Edward Frederick Brewtnall (1846–1902) stands as a notable figure in the landscape of late Victorian art, an era teeming with romanticism, a burgeoning interest in folklore, and a deep appreciation for detailed, narrative-driven imagery. Though perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his Pre-Raphaelite predecessors or contemporaries in the Royal Academy, Brewtnall carved a significant niche for himself, particularly as a watercolourist and an illustrator of enchanting, often whimsical, scenes. His body of work, spanning evocative landscapes, keenly observed social vignettes, and captivating fairy tale illustrations, offers a rich window into the artistic sensibilities and cultural preoccupations of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in London on October 13, 1846, Edward Frederick Brewtnall was the son of Edward Brewtnall, who served as the headmaster of the People's College in Warrington. This background, potentially emphasizing education and cultural awareness, may have played a role in the young Brewtnall's artistic inclinations. Around 1868, he made his way to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world, to pursue formal artistic training.

His chosen institution was the Lambeth School of Art, a significant training ground for many aspiring artists and designers of the period. The Lambeth School, under the influence of figures like John Sparkes, was known for its practical approach and its connections to industry, particularly Doulton's pottery. However, it also provided a solid grounding in drawing and painting. It was during this formative period that Brewtnall would have honed his skills in draughtsmanship and begun to explore the watercolour medium that would become his forte. The emphasis on observation and technical proficiency at institutions like Lambeth was crucial for artists aiming to exhibit at the prestigious, and often crowded, London exhibitions.

Gaining Recognition: Exhibitions and Memberships

Brewtnall's professional debut came in 1868 when he exhibited a work titled "Post Time" at the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) in Suffolk Street. The RBA, while perhaps not as prestigious as the Royal Academy, was an important venue for artists, particularly those working outside the academic mainstream or in mediums like watercolour. This initial exhibition marked his entry into the competitive London art scene.

A significant early work that garnered attention was "A Party of Working Men at the National Gallery," exhibited in 1870. This piece suggests an early interest in social observation and genre scenes, depicting ordinary people engaging with high culture. Such subjects were popular in the Victorian era, reflecting both a growing democratic sentiment and a fascination with the lives of different social classes. Artists like William Powell Frith had achieved immense success with sprawling canvases of modern life, such as "Derby Day" or "The Railway Station," and while Brewtnall's work was likely on a more modest scale, it tapped into a similar vein of contemporary social commentary.

Brewtnall's dedication to the watercolour medium was a defining feature of his career. He steadily gained recognition for his skill in this demanding art form, which, by the Victorian era, had achieved a status nearly comparable to oil painting, thanks to pioneers like J.M.W. Turner and the efforts of dedicated watercolour societies. His growing reputation led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS), often referred to as the "Old Watercolour Society," in 1875. This was a significant professional milestone. The RWS was, and remains, a prestigious body, and membership was a mark of distinction. He was further elevated to full membership in 1883, cementing his status as a leading watercolourist of his generation. He also exhibited with the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, indicating his versatility, though watercolour remained his primary focus.

The Allure of the Fantastical: Fairy Tales and Legends

A substantial and perhaps the most enduring part of Brewtnall's oeuvre is dedicated to the world of fairy tales, folklore, and legend. The Victorian era witnessed a profound fascination with such subjects. This interest was fueled by a romantic reaction against industrialization, a nostalgia for a perceived simpler past, and the publication of numerous collections of folk tales, including those by the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, as well as renewed interest in British legends like Arthurian tales.

Brewtnall's "Sleeping Beauty," painted in 1902 and now housed in the Warwickshire Museum, is a prime example of his engagement with this genre. His interpretation likely featured the lush detail, romantic atmosphere, and narrative clarity typical of his style. The story of Sleeping Beauty, with its themes of enchantment, suspended time, and heroic rescue, offered rich visual possibilities that appealed to the Victorian imagination. Artists like Edward Burne-Jones, a leading figure of the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, famously tackled this subject in his "Briar Rose" series, creating dreamlike, melancholic visions. Brewtnall's approach, while sharing a romantic sensibility, might have been more illustrative and less laden with the complex symbolism of Burne-Jones.

Another significant work in this vein is "The Visit to the Witch" (exhibited 1882/1883, also known as "A Visit to the Witch"). This painting, likely depicting a scene of consultation or enchantment, taps into the enduring fascination with magic and the occult. Witches were a recurring motif in Victorian art and literature, often portrayed with a mixture of fear and allure. The subject allowed for dramatic compositions, expressive figures, and the creation of a mysterious, otherworldly atmosphere. One might compare such a theme to the darker, more psychologically intense fairy tale illustrations of artists like Richard Dadd, whose "The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke" is a masterpiece of intricate, obsessive detail, or the slightly later, more whimsical but still eerie, works of John Anster Fitzgerald.

Brewtnall also illustrated "Bluebeard's Wife" (1884) and "Little Red Riding Hood." These classic tales, with their undercurrents of danger and morality, were popular subjects. "Bluebeard's Wife," in particular, offered scope for depicting suspense and psychological drama, focusing on the forbidden chamber and the heroine's perilous curiosity. His illustrations for "Little Red Riding Hood" would have contributed to the visual culture surrounding this universally known story, a subject also tackled by contemporaries like Walter Crane, whose stylized and decorative approach to children's book illustration was highly influential.

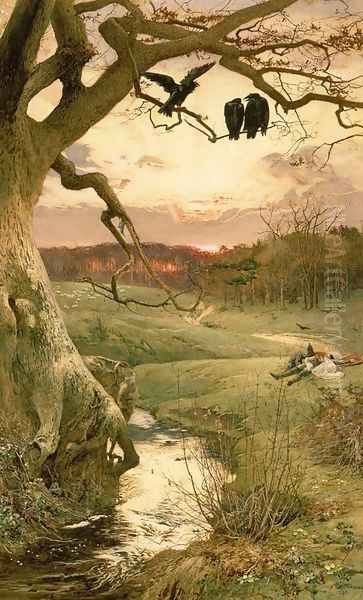

"The Ravens" (1885) and "Outlaws" (exhibited 1885) suggest a leaning towards themes of folklore, medieval romance, or adventure, common in Victorian narrative painting. These titles evoke images of wild landscapes, mysterious figures, and tales of derring-do, perhaps akin to the historical or literary subjects favored by many Royal Academicians.

Capturing Victorian Life: Social Scenes and Leisure

Beyond the realm of fantasy, Brewtnall was an astute observer of contemporary Victorian life. His painting "Afternoon Tea at a Lawn Tennis Club Tournament" (1891), now in the collection of the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum, is a particularly fine example of this aspect of his work. This piece captures a quintessential scene of upper-middle-class leisure. Lawn tennis was a relatively new and increasingly popular sport in the late 19th century, and its social dimension, particularly the opportunities it provided for genteel interaction between the sexes, made it a popular subject.

The painting likely depicts elegantly dressed figures enjoying refreshments amidst the backdrop of a tennis match, showcasing the fashions and social customs of the era. Such works provide valuable historical documentation of social life. In its depiction of polite society and outdoor leisure, it shares thematic similarities with the works of artists like James Tissot, a French painter who spent a significant period in London and became renowned for his stylish portrayals of fashionable Victorian women and social events. However, Brewtnall's medium of watercolour would have lent a different quality to the scene, perhaps lighter and more atmospheric than Tissot's polished oils. The painting is praised for its detailed observation and the lively atmosphere it conveys, serving as a testament to the social rituals and burgeoning sporting culture of late Victorian England.

His earlier work, "A Party of Working Men at the National Gallery" (1870), as mentioned, also falls into this category of social observation, though focusing on a different stratum of society. It highlights the Victorian era's complex attitudes towards class, education, and access to culture.

Landscapes and the Natural World

While perhaps less emphasized than his narrative or fairy tale subjects, Brewtnall also engaged with landscape painting. The Victorian appreciation for nature was profound, influenced by Romantic poets like Wordsworth and artists like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. The detailed observation of the natural world was also a cornerstone of Pre-Raphaelite philosophy, as advocated by John Ruskin.

A work titled "Green and Cool," now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, suggests a focus on the sensory experience of the landscape. Watercolour was an ideal medium for capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in nature, and many Victorian artists, such as Myles Birket Foster, achieved great popularity with their idyllic depictions of the British countryside. Brewtnall's landscapes likely shared this appreciation for natural beauty, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail and evocative use of colour. His time spent living at Orchard House in the village of West Clandon, Surrey (the house is now known as Amberley Cottage), would have provided ample inspiration from the surrounding English countryside.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Edward Frederick Brewtnall's artistic style is generally characterized as romantic and imaginative, with a strong emphasis on narrative. He was particularly skilled in the use of watercolour, a medium he handled with both delicacy and vibrancy. His works are noted for their rich colour palettes and meticulous attention to detail, qualities that align him with the broader currents of Victorian art, particularly the enduring influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Pre-Raphaelite movement, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, advocated for a return to the art of the early Italian Renaissance (before Raphael), emphasizing truth to nature, bright colours, complex compositions, and often, subjects drawn from literature, religion, or medieval romance. Although Brewtnall was of a later generation, the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic had a lasting impact on British art. His detailed rendering of fabrics, foliage, and facial expressions, as well as his choice of literary and fantastical themes, suggests a clear affinity with Pre-Raphaelite principles. One can see echoes of the jewel-like colours and intricate detail found in the works of Millais or the romantic intensity of Rossetti in Brewtnall's approach.

His illustrations, praised for their "vivid colour" and "attention to detail," would have benefited from these Pre-Raphaelite tendencies. The clarity and narrative force required for effective illustration were well served by his precise draughtsmanship and ability to create compelling, readable compositions. Unlike the more stylized or decorative approaches of some contemporary illustrators like Walter Crane or Kate Greenaway, whose work often emphasized pattern and flat planes of colour, Brewtnall's illustrations likely retained a greater degree of naturalism and pictorial depth, akin to traditional easel painting.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Brewtnall operated within a vibrant and diverse artistic milieu. The late Victorian period saw a multiplicity of styles and artistic concerns. The Royal Academy still dominated the official art world, with painters like Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema producing grand historical and classical scenes. Simultaneously, the Aesthetic Movement, championed by artists such as James McNeill Whistler and Albert Moore, emphasized "art for art's sake," focusing on beauty and formal qualities over narrative content.

As a member of the Royal Watercolour Society, Brewtnall would have been in the company of other distinguished watercolourists. Figures like Helen Allingham, known for her charming depictions of rustic cottages and gardens, and the aforementioned Myles Birket Foster, were immensely popular. The society's exhibitions were important events, showcasing the versatility and expressive potential of the watercolour medium.

His engagement with fairy tale and imaginative subjects placed him in a lineage that included earlier Victorian fairy painters like Richard Dadd and John Anster Fitzgerald, and he can be seen as a precursor to the "Golden Age of Illustration" in the early 20th century, which would feature artists like Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, whose fantastical illustrations for children's books became iconic. While Brewtnall's style was perhaps more rooted in traditional Victorian painting than the more stylized Art Nouveau inflections of Rackham or Dulac, he shared their commitment to bringing imaginary worlds to life with conviction and detail.

Later Career, Legacy, and Critical Reception

Edward Frederick Brewtnall continued to exhibit regularly throughout his career, primarily at the RWS, but also at the Royal Academy, the RBA, and other London and provincial galleries. He maintained a consistent output, building a reputation for his charming and skillfully executed works. He passed away in Bedford Park, London, on November 13, 1902.

In terms of critical reception, Brewtnall was generally well-regarded in his lifetime, particularly for his watercolours. His election to full membership of the RWS attests to the esteem in which he was held by his peers. His works were seen as embodying many of the qualities prized in Victorian art: narrative interest, technical skill, and a pleasing aesthetic.

Some modern critiques, as noted in the provided information, have touched upon the romanticized nature of his fairy tale interpretations. For instance, his "Sleeping Beauty" has been discussed in terms of its adaptation of the original tale, with suggestions that it might have incorporated elements from other stories or softened some of the darker aspects present in older versions of the fairy tale. This is not uncommon in Victorian adaptations of folklore, which often sought to present stories in a manner deemed suitable for a contemporary, often family-oriented, audience. The original folk versions of many tales, such as Giambattista Basile's "Sole, Luna, e Talia" (an early version of Sleeping Beauty), contained elements far more disturbing than their later, more sanitized iterations.

Similarly, his depiction of witches in "A Visit to the Witch" could be analyzed through the lens of gender representation, as such subjects often drew on established, sometimes stereotypical, imagery of female power and otherness. However, these interpretations are often applied retrospectively; within its contemporary context, such a work would have been appreciated for its dramatic potential and imaginative power.

The enduring appeal of Brewtnall's work is evidenced by its presence in museum collections and its occasional appearance in popular culture. The reference to his "Sleeping Beauty" being cited by contemporary artist Ignasi Monreal for a Gucci campaign highlights how historical artworks can find new resonance and inspire modern creators, demonstrating the timeless quality of compelling imagery.

Historical Positioning and Conclusion

Edward Frederick Brewtnall occupies a respected place among the many talented artists of the late Victorian period. He was a master of the watercolour medium, using it to create works of considerable charm, detail, and imaginative power. His contributions to fairy tale illustration are particularly noteworthy, reflecting and shaping the Victorian era's deep fascination with folklore and fantasy.

While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or the avant-garde artists who were beginning to emerge at the turn of the century, Brewtnall excelled within the established traditions of British narrative and illustrative art. His paintings of social scenes, like "Afternoon Tea at a Lawn Tennis Club Tournament," offer valuable insights into the leisure activities and social mores of his time, while his landscapes capture the Victorian appreciation for the beauty of the natural world.

His connection to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, with its emphasis on truth to nature, vibrant colour, and literary or imaginative subjects, is evident in his meticulous technique and thematic choices. He successfully navigated the professional art world, achieving recognition through prestigious societies like the Royal Watercolour Society.

Edward Frederick Brewtnall's legacy is that of a skilled and imaginative artist who contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of Victorian visual culture. His works continue to delight viewers with their narrative charm, technical finesse, and evocative portrayal of worlds both real and imagined, securing his position as a distinctive voice in British art of the 19th century. His ability to capture the romantic spirit of his age, whether in a sun-dappled tennis party or an enchanted princess's slumber, ensures that his art remains engaging and historically significant.