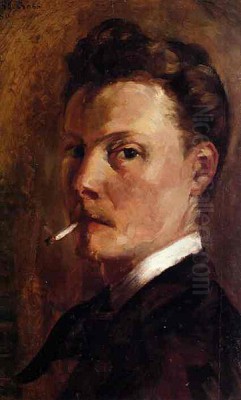

Henri-Edmond Cross stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born Henri-Joseph Delacroix, he navigated the evolving artistic landscape, transitioning from early realism to become a master of Neo-Impressionism and a significant influence on subsequent movements. His dedication to the scientific principles of color and light, combined with a profound love for the Mediterranean landscape, resulted in a body of work celebrated for its harmony, luminosity, and innovative technique.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Henri-Joseph Delacroix was born on May 20, 1856, in Douai, located in the Nord department of France. His heritage was a blend of French and British, with a French father who worked as a blacksmith and a British mother. This background provided a foundation far removed from the established art world, yet artistic talent surfaced early in the young Henri.

Recognizing his nephew's potential, his cousin Dr. Auguste Soins, himself an art enthusiast, provided crucial early encouragement and guidance. Under Soins's tutelage, Henri began his first drawing lessons around the age of ten. This initial spark ignited a passion that would define his life, setting him on a path towards artistic exploration.

Formal training followed. In 1876, while pursuing legal studies in the nearby city of Lille, Cross simultaneously enrolled at the Écoles Académiques de Dessin et d'Architecture, later known as the École des Beaux-Arts of Lille. Here, he honed his foundational skills, immersing himself in the academic traditions while likely absorbing the burgeoning artistic ideas circulating at the time.

Parisian Studies and a Change of Name

The lure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world, proved irresistible. In 1878, Cross relocated to the capital to further his artistic education. He joined the studio of Émile Auguste Carles, a respected painter known for his portraiture and genre scenes. Studying under Carles provided Cross with valuable experience and exposure to the Parisian art scene.

His early works from this period reflected the prevailing tastes, often characterized by a darker, more realistic palette. Influences from established masters like Gustave Courbet can be discerned in these initial efforts, showcasing a solid grounding in traditional representation before his stylistic evolution began.

A significant step in establishing his individual artistic identity occurred in 1881. When he first exhibited his work at the Salon, he chose to sign his paintings as "Henri Cross." This decision was a practical one, made consciously to distinguish himself from the immensely famous Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. This simple change marked the beginning of his public artistic persona.

Encountering Impressionism and Embracing Light

The early 1880s were a period of profound transformation for Cross. Encounters with leading figures of Impressionism drastically altered his artistic direction. Meeting Claude Monet, a master of capturing fleeting light and atmospheric effects, was particularly impactful. He also became acquainted with the work of Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to composition and color would leave a lasting impression.

Inspired by these encounters and the broader Impressionist movement, Cross began to abandon the somber tones of his earlier Realist phase. His palette brightened considerably, embracing the vibrant hues and broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism. He started exploring the effects of natural light, particularly in outdoor settings, aligning himself with the Impressionists' focus on capturing the ephemeral qualities of nature. Camille Pissarro was another Impressionist whose work likely informed Cross's evolving style during this period.

This shift towards a lighter, more luminous approach laid the groundwork for his next major artistic leap. The Impressionist emphasis on color and light resonated deeply with Cross, paving the way for his engagement with the more systematic color theories of Neo-Impressionism.

The Birth of Neo-Impressionism and the Société des Artistes Indépendants

The mid-1880s marked Cross's full immersion into the avant-garde. He became closely associated with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, the leading proponents of a new artistic theory known as Neo-Impressionism, or Pointillism (also referred to as Divisionism). This technique involved applying small, distinct dots or points of pure color to the canvas, relying on the viewer's eye to optically blend them, creating a more vibrant and luminous effect than traditional color mixing.

In 1884, Cross played a crucial role, alongside Seurat, Signac, Charles Angrand, and Albert Dubois-Pillet, in founding the Société des Artistes Indépendants. This organization was established as a radical alternative to the official Salon, which often rejected experimental or unconventional art. The Indépendants operated under the principle of "no jury, no awards," providing a vital platform for avant-garde artists to exhibit their work freely. Cross's involvement underscored his commitment to artistic innovation and independence.

Further solidifying his identity within this new movement, he formally adopted the name "Henri-Edmond Cross" in 1886. This final name change coincided with his deepening commitment to the principles and techniques of Neo-Impressionism, marking his definitive arrival as a key figure in the movement.

Mastering Pointillism and the Mediterranean Influence

Cross quickly mastered the demanding technique of Pointillism. His application of color theory, likely influenced by the scientific writings of Charles Blanc and Ogden Rood that also informed Seurat, was both rigorous and intuitive. He juxtaposed complementary colors in small dots, creating shimmering surfaces that captured the intensity of light with remarkable vibrancy.

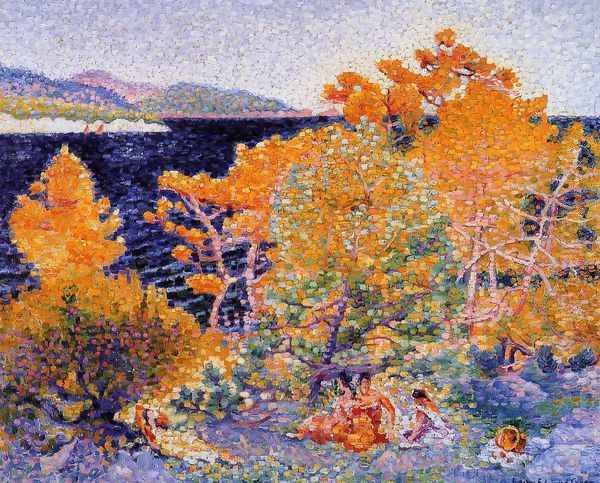

Unlike Seurat's often monumental and somewhat rigid compositions, Cross's Pointillism frequently possessed a more lyrical and decorative quality. His dots could vary in size and shape, contributing to the texture and rhythm of the painting. This approach allowed for a harmonious balance between the scientific application of color and a deeply personal, expressive response to the subject matter.

A significant factor shaping his mature style was his move to the south of France in 1891. Seeking relief from chronic rheumatism, which plagued him throughout his life, he settled first in Cabasson and later permanently in Saint-Clair, near Le Lavandou. The brilliant light and stunning landscapes of the French Riviera became his primary inspiration. The Mediterranean coast, with its azure waters, vibrant flora, and sun-drenched vistas, provided the perfect subject matter for his luminous, color-saturated canvases.

Signature Themes and Representative Works

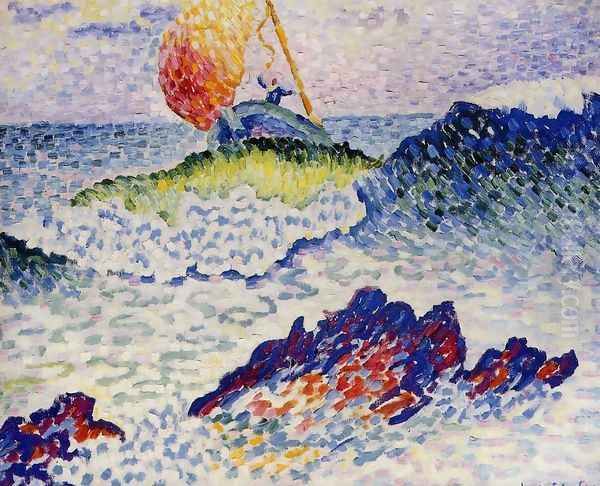

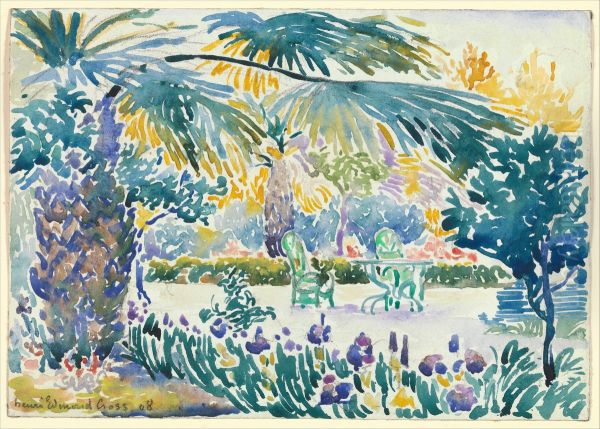

Cross's oeuvre is dominated by landscapes, seascapes, and garden scenes, often populated by idyllic figures. His deep connection to the natural world, particularly the Mediterranean environment, is evident in the majority of his paintings and watercolors.

Among his most celebrated works are those capturing the essence of the southern French coast. The Evening Air (also known as L'Air du Soir, c. 1893-1894), often cited alongside studies like Evening Breeze (Study for Pine Forest) and Seaside with Sailboats in the Distance (Study for Evening Breeze), exemplifies his ability to translate the tranquility and specific light of dusk into harmonious patterns of color dots. The painting radiates a serene, almost dreamlike atmosphere.

His depictions of Venice, such as The Basin of Saint-Marc, Venice and Landscape of the Saint-Marc Basin, showcase his skill in rendering architectural forms and water reflections using the Pointillist technique, capturing the unique luminosity of the city. Works like Beach at Cabasson (or Cap Nègre) and Beach at Monte Carlo further demonstrate his fascination with the coastline, translating the intense sunlight and vibrant colors of the Riviera onto canvas.

Cross also explored figurative subjects within these landscapes. The Fisherman (1895), housed in the Kröller-Müller Museum, integrates the human form seamlessly into the shimmering, pointillist environment. Swimmers (Study) suggests his interest in depicting figures in motion within natural settings. Even his still lifes, like Rose Buds, demonstrate his meticulous attention to color harmony and light.

His work as a printmaker is also noteworthy. The Wanderer (1896), a lithograph, reflects perhaps his anarchist sympathies and interest in social themes, depicting a solitary figure journeying through a stylized landscape. Prints like Cap Nègre Puzzle and the image known as The Flowered Terrace, 1905 Metal Print show his continued exploration of Neo-Impressionist principles in different media. Other works mentioned, such as Oasis in the Sunshine, Water Lilies in the Garden, Woman Tying Sticks, Peasant Woman Carrying a Basket, and The Amaryllis Boat (or The Barge, 1905-1908), further illustrate the breadth of his subject matter within his signature style.

Later Style and the Bridge to Fauvism

In the later stages of his career, particularly after the turn of the century, Cross's style continued to evolve. While remaining rooted in the principles of Divisionism, his brushwork often became broader and more expressive. The small, precise dots sometimes gave way to larger, more rectangular strokes, resembling mosaic tesserae.

This later phase saw an even greater emphasis on pure, intense color. He sometimes left areas of white canvas or paper exposed between the strokes, further enhancing the brilliance and vibration of the hues. This technique, pushing the boundaries of Neo-Impressionism, is widely seen as a crucial bridge towards Fauvism.

Indeed, younger artists like Henri Matisse were profoundly influenced by Cross's work during this period. Matisse visited Cross in Saint-Clair in 1904, and the experience is considered a catalyst for Matisse's own experiments with bold color and expressive form, famously demonstrated in his painting Luxe, Calme et Volupté, painted shortly after his stay near Saint-Tropez where Signac also resided. Cross's late works, with their heightened color and increasingly abstract quality, clearly prefigure the Fauvist explosion of color that would erupt in 1905.

Personal Beliefs and Health Challenges

Beyond his artistic contributions, Cross held strong personal convictions. He was known to sympathize with anarchist ideals, sharing this inclination with his close friend and fellow Neo-Impressionist Paul Signac. While his art rarely carried overt political messages, themes of harmony with nature and idyllic, utopian landscapes can perhaps be interpreted through this lens, suggesting a yearning for a simpler, more egalitarian existence. The aforementioned print, The Wanderer, might also hint at these individualistic or anti-establishment sentiments.

His life was significantly impacted by persistent health problems. Chronic rheumatism and arthritis caused him considerable pain and affected his mobility, necessitating his move to the warmer climate of the South. Despite these physical challenges, he maintained remarkable productivity throughout his career.

In his final years, his health deteriorated further. He battled cancer, undergoing treatment in 1909. Even during this difficult time, his dedication to his art remained unwavering. A controversy sometimes mentioned involves his later work, The Shipwreck (1906-1907), where the juxtaposition of bright, almost cheerful colors with the depiction of human figures facing disaster was seen by some as unsettling or emotionally detached, highlighting a tension between decorative beauty and tragic subject matter.

Legacy and Recognition

Henri-Edmond Cross passed away from cancer on May 16, 1910, in Saint-Clair, the Mediterranean haven that had inspired so much of his greatest work. He was just shy of his 54th birthday. His death was a significant loss to the art world, particularly to the Neo-Impressionist circle and the younger artists he had inspired.

Today, Cross is recognized as one of the most important figures of Neo-Impressionism, alongside Seurat and Signac. While perhaps less famous than Seurat, his unique contribution lies in his lyrical interpretation of the Pointillist technique and his masterful evocation of the Mediterranean light and landscape. His influence extended beyond his immediate circle, significantly impacting the development of Fauvism and subsequent color-based movements in modern art.

His works are held in major museum collections around the world, attesting to his enduring importance. Prestigious institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands, proudly display his luminous paintings and watercolors.

Conclusion

Henri-Edmond Cross carved a unique path through the dynamic art world of fin-de-siècle France. From his early academic training and Realist beginnings, he embraced the light of Impressionism before becoming a leading practitioner and innovator of Neo-Impressionism. His meticulous yet expressive Pointillist technique, combined with his profound sensitivity to the colors and atmosphere of the Mediterranean, resulted in works of exceptional harmony and radiance. Battling physical ailments while holding firm to his artistic and personal convictions, Cross not only created a significant body of beautiful work but also played a crucial role in bridging the gap between Neo-Impressionism and the bold color experiments of Fauvism, securing his legacy as a vital figure in the history of modern art.