Menachem Shemi, born Menachem Schmidt in 1897 in the Russian Empire and passing away in Israel in 1951, stands as a significant, albeit sometimes under-sung, figure in the nascent narrative of Israeli modern art. His journey from the art academies of Eastern Europe to the sun-drenched landscapes of Palestine, and his subsequent evolution as an artist, mirrors the complex cultural and national aspirations of the Jewish Yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine). Shemi's work is characterized by a distinctive lyrical quality, a deep connection to the land, and an evolving palette that captured both the physical and spiritual essence of his adopted homeland.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born into a Jewish family in Bobruisk, Russian Empire (present-day Belarus), Menachem Schmidt's early artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training. He initially studied at the Odessa Art Academy, a notable institution that nurtured several artists who would later contribute to Jewish and Israeli art. The environment in Odessa, a cosmopolitan port city with a vibrant Jewish cultural life, likely exposed him to diverse artistic currents. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation seeking new horizons and a more direct engagement with modernism, Schmidt felt the pull of change.

In 1913, at the young age of sixteen, he made the pivotal decision to immigrate to Palestine, then under Ottoman rule. This move was part of the Second Aliyah, a wave of Jewish immigration driven by a mix of Zionist ideals and the desire to escape persecution in Eastern Europe. Upon arrival, he enrolled in the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem. Founded by Boris Schatz in 1906, Bezalel was the cornerstone of early artistic endeavors in the Yishuv, aiming to create a new "Hebrew" art that blended European techniques with biblical themes and Oriental motifs.

Shemi's time at Bezalel, however, was marked by a burgeoning artistic independence. He, along with other students, reportedly found the institution's traditional, somewhat academic, and crafts-oriented approach restrictive. This tension between the established vision of Bezalel and the younger generation's yearning for more contemporary European styles was a recurring theme in the school's early history. Shemi eventually left Bezalel, driven by a desire to forge his own artistic path, one that would authentically reflect his personal vision and the unique character of the land he now called home. He sought to define what it meant to be a Jewish-Israeli artist, moving beyond established European norms while still engaging with them.

The Evolution of a Distinctive Style: From Somber Tones to Luminous Landscapes

The 1920s marked the true beginning of Shemi's independent artistic career and are considered part of the foundational period of modern Israeli art. His early works, influenced perhaps by his Russian training or the initial struggles of an immigrant artist, were often characterized by more somber, earthy tones. However, as he immersed himself in the landscapes and life of Palestine, his palette began to transform.

A defining characteristic of Shemi's mature style became his use of vivid, yet nuanced, colors. He developed a particular affinity for what has been described as an "Arab blue-green," a distinctive hue that captured the unique interplay of light, sky, and vegetation in the region. His paintings increasingly took on a bright, almost dreamlike quality, imbued with a sense of lyricism and sometimes a mystical atmosphere. This was particularly evident in his depictions of Safed (Tzfat), the ancient Galilean city renowned for its spiritual heritage and Kabbalistic traditions.

Shemi was deeply connected to Safed and became one of the founders of its artists' colony, a vibrant community that attracted many painters and sculptors drawn to the city's picturesque alleys, ancient synagogues, and ethereal light. His Safed landscapes are not mere topographical representations; they are imbued with an emotional resonance, capturing the city's unique spiritual aura. He often employed simplified forms, sometimes with a degree of expressive distortion, to convey the essence rather than a literal depiction of his subjects. Dome-like structures, characteristic of the local architecture, frequently appear in his compositions, further rooting his work in the Oriental milieu.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Menachem Shemi's oeuvre primarily focused on landscapes, cityscapes, and scenes of local life. He painted the rolling hills of the Galilee, the bustling streets of coastal cities like Haifa and Acre (Akko), and the intimate courtyards and interiors that defined the everyday existence of the Yishuv.

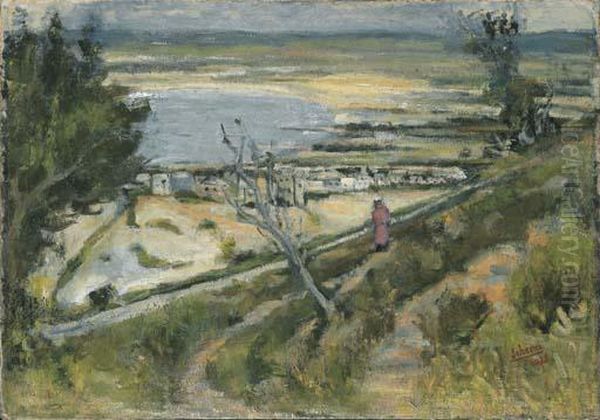

Among his notable works, "Haifa Bay" (1938) exemplifies his ability to capture the expansive beauty of the Israeli coastline. The painting likely showcases his characteristic color palette and his skill in rendering the atmospheric effects of light on water and land. Haifa, a rapidly developing port city during this period, was a common subject for artists, symbolizing the dynamism and growth of the Yishuv.

"The Café" (1936) offers a glimpse into the social fabric of the time. Cafés were important meeting places for artists, intellectuals, and the general public in cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa. Shemi's depiction would have captured the ambiance of these establishments, perhaps with an emphasis on the figures and their interactions, rendered in his increasingly expressive style.

His depictions of Safed are particularly significant. Works like "Interior of a Synagogue in Safed" (1941) and "Courtyard in Safed" (1947) highlight his deep engagement with the city. The synagogue interior would have allowed him to explore themes of spirituality, tradition, and the play of light in enclosed, sacred spaces. The courtyard scene would reflect the intimate, communal life of the ancient city, rendered with his characteristic sensitivity to color and form.

Other important works include "Street in Acre" (1936), which would have captured the historic character of the ancient port city, likely emphasizing its stone architecture and narrow, winding lanes. These paintings, now held in various Israeli museums and private collections, including the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Haifa Museum of Art, serve as testaments to his artistic vision.

Shemi in the Context of Early Israeli Art and Contemporaries

Menachem Shemi was an active participant in the burgeoning art scene of Palestine. He was part of a generation of artists grappling with the challenge of creating a new, local art form. This "Eretz Israel style" (Land of Israel style) sought to move away from the diasporic themes and European academicism of the past, focusing instead on the immediate reality of the land, its light, its people, and the pioneering spirit of the Yishuv.

Shemi's work can be seen in dialogue with that of his contemporaries. Artists like Reuven Rubin, perhaps the most internationally recognized Israeli artist of that era, also focused on the landscapes and people of Palestine, often with a naive, idyllic quality. Nahum Gutman, another prominent figure, was known for his vibrant depictions of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, as well as biblical scenes re-imagined in the local landscape. Israel Paldi developed a more primitivist style, while Zionah Tagger brought a distinctly modern, often French-influenced sensibility to her paintings of local scenes.

The influence of French art, particularly Post-Impressionism and the School of Paris, was significant for many artists in Palestine. Shemi himself was aware of these trends. In a notable contribution to the local art scene, he organized an exhibition in Tel Aviv in 1936 that featured works by prominent Jewish artists of the School of Paris, including Chaïm Soutine, Moïse Kisling, and Marc Chagall. This exhibition was a landmark event, exposing local artists and the public to contemporary European art and stimulating further artistic exploration.

Shemi's style, while sharing the Eretz Israel artists' focus on local subject matter and bright palettes, often possessed a more introspective and lyrical quality. He was associated with a group of artists sometimes referred to as the "Safed mystics," who, like Mordecai Levanon or later Moshe Castel (in his earlier phases), were drawn to the spiritual and historical resonance of places like Safed and Jerusalem. While not as overtly symbolic as an artist like Mordecai Ardon, who also had strong Bezalel connections and a deep interest in Jewish mysticism, Shemi's work conveyed a profound sense of place that transcended mere representation.

He also shared common ground with artists like Arie Aroch and Chaim Atar (Litwak) in their search for an authentic local expression that could synthesize Eastern and Western influences. Aroch, in particular, would later become a pivotal figure in Israeli art, moving towards abstraction but always retaining a connection to personal memory and local motifs. Shemi's generation laid the groundwork for later movements like the "New Horizons" (Ofakim Hadashim) group, led by artists such as Yosef Zaritsky, Yehezkel Streichman, and Avigdor Stematsky, who pushed Israeli art further towards lyrical abstraction, though often still rooted in the Israeli landscape. Even earlier figures like Yitzhak Frenkel (Frenel), who brought direct experience of Parisian modernism to Palestine in the 1920s, helped shape the environment in which Shemi developed.

Personal Tragedy and Later Life

Menachem Shemi's life was marked by a profound personal tragedy that deeply impacted his later years. His son, Aharon "Jimmy" Shemi, was a soldier in the Palmach, the elite fighting force of the Haganah (the Yishuv's underground army). Jimmy was killed in action during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (Israel's War of Independence), a devastating loss for the artist.

In response to this tragedy and at the request of his son's comrades, Menachem Shemi designed a poignant and powerful memorial monument for the fallen soldiers of the Harel Brigade, located at the Kiryat Anavim military cemetery in the Judean Hills, where his son was buried. This abstract stone sculpture, known as the "Palmach Memorial," is a departure from his painting practice but stands as a significant work of commemorative art. It expresses the raw grief and solemn remembrance of a generation that paid a heavy price for statehood. The monument's stark, modernist forms convey a sense of enduring strength and sacrifice.

This personal loss undoubtedly cast a shadow over Shemi's final years. He passed away in 1951, only three years after the death of his son and the establishment of the State of Israel, for which Jimmy had fought. Menachem Shemi himself was buried in the Kiryat Anavim cemetery, near his son and the memorial he designed.

Signature and Artistic Identity

An interesting aspect of Shemi's artistic practice was the variation in his signature. He used different spellings and forms, including "Schmidt," "Shemi," "Shmidt," and sometimes signed in Hebrew. This fluidity might reflect his transition from a European émigré to an Israeli artist, his engagement with multiple linguistic and cultural contexts, or simply personal preference at different stages of his career. The adoption of the Hebraized surname "Shemi" (meaning "my name" or related to "sky/heaven") was a common practice among immigrants seeking to forge a new identity in their homeland.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Menachem Shemi's contribution to Israeli art lies in his sensitive and lyrical interpretations of the Land of Israel, his distinctive use of color, and his role as a pioneer in shaping a local artistic vernacular. He was part of a crucial generation that bridged European artistic traditions with the unique environment and aspirations of the Yishuv. His works capture a specific moment in Israeli history, reflecting the optimism, the challenges, and the deep spiritual connection to the land that characterized the pre-state era and the early years of Israeli independence.

While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his contemporaries like Rubin or Gutman, Shemi's paintings are treasured in Israel and are considered important examples of the "Eretz Israel style." His depictions of Safed, in particular, remain iconic, capturing the city's mystical allure. His work is regularly featured in exhibitions on early Israeli art, and his legacy is preserved in the collections of Israel's major museums.

He is remembered as an artist who sought an authentic voice, one that could express the nuances of light, color, and spirit in his adopted homeland. His journey from the academies of Russia to the hills of Galilee, his stylistic evolution, and his poignant personal story all contribute to the rich tapestry of Israeli art history. Menachem Shemi's paintings continue to resonate with viewers for their lyrical beauty and their heartfelt evocation of a land undergoing profound transformation. His art remains a testament to the enduring power of place and the individual artist's quest for meaning and expression.