Moritz Ludwig von Schwind, a prominent figure in the tapestry of 19th-century European art, stands as a quintessential representative of the late Romantic period in the German-speaking world. Born in Vienna on January 21, 1804, and passing away in Niederpöcking, Bavaria, on February 8, 1871, Schwind carved a unique niche for himself as an Austrian painter and illustrator. His legacy is built upon a foundation of lyrical, poetic paintings, often drawing inspiration from folklore, fairy tales, medieval legends, and the rich literary heritage of his time. His works are celebrated for their narrative clarity, gentle humor, and a deeply felt connection to the natural world and the imaginative realms of human storytelling.

Schwind's art emerged during a period of significant cultural and artistic transition. The Enlightenment's emphasis on reason was giving way to Romanticism's embrace of emotion, individualism, and the sublime beauty of nature and the past. In the visual arts, this manifested in a departure from the strictures of Neoclassicism towards more expressive, imaginative, and often nationalistic themes. Schwind became a master at translating these Romantic sensibilities into visual form, creating a body of work that continues to enchant and inspire.

Early Life and Viennese Foundations

Moritz von Schwind's artistic journey began in Vienna, the vibrant capital of the Austrian Empire, a city teeming with cultural and intellectual energy. His early inclinations towards art were nurtured, and in 1821, he formally enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Here, he came under the tutelage of notable artists who would shape his foundational skills and artistic outlook.

Among his influential teachers were Johann Peter Krafft and Ludwig Ferdinand Schnorr von Carolsfeld. Krafft, known for his historical paintings and portraits, would have instilled in Schwind a strong sense of narrative composition and an appreciation for historical subjects. Schnorr von Carolsfeld, himself a significant figure in the Romantic movement and closely associated with the Nazarene artists, likely exposed Schwind to the ideals of reviving spiritual and national themes in art, emphasizing clear lines and heartfelt expression. This early training provided Schwind with a solid grounding in academic technique while simultaneously opening doors to the burgeoning Romantic ethos.

During these formative years in Vienna, Schwind also moved in a circle of creative young men that included the composer Franz Schubert. This friendship was particularly significant. Schwind was deeply moved by Schubert's lieder, and the lyrical, narrative quality of Schubert's music found a visual echo in Schwind's later paintings. He even created illustrations for some of Schubert's songs, demonstrating an early intermingling of musical and visual arts that would remain a characteristic of his work. This period was crucial for developing his romantic sensibilities, his love for storytelling, and his connection to German and Austrian cultural traditions. The atmosphere of Vienna, with its rich musical life and burgeoning Biedermeier culture focusing on domesticity and sentiment, also left an indelible mark on the young artist.

The Munich Years and Artistic Maturation

In 1828, seeking broader artistic opportunities and a more stimulating environment for his Romantic inclinations, Moritz von Schwind relocated to Munich. The Bavarian capital, under the patronage of King Ludwig I, was rapidly becoming a major art center in Germany, attracting artists from all over the German-speaking lands. This move proved to be a pivotal moment in Schwind's career.

In Munich, he came into contact with Peter von Cornelius, one of the leading figures of the Nazarene movement and a dominant force in the Munich art scene. Cornelius, who was overseeing monumental fresco projects, recognized Schwind's talent. Although Schwind's style was more lyrical and less austerely monumental than that of Cornelius, he benefited from the older master's guidance and the intellectual ferment of his circle. This period saw Schwind further hone his skills, particularly in large-scale composition and fresco painting, a medium highly favored for public and royal commissions at the time.

A significant commission came in 1834 when King Ludwig I entrusted Schwind with the task of decorating rooms in the newly built Royal Palace (Königsbau) with frescoes. For this project, Schwind chose to depict scenes from the poems of Ludwig Tieck, a leading German Romantic writer. These frescoes, with their poetic themes and narrative grace, helped to establish Schwind's reputation as a painter capable of translating literary Romanticism into compelling visual art. His work in Munich also included numerous illustrations for books and almanacs, which further disseminated his style and themes to a wider public. He became known for his charming and imaginative depictions of German legends and fairy tales, a genre in which he would become a preeminent master. Other artists active in Munich at the time, such as Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (his former teacher's son, with whom he maintained a friendship) and Carl Rottmann, known for his heroic landscapes, contributed to the city's dynamic artistic environment.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

Moritz von Schwind's artistic style is firmly rooted in German Romanticism, yet it possesses a distinct individuality characterized by its lyrical charm, narrative clarity, and often, a gentle, whimsical humor. He eschewed the dramatic intensity of some Romantics like Caspar David Friedrich or the overt classicism that still lingered, preferring instead a more accessible and poetic mode of expression.

A hallmark of Schwind's work is its strong narrative component. He was a storyteller in paint, drawing his subjects from a wide array of sources: German folk tales (collected by the Brothers Grimm), medieval legends of chivalry and romance, the poetry of Goethe, Tieck, and other Romantic writers, and the world of music. His compositions are typically well-ordered, with figures rendered with a delicate precision and a keen observation of gesture and expression that effectively conveys the story's emotional content.

Color in Schwind's paintings is often bright and harmonious, contributing to the overall idyllic and sometimes dreamlike quality of his scenes. He had a particular fondness for depicting lush, detailed landscapes, often imbued with a sense of enchantment, which serve as fitting backdrops for his fairy-tale characters and legendary heroes. These landscapes, while idealized, often show a careful observation of nature, reflecting the Romantic reverence for the natural world.

The influence of music is palpable in many of his works, not just in direct depictions of musical scenes or illustrations for songs, but in the rhythmic flow of his compositions and the lyrical mood they evoke. His friendship with Schubert undoubtedly deepened this connection. Furthermore, the Nazarene emphasis on clear outlines and heartfelt sentiment, absorbed through his teachers and contemporaries like Peter von Cornelius and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, is evident, though Schwind adapted these principles to his own more playful and less overtly religious themes. He shared with artists like Ludwig Richter a love for the German homeland and its traditions, often infusing his work with a Biedermeier sensibility that celebrated domesticity and simple virtues, albeit within a more fantastical framework.

Masterpieces and Representative Works

Moritz von Schwind's oeuvre is rich with memorable paintings and illustrations that exemplify his unique artistic vision. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his style and thematic concerns.

One of his most celebrated achievements is the fresco cycle, "The Singers' Contest at Wartburg Castle" (Sängerkrieg auf der Wartburg), executed in the Wartburg castle itself between 1853 and 1855. These monumental paintings depict the legendary 13th-century contest of minnesingers. Schwind masterfully brought the medieval tale to life with vibrant characters, rich historical detail, and a palpable sense of drama and romance. This commission was a high point in his career, allowing him to work on a grand scale with a subject perfectly suited to his Romantic inclinations.

The "Cinderella" (Aschenbrödel) series is another cornerstone of his fame. Rather than a single painting, Schwind conceived a cycle of scenes that narrate the beloved fairy tale. He innovatively combined elements from different versions of the story, and even wove in motifs from other tales like Cupid and Psyche, creating a rich, multi-layered visual narrative. These works, known for their charm, detailed settings, and expressive figures, were immensely popular and helped to solidify Schwind's reputation as the preeminent painter of German fairy tales. The series was widely disseminated through reproductions, influencing subsequent fairy tale illustration.

"The Seven Ravens and the Faithful Sister" (Von sieben Raben und der treuen Schwester), exhibited in 1858, is another iconic fairy tale painting. It depicts the poignant story of a sister's quest to save her enchanted brothers. The painting is notable for its intricate composition, its blend of the magical and the human, and its evocative atmosphere. Its success at the German Art Exhibition further cemented his status.

Other significant works include "The Rose, or The Artist's Journey" (Die Rose, oder Die Künstlerwanderung), a complex allegorical painting that reflects on the life and aspirations of an artist, filled with symbolic figures and romantic landscapes. "Dawn Farewell" (Abschied im Morgenrot or Guten Morgen, Schwanengesang) captures a tender, poetic moment, characteristic of his lyrical sensibility. "Forest Chapel" (Waldkapelle) showcases his ability to create atmospheric, nature-infused scenes with a touch of spiritual reverence. His painting often titled "Symphony" visually interprets the power and emotion of music, featuring musicians and singers in an idealized setting, reflecting his deep connection to the musical arts. These works, among many others, demonstrate the breadth of his thematic interests and the consistent charm and technical skill of his artistic execution.

Collaborations, Friendships, and Artistic Circle

Throughout his career, Moritz von Schwind was not an isolated figure but an artist who thrived within a network of friendships and professional collaborations. These relationships enriched his personal life and often had a direct impact on his artistic output and career trajectory.

His youthful friendship with the composer Franz Schubert in Vienna was profoundly influential. Schwind's deep appreciation for Schubert's music is well-documented, and he created illustrations for Schubert's lieder, including the famous "Erlkönig." This early immersion in the world of music and poetry shaped his narrative and lyrical approach to painting. Even after Schubert's early death, Schwind continued to champion his friend's music and often incorporated musical themes into his art. One anecdote tells of Schwind, finding Schubert creatively blocked, sitting down to draw music staves for him, helping the composer to continue his work.

In Munich, his association with Peter von Cornelius was crucial for his development as a fresco painter and for securing important commissions. While their artistic temperaments differed, Cornelius recognized Schwind's talent and provided mentorship. He also maintained a close friendship with Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, whom he had known from Vienna. They were part of the same artistic milieu in Munich, sharing Romantic ideals. It's noted they may have collaborated or at least discussed designs for projects like the stained glass windows of Copenhagen Cathedral.

The writer Franz Grillparzer, a leading Austrian literary figure, was another important friend. Grillparzer recognized Schwind's potential and reportedly encouraged his move to Munich, seeing it as a city where his talents could flourish. This connection highlights Schwind's integration into the broader cultural landscape, bridging visual art and literature.

Schwind also collaborated directly with other artists on specific projects. For instance, he worked with Ludwig Mohn on illustrations for "Aschenbrödel" (Cinderella), indicating a practical engagement with the production and dissemination of illustrated works. These collaborations, whether formal or informal, underscore the interconnectedness of the Romantic art world, where painters, musicians, and writers often inspired and supported one another. His circle would have also included other Munich-based artists like the Biedermeier painter Carl Spitzweg, or landscape artists like Carl Rottmann, even if their primary subjects differed, they were part of the same artistic ecosystem fostered by King Ludwig I.

Teaching, Influence, and Legacy

Moritz von Schwind's impact extended beyond his own prolific output; he also played a role as an educator and left a lasting influence on subsequent generations of artists, particularly in the realm of Romantic illustration and fairy tale depiction.

From 1847, Schwind held a professorship at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, a prestigious position that allowed him to impart his knowledge and artistic philosophy to students. While specific names of many of his students are not always prominently recorded in broad art historical surveys, it is known that his pupils were involved in assisting him with large-scale projects, such as the frescoes for Hohenzollern Castle. Through his teaching, he would have disseminated his approach to narrative painting, his emphasis on German folklore, and his lyrical style.

His influence was significantly amplified by the widespread reproduction of his works, especially his illustrations and fairy tale scenes. Engravings and lithographs after his paintings and drawings made his imagery accessible to a broad public, shaping popular conceptions of German fairy tales and legends. In this, he can be seen as a precursor to later great illustrators of fantasy and fairy tales, such as Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, who, though working in a different era and style, inherited the tradition of bringing imaginative worlds to visual life.

Schwind is considered a key figure in the later phase of German Romanticism, successfully translating its ideals into a popular and enduring visual language. He, along with artists like Ludwig Richter, helped to define a particularly German strand of Romantic art that celebrated national heritage, folklore, and a poetic sensibility. His ability to blend heartfelt emotion with technical skill and narrative clarity ensured his appeal. Even artists who pursued different paths, such as the realist Wilhelm Leibl who also taught in Munich later, would have been aware of Schwind's significant presence in the city's art scene.

His dedication to themes from German culture resonated with the burgeoning sense of national identity in the 19th century. The art historian Hermann Grimm (son of Wilhelm Grimm of the Brothers Grimm) was an admirer, highlighting the connection between Schwind's art and the literary sources he so masterfully interpreted. Schwind's legacy, therefore, lies not only in his beautiful paintings but also in his contribution to the cultural iconography of the German-speaking world.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

Beyond his formal artistic achievements, anecdotes and personal details offer a fuller picture of Moritz von Schwind as an individual, revealing his personality, his passions, and his approach to life and art.

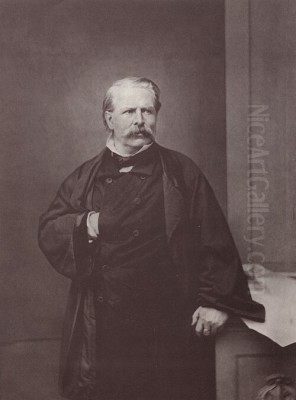

His humor and capacity for self-deprecation are often noted. One example is a self-portrait where he depicted himself as a beardless middle-aged man, possibly with a touch of irony regarding his own appearance or artistic persona. He also humorously commented on his limitations in religious painting, suggesting a self-awareness and a preference for the worldly and fantastical themes where he excelled. His creation of the "Cat Symphony" (Katzensymphonie), a humorous drawing depicting cats in various musical activities, showcases his playful side and his enduring connection to music, even in a whimsical form.

Schwind's deep love for nature was evident not only in his paintings but also in his personal life. He built a country villa, which he named "Tannen" (Firs), on the shores of Lake Starnberg near Munich. He spent his summers there, finding inspiration in the serene landscape and likely creating many sketches and studies from nature. This retreat provided a contrast to the demands of his public commissions and academic duties.

He was also described as having a keen sense of the art market. The strategic exhibition of his "Seven Ravens" series at a major German art exhibition in 1858, where it was highly acclaimed and acquired for a public collection, demonstrates his understanding of how to promote his work and secure his reputation. This suggests a practical side to the romantic artist.

His early life in Vienna was reportedly somewhat bohemian, and like many young artists, he may have faced financial challenges. However, his talent and perseverance eventually led to significant recognition and success. These glimpses into his character reveal a man of warmth, humor, and a profound connection to the imaginative and natural worlds, qualities that are abundantly reflected in his art.

Later Years, Declining Health, and Death

The later period of Moritz von Schwind's life saw continued artistic activity, though it was increasingly affected by declining health. Despite these challenges, he remained dedicated to his craft and continued to undertake significant projects and fulfill his teaching responsibilities.

His eyesight began to fail in his later years, a particularly cruel affliction for a visual artist renowned for his detailed and delicate work. Nevertheless, he persevered, completing important commissions for frescoes and church decorations. His reputation was firmly established, and he was a respected elder statesman of the German art world. He continued to teach at the Munich Academy, influencing a new generation of artists even as his own physical capacities waned.

Moritz von Schwind passed away on February 8, 1871, in Niederpöcking, Bavaria, near his beloved country home on Lake Starnberg. His death marked the end of an era for German Romantic painting. He left behind a rich legacy of works that had captured the imagination of his contemporaries and would continue to be cherished for their poetic beauty and narrative charm. His contributions were recognized with a noble title, "von Schwind," elevating his social standing in acknowledgment of his artistic achievements.

His works found permanent homes in major museums and galleries across Germany and Austria, including the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, and the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, ensuring their accessibility for future generations. The enduring appeal of his art speaks to his success in creating a visual world that, while rooted in the specific cultural context of 19th-century Romanticism, possesses a timeless quality.

Art Historical Significance and Enduring Appeal

Moritz von Schwind holds a significant and secure place in the annals of art history, particularly within the context of 19th-century German and Austrian Romanticism. His contributions were multifaceted, ranging from pioneering new thematic territories to influencing popular visual culture.

He is widely regarded as one of the foremost painters of German fairy tales and legends. His ability to translate these stories into enchanting and accessible visual narratives was unparalleled in his time. Works like the "Cinderella" cycle effectively established a visual canon for these tales, influencing countless illustrators and shaping public perception of these beloved stories for generations. He brought a level of artistic sophistication and emotional depth to subjects that were previously considered more the domain of popular illustration than high art.

As a late Romantic, Schwind masterfully captured the movement's emphasis on emotion, imagination, and the poetic. His lyrical style, characterized by graceful lines, harmonious colors, and a gentle sentimentality, offered a distinct alternative to the more dramatic or heroic modes of Romanticism practiced by artists like Eugène Delacroix in France or even some of his German contemporaries. Schwind's Romanticism was more intimate, often tinged with a Biedermeier sensibility that valued domesticity and heartfelt emotion.

His versatility as an artist—excelling in oil painting, fresco, drawing, and illustration—allowed him to reach a wide audience and work in diverse contexts, from monumental public art to intimate book illustrations. The fusion of art, literature, and music in his work was a hallmark of the Romantic era, and Schwind was a particularly adept practitioner of this interdisciplinary approach. His close ties to figures like Schubert and his frequent drawing upon literary sources underscore this aspect of his art.

While some later critics, particularly those championing modernism, might have viewed his art as overly sentimental or illustrative, recent art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized the innovation and skill inherent in his work, as well as his importance in reflecting and shaping the cultural values of his time. His influence on the visual culture of the German-speaking world was profound, and his paintings continue to be admired for their technical finesse, their imaginative power, and their enduring, gentle charm. He remains a beloved figure, a "poet in paint" whose works offer a delightful escape into realms of magic, romance, and timeless storytelling.