Nicolas Sinezouboff, a name that resonates with the quiet dedication of an artist navigating the tumultuous currents of early to mid-20th century European art, offers a fascinating study of a painter who bridged Russian artistic sensibilities with the vibrant atmosphere of Paris. Born in Russia in 1891, his life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and societal upheaval, culminating in his death in 1956. Primarily a painter, Sinezouboff wielded his brush to capture the world around him, predominantly through the medium of oil, creating evocative landscapes and intimate still lifes that continue to find appreciation in art circles.

Early Influences and the Russian Context

While specific details of Nicolas Sinezouboff's earliest artistic training remain somewhat elusive in readily available records, his emergence as an artist in Russia during the early 20th century places him within a rich and complex artistic environment. The preceding decades had seen the dominance of the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers), such as Ilya Repin and Ivan Shishkin, who championed realism and a national Russian character in art. Concurrently, the turn of the century brought the influence of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, embodied by the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement, with figures like Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst looking towards both Russian traditions and Western European aesthetics.

It was against this backdrop, and the seismic shifts of the Russian Revolution, that Sinezouboff would have formed his initial artistic identity. The revolutionary period itself unleashed a torrent of avant-garde movements, from the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich to the Constructivism of Vladimir Tatlin. However, not all artists were drawn to radical abstraction. Many sought to find new paths that still honored figurative traditions or explored spiritual dimensions in art, which leads us to Sinezouboff's significant early affiliation.

The Makovets Society: A Spiritual Quest in Art

A pivotal aspect of Sinezouboff's early career was his involvement with the Makovets art society. He became a member of this Moscow-based group in 1921, a collective of artists and poets who sought a path distinct from both the increasingly institutionalized avant-garde and purely academic art. The name "Makovets" itself refers to the hill on which the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius stands, a spiritual center of Russia, signaling the group's inclination towards art imbued with spiritual and philosophical depth.

The Makovets artists, including prominent figures like Vasily Chekrygin (sometimes spelled Chekhrykin), a visionary artist and theorist, and Sergei Gerasimov, aimed to create an art that was both modern and deeply rooted in human experience and cultural heritage. They drew inspiration from early Italian Renaissance art, Russian icon painting, and German Romanticism. The influential philosopher and theologian Pavel Florensky was also closely associated with the group, providing intellectual and spiritual underpinnings to their endeavors. Other notable members included Artur Fonvizin and Lev Zhegin.

Sinezouboff's participation in Makovets indicates his alignment with these ideals. In 1922, he participated in the "Erste Russische Kunstausstellung" (First Russian Art Exhibition) in Berlin, held at the Galerie van Diemen. This landmark exhibition showcased a wide spectrum of Russian art, from the avant-garde to more traditional forms, and Sinezouboff's inclusion, likely as part of the Makovets contingent, would have exposed his work to an international audience. While the precise nature of his role within Makovets isn't extensively documented, his membership and exhibition activity confirm his active participation in this significant post-revolutionary artistic current.

The Parisian Chapter: Montmartre and the École de Paris

At some point, likely in the 1920s or early 1930s, Sinezouboff, like many Russian artists and intellectuals of his generation, emigrated from the Soviet Union. Paris, long a beacon for artists worldwide, became his new home and a significant source of inspiration. This move placed him within the vibrant, cosmopolitan milieu often referred to as the École de Paris (School of Paris). This was not a formal institution but rather a term describing the diverse community of foreign-born artists who flocked to the French capital, particularly to neighborhoods like Montparnasse and Montmartre, between the wars and beyond.

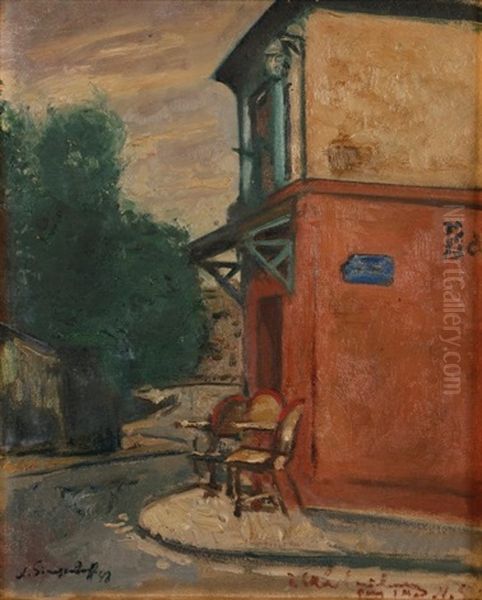

Sinezouboff's presence in Paris is evidenced by works such as Café in Montmartre (also known as Montmartre, le Café Rose), dated 1948. Montmartre, with its historic charm, bustling street life, and artistic legacy stretching back to the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, provided rich subject matter. His depiction of a café scene suggests an immersion in the daily life and atmosphere of his adopted city. He would have been working alongside or in the vicinity of a multitude of artists, from established figures to emerging talents. The École de Paris included fellow Russians like Marc Chagall and Chaim Soutine (Lithuanian-French, but central to this group), as well as artists from across Europe like Amedeo Modigliani and Moïse Kisling.

His painting Bouquet de fleurs dans une vase (Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase) from 1942 further situates him within the Parisian art scene during a challenging period, the German occupation. Despite the difficulties, artistic life, albeit subdued, continued.

Artistic Style: Realism and Impressionistic Sensibilities

Nicolas Sinezouboff's artistic style is generally characterized as a blend of Realism and Impressionism. His commitment to representational art is evident in his landscapes, cityscapes, and still lifes. The term "Realism" in his context likely refers to a faithful depiction of his subjects, capturing their tangible qualities and everyday essence, rather than the more politically charged Social Realism that would later become dominant in the Soviet Union.

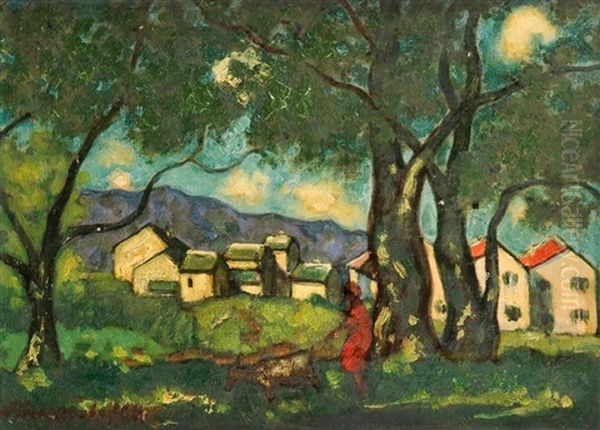

His Impressionistic leanings are apparent in his handling of light and color, particularly in his landscapes. Works like Morning on the Edge of the Village (1938) and Le matin au bois de Vincennes (Morning in the Bois de Vincennes) suggest an artist keen on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, a hallmark of Impressionism. This approach would have found resonance in Paris, the birthplace of Impressionism, where the legacy of artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro continued to inform landscape painting. Sinezouboff's street scenes and park views likely employed broken brushwork and a brightened palette to convey the vibrancy of the Parisian environment.

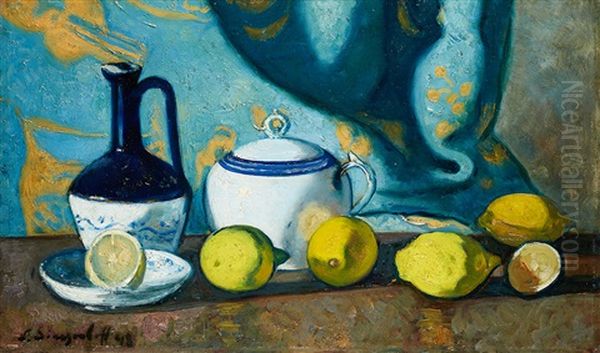

His still lifes, such as Nature morte aux citrons (Still Life with Lemons), allowed for a more controlled exploration of form, texture, and color harmony. This genre, with its rich tradition in European art, provided a space for quiet contemplation and technical skill.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Sinezouboff's oeuvre, as gleaned from auction records and art historical mentions, reveals a consistent engagement with several key themes:

Urban Landscapes and City Life: His Parisian scenes, particularly those of Montmartre like Café in Montmartre (1948), capture the unique ambiance of the city. These works often focus on public spaces, moments of leisure, and the architectural character of Paris. He shares this thematic interest with artists like Maurice Utrillo, who was famed for his depictions of Montmartre.

Rural Landscapes and Nature: Paintings such as Morning on the Edge of the Village (1938) and Bergère aux abords du village (Shepherdess on the Outskirts of the Village) showcase his interest in the countryside. These works often evoke a sense of tranquility and a connection to the natural world, rendered with an eye for atmospheric conditions. Le matin au bois de Vincennes also falls into this category, depicting one of Paris's large public parks, a space where city and nature meet.

Still Lifes: Compositions like Nature morte aux citrons and Bouquet de fleurs dans une vase (1942) demonstrate his skill in this traditional genre. Still lifes offered Sinezouboff an opportunity to focus on the interplay of light, color, and texture in a controlled setting, often imbuing everyday objects with a quiet dignity.

While his style might not have been at the cutting edge of avant-garde experimentation prevalent during much of his career (with figures like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque revolutionizing form), Sinezouboff's work represents a persistent strand of figurative painting that valued keen observation, skilled execution, and an appreciation for the visual poetry of the everyday.

Later Career and Legacy

Nicolas Sinezouboff continued to paint through the 1940s and into the 1950s, until his death in 1956. His later works, predominantly created in France, reflect a mature artist confident in his stylistic approach, which synthesized his Russian artistic heritage with the influences of his adopted Parisian environment. He remained committed to a form of expressive realism, often imbued with the light and atmospheric qualities of Impressionism.

His works appear periodically in auctions, indicating a sustained, if perhaps niche, interest among collectors. He may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his more radical contemporaries or fellow émigrés, but Sinezouboff's contribution lies in his consistent artistic vision and his role as a conduit between different cultural and artistic traditions. He represents a generation of artists who, displaced by political and social turmoil, found new creative homes and contributed to the rich tapestry of 20th-century European art.

His connection to the Makovets society links him to an important, though sometimes overlooked, chapter in early Soviet art that sought spiritual depth and a connection to tradition. His subsequent career in Paris places him within the diverse and international École de Paris, a testament to the city's enduring magnetism for artists.

In conclusion, Nicolas Sinezouboff was an artist whose journey took him from the fervent artistic debates of post-revolutionary Russia to the established art world of Paris. His paintings, characterized by their realistic depiction, impressionistic handling of light, and focus on landscapes, cityscapes, and still lifes, offer a window into the world as he saw it. He was a dedicated painter who, while perhaps not a revolutionary innovator in the mold of some of his contemporaries like Joan Miró or Max Ernst who were also active in Paris, nonetheless carved out a distinct artistic path, leaving behind a body of work that speaks to a sensitive eye and a skilled hand. His art serves as a reminder of the many individual talents who contributed to the complex and multifaceted story of 20th-century art.