and government crackdowns on anarchist activities. In 1894, following the assassination of French President Sadi Carnot by an Italian anarchist, Sante Geronimo Caserio, Luce was arrested along with many other writers and artists associated with the anarchist movement. He was implicated in the infamous "Trial of the Thirty" (Procès des trente), accused of conspiring to promote anarchist propaganda.

Luce spent several weeks imprisoned in Mazas Prison. While incarcerated, he documented his experience and that of his fellow inmates through sketches and drawings, later compiled into an album titled Mazas. Though eventually acquitted and released, the experience solidified his commitment to his ideals. His art continued to reflect his social conscience, depicting strikes, the hardships faced by workers' families, and the stark contrasts between wealth and poverty in modern society, always portraying his subjects with dignity.

Friendships and Artistic Circles

Throughout his career, Luce maintained important relationships within the Parisian avant-garde. His connection with Paul Signac was particularly enduring; they shared artistic principles, political sympathies, and travelled together, mutually influencing each other's work. The early guidance and camaraderie of Camille Pissarro were also significant, providing a link to the older generation of Impressionists.

Beyond the core Neo-Impressionist group (Seurat, Signac, Cross, Angrand, Dubois-Pillet), Luce interacted with a wider circle. He knew Théo van Rysselberghe, a key figure in Belgian Neo-Impressionism. While direct connections are less documented, his work was certainly known to artists like Vincent van Gogh, who was deeply interested in Pointillism during his time in Paris. Luce remained a steadfast member of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, serving as its vice-president and later president, demonstrating his commitment to providing a platform for independent artistic expression outside the established academic system. His studio and the exhibitions he participated in were meeting points for artists and intellectuals who shared his progressive views.

Evolution and Later Career

While Luce remained associated with Neo-Impressionism for a significant part of his career, his style was not static. Around the turn of the 20th century, and particularly after 1900, his application of the Pointillist technique began to loosen. While still employing divided brushstrokes and a vibrant palette, the strict, methodical dot gave way to broader, more expressive dashes and patches of colour. His work moved towards a style that synthesized the luminosity of Neo-Impressionism with the more fluid handling and subjective response characteristic of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

He continued to paint prolifically, focusing increasingly on landscapes and cityscapes. He produced numerous views of the Seine, explored the landscapes around Rolleboise where he often stayed, and revisited Paris as a subject, capturing its bridges, streets, and monuments with renewed vigour. His series depicting Notre Dame Cathedral from various viewpoints and under different light conditions, created in the early 1900s, are among his most celebrated later works.

Luce travelled, painting scenes in London (like his evocative The Thames in London, Vauxhall Bridge from 1893), the Netherlands, and various regions of France. Throughout the First World War, his work took on a more somber tone, depicting scenes of war-torn landscapes and the suffering it caused, reflecting his pacifist and humanitarian concerns. In his later decades, while perhaps less radically innovative, his painting retained its characteristic energy, strong composition, and sensitivity to light and colour. He continued working until shortly before his death in Paris in 1941, during the German occupation.

Representative Works in Focus

Several key works encapsulate the essence of Maximilien Luce's artistic journey and concerns:

A Street in Paris (Rue Mouffetard) (c. 1889-1890): This painting exemplifies Luce's application of Pointillism to an urban scene. The bustling market street is rendered with vibrant dots of colour that capture the bright sunlight and deep shadows, the movement of the crowd, and the architectural structure of the buildings. It demonstrates his ability to organize a complex scene using the Neo-Impressionist technique while conveying the lively atmosphere of everyday Parisian life.

The Steelworks (Les Aciéries) (c. 1895): Representing his engagement with industrial themes, this work, often depicting the factories of Charleroi, uses the Pointillist style to convey the intense heat, smoke, and activity of a modern steel mill. The glowing reds and oranges contrast with the darker tones of the industrial structures and the night sky, creating a powerful image of human labour within the imposing environment of heavy industry. It reflects his social awareness and his unique contribution to Neo-Impressionist subject matter.

Quai Saint-Michel and Notre-Dame (c. 1901): Part of his series focusing on the iconic cathedral, this painting showcases his later, slightly looser Neo-Impressionist style. The dots and dashes are more visible, the colour harmonies rich and nuanced. Luce captures the grandeur of the cathedral and the bustling activity along the Seine embankment, balancing architectural solidity with the shimmering effects of light on the water and the movement of figures and boats. It highlights his enduring fascination with Paris and his mastery of light effects.

Morning, Interior (Le Matin, Intérieur) (1890): This intimate scene depicts Luce's partner Ambroisine and perhaps their son. It demonstrates his ability to apply the rigorous Pointillist technique to a domestic interior, capturing the subtle play of morning light filtering into the room. The careful division of colour creates a tranquil yet vibrant atmosphere, showcasing a more personal side of his oeuvre while adhering to Neo-Impressionist principles.

The Seine at Herblay (La Seine à Herblay) (1890): A fine example of his landscape painting during his peak Pointillist period. The calm waters of the Seine reflect the sky and trees, rendered in a mosaic of carefully placed colour dots. The painting exudes tranquility and demonstrates Luce's sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere in a natural setting, placing him firmly within the landscape tradition explored by Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists alike.

The Thames in London, Vauxhall Bridge (1893): Resulting from one of his trips to London, this painting captures the hazy atmosphere and industrial character of the Thames. Luce uses Pointillism to render the fog, the reflections on the water, and the silhouettes of bridges and boats, creating an evocative image of the British capital that contrasts with his brighter Parisian scenes. It shows his ability to adapt his technique to different environments and atmospheric conditions.

Legacy and Recognition

Maximilien Luce left behind a substantial and significant body of work. He is recognized as one of the foremost French Neo-Impressionist painters, admired for his technical skill, his vibrant use of colour, and his unique focus on themes of labour and modern urban life. While perhaps not as universally famous as Seurat or Signac, his contributions were crucial to the development and dissemination of the Pointillist style.

His commitment to social justice and his anarchist beliefs add another layer to his significance, positioning him as an artist deeply engaged with the issues of his time. His depictions of the working class are considered among the most powerful and empathetic artistic representations of labour from that era.

Today, Luce's paintings, drawings, and prints are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. His work continues to be appreciated by collectors; in 2011, a version of his Notre-Dame de Paris achieved a record price at auction, signalling sustained interest in his art.

His influence extended beyond his immediate circle. The bold colour experiments of the Neo-Impressionists, including Luce, paved the way for later movements like Fauvism, influencing artists such as Henri Matisse and André Derain. Luce remains an important figure for understanding the evolution of modern art in France, representing a unique confluence of artistic innovation and social conscience. His contemporary, Paul Cézanne, pursued a different path towards modernism, but Luce's dedication to structure and light within the Neo-Impressionist framework offers a fascinating parallel exploration of form and perception at the turn of the century.

Conclusion

Maximilien Luce's life and art offer a compelling narrative of dedication – dedication to his craft, to the principles of Neo-Impressionism, and to his deeply held social and political beliefs. From his beginnings as a wood engraver to his status as a leading Pointillist painter, he consistently sought to capture the essence of modern life in all its facets, from the luminous beauty of the French landscape to the harsh realities of the industrial age and the dignity of human labour. His vibrant canvases, marked by their scientific precision and profound empathy, secure his place as a significant master of French Post-Impressionism and a chronicler of his turbulent times. His legacy endures not only in the visual power of his art but also in the example of an artist who dared to integrate his aesthetic vision with a passionate engagement with the world around him.