Ivar Arosenius (1878-1909) stands as one of Sweden's most unique and poignant artistic figures. A painter and illustrator whose life was tragically cut short, he left behind a body of work characterized by its blend of fairy-tale whimsy, dark humor, symbolic depth, and profound personal introspection. Operating primarily in watercolor, Arosenius crafted a distinct visual language that explored the eternal themes of life, death, love, and the complexities of the human condition, securing his place as a significant, albeit melancholic, star in the constellation of Nordic art at the turn of the 20th century.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Gothenburg, Sweden, on October 8, 1878, Ivar Axel Henrik Arosenius grew up in a relatively comfortable bourgeois environment. His initial artistic inclinations led him to the Valand Academy (Valands Målarskola) in his hometown in 1896. This was a period of significant artistic ferment in Sweden, with movements like National Romanticism still holding sway, while new Symbolist and proto-Modernist ideas were beginning to circulate. At Valand, he formed a crucial friendship with the Danish sculptor Gerhard Henning, a relationship that would be both supportive and complex throughout their lives.

Arosenius, however, quickly grew restless with the formal training offered at Valand. Seeking different avenues, he briefly attended the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna) in Stockholm in 1898. Yet, academic constraints chafed against his burgeoning individualistic spirit. He found the teaching methods rigid and uninspiring, a sentiment shared by many progressive artists of his generation who felt the Academy was out of touch with contemporary European art movements.

His quest for a more suitable environment led him, from 1899 to 1901, to the Artists' Association School (Konstnärsförbundets skola) in Stockholm. This institution, founded by artists like Richard Bergh and Karl Nordström in opposition to the Academy, offered a more liberal atmosphere. Here, Arosenius encountered fellow students who would become key figures in Swedish Modernism, including Isaac Grünewald. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to new ideas and reinforcing his move away from academic naturalism towards a more personal, expressive style.

The Bohemian Spirit and European Exposure

Returning to Gothenburg, Arosenius became a central figure in the city's burgeoning bohemian circles. Alongside friends like Gerhard Henning and the painter Ole Kruse, he embraced a lifestyle that defied bourgeois conventions. This period was marked by intense artistic discussion, camaraderie, and a certain degree of hedonistic indulgence, which unfortunately contributed to his already fragile health. This bohemian milieu provided both subject matter and a supportive, if sometimes turbulent, environment for his art.

Around 1903, Arosenius embarked on travels across Europe, seeking broader artistic horizons. He spent time in Munich, a vibrant art center known for its Secession movement and publications like Jugend and Simplicissimus, whose graphic styles likely resonated with his own illustrative tendencies. He also visited Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world, where he would have encountered the lingering influences of Symbolism (like Odilon Redon), Post-Impressionism, and the nascent Fauvist movement. A stay in Normandy followed.

These travels exposed him to a wider range of artistic expressions and likely solidified his commitment to his own unique path, distinct from both staid academicism and the dominant trends he observed. He participated in exhibitions, including one at the Konstnärsocietet (Artists' Society) in Stockholm, gaining some recognition, though widespread fame remained elusive during his lifetime. His experiences abroad enriched his visual vocabulary but ultimately reinforced his deeply personal and often introspective artistic vision.

Artistic Style: Watercolor, Whimsy, and Melancholy

Arosenius worked predominantly in watercolor, a medium he mastered with exceptional skill. His paintings are often small in scale, inviting intimate viewing. He developed a distinctive style characterized by fluid lines, often outlined in ink, and a rich, jewel-like color palette. While capable of delicate washes, he frequently employed bold, saturated colors that contribute to the dreamlike or fantastical quality of his imagery. His compositions often feature flattened perspectives and decorative patterning, showing affinities with Art Nouveau and perhaps the influence of Japanese prints, which were popular among European artists at the time.

A defining characteristic of Arosenius's art is its unique emotional tone. He masterfully blended humor, often dark or satirical, with an underlying sense of melancholy and an awareness of life's fragility. Fairy tales, folklore, and biblical stories provided frequent inspiration, but he imbued these traditional narratives with his own psychological interpretations and contemporary relevance. His work often possesses a narrative quality, hinting at stories unfolding just beyond the frame.

His style shows an affinity with the spirit, if not always the direct visual language, of Symbolism. Like Symbolist painters such as Gustave Moreau or Arnold Böcklin, Arosenius prioritized subjective experience, emotion, and ideas over objective representation. However, his approach was less grandiose and often more intimate and idiosyncratic, infused with a specifically Nordic sensibility and a touch of the grotesque or absurd. The influence of the 18th-century Swedish poet and songwriter Carl Michael Bellman, known for his vivid, often bawdy, depictions of Stockholm life, can be detected in Arosenius's blend of earthiness and poetic feeling.

Themes: Domesticity, Death, and the Human Comedy

The thematic range of Arosenius's work is remarkably broad for such a short career. A central duality exists between depictions of cozy domesticity and explorations of darker, existential themes. After his marriage to Eva Adler in 1906 and the birth of their daughter Eva, affectionately known as Lillan, in 1907, his art increasingly focused on intimate family scenes. These works often portray moments of tenderness and everyday life, yet even here, a subtle undercurrent of vulnerability or strangeness can sometimes be felt.

Conversely, Arosenius constantly grappled with the themes of life, death, good, and evil. His lifelong struggle with hemophilia, a genetic bleeding disorder, cast a long shadow over his existence and undoubtedly fueled his preoccupation with mortality. Death appears frequently in his work, sometimes personified as a skeletal figure, other times alluded to more symbolically. This wasn't merely morbid fascination; it was an artist confronting his own precarious reality with honesty, sometimes defiance, and often a surprising degree of dark humor.

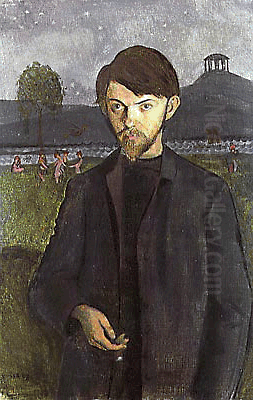

He explored biblical narratives, classical myths, and folk legends, often using them as vehicles for commentary on human nature. The Seven Deadly Sins, particularly lust, were recurring subjects, depicted with a mixture of satirical critique and frank acknowledgment of human desires. Works like The Tree of Life suggest a critique of modern materialism and a yearning for simpler, perhaps more spiritual, values. Self-portraits are numerous and revealing, showing the artist in various guises – contemplative, defiant, comical, or resigned – offering a poignant chronicle of his inner life.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Arosenius's World

Among Arosenius's most celebrated works is the picture book Kattresan (The Cat Journey), created for his daughter Lillan and published posthumously in 1909. This charming and imaginative tale, told through vibrant watercolors, follows Lillan and her cat on a fantastical adventure. It has become a classic of Swedish children's literature, beloved for its whimsical illustrations and gentle narrative. Yet, even in this delightful work, some critics detect subtle hints of the artist's characteristic melancholy.

Flickan vid ljuset (The Girl and the Candle, 1907) is another iconic image, depicting a young girl (likely Lillan) mesmerized by a candle flame in a darkened room. The painting captures a sense of childhood wonder but also evokes themes of light and darkness, innocence and the unknown. The simple composition and rich colors create a powerful, almost hypnotic effect.

Det brustna hjärtat (The Broken Heart) explores themes of love and loss with poignant simplicity. His self-portraits, such as the one where he depicts himself as a Pierrot figure or confronts death, are powerful statements about his identity and mortality. Works inspired by folklore and legend, like Sankt Göran och draken (Saint George and the Dragon) or Kalifens guldgås (often translated similarly to The Caliph's Golden Bird, though 'gås' means goose), showcase his ability to reinterpret traditional stories through his unique lens, often emphasizing the fantastical or grotesque elements.

His portraits of friends and family, including his wife Eva, are rendered with warmth and psychological insight, often tinged with his signature blend of affection and gentle irony. These works demonstrate his skill in capturing individual character while maintaining his distinct stylistic approach. Each piece, whether a simple domestic scene or a complex allegorical composition, contributes to the rich tapestry of his artistic universe.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Ivar Arosenius operated within a dynamic period in Swedish and European art. While developing his highly personal style, he was aware of and interacted with various artistic currents and figures. His closest associates in Gothenburg were the aforementioned Gerhard Henning and Ole Kruse, forming a core part of the city's bohemian scene. Their shared interest in Symbolism and expressive forms created a mutually stimulating environment, even amidst personal tensions.

In Stockholm, at the Konstnärsförbundets skola, he brushed shoulders with the generation that would spearhead Swedish Modernism, like Isaac Grünewald and possibly Leander Engström, though Arosenius's path remained distinct from the more radical colorism of the emerging Expressionists. He existed somewhat apart from the established masters of the previous generation, such as Anders Zorn, renowned for his society portraits and depictions of rural life, and Carl Larsson, whose idyllic portrayals of family life offered a stark contrast to Arosenius's often darker or more complex view of domesticity.

While not directly part of the National Romantic landscape movement associated with figures like Prince Eugen or Karl Nordström, Arosenius shared with them a connection to Swedish culture and folklore, albeit interpreted through a more psychological and symbolic filter. He admired earlier Swedish artists like Ernst Josephson, whose own struggles with mental health and visionary works perhaps resonated with Arosenius's exploration of inner worlds. The stark urban nocturnes of Eugène Jansson ("The Blue Painter") represent another facet of contemporary Swedish art, focusing on different themes but sharing a mood of introspection.

Internationally, the influence of Edvard Munch is palpable, particularly in the shared preoccupation with themes of death, anxiety, and psychological states, though Arosenius's style is generally less raw and more illustrative. The linear elegance and decadent sensibility of Aubrey Beardsley might also be seen as a kindred spirit, especially in Arosenius's ink work. Comparisons can also be drawn to other Nordic contemporaries exploring symbolism and national identity, such as Finland's Akseli Gallen-Kallela or Denmark's Vilhelm Hammershøi, though each had a distinct focus. Arosenius's unique blend of influences and personal vision set him apart even within this rich context. His interaction with the writer August Strindberg, for whom he reportedly created some illustrations, further connects him to the broader cultural landscape of the era.

Illness, Later Years, and Untimely Death

The final years of Arosenius's life were marked by a flowering of creativity centered around his family life in Älvängen, outside Gothenburg, but also by his deteriorating health. His marriage to Eva Adler and the joy brought by their daughter Lillan provided a period of relative domestic stability and inspired some of his most tender and beloved works, including the illustrations for Kattresan. This period saw a shift towards more intimate themes, though the underlying awareness of mortality never fully disappeared.

His hemophilia, however, remained a constant threat. The condition, which impairs the body's ability to control blood clotting, meant that even minor injuries could have serious consequences. Despite his illness, Arosenius lived life with a certain intensity, reflected in both his bohemian earlier years and his dedicated artistic output. His physical fragility stands in poignant contrast to the imaginative vitality of his art.

In late 1908, his health took a decisive turn for the worse. Ivar Arosenius died from complications related to his hemophilia on January 2, 1909, in Älvängen. He was only 30 years old. His death cut short a career that, while brief, had already produced a remarkably rich and distinctive body of work. The loss was deeply felt within the Swedish art community, robbing it of one of its most original talents just as he was reaching artistic maturity.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Although Arosenius achieved some recognition during his lifetime, his reputation grew significantly after his death. The posthumous publication of Kattresan cemented his place in the hearts of the Swedish public and introduced his art to a wider audience. Memorial exhibitions helped to showcase the breadth and depth of his oeuvre, revealing an artist of profound originality and emotional resonance.

Today, Ivar Arosenius is regarded as a major figure in Swedish art history. His works are held in prominent collections, including the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm and the Gothenburg Museum of Art. He is celebrated for his technical mastery of watercolor, his unique blend of humor and melancholy, and his unflinching exploration of universal human themes through a highly personal lens. His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Swedish illustrators and artists drawn to narrative and symbolic modes of expression.

Arosenius stands as a testament to the power of art created under the shadow of mortality. His ability to find beauty, humor, and profound meaning in both the joys of domestic life and the contemplation of death gives his work an enduring power. He crafted a self-contained universe, filled with fantastical creatures, poignant self-portraits, tender family scenes, and dark allegories – a world that continues to captivate and move viewers more than a century after his death. His legacy is that of a unique storyteller in paint, whose brief life yielded a treasure trove of images that speak to the enduring complexities of the human spirit.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Ivar Arosenius remains a compelling figure in the landscape of early 20th-century art. His tragically short life yielded an artistic output of remarkable intensity and originality. He navigated the currents of Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and emerging Modernism, yet forged a path uniquely his own, characterized by technical brilliance in watercolor, a distinctive blend of fairy-tale aesthetics and dark humor, and a profound engagement with the fundamental questions of existence. From the whimsical adventures of Kattresan to the poignant introspection of his self-portraits and the complex allegories exploring life and death, Arosenius created a world that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. His art continues to enchant and provoke, securing his legacy as one of Sweden's most cherished and singular artistic voices.