Bartholomeus Spranger stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late 16th and early 17th-century European art. Born in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp on March 21, 1546, and passing away in Prague in August 1611, Spranger's life and career traversed the continent, absorbing and synthesizing diverse artistic currents. He rose to prominence as a leading exponent of Northern Mannerism, eventually becoming the esteemed court painter to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, a position that cemented his influence across Europe. His unique style, blending Italian sophistication with Northern sensibilities, left an indelible mark on the art of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Spranger's artistic journey began in Antwerp, one of the most vibrant cultural centers of Northern Europe during the 16th century. His initial training was under masters who specialized in different genres, providing him with a broad foundation. He apprenticed first with Jan Mandyn, a painter known for his imaginative, often grotesque scenes in the tradition of Hieronymus Bosch. Subsequently, he studied with Cornelis van Dalem, a painter recognized more for his landscape and architectural scenes, though fewer works survive to fully assess his style.

This early exposure to diverse Antwerp traditions likely instilled in Spranger a technical versatility and an openness to different modes of artistic expression. However, like many ambitious Northern artists of his generation, Spranger recognized the necessity of traveling south to Italy, the fountainhead of Renaissance and burgeoning Mannerist art, to truly refine his craft and elevate his status. After completing his apprenticeships around 1565, he embarked on the formative journey that would shape his mature style.

The Italian Sojourn: Rome and Beyond

Spranger's travels first took him to Paris, but the allure of Italy soon drew him southward. He arrived in Rome around 1566, immersing himself in the city's rich artistic environment. This period was crucial for his development. He diligently studied the works of Italian masters, absorbing the lessons of High Renaissance giants like Michelangelo and Raphael. The text also mentions exposure to Caravaggio, though chronologically, Caravaggio's major impact came slightly later; Spranger would certainly have been aware of the dramatic naturalism emerging in Rome during his later visits or through prints.

In Rome, Spranger found opportunities to practice his art, reportedly creating several murals and frescoes, honing his skills in large-scale composition. His talent did not go unnoticed. He worked in the circle associated with the Farnese family and collaborated with artists like Girolamo Mirola and Jacopo Zanguidi, known as Bertoia, particularly on decorations at the Villa Farnese in Caprarola. This interaction with contemporary Italian Mannerists was instrumental in shaping his elegant and complex figural style. His abilities earned him recognition, leading to significant patronage.

Court Appointments: From Papal Service to Imperial Prague

Spranger's rising reputation culminated in prestigious appointments. Around 1570, he entered the service of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, which facilitated further connections. The provided text mentions an appointment as court painter to Pope Pius V in 1575, although Pius V died in 1572; it's more likely he worked for the papal court under Pope Gregory XIII, possibly gaining initial favour during Pius V's reign or shortly after. His work for the papacy demonstrated his ability to handle significant commissions.

A major turning point came in 1575 when he was recommended to Emperor Maximilian II in Vienna by the sculptor Giambologna, another influential Flemish artist working in Italy. Spranger traveled to Vienna, beginning his long association with the Habsburg imperial court. Although Maximilian II died the following year, his successor, Emperor Rudolf II, recognized Spranger's exceptional talent.

In 1581, Spranger was summoned to Prague, which Rudolf II was transforming into a major European cultural capital. He was appointed court painter, eventually becoming the emperor's most favoured artist (Kammermaler). The text notes a date of 1608 for becoming Rudolf II's court painter, which might refer to his elevation to the principal position or a formal reconfirmation, as he was active in Prague much earlier. Prague under Rudolf II became a crucible for late Mannerism, attracting artists and intellectuals from across Europe, including figures like the painter Hans von Aachen and the Swiss artist Joseph Heintz the Elder, with whom Spranger worked closely.

Defining Northern Mannerism: Spranger's Artistic Style

Bartholomeus Spranger is best known as a leading master of Northern Mannerism, a style characterized by its artificiality, elegance, and intellectual sophistication. His work masterfully fused the elongated forms, complex poses (figura serpentinata), and erotic undertones of Italian Mannerism (influenced by artists like Parmigianino and Giulio Romano, whose work he would have known) with a Northern European precision in detail and a distinct sensibility.

His compositions are often intricate, featuring multiple figures intertwined in dynamic, sometimes ambiguous, spatial arrangements. He excelled in depicting the human form, particularly the nude, rendering figures with elongated limbs, graceful contours, and a polished, almost porcelain-like finish. These figures often convey intense emotions or are caught in moments of dramatic tension, typical of the Mannerist desire to move beyond the harmony and balance of the High Renaissance.

Spranger frequently explored mythological and allegorical themes, subjects highly favoured by the intellectual climate of Rudolf II's court. These themes allowed him to showcase his erudition and indulge in sensual depictions of gods, goddesses, and personifications. His colour palettes are often rich and vibrant, employing sophisticated harmonies and sometimes jarring contrasts to heighten the emotional impact. His line is fluid and expressive, defining forms with clarity and elegance. This distinctive blend of Italian grace and Northern specificity created a style that was both internationally appealing and uniquely his own, sometimes referred to as "Rudolfine Mannerism" due to its association with the Prague court.

Masterpieces and Thematic Concerns

Spranger's oeuvre includes numerous paintings that exemplify his style and thematic preoccupations. Among his most celebrated works is Venus and Adonis. This painting, existing in several versions, captures the emotional intensity of the myth, with Venus desperately trying to prevent her mortal lover Adonis from departing for the hunt that will lead to his death. The work is noted for its sensual depiction of the figures, intricate composition, and dynamic interplay of limbs and gazes, embodying the erotic charge often present in Spranger's mythological scenes.

Another key work, created for Emperor Rudolf II, is the Triumph of Wisdom (or Wisdom Conquers Ignorance). This allegorical painting depicts Minerva (Wisdom) triumphing over Ignorance and base desires. It is a complex allegory reflecting the Neoplatonic and humanist interests of the imperial court, executed with Spranger's characteristic elegance and sophisticated composition. The work served not only as decoration but also as a statement of the Emperor's intellectual and cultural aspirations.

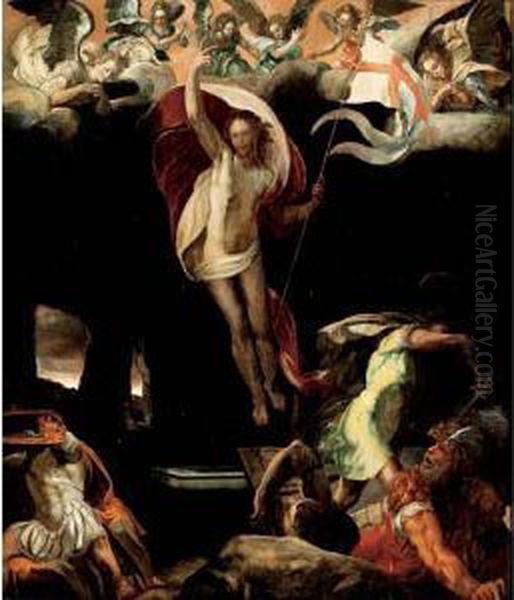

His repertoire also included religious subjects, often imbued with the same Mannerist sensibility. The Agony in the Garden, mentioned as an early work, likely showcased his ability to convey strong emotion through vivid colour and dynamic figures, even within a traditional Christian theme. Other notable works listed include Ulysses and Circe (referred to as Ulysses and Sylvia in the source text, likely a misnomer for the sorceress Circe), demonstrating his engagement with classical mythology.

Hercules and Omphale (likely intended by the source text's Hercules and Ophelia) depicts the mythological hero subjugated by the Lydian queen, a theme exploring the power dynamics between sexes, rendered with characteristic Mannerist flair. The Allegory of the Virgin Saint Ursula, described as a late work, highlights female strength and virtue, possibly reflecting the complex allegorical programs favoured at court. Mercury Carrying Psyche to Mount Olympus (likely intended by the source text's Mercury carrying Pan) showcases his skill in depicting airborne figures and complex, dynamic movement, a testament to his technical mastery developed during his Vienna and Prague years.

A Master Across Media: Painting, Prints, and Sculpture

While primarily known as a painter, Spranger's talents extended to other media. The sources confirm he was also active as a sculptor, though fewer works in this medium survive or are securely attributed. Perhaps more significantly for his widespread influence, he was a skilled draftsman and etcher, and his designs were frequently translated into engravings by other artists.

His relationship with the renowned Dutch printmaker Hendrick Goltzius was particularly fruitful. Goltzius engraved numerous compositions based on Spranger's designs, popularizing his intricate style across Northern Europe. These prints, known for their technical brilliance and faithful rendering of Spranger's elegant figures and complex compositions, were highly sought after and played a crucial role in disseminating the Mannerist aesthetic. Spranger's involvement was sometimes direct, as he is known to have occasionally corrected proofs sent by his engravers, indicating a close collaborative relationship.

This engagement with printmaking ensured that Spranger's artistic innovations reached a far wider audience than his paintings, many of which remained within imperial or aristocratic collections. Artists in the Netherlands, Germany, and France were exposed to his style through these prints, influencing figures like Karel van Mander, who praised Spranger highly in his Schilder-boeck (Book of Painters) of 1604. This wide dissemination cemented Spranger's reputation as a leading international master.

Context and Connections: Spranger Among Contemporaries

Spranger operated within a rich network of artists, patrons, and intellectuals. His time in Italy brought him into contact with the legacy of the High Renaissance and the innovations of contemporary Mannerists. His move to the Habsburg courts placed him at the center of imperial patronage, first in Vienna and then, most importantly, in Prague under Rudolf II.

In Prague, he was a central figure in the "Rudolfine" school of artists, working alongside Hans von Aachen, Joseph Heintz the Elder, the sculptor Adriaen de Vries, and others. This cosmopolitan group fostered a unique artistic environment characterized by technical refinement, intellectual depth, and a penchant for the exotic and erotic.

While the provided text notes no direct evidence of collaboration or explicit competition with slightly later Flemish giants like Peter Paul Rubens or members of the Bruegel dynasty, Spranger's work represents a distinct phase in Netherlandish art. His highly stylized, elegant Mannerism contrasts with the burgeoning Baroque dynamism that Rubens would later champion upon his return from Italy. Spranger's influence, however, can be seen in the early works of some artists who transitioned towards the Baroque. His emphasis on dynamic composition and expressive figures laid groundwork that later artists built upon, even as they moved in different stylistic directions. His primary interactions seem to have been collaborative, particularly with the engravers who spread his designs.

Mysteries, Anecdotes, and Unresolved Questions

Despite his prominence, aspects of Spranger's life and work remain shrouded in some mystery, contributing to his allure. One anecdote involves a painting, possibly the Witches' Sabbath, originally acquired by one Giovanni Clovio but later passing to the famous miniaturist Giulio Clovio, becoming a significant piece in the latter's collection. Such stories hint at the complex paths artworks could take through patronage and collecting circles.

The source material also mentions speculation about potential links between Spranger and Reformation ideas, though this remains unproven and requires careful consideration against his long service to Catholic patrons like the Pope and the Habsburg Emperors. His complex allegorical works, like the Triumph of Wisdom, undoubtedly contain layers of meaning, possibly including political or personal commentary that is not always fully decipherable today, adding to their enigmatic quality.

Art historians also note certain stylistic quirks, such as the repetition of specific female facial types across different works, or his distinctive handling of light and shadow. Furthermore, questions persist regarding the attribution and dating of some works sometimes associated with him. An intriguing but vague story mentions a portrait painted for a banker's daughter, later sold to Clovio, highlighting the gaps in our knowledge about his commissions and the fate of individual pieces. Many of his most important works remained relatively inaccessible within the imperial collections for centuries, contributing to his later period of obscurity.

Legacy, Rediscovery, and Art Historical Standing

During his lifetime, Bartholomeus Spranger enjoyed considerable fame and prestige, particularly through his association with the imperial court and the widespread circulation of prints after his designs. He was considered a leading master of his generation, admired for his technical skill, imaginative compositions, and sophisticated style. Karel van Mander lauded him as a model for aspiring artists.

However, following his death and the dispersal of Rudolf II's collections after the Thirty Years' War, Spranger's reputation gradually faded. The rise of the Baroque style, championed by artists like Rubens and Rembrandt, shifted artistic tastes away from the perceived artificiality of Mannerism. For several centuries, Spranger was relatively neglected by art history, overshadowed by artists of the High Renaissance before him and the Baroque masters who followed.

It was not until the late 20th century that scholars began to re-evaluate Mannerism and rediscover the brilliance of artists like Spranger. Exhibitions and scholarly publications shed new light on his achievements and the cultural richness of Rudolfine Prague. Today, Spranger is recognized as a crucial figure in late 16th-century European art. He is lauded for his role in developing and disseminating Northern Mannerism, his technical virtuosity across multiple media, and his ability to synthesize Italian and Northern European artistic traditions.

He is now understood as a truly "international" artist, whose career path and stylistic fusion exemplify the cross-cultural exchanges that characterized the period. His work is appreciated for its elegance, complexity, and psychological depth, offering insights into the sophisticated, often esoteric, world of the late Renaissance courts. His influence on contemporaries, particularly through prints by Goltzius and others, is acknowledged as significant for the development of art in the Netherlands and beyond.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Bartholomeus Spranger remains a compelling figure in art history. From his beginnings in Antwerp to his formative years in Italy and his celebrated career at the imperial court in Prague, he forged a unique and influential artistic identity. As a master of Northern Mannerism, he created works of captivating elegance, intellectual depth, and sensual allure. His technical proficiency extended beyond painting to sculpture and, crucially, to designs for prints that broadcast his style across Europe. Though once obscured by changing tastes, his rediscovery has rightfully restored him to a prominent place as a key innovator and a vital link in the chain of European art, whose sophisticated vision continues to fascinate scholars and art lovers alike.