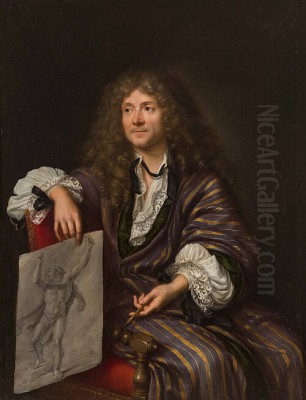

Nicolas Pierre Loir, a distinguished French painter and etcher of the Baroque period, carved a notable niche for himself within the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th-century Paris. His work, characterized by a refined classicism and a delicate sensibility, contributed to the rich tapestry of what is often termed the "Grand Siècle" (Great Century) of French art, flourishing under the reign of King Louis XIV. Though perhaps not as universally renowned today as some of his towering contemporaries, Loir's artistic output, patronage, and academic involvement mark him as a significant figure worthy of detailed exploration.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris in 1624, Nicolas Pierre Loir was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. His family was one of artisans; his father, Nicolas Loir, was a goldsmith, and his brother Alexis Loir would also become a renowned goldsmith and engraver. This familial background in the decorative arts likely instilled in him a meticulous attention to detail and craftsmanship.

His formal artistic training was under the tutelage of Sébastien Bourdon, a highly versatile and influential painter who had himself absorbed diverse influences, including those of Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, as well as the Bamboccianti in Rome. Bourdon's eclectic style, ranging from grand historical and religious scenes to genre paintings and portraits, would have provided Loir with a broad artistic foundation. Under Bourdon, Loir would have honed his skills in drawing, composition, and the classical principles that were increasingly coming to define French art.

The Pivotal Italian Sojourn

Like many ambitious artists of his era, Loir recognized the indispensable value of a journey to Italy, the wellspring of classical antiquity and Renaissance mastery. He undertook this formative trip between 1647 and 1649, spending time primarily in Rome. This period was crucial for his artistic development. In Italy, he would have directly encountered the masterpieces of Raphael, Michelangelo, and other Renaissance giants, as well as the works of contemporary Italian Baroque artists such as Annibale Carracci, Domenichino, and Guido Reni.

However, the most profound influence during his Italian stay, and indeed throughout his career, was that of his compatriot Nicolas Poussin. Poussin, who had established himself as the leading figure of French classicism while residing in Rome, championed an art of intellectual rigor, moral gravity, and harmonious order. Loir deeply absorbed Poussin's principles of composition, his emphasis on clear narrative, and his idealized representation of figures and landscapes. This Poussinian classicism would become a hallmark of Loir's mature style, tempered with his own gentler, more lyrical touch.

Return to Paris and Academic Recognition

Upon his return to Paris around 1649 or 1650, Loir began to establish his career. The artistic scene in Paris was increasingly dominated by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), founded in 1648. This institution, under the powerful direction of Charles Le Brun, aimed to elevate the status of artists and promote a distinctly French classical style in service of the monarchy.

Loir's talent did not go unnoticed. He was recommended by King Louis XIV himself and by Charles Le Brun for admission to the Academy. In 1663, he was formally received (agréé) and then made a full member (reçu) of the Académie Royale. His reception piece, a significant work demonstrating his capabilities, was the allegorical painting Allégorie de la fondation de l'Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Allegory of the Foundation of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). This painting, now housed in the Palace of Versailles, not only showcased his adherence to classical ideals but also his alignment with the cultural ambitions of the French state.

His membership in the Academy brought him prestige and opportunities. He received regular stipends from the King, a testament to the royal favor he enjoyed. Loir was involved in several significant decorative projects for royal residences, including the Tuileries Palace and the Palace of Versailles, often working under the overarching direction of Le Brun. He also contributed to decorative schemes for the Louvre.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Nicolas Pierre Loir's style is best described as a refined and elegant classicism. He shared with Poussin a commitment to clarity of composition, balanced forms, and idealized figures. His drawing was precise, and his color palette, while sometimes rich, often leaned towards cooler, more subdued harmonies, characteristic of the French classical school. Unlike the more dramatic and emotionally charged works of some Italian Baroque artists, Loir's paintings often convey a sense of calm, order, and quiet dignity.

His subject matter was diverse, encompassing religious scenes, mythological subjects, allegories, and occasionally portraits. Religious themes formed a significant part of his oeuvre. He depicted scenes from the Old and New Testaments, often focusing on moments of piety, martyrdom, or divine revelation. These works were imbued with a sense of decorum and spiritual gravity, suitable for both private devotion and church commissions.

Mythological and allegorical subjects allowed Loir to explore classical narratives and personifications, often with a didactic or moralizing intent, aligning with the intellectual currents of the Academy. His figures in these paintings are typically graceful and idealized, set within harmonious, often pastoral, landscapes or classical architectural settings.

While primarily a painter, Loir was also a skilled etcher, producing a number of prints, often after his own designs. These etchings demonstrate his fine draftsmanship and his ability to translate his painterly concerns into the graphic medium.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several key works illustrate Nicolas Pierre Loir's artistic achievements and stylistic tendencies.

His reception piece for the Academy, Allégorie de la fondation de l'Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (1663), is a prime example of his allegorical work. It likely depicts figures representing Painting, Sculpture, and perhaps Architecture, guided by Minerva or a personification of Royal Authority, celebrating the establishment of this crucial artistic institution. Such works were vital for an artist's career, demonstrating their ability to handle complex intellectual themes in a visually compelling classical manner.

A significant number of Loir's paintings focused on the life and deeds of Saint Paul. Among these are Saint Paul rend aveugle le faux prophète Barjesus et convertit le proconsul Sergius (Saint Paul Blinding the False Prophet Elymas and Converting the Proconsul Sergius) from 1650. This work would have showcased his ability to manage a multi-figure composition, convey a dramatic narrative moment, and depict varied human emotions within a classical framework.

Another religious painting, La Lapidation de Saint Étienne (The Stoning of Saint Stephen), dated 1651, would have tackled the theme of martyrdom, a popular subject in Counter-Reformation art. Loir's approach would likely have emphasized the saint's steadfast faith in the face of brutal persecution, rendered with classical restraint rather than overt melodrama.

La Flagellation de saint Paul et Silas (The Flagellation of Saint Paul and Silas), from 1655, continues his exploration of apostolic suffering. Such scenes provided opportunities to depict the heroic endurance of the faithful and the nobility of the human form even in distress, a common theme in classical art.

The painting Saint André joyeux à la vue de son supplice (Saint Andrew Joyfully Greeting the Instrument of his Martyrdom), dated 1665, is reported in some sources to be located in the Cerasi Chapel in Rome. If accurate, this would be a notable instance of a French artist's work in such a prominent Roman location, a chapel already famous for works by Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci. The theme itself, a martyr welcoming his fate, is a powerful expression of Christian devotion.

Another work from 1665, Prophète Agabus annonçant à saint Paul à Jérusalem les souffrances qui l'y attendent (Prophet Agabus Announcing to Saint Paul in Jerusalem the Sufferings Awaiting Him), is listed as being in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. This scene, depicting a prophetic warning, would allow for a poignant interplay of characters and a sense of impending drama.

Also dated 1665 is Les Sagittes de saint Sébastien (The Arrows of Saint Sebastian, or Saint Sebastian Pierced with Arrows), now in the Museo Del Prado, Madrid. Saint Sebastian was a frequently depicted saint, his martyrdom offering a chance to portray the idealized male nude in a context of suffering and faith. Loir's interpretation would likely align with the classical ideal, emphasizing the saint's graceful endurance rather than gruesome detail, possibly influenced by earlier Renaissance and Baroque interpretations by artists like Andrea Mantegna, Titian, or Guido Reni.

His etching, Virgin and Holy Family (created between 1644-1679), now in the collection of the Thomas Thomason Museum (as per provided information, though such a museum is not widely known, perhaps referring to a specific private or university collection, or a misattribution for a more common holding like the British Museum or Bibliothèque Nationale), demonstrates his skill in the graphic arts. Such intimate religious scenes were popular for private devotion and showcased an artist's ability to convey tenderness and piety.

Other works attributed to Loir include The Penitent Magdalene in the Desert at the Musée Bossuet in Meaux, a theme that allowed for the depiction of pathos and devotion, often set within a contemplative landscape. The Musée du Louvre in Paris holds works such as Queen Giving Audience to an Old Man (also known as La reine de Saba or The Queen of Sheba) and Due en addressing soldiers (possibly Queen Addressing Soldiers, also linked to the Queen of Sheba theme), indicating his engagement with historical or Old Testament subjects featuring regal figures and courtly scenes.

Loir's Artistic Milieu: Teachers, Pupils, and Contemporaries

Nicolas Pierre Loir's artistic journey was shaped by his interactions with teachers, pupils, and the broader community of artists in Paris.

His primary teacher, Sébastien Bourdon (1616–1671), was a pivotal figure. Bourdon's own stylistic versatility and his experience in Italy provided a rich learning environment. Bourdon himself was influenced by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), and he passed on this classical inclination.

Loir, in turn, is known to have had pupils, though his workshop may not have been as extensive as some of his contemporaries. One documented student is Pierre Mosnier (or Monier) (1641–1703), who also became a member of the Académie Royale and worked on decorative projects, including at Versailles.

The dominant artistic figure of Loir's mature career was undoubtedly Charles Le Brun (1619–1690). As First Painter to the King and director of the Gobelins Manufactory and the Académie Royale, Le Brun wielded immense influence, shaping the official artistic taste of the era. Loir, like most academicians, would have worked within the artistic framework largely defined by Le Brun, contributing to large-scale royal commissions.

Loir was a contemporary of other significant French classical painters. Eustache Le Sueur (1616–1655), known for his gentle, Raphaelesque classicism and his extensive series of paintings on the life of Saint Bruno, was a key figure in the early years of the Academy. Laurent de La Hyre (1606–1656) developed an elegant and poetic classical style, often depicting religious and mythological scenes with a distinctive clarity and refined sensibility.

Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674), though of Flemish origin, became one of the foremost painters in France, renowned for his austere and psychologically insightful portraits, as well as his deeply religious works influenced by Jansenism. His sober realism offered a distinct strand within French Baroque art.

While Poussin was the primary model for classicism, the influence of earlier French artists who had absorbed Italian Baroque ideas, such as Simon Vouet (1590–1649), was also part of the artistic landscape. Vouet had introduced a lighter, more decorative Baroque style to Paris before the ascendancy of Poussinian classicism.

In the realm of landscape painting, Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), like Poussin, spent most of his career in Rome, creating idealized landscapes that profoundly influenced generations of artists. Though Loir was primarily a figure painter, the classical landscape tradition was an integral part of the artistic environment.

Among Italian artists whose influence permeated the classical tradition Loir inherited were Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) and his pupil Domenichino (1581–1641). Their work in Rome, particularly their emphasis on drawing, idealized forms, and clear composition, laid crucial groundwork for 17th-century classicism. Even the more dramatic art of Caravaggio (1571-1610), though stylistically different, was a powerful force in Rome that all artists visiting would have been aware of.

Loir also worked alongside artists specializing in different genres, such as Jean Tassel (1608-1667), known for his religious paintings and portraits with a distinctive provincial character, and Pierre-Antoine Patel (often referred to as Patel le jeune, 1648-1707), who specialized in classical landscapes with ruins, continuing a tradition established by his father, Pierre Patel.

Later Years and Legacy

Nicolas Pierre Loir continued to work in Paris until his death in 1679. He remained an active member of the artistic community, contributing to the cultural vibrancy of Louis XIV's reign. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as Poussin or Le Brun, his oeuvre represents a significant contribution to French classical painting. His works are characterized by their elegance, technical refinement, and adherence to the intellectual and aesthetic ideals of the Académie Royale.

His paintings and etchings are found today in various museums and collections, primarily in France, including the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Palace of Versailles, and the Musée Bossuet in Meaux. Works attributed to him, like the Saint Sebastian in the Prado, Madrid, and the pieces reportedly in Rome and Jerusalem, attest to a broader, though perhaps less documented, dissemination of his art.

Nicolas Pierre Loir's legacy lies in his embodiment of the French classical tradition. He successfully navigated the academic system and contributed to the major artistic enterprises of his time. His art reflects a period when France was asserting its cultural dominance in Europe, with Paris emerging as a leading artistic center. He was a skilled practitioner of a style that valued harmony, reason, and idealized beauty, leaving behind a body of work that offers a refined and graceful interpretation of the classical ideal during the Grand Siècle. His dedication to the principles of Poussin, combined with his own delicate sensibility, ensures his place among the notable French painters of the 17th century.

It is important to distinguish Nicolas Pierre Loir, the 17th-century painter, from other individuals named Nicolas Loir, notably a modern French cinematographer. The historical painter's career is firmly rooted in the Baroque era, a world of royal patronage, academic structures, and the enduring influence of classical antiquity. His contributions, though sometimes overshadowed by more famous names, were integral to the artistic flourishing of his time.