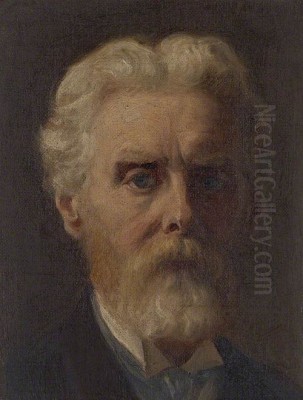

James Archer (1824–1904) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. A proud Scotsman, Archer carved a distinguished career primarily as a painter of historical and literary scenes, alongside sensitive portraits, particularly of children. His work, deeply embedded in the Victorian era's tastes and preoccupations, reflects a meticulous technique, a penchant for narrative, and an engagement with the romantic and moralistic currents of his time. Though perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his English contemporaries, Archer's contributions to Scottish art and his adeptness in capturing the zeitgeist of his age warrant closer examination.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Edinburgh

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1824, James Archer's early life unfolded in a city renowned for its intellectual and cultural vibrancy. He received his initial education at the prestigious Royal High School in Edinburgh, an institution that had nurtured many of Scotland's brightest minds. It was clear from an early stage that Archer possessed a strong artistic inclination, leading him to pursue formal training at the Trustee’s Academy. This institution, later to become the Edinburgh College of Art, was the crucible for many notable Scottish artists.

At the Trustee's Academy, Archer studied under the tutelage of Sir William Allan and Thomas Duncan. Sir William Allan, a distinguished historical painter and President of the Royal Scottish Academy, would have undoubtedly instilled in Archer a respect for grand historical narratives and meticulous research. Thomas Duncan, also a respected painter of historical subjects and portraits, further shaped Archer's developing style. This early training emphasized strong draughtsmanship, compositional skills, and the importance of narrative clarity, all of which would become hallmarks of Archer's mature work. Initially, Archer focused on creating portraits in chalk, a medium that allowed him to hone his skills in capturing likeness and character before fully embracing oil painting.

Rise to Prominence and the Royal Scottish Academy

Archer's talent did not go unnoticed for long. He began exhibiting his work, and his skill quickly garnered recognition within the Scottish art establishment. A pivotal moment in his early career was the exhibition of his chalk drawing, "The Child St John in the Wilderness," at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in 1842, when he was still a very young artist. This was followed by his first oil painting exhibited at the RSA, "The Last Supper," in 1849. This ambitious religious work signaled his growing confidence and technical proficiency in the more demanding medium of oils.

His rising stature was formally acknowledged when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA) in 1850. This was a significant honor, placing him among the ranks of Scotland's most promising artists. His dedication and continued artistic development led to his elevation to the status of full Academician of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in 1858. Membership in the RSA was not merely an honorific; it signified peer recognition and provided a prominent platform for exhibiting his work regularly to a discerning public. Throughout the 1850s, Archer was a consistent contributor to the RSA's annual exhibitions, showcasing a range of subjects that appealed to Victorian sensibilities.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

James Archer's artistic output was characterized by its diversity in subject matter, yet unified by a consistent stylistic approach. He was adept at historical scenes, literary illustrations, religious subjects, and portraiture. His style was marked by careful attention to detail, a rich but controlled palette, and a strong narrative element. He sought to create paintings that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also told a story or conveyed a moral message, aligning with the didactic tendencies prevalent in much Victorian art.

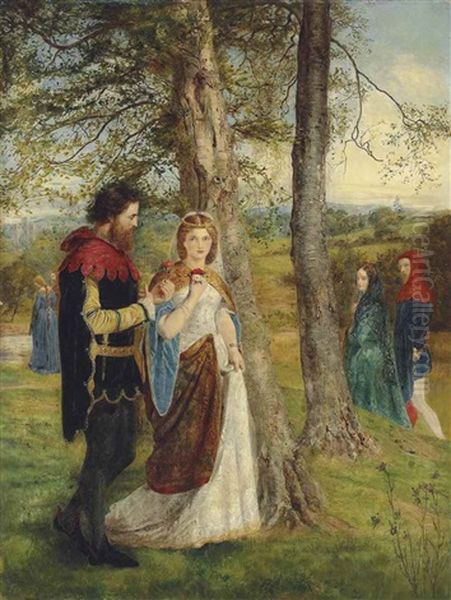

A significant aspect of Archer's oeuvre was his focus on literary themes, particularly scenes from the works of William Shakespeare and the Arthurian legends. The 19th century witnessed a major revival of interest in medieval romance and chivalry, and Arthurian tales, popularized by writers like Alfred, Lord Tennyson, provided rich source material for artists. Archer tapped into this cultural current, producing evocative paintings that brought these legendary figures to life. His depictions were often imbued with a sense of romanticism and drama, capturing key moments from these enduring stories.

Archer also distinguished himself as a pioneer in the portrayal of children. He was one of the first Victorian painters to specialize in creating portraits of children dressed in historical or fanciful costumes. These works were not merely charming likenesses; they often carried an air of nostalgia or whimsy, appealing to the Victorian sentimentality surrounding childhood. His ability to capture the innocence and individuality of his young sitters made these portraits highly sought after. His technical versatility was evident in his proficient use of oils, as well as pencil and chalk for his drawings and studies.

Key Works: Narratives in Paint

Several of James Archer's paintings stand out as particularly representative of his artistic concerns and skills. "The Last Supper" (1849), his first major oil painting exhibited at the RSA, demonstrated his ambition in tackling complex multi-figure compositions and profound religious themes. While adhering to traditional iconography, Archer would have aimed to bring a fresh emotional resonance to this pivotal biblical scene.

His engagement with Arthurian legend is exemplified by works such as "La Morte d'Arthur" (circa 1860s, with a version exhibited in 1897) and "Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere." These paintings captured the drama, romance, and tragedy inherent in Sir Thomas Malory's tales and Tennyson's "Idylls of the King." Archer's interpretations would have focused on the human emotions of the characters, set against meticulously rendered medieval backdrops. For instance, "La Morte d'Arthur" likely depicted the poignant final moments of the legendary king, a subject that resonated with Victorian ideals of heroism and noble sacrifice. Similarly, "Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere" would have explored the complex and ultimately tragic love affair that contributed to the downfall of Camelot, a theme rich in romantic and moral implications.

"Summertime, Gloucestershire" (exhibited 1860) showcases another facet of Archer's work, likely a genre scene or a landscape imbued with a narrative quality. While not as famous as his historical pieces, such works demonstrate his versatility and his ability to capture the atmosphere of a scene. His portraiture, such as the "Portrait of Doctor Joseph Joaquim" (1874), highlights his skill in capturing a sitter's likeness and professional gravitas. This particular portrait was exhibited internationally, first in Philadelphia and later at the Royal Academy in London, indicating its perceived quality. Another notable portrait is "Sir Henry Irving as Mathias in 'The Bells'" (1871-1872), capturing the famous actor in one of his most iconic roles, demonstrating Archer's connection to the theatrical world.

The Influence of Pre-Raphaelitism

James Archer's career coincided with the rise and influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), a group of young English artists—notably William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti—who rebelled against the prevailing academic art standards of the Royal Academy in London. Founded in 1848, the PRB advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colors, and complex compositions found in Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art, before the High Renaissance master Raphael. They emphasized "truth to nature," meticulous detail, and often chose subjects with moral or literary significance.

While Archer was not a formal member of the PRB, his work, particularly from the late 1850s and 1860s, shows a clear affinity with their ideals. His attention to detail, his use of bright, clear colors, and his choice of literary and historical subjects with a strong narrative and emotional content align with Pre-Raphaelite principles. His Scottish contemporary, Noël Paton, with whom Archer was acquainted (Paton was even considered a mentor figure by some accounts), was more directly associated with Pre-Raphaelite circles, as was William Bell Scott. It is likely that Archer absorbed these influences through such connections and through the general artistic discourse of the time.

Archer's Arthurian subjects, for example, were also popular with Pre-Raphaelite artists like Rossetti and William Morris. The emphasis on medieval themes, romantic love, and moral dilemmas found in these legends provided fertile ground for the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. Archer's meticulous rendering of costumes, settings, and natural elements in these paintings echoes the PRB's commitment to detailed observation. However, some critics have noted that Archer's work, while sharing some Pre-Raphaelite characteristics, sometimes leaned more towards a popular Victorian sentimentalism, perhaps lacking the more intense, sometimes unsettling, psychological depth found in the core PRB artists' output. Nevertheless, the Pre-Raphaelite influence is an important context for understanding the development of his style.

London, Exhibitions, and Later Career

By the early 1860s, James Archer had established a solid reputation in Scotland. Seeking broader opportunities and recognition, he moved to London in 1862, the vibrant center of the British art world. He began exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the most prestigious art institution in Britain. His London debut at the Royal Academy was in 1854, even before his permanent move, with chalk portraits titled "Musing" and "Amused." After relocating, he continued to send works, including "In Time of War" (1857, likely exhibited before his move but indicative of his submissions to London).

Living and working in London exposed Archer to a wider range of artistic influences and a larger, more diverse audience. He continued to paint historical scenes, literary subjects, and portraits. His works were generally well-received, appealing to the Victorian taste for narrative painting and skilled craftsmanship. During his career, Archer also undertook travels that broadened his artistic horizons. He is recorded as having visited the United States and India. These journeys would have provided him with new visual experiences and potentially new subject matter, particularly for landscape and figure studies, although specific works directly resulting from these travels are not as widely documented as his historical and literary pieces. His "Portrait of Doctor Joseph Joaquim," exhibited at the Philadelphia International Exhibition in 1874, indicates his presence on an international stage.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

James Archer operated within a bustling and diverse artistic milieu in both Scotland and England. In Scotland, alongside figures like Noël Paton and William Bell Scott, he was part of a generation that sought to define a distinctive Scottish voice within the broader British art scene. Other notable Scottish contemporaries included the landscape painter Horatio McCulloch, known for his dramatic Highland scenes, and history and genre painters like Robert Scott Lauder, who was an influential teacher at the Trustee's Academy. Earlier figures like Sir David Wilkie, with his renowned genre scenes, had already established a strong tradition of Scottish narrative painting.

In London, Archer would have been aware of, and exhibiting alongside, some of the giants of Victorian art. These included William Powell Frith, famous for his panoramic depictions of modern life such as "Derby Day"; Augustus Egg, known for his moralizing narrative series; and George Frederic Watts, a highly respected portraitist and painter of allegorical subjects. The Pre-Raphaelites and their associates, such as John Everett Millais (who later became President of the Royal Academy), Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, and the slightly later Edward Burne-Jones, were also major forces. The art world was also populated by successful academic painters like Sir Edwin Landseer, renowned for his animal paintings, and Sir Francis Grant, a leading portrait painter. Archer's work, with its blend of historical romance, literary illustration, and skilled portraiture, found its niche within this competitive environment. His focus on Arthurian and Shakespearean themes placed him in dialogue with many other artists exploring similar subjects, from the grand historical canvases of Daniel Maclise to the more decorative and symbolic interpretations of the later Pre-Raphaelites.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

James Archer passed away in Haslemere, Surrey, England, in 1904, leaving behind a substantial body of work. In art historical terms, he is primarily remembered as a skilled Scottish painter who successfully navigated the tastes of the Victorian era. His contributions to historical and literary painting, particularly his Arthurian scenes, are significant within the context of the 19th-century revival of interest in medievalism. He captured the romantic spirit of these legends with technical proficiency and a clear narrative sense.

His pioneering work in children's portraiture, especially those featuring costumed figures, marks a distinctive aspect of his career. These portraits are not only charming but also offer insights into Victorian perceptions of childhood and the period's love for theatricality and historical evocation. Archer's dedication to the Royal Scottish Academy and his consistent presence in its exhibitions helped to shape the Scottish art scene of his time. His later career in London and exhibitions at the Royal Academy further solidified his reputation within the broader British art world.

While he may not have achieved the revolutionary impact of the leading Pre-Raphaelites or the widespread fame of some of his English narrative-painting contemporaries, James Archer remains an important representative of Victorian art. His work is characterized by its craftsmanship, its engagement with popular literary and historical themes, and its appeal to the narrative and sentimental inclinations of his audience. His paintings can be found in various public collections, and they continue to be appreciated for their artistic merit and as windows into the cultural landscape of 19th-century Britain. His ability to weave together detailed realism with romantic storytelling ensured his popularity during his lifetime and secures his place as a noteworthy artist of his generation.

Conclusion

James Archer's artistic journey from Edinburgh to London reflects a career built on solid academic training, a keen understanding of Victorian tastes, and a versatile talent for narrative and portraiture. As a prominent member of the Royal Scottish Academy and a regular exhibitor in London, he contributed significantly to the artistic output of his era. His depictions of legendary heroes, literary figures, and idealized childhood captured the imagination of his contemporaries. While the Pre-Raphaelite movement undoubtedly influenced his style and choice of subject matter, Archer forged his own path, creating works that were both accomplished and accessible. His legacy endures in his paintings, which continue to offer valuable insights into the artistic and cultural currents of the 19th century, particularly within the Scottish tradition and the broader scope of British Victorian art.