Otto Freundlich stands as a seminal yet often tragically overlooked figure in the annals of 20th-century art. A German-born Jewish artist, he was a pioneering force in the development of abstract art, a dedicated sculptor, a painter of vibrant, spiritually infused compositions, and a designer of luminous stained glass. His life, deeply enmeshed with the tumultuous artistic and political currents of his time, was cut short by the barbarity of the Nazi regime. This article seeks to illuminate Freundlich's significant contributions to modern art, trace his artistic journey, explore his philosophical underpinnings, and commemorate his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on July 10, 1878, in Stolp, Pomerania, then part of the German Empire (now Słupsk, Poland), Otto Freundlich's early life did not immediately point towards a career in the visual arts. He initially pursued commercial training, a practical path that perhaps belied the artistic ferment brewing within him. He also briefly delved into dentistry and later art history, studying in both Munich and Berlin. These academic explorations, particularly in art history, likely provided him with a foundational understanding of artistic traditions, which he would later both absorb and radically depart from.

The true turning point came in his late twenties. A visit to Florence in 1904-1905 exposed him to the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, an experience that often proves transformative for aspiring artists. However, it was the burgeoning modernist movements that would truly capture his imagination. By 1908, Freundlich made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde art world.

The Parisian Crucible: Cubism and Early Abstractions

Paris in the early 20th century was a melting pot of revolutionary artistic ideas. Freundlich arrived at a time when Cubism, spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, was shattering traditional modes of representation. He quickly immersed himself in this vibrant milieu, establishing a studio in Montmartre at the famed Bateau-Lavoir, a dilapidated complex of artists' studios that also housed Picasso, Juan Gris, and other luminaries.

The influence of Cubism on Freundlich's early work is discernible, particularly in its fragmentation of form and its exploration of multiple perspectives. However, Freundlich was never a mere follower. He absorbed the principles of Cubism but began to steer them towards a more purely abstract and spiritually resonant direction. He shared a studio for a time with the German artist Otto van Wätjen and became acquainted with a wide circle of international artists, including the Dutch painter Kees van Dongen and the sculptor Alexander Archipenko. His friendship with Walter Gropius, the future founder of the Bauhaus, also dates from this period, indicating his early engagement with progressive architectural and design ideas.

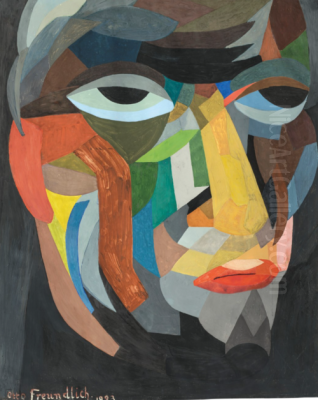

His painting Composition (1911), now in the collection of the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, exemplifies this early phase. While it retains a connection to Cubist structure, its emphasis on dynamic color planes and non-objective forms signals his move towards a unique abstract language. He was less interested in deconstructing objects than in constructing new visual realities built from color and form, imbued with an almost cosmic energy.

Development of a Distinctive Abstract Vision

Freundlich's artistic journey was characterized by a profound belief in the spiritual and social power of art. He saw abstraction not as an escape from reality, but as a means to access a deeper, more universal truth. His paintings evolved into complex tapestries of interlocking, often curvilinear, colored shapes. Unlike the more analytical or austere abstraction of some of his contemporaries, Freundlich's work pulsed with warmth and a sense of organic growth.

Color was paramount in his work. He developed a sophisticated understanding of color relationships, using them to create harmony, tension, and emotional resonance. Titles such as My Sky is Red (1933) suggest a deeply personal and symbolic connection to color, where hues transcend mere description to embody states of being or philosophical concepts. His compositions often feel as though they are expanding beyond the confines of the canvas, suggesting an infinite, interconnected universe.

He was also a dedicated sculptor. His most famous sculptural work, Der Neue Mensch (The New Man), created in 1912, is a powerful, totemic figure. Composed of block-like, abstracted human forms, it embodies his utopian vision of a renewed humanity. This sculpture, with its monumental presence, would later gain tragic notoriety. Another significant sculpture, Der Große Kopf (The Large Head) or Ascension (1928), further explored themes of spiritual ascent and human potential through abstracted forms.

Freundlich's commitment to art extended beyond painting and sculpture. He was deeply interested in applied arts, particularly stained glass and mosaic. These media, often associated with communal and architectural spaces, aligned with his belief in art's social role. He created numerous designs for stained glass windows, where his mastery of color could be translated into light, creating immersive, spiritual environments. These works, unfortunately, are less well-documented, partly due to the destructions of war.

Engagement with Avant-Garde Movements

Throughout his career, Freundlich was an active participant in several key avant-garde movements, though he always maintained a distinct artistic independence. His engagement reflects his commitment to collaborative artistic endeavors and his desire to push the boundaries of modern art.

In Germany, he was associated with the November Group (Novembergruppe), an association of radical artists and architects formed in Berlin in the wake of the German Revolution of 1918-19. The group aimed to bring art and society closer, a goal that resonated deeply with Freundlich's own ideals. He also played a role in the Dada movement, particularly in Cologne, where he collaborated with Max Ernst and Johannes Theodor Baargeld in organizing Dada exhibitions. Dada's anti-bourgeois stance and its questioning of artistic conventions would have appealed to Freundlich's revolutionary spirit.

He was also connected with the Cologne Progressives (Gruppe progressiver Künstler Köln), a group active in the 1920s and early 1930s that included artists like Franz Wilhelm Seiwert and Heinrich Hoerle. This group advocated for a socially committed art, often employing figurative constructivist styles to address political themes, aligning with Freundlich's own leftist leanings.

Back in Paris, Freundlich became a key member of Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square), an international group of abstract artists founded in 1929 by Joaquín Torres-García and Michel Seuphor. This group brought together diverse strands of abstract art, from the geometric abstraction of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg to the more organic abstraction of Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Freundlich exhibited with Cercle et Carré in their landmark 1930 exhibition.

When Cercle et Carré dissolved, many of its members, including Freundlich, joined Abstraction-Création, founded in 1931. This larger and more influential association became a crucial platform for non-figurative art in the 1930s, publishing annual albums and organizing exhibitions. Its membership was a veritable who's who of abstract art, including Wassily Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, Georges Vantongerloo, and Antoine Pevsner. Freundlich's involvement in these groups underscores his central position within the international abstract art scene.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Art, Society, and Utopia

Freundlich's art was inextricably linked to his philosophical and political beliefs. He was a utopian thinker, deeply influenced by socialist and, some argue, communist ideals, though his "cosmic communism" was more a spiritual and artistic vision than a strict political doctrine. He believed in the transformative power of art to foster a more harmonious and equitable society. For Freundlich, art was not a luxury but a fundamental human need, a tool for spiritual enlightenment and social construction.

He envisioned a future where art would be integrated into everyday life, accessible to all, and a catalyst for collective well-being. This is reflected in his interest in mosaics and stained glass, media that lend themselves to public and communal spaces. His abstract forms, with their emphasis on harmony and interconnectedness, can be seen as visual metaphors for an ideal society. He wrote extensively on his theories, articulating a vision of art as a constructive force, capable of shaping human consciousness and building a better world. His writings, though not as widely known as his visual art, provide crucial insights into the intellectual framework of his practice.

This belief in art's social mission put him in direct opposition to the rising tide of fascism in Europe, which sought to control and instrumentalize art for its own propagandistic purposes, while denigrating any art that did not conform to its narrow, reactionary aesthetic.

The Shadow of Nazism: "Degenerate Art"

The rise of the Nazi Party in Germany in 1933 marked a dark turn for modern art and for artists like Freundlich, who were Jewish and proponents of avant-garde styles. The Nazis systematically persecuted modern art, which they branded "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art). This term was used to condemn art that was abstract, expressionist, surrealist, or created by Jewish, communist, or otherwise "undesirable" artists.

Freundlich's work became a prime target. In 1937, the Nazis organized the infamous "Entartete Kunst" exhibition in Munich, designed to ridicule and vilify modern art. Tragically, Otto Freundlich's sculpture Der Neue Mensch (The New Man) was chosen for the cover of the exhibition catalogue. The sculpture was photographed from a low, unflattering angle, its features distorted to make it appear grotesque, and it was juxtaposed with derogatory slogans. This act was a deliberate attempt to defame Freundlich and to symbolize the supposed "degeneracy" of modernism.

Many of Freundlich's works in German public collections were confiscated. Some were sold abroad to raise foreign currency, while others were tragically destroyed. The Nazi campaign against "degenerate art" was not just an aesthetic purge; it was a cultural war aimed at eradicating intellectual freedom and diversity. For Freundlich, who had dedicated his life to art as a force for humanism and progress, this persecution must have been devastating.

Final Years and Tragic End

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Freundlich, who was living in France, was interned by the French authorities as an enemy alien (being German). He was released but, following the German invasion and occupation of France in 1940, his situation became increasingly perilous. As a Jew and a prominent "degenerate" artist, he was in grave danger.

He sought refuge in the Pyrenees in southwestern France, living in hiding with his partner, Jeanne Kosnick-Kloss, also an artist. They endured difficult conditions, constantly under threat. Despite attempts by friends and organizations like Varian Fry's Emergency Rescue Committee to help him escape to the United States, these efforts proved unsuccessful.

The end came in 1943. On February 23, Otto Freundlich was arrested by the Gestapo in Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet. He was deported to the Majdanek concentration and extermination camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. According to historical records, Otto Freundlich was murdered on March 9, 1943, the very day he arrived at Majdanek. He was 64 years old. His death was a profound loss to the art world and a stark reminder of the human cost of Nazi brutality.

Posthumous Recognition and Legacy

For many years after his death, Otto Freundlich's work remained relatively obscure, overshadowed by the tragedy of his life and the dispersal or destruction of many of his pieces. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his art and his contributions to modernism.

Museums and galleries have played a crucial role in this re-evaluation. The Musée Tavet-Delacour in Pontoise, France, holds a significant collection of his works, thanks in part to donations from his estate. His paintings can also be found in major institutions such as the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Staatliche Kunsthalle Mannheim.

Several important retrospective exhibitions have brought his oeuvre to a wider audience. A landmark exhibition titled "Otto Freundlich: Cosmic Communism" was held at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne in 2017, and subsequently traveled to the Kunstmuseum Basel and the Tate Liverpool. This exhibition showcased the breadth of his work, including paintings, sculptures, mosaics, and stained glass designs, and highlighted his utopian artistic vision. In 2020, the Musée de Montmartre in Paris hosted "Otto Freundlich: The Revelation of Abstraction," further cementing his place in the history of art. His works have also been featured in group exhibitions, such as "Reconstruction – German Art Positions" at the Nanjing Art Institute Art Museum in 2019.

Freundlich's legacy is multifaceted. He is recognized as one of the earliest pioneers of purely abstract painting, developing a unique visual language characterized by vibrant color, dynamic forms, and a profound spiritual dimension. His sculptures, particularly Der Neue Mensch, stand as powerful statements of humanist ideals, tragically co-opted and vilified by a destructive regime.

Beyond his artistic innovations, Freundlich's life story serves as a poignant testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring power of art in the face of oppression. He represents the countless artists whose lives and careers were brutally impacted by Nazism. His unwavering commitment to his artistic and social ideals, even in the darkest of times, continues to inspire.

Conclusion

Otto Freundlich was more than just an artist; he was a visionary who believed in the capacity of art to shape a more humane and enlightened world. From his early encounters with Cubism in Paris to his mature abstract compositions and his utopian sculptures, his work was driven by a profound spiritual and social consciousness. He navigated the complex currents of the European avant-garde, contributing significantly to movements like Dada, Cercle et Carré, and Abstraction-Création, while always maintaining his unique artistic voice.

The persecution he endured under the Nazi regime, culminating in his murder at Majdanek, is a tragic chapter in the history of 20th-century art. Yet, despite the efforts to silence him and erase his contributions, Otto Freundlich's art has endured. Through the dedicated efforts of scholars, curators, and institutions, his work is increasingly recognized for its innovation, its beauty, and its profound message of hope and humanism. He remains a vital figure for understanding the trajectory of abstract art and the complex interplay between art, politics, and society in a turbulent era. His sky, though he once painted it red with passion and vision, was ultimately darkened by hatred, but his artistic light continues to shine.