Michel Corneille the Younger, often distinguished by the epithet "des Gobelins" due to his long association with the famous royal manufactory, stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of 17th-century France. Born in Paris in 1642 and passing away in the same city on August 16, 1708, his life and career were deeply intertwined with the flourishing of French classicism under the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. As a painter, etcher, and engraver, Corneille contributed to the rich artistic tapestry of his era, navigating the powerful influences of his father, his esteemed teachers, and the pervasive allure of Italian art.

An Artistic Heritage: Early Life and Influences

Michel Corneille the Younger was born into an artistic dynasty. His father, Michel Corneille the Elder (c. 1601–1664), was a respected painter from Orléans, a founding member of the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1648, and later its rector in 1656. This familial environment undoubtedly provided the young Michel with his earliest exposure to art and artistic practice. Growing up amidst discussions of technique, composition, and the grand traditions of painting, he was naturally predisposed to follow in his father's footsteps.

His formal training extended beyond his father's studio. He had the distinct advantage of studying under two of the most dominant figures in French art of the period: Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) and Pierre Mignard (1612–1695). Le Brun, as First Painter to the King and director of the Gobelins Manufactory and the Académie, was the principal arbiter of artistic taste and the driving force behind the grand decorative schemes at Versailles. Mignard, though often positioned as Le Brun's rival, was also a highly accomplished artist, particularly renowned for his portraiture and his own elegant, Italianate style. Learning from these masters provided Corneille with a solid foundation in the academic principles of drawing, composition, and the hierarchy of genres, which placed history painting at its apex.

The artistic atmosphere of Paris at this time was electric. The Académie Royale, established to elevate the status of artists and to provide a structured system of training, was central to this. Figures like Eustache Le Sueur (1616–1655), though from a slightly earlier generation, had already laid groundwork for a distinctly French classical style, drawing inspiration from Raphael and Poussin. The influence of Simon Vouet (1590–1649), who had brought the Italian Baroque style to France and was a teacher to Michel Corneille the Elder, also lingered, contributing to a rich blend of native and foreign traditions.

The Indispensable Roman Sojourn

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Michel Corneille the Younger understood the profound importance of a journey to Italy, particularly Rome, the cradle of classical antiquity and Renaissance mastery. He traveled there to immerse himself in the works of the great masters. In Rome, he diligently studied the art of the Carracci family – Annibale (1560–1609), Agostino (1557–1602), and Ludovico (1555–1619) – whose Bolognese academy had revitalized painting by emphasizing drawing from life and a return to classical principles.

The influence of Domenichino (1581–1641), a prominent pupil of the Carracci, is also evident in Corneille's work, particularly in the clarity of his compositions and the expressive gravity of his figures. While in Rome, he would also have deepened his understanding of Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520), whose harmonious compositions and idealized figures remained a benchmark for academic art. Furthermore, the towering presence of Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), a Frenchman who spent most of his career in Rome and became a paragon of classical landscape and history painting, would have been an undeniable influence, shaping Corneille's approach to narrative clarity and intellectual rigor. Even the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio (1571–1610), though perhaps less directly emulated in Corneille's more classical temperament, contributed to the rich artistic vocabulary available to artists studying in Italy.

This period of study in Italy was transformative, refining his technique and broadening his artistic horizons. He absorbed the lessons of Italian High Renaissance and Baroque art, which he would later synthesize with the French classical tradition upon his return to Paris.

Ascent within the Académie Royale and Royal Favor

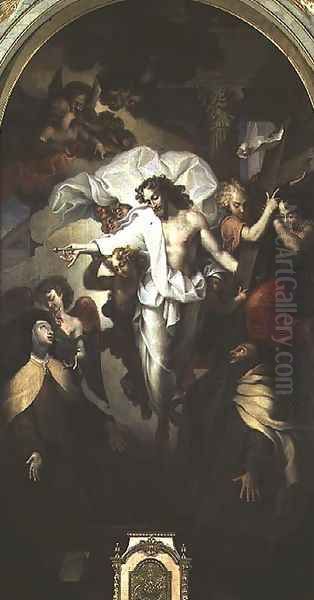

Upon his return to Paris, Michel Corneille the Younger quickly established himself. In 1663, at the young age of twenty-one, he was received into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. His reception piece, a significant work demonstrating his skill and adherence to academic ideals, was Our Lord’s Appearance to St. Peter after His Resurrection. This painting, likely showcasing his mastery of historical narrative, anatomical precision, and dignified emotion, secured his place among the recognized artists of the kingdom.

His career within the Académie progressed steadily. In 1673, he was appointed an adjunct professor, a role that involved teaching and guiding younger artists. His dedication and skill were further recognized in 1690 when he was promoted to the position of full professor. This academic career ran parallel to his active practice as a painter, undertaking significant commissions.

Corneille's talents did not go unnoticed by the Crown. He was favored by King Louis XIV and received numerous commissions to decorate royal residences and important religious edifices. He contributed to the vast decorative programs at the Palace of Versailles, the ultimate expression of Louis XIV's power and artistic patronage, working alongside a legion of artists under the direction of Charles Le Brun. He also executed works for the royal châteaux of Meudon and Fontainebleau. His religious paintings adorned several Parisian churches, including the Cathedral of Notre-Dame and the church of the Invalides (specifically, the Chapel of Saint Gregory). These commissions often involved large-scale frescoes and altarpieces, demanding not only artistic skill but also the ability to manage complex projects and work within grand architectural settings.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Michel Corneille the Younger's artistic style is characterized by a blend of French classicism and Italianate influences, particularly those of the Bolognese school. His paintings, primarily historical and religious subjects, demonstrate a precise drawing technique, a concern for anatomical accuracy, and a dignified, often solemn, portrayal of human emotion. His compositions are generally harmonious and well-balanced, reflecting the academic ideals of clarity and order.

There is a discernible influence from the Carracci and their followers, such as Domenichino, in the way he structured his narratives and rendered his figures. His coloration, while perhaps altered by time in some surviving works, was considered refined and pleasing by his contemporaries. Hints of the Venetian school's approach to color and light can also be detected in some of his works, suggesting a broad appreciation for various Italian traditions.

While working within the dominant classical framework championed by Le Brun, Corneille's style retained a degree of individual character. He was less rigidly doctrinaire than some of his contemporaries, and his work, particularly his etchings, could display a "free and bold" quality. This suggests a capacity for expressive dynamism alongside academic discipline. His figures, while idealized, often convey a sense of gravitas and psychological presence. The influence of his teacher Pierre Mignard might be seen in a certain elegance and a softer, more painterly touch compared to the sometimes sterner classicism of Le Brun's direct followers.

Later in his career, some art historians note a stylistic evolution, with his work showing an engagement with what has been termed post-Raphaelite trends and even elements of Italian "decadent" art, suggesting a continued exploration and adaptation of artistic currents throughout his life. This adaptability, while rooted in a strong classical foundation, marks him as an artist responsive to the evolving tastes of his time.

Mastery in Etching and Engraving

Beyond his significant output as a painter, Michel Corneille the Younger was a prolific and accomplished etcher and engraver. He is credited with producing over one hundred etchings, a testament to his dedication to this medium. His prints often reproduced his own painted compositions or those of other masters, but many were original designs conceived specifically for the medium.

His style in etching was often described as "free and bold," indicating a lively and expressive use of line, less constrained than the more formal demands of large-scale history painting. This freedom allowed for a more personal and immediate artistic statement. Notable examples of his graphic work include The Virgin Suckling the Infant Jesus and Abraham journeying with Lot. These prints, like his paintings, often depicted religious or mythological scenes, making his work accessible to a wider audience than unique paintings could reach.

His skill in printmaking placed him in the company of other notable French printmakers of the era, such as Sébastien Leclerc (1637–1714) and Robert Nanteuil (1623–1678), though Nanteuil was primarily a portrait engraver. Corneille's contribution to printmaking was significant in disseminating artistic ideas and providing models for other artists and craftsmen. The production of prints was a vital part of the 17th-century art world, serving devotional, educational, and decorative purposes.

The Gobelins Connection and Tapestry Design

A defining aspect of Michel Corneille the Younger's later career was his long association with the Manufacture des Gobelins. This royal manufactory, established by Jean-Baptiste Colbert under Louis XIV and directed for many years by Charles Le Brun, was a powerhouse of artistic production, renowned for its luxurious tapestries, furniture, and other decorative arts. Artists employed or associated with the Gobelins were among the elite of the French art world.

Corneille lived for many years at the Gobelins, and it was here that he died in 1708. This close connection earned him the distinguishing epithet "Corneille des Gobelins." His role at the manufactory likely involved not only painting but also the creation of cartoons – full-scale preparatory designs – for tapestries. Designing for tapestry required a specific set of skills, including the ability to create compositions that would translate effectively into woven form, considering the texture, color limitations, and collaborative nature of tapestry production.

His work in this area would have brought him into contact with other artists specializing in decorative arts and tapestry design, contributing to the integrated artistic vision that characterized the major projects of Louis XIV's reign. The tapestries produced at Gobelins, based on designs by artists like Le Brun, Corneille, and others such as Jean Jouvenet (1644–1717) or Antoine Coypel (1661–1722), were highly prized diplomatic gifts and adorned royal and aristocratic interiors throughout Europe.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into His Oeuvre

While a comprehensive catalogue of his works is extensive, several paintings and prints stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns.

His Academy reception piece, Our Lord’s Appearance to St. Peter after His Resurrection (1663), was a crucial early demonstration of his abilities in the esteemed genre of history painting.

The Deliverance of St. Peter from Prison is another significant religious painting, a subject popular during the Counter-Reformation, allowing for dramatic lighting and emotional intensity. Such a scene would call upon his skills in depicting divine intervention and human reaction, likely showcasing the influence of Italian masters in handling chiaroscuro and dynamic composition.

Other religious paintings attributed to him include Sainte Madeleine receiving the Stigmata, a subject that allows for the depiction of intense spiritual ecstasy, and A Repose in Egypt, a more tender and intimate scene from the Holy Family's life. The Baptism of Constantine would have been a grand historical subject, requiring a complex multi-figure composition and a sense of imperial solemnity.

His etchings, such as The Virgin Suckling the Infant Jesus and Abraham journeying with Lot, demonstrate his skill in the graphic arts, conveying narrative and emotion through line and tone. Many of his works are preserved in major collections, including the Louvre Museum in Paris and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux (formerly noted as the Bordeaux St. Paul Museum).

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Michel Corneille the Younger operated within a rich and competitive artistic environment. Besides his teachers Le Brun and Mignard, he was a contemporary of many other notable French painters. His brother, Jean-Baptiste Corneille (1649–1695), was also a painter and etcher, and a member of the Académie, sometimes leading to confusion between their works or identities.

Other prominent history painters of his generation or the one immediately following, who were also active in the Académie and royal projects, included Charles de La Fosse (1636–1716), known for his more Rubeniste tendencies and vibrant color; Jean Jouvenet, whose powerful religious scenes were highly regarded; and Antoine Coypel, who also enjoyed significant royal patronage. These artists, while sharing a common grounding in the academic tradition, each developed individual stylistic nuances. The artistic debates of the time, particularly the Poussiniste-Rubeniste controversy (line versus color), animated the discussions within the Académie and influenced the direction of French art. Corneille, with his strong grounding in drawing and Italian classicism, would likely have been more aligned with the Poussiniste camp, though his work was not devoid of painterly qualities.

Anecdotes, Misattributions, and Identity Clarifications

The passage of time and the complexities of artistic families have led to some interesting anecdotes and points of confusion regarding Michel Corneille the Younger.

One notable issue is the occasional confusion with his younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Corneille. Amusingly, Jean-Baptiste was sometimes referred to as "Corneille l'Aîné" (the Elder), despite being the younger sibling, while Michel (the actual elder brother) was "le Jeune" (the Younger), likely to distinguish them from their father, Michel Corneille the Elder. This somewhat counterintuitive naming has occasionally puzzled art historians.

A more significant issue revolves around misattributions. Remarkably, some of Michel Corneille the Younger's works were, at certain points, mistakenly attributed to the great Raphael. It appears that unscrupulous individuals later added Raphael's name to some of Corneille's drawings or paintings, hoping to increase their value. These forgeries were convincing enough to deceive collectors and experts for some time, a testament, ironically, to the quality and classical grace of Corneille's own hand, which could, with alteration, pass for that of the Urbino master. The eventual uncovering of these misattributions highlights the complexities of connoisseurship and the enduring allure of great names.

His long residence and eventual death at the Gobelins manufactory led to his common designation as "Corneille des Gobelins," a useful way to distinguish him from his father and brother, and a marker of his significant association with this important royal institution. There also remains some scholarly discussion about definitively attributing certain works between Michel Corneille the Younger and his father, Michel Corneille the Elder, as is common with artistic families where styles can be closely related.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Michel Corneille the Younger continued to be an active and respected member of the Parisian art world throughout his life. His role as a professor at the Académie Royale ensured his influence on subsequent generations of artists. He spent his final years residing at the Gobelins manufactory, a place central to French artistic production, and died there on August 16, 1708, at the age of sixty-six.

His legacy is that of a skilled and versatile artist who contributed significantly to the religious and decorative painting of the "Grand Siècle." While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary genius of a Poussin or the overarching directorial power of a Le Brun, Corneille was a master craftsman and a learned painter who upheld the high standards of the French classical tradition. His numerous paintings for churches and royal palaces, his dedicated teaching, and his prolific output as an etcher all attest to a productive and influential career.

His works continue to be studied for their embodiment of 17th-century French academic art, their synthesis of Italian and French traditions, and their technical proficiency. They offer valuable insights into the religious piety, historical consciousness, and artistic patronage of one of France's most culturally rich periods. The presence of his works in major museum collections ensures that his contribution to the history of art is not forgotten.

Conclusion: A Dedicated Servant of French Classicism

Michel Corneille the Younger, "des Gobelins," was a quintessential artist of his time – deeply rooted in the academic tradition, profoundly influenced by Italian art, and a significant contributor to the artistic projects that defined the reign of Louis XIV. From his early training under his father and the luminaries Le Brun and Mignard, through his formative studies in Rome, to his esteemed position within the Académie Royale and his long service at the Gobelins, Corneille dedicated his life to the pursuit of art.

His paintings, characterized by their clarity, dignity, and technical skill, adorned churches and royal residences, while his numerous etchings disseminated his artistic vision more widely. Though sometimes entangled in issues of attribution or overshadowed by more famous names, his substantial body of work and his role as an educator secure his place as an important figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century French art. He remains a testament to the enduring power of the classical tradition and the vibrant artistic culture of Paris during the Grand Siècle.