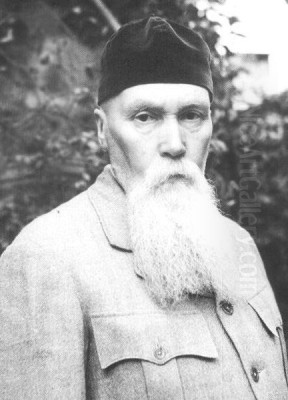

Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich stands as a unique and towering figure in the cultural landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in St. Petersburg, Russian Empire, on October 9, 1874, and passing away in Naggar, Kullu Valley, India, on December 13, 1947, Roerich's life encompassed an astonishing range of activities. He was a prolific and highly original painter, a dedicated archaeologist, an intrepid explorer, a writer, a philosopher, a spiritual teacher, and a tireless advocate for peace and the preservation of cultural heritage. His journey took him from the heart of Imperial Russia through the upheavals of revolution, across continents, and deep into the mystical landscapes of the Himalayas, leaving behind a legacy as complex and vibrant as his canvases.

Roerich's multifaceted career defies easy categorization. His art, instantly recognizable for its luminous colours and spiritual depth, drew inspiration from ancient Russian history, folklore, Eastern philosophies, and the majestic mountain ranges he explored. Simultaneously, his intellectual pursuits led him to co-create a spiritual philosophy known as Agni Yoga, and his humanitarian concerns culminated in the Roerich Pact, an international treaty dedicated to protecting cultural treasures during times of conflict. Understanding Roerich requires exploring these interwoven threads of art, spirituality, exploration, and activism that defined his extraordinary life.

Early Life and Formative Influences in St. Petersburg

Nikolai Roerich was born into a prosperous and cultured family in St. Petersburg. His father, Konstantin Fyodorovich Roerich, was a respected lawyer and notary of Baltic German and Russian descent, while his mother, Maria Vasilyevna Kalashnikova, came from a Russian merchant family. This comfortable background provided young Nikolai with access to education and the vibrant intellectual and artistic life of the Russian capital during its famed Silver Age.

From an early age, Roerich displayed a keen interest in history, archaeology, and drawing. His family's country estate, Izvara, southwest of St. Petersburg, offered ample opportunity to explore nature and ancient burial mounds (kurgans), sparking a lifelong fascination with the past. These early archaeological explorations, often conducted during his boyhood, were not mere hobbies; they laid the foundation for his later scholarly work and deeply influenced the subject matter of his art.

His formal education reflected his diverse interests. Roerich simultaneously enrolled at the Imperial Academy of Arts, studying under the renowned landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi, and at St. Petersburg University, where he studied law, following his father's wishes, alongside history and philology. This dual path provided him with both the technical skills of an artist and the intellectual rigor of a scholar, a combination that would characterize his entire career.

The Emergence of an Artist: Symbolism and the Russian Soul

At the Academy of Arts, Roerich absorbed the prevailing artistic currents, particularly the influence of Russian Symbolism. Unlike French Symbolism's focus on decadence and introspection, Russian Symbolism often looked towards national history, folklore, and spiritual traditions for inspiration. Artists like Mikhail Vrubel were exploring mystical themes and innovative forms, creating a fertile ground for Roerich's own developing vision. His teacher, Kuindzhi, known for his dramatic, light-filled landscapes, undoubtedly influenced Roerich's later mastery of colour and atmosphere.

Roerich quickly gained recognition within St. Petersburg's artistic circles. He became associated with the influential critic Vladimir Stassov, a champion of Russian national art. Stassov introduced Roerich to prominent figures like the composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and the painter Ilya Repin, further integrating him into the cultural elite. His graduation piece from the Academy, The Messenger: Tribe Has Risen Against Tribe (1897), depicting a scene from ancient Slavic history, was purchased by the famous collector Pavel Tretyakov, signalling Roerich's arrival as a significant artistic talent.

This early work established themes that would recur throughout his career: a deep connection to Russia's ancient past, a sense of epic history, and a distinctive style characterized by bold compositions, clear lines, and resonant colour. Works like Guests from Overseas (1901) further explored these historical narratives, depicting Viking ships arriving in Slavic lands, rendered with a decorative clarity and vibrant palette that hinted at his future stylistic direction.

Mir Iskusstva: The World of Art Movement

Roerich became a key figure in the influential Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement, founded by artists like Alexandre Benois and Sergei Diaghilev. This group sought to revitalize Russian art by embracing both national traditions and contemporary European styles, particularly Art Nouveau and Symbolism. They reacted against the perceived academicism of the later Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, advocating for aestheticism, artistic synthesis (Gesamtkunstwerk), and high standards of craftsmanship in painting, graphic arts, and stage design.

Roerich joined the society and exhibited with them regularly. He served as a member from 1902 to 1910 and later became the chairman of the renewed Mir Iskusstva society from 1910 to 1913. His involvement placed him at the centre of Russia's avant-garde, alongside figures like Léon Bakst, Konstantin Somov, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and others who were shaping the visual culture of the era. The group's journal and exhibitions promoted a sophisticated, often stylized aesthetic that resonated with Roerich's own inclinations.

His association with Diaghilev proved particularly fruitful. Diaghilev, the impresario who would soon stun Europe with his Ballets Russes, recognized Roerich's unique talent for evoking historical atmosphere and dramatic mood. This connection led to significant commissions in stage design, a field where Roerich would make some of his most lasting contributions.

Designs for the Stage: The Ballets Russes

Roerich's work for the theatre, particularly for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, brought his art to international attention. His deep knowledge of history and archaeology, combined with his powerful sense of colour and design, made him an ideal collaborator for productions aiming for historical authenticity and striking visual impact.

His most famous theatrical work was undoubtedly the set and costume design for Igor Stravinsky's revolutionary ballet, Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), which premiered tumultuously in Paris in 1913. Roerich, who also co-authored the libretto with Stravinsky, drew upon his extensive research into ancient Slavic rituals and pagan culture. His designs featured primitive, earth-toned costumes and stark, evocative backdrops depicting sacred groves and sacrificial sites, perfectly complementing the ballet's dissonant score and primal choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky. The designs were integral to the work's shocking power and remain iconic examples of modernist stagecraft.

Beyond The Rite of Spring, Roerich designed several other productions for Diaghilev, including Alexander Borodin's Polovtsian Dances from the opera Prince Igor. His vibrant, dynamic sets and costumes for this production, first seen in Paris in 1909, were a sensational success, contributing significantly to the early triumphs of the Ballets Russes and establishing a Western fascination with exotic Russian themes. His theatrical work demonstrated his ability to synthesize historical research, artistic vision, and dramatic necessity.

Artistic Style: Colour, Mountains, and Mysticism

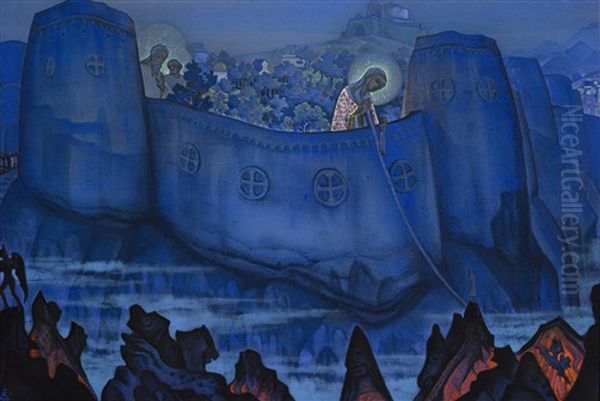

Roerich's mature artistic style is highly distinctive and instantly recognizable. He developed a unique approach using tempera paints, which allowed for exceptionally vibrant, luminous, and non-reflective surfaces. His colours are often bold, pure, and arranged in broad, flat planes, reminiscent of icon painting or mosaics, yet imbued with a modern sensibility. He favoured blues, purples, pinks, and oranges, often using them to depict skies and mountains at dawn or dusk, creating an atmosphere of otherworldly beauty and profound stillness.

His subject matter evolved but remained rooted in history, spirituality, and landscape. Early works focused on ancient Russia, its folklore, saints, and heroes (Alexander Nevsky, The Battle in the Heavens). Later, following his extensive travels, the Himalayas became his dominant motif. He painted hundreds of canvases depicting the towering peaks of Kanchenjunga, Everest, and the ranges of Tibet and Ladakh. These are not merely topographical records; they are spiritual landscapes, imbued with a sense of majesty, mystery, and the divine presence Roerich felt in these remote regions. Titles like Path to Shambhala or Burning of Darkness reflect the mystical quest that underpinned his explorations.

While associated with Symbolism, Roerich's art transcends easy labels. It incorporates elements of Art Nouveau's decorative qualities, Post-Impressionism's emphasis on colour and form, and a unique spiritual intensity derived from his philosophical interests. His figures are often stylized, appearing as archetypes within epic landscapes, conveying universal themes of struggle, enlightenment, and the connection between humanity and the cosmos. His work stands apart from many contemporaries like Wassily Kandinsky, who moved towards pure abstraction; Roerich always retained a connection to the representational, albeit infused with symbolic meaning.

Archaeology and the Search for Origins

Roerich's passion for archaeology was not separate from his art but deeply intertwined with it. Throughout his life, he conducted archaeological surveys and excavations, first in the regions around St. Petersburg and Novgorod, later in Central Asia and the Himalayas. He was particularly interested in the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the migration patterns of ancient peoples, seeking connections between cultures across Eurasia.

His findings informed the historical accuracy and atmosphere of his paintings depicting ancient Slavic life. He published scholarly articles on his archaeological research and amassed a significant collection of prehistoric artifacts. This deep immersion in the material remains of the past gave his historical paintings a unique sense of authenticity and gravitas.

His later expeditions, particularly the Central Asian Expedition, had significant archaeological components. He sought evidence of ancient trade routes, cultural exchange, and the possible common origins of Slavic, Indian, and Tibetan cultures. For Roerich, archaeology was a way to uncover the shared roots of humanity and to understand the deep historical currents that shaped civilizations, a theme central to both his art and his philosophical outlook.

Revolution, Emigration, and the American Period

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 marked a decisive turning point in Roerich's life. While initially involved in committees for the preservation of art treasures under the Provisional Government, the increasing chaos and hostility towards the intelligentsia led him and his family to leave Russia. They initially resided in Finland and Scandinavia, where Roerich continued to paint and exhibit. He then spent time in London before accepting an invitation to travel to the United States in 1920 for an exhibition tour organized by the Art Institute of Chicago.

The American tour was a major success, introducing Roerich's art to a wide audience and establishing his international reputation. He decided to remain in the US, settling in New York City. The American period was incredibly productive. He painted prolifically, lectured widely, and, with the support of a dedicated group of admirers and patrons, established several cultural institutions.

These included the Master Institute of United Arts (an art school promoting synthesis of the arts), Corona Mundi (an international art center), and the first Roerich Museum, which housed his growing collection of paintings. He attracted a circle of influential followers, including the future Secretary of Agriculture (and later Vice President) Henry A. Wallace. During this time, he also interacted with various cultural figures, including, reportedly, the writer H.P. Lovecraft, who mentioned Roerich's New York residence in his correspondence.

The Great Central Asian Expedition (1923-1928)

Fueled by his lifelong interest in Eastern cultures and a quest for spiritual wisdom, Roerich embarked on an ambitious and arduous expedition across Central Asia. Accompanied by his wife Elena and son Yuri (a budding Tibetologist), the expedition traversed vast and often dangerous territories, including Sikkim, Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Pass, Khotan (Xinjiang), the Altai Mountains, Mongolia, and Tibet.

The stated goals were artistic and scientific: to paint the landscapes, study the flora and fauna, conduct archaeological research, and investigate the languages and customs of the regions. Roerich produced hundreds of paintings during this journey, capturing the stunning beauty and spiritual aura of the Himalayas and the high plateaus. Yuri conducted linguistic and ethnographic research.

However, the expedition was also shrouded in mystery and political intrigue. Roerich carried credentials that suggested diplomatic or intelligence connections, possibly with both Soviet and Western powers. There were persistent rumors that he was searching for Shambhala, the legendary hidden kingdom believed by some Tibetan Buddhists to be a source of profound spiritual wisdom and a harbinger of a new era. The expedition faced extreme hardships, including treacherous terrain, harsh weather, political obstacles, and a harrowing five-month detention by Tibetan authorities during the winter of 1927-28. Despite the difficulties, the expedition cemented Roerich's image as a fearless explorer and mystic.

Agni Yoga: The Path of Living Ethics

Parallel to his artistic and exploratory activities, Roerich, together with his wife Elena Ivanovna Roerich, developed a spiritual and philosophical teaching known as Agni Yoga or Living Ethics. Elena played a crucial role, claiming to receive telepathic communications from spiritual masters (Mahatmas), particularly Master Morya, a figure also prominent in Theosophy, the movement founded by Helena Blavatsky. These communications formed the basis of the Agni Yoga books.

Agni Yoga presents itself not as a religion but as a practical ethical system for daily life, emphasizing self-improvement, service to humanity, the reality of a spiritual hierarchy, and the importance of beauty and culture for spiritual evolution. It seeks to synthesize ancient Eastern wisdom (particularly Buddhist and Hindu concepts like karma and reincarnation) with modern scientific understanding and Western philosophical traditions. The "Agni" (Sanskrit for fire) symbolizes the cosmic energy of the heart and consciousness that practitioners aim to cultivate.

Roerich's art became deeply infused with the principles of Agni Yoga. His paintings often depict spiritual seekers, sages, and symbolic representations of cosmic forces, set against the backdrop of the majestic Himalayas, seen as a spiritual center of the planet. The Agni Yoga Society, founded by his followers in New York in 1921, continues to disseminate the teachings worldwide.

The Roerich Pact and Pax Cultura

Deeply concerned by the destruction of cultural heritage he witnessed during World War I and the Russian Revolution, Roerich dedicated significant effort to promoting international protection for artistic and scientific institutions and historical monuments. He conceived of an international agreement, analogous to the Red Cross for humanitarian protection, specifically for culture.

He proposed a symbol for this protection: the Banner of Peace. It consists of three solid circles within a larger circle, rendered in magenta on a white background. Roerich described the symbol as representing Religion, Art, and Science embraced by the circle of Culture, or alternatively, Past, Present, and Future within the circle of Eternity. This ancient symbol can be found across various cultures and epochs.

His tireless advocacy led to the drafting of the Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments, commonly known as the Roerich Pact. After several international conferences, the Pact was signed at the White House in Washington D.C. on April 15, 1935, by representatives of the United States and 21 other nations of the Pan-American Union. The Pact obliges signatory nations to respect the neutrality of and protect cultural sites in times of both peace and war. Though its enforcement mechanisms were limited, the Roerich Pact was a landmark achievement, establishing the principle that cultural heritage is the patrimony of all humanity and laying important groundwork for later UNESCO conventions, such as the 1954 Hague Convention. Roerich was nominated multiple times for the Nobel Peace Prize for this initiative.

The Manchurian Expedition and Political Controversy

Following the success of the Roerich Pact, Roerich embarked on another expedition in 1934-1935, this time to Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. This expedition was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Secretary Henry A. Wallace, ostensibly to collect drought-resistant grasses that could help combat the Dust Bowl conditions devastating the American Great Plains.

However, this expedition became mired in controversy and accusations of political maneuvering. Critics alleged that Roerich, possibly influenced by his spiritual beliefs about a coming era of geopolitical transformation centered in Asia, was using the expedition as cover for his own political ambitions or intelligence gathering, perhaps aiming to create a new pan-Buddhist state in the region. His actions, including raising the Banner of Peace alongside national flags and engaging in complex local politics, alarmed both Chinese and Japanese authorities, as well as his American sponsors.

The situation escalated into a public scandal. Wallace, feeling misled and politically exposed, publicly repudiated Roerich and withdrew support. The U.S. government launched a tax investigation into Roerich's finances and institutions. This controversy severely damaged Roerich's reputation in the United States and effectively ended his close relationship with the American establishment. He never returned to the US after this expedition.

Final Years in India: The Kullu Valley

After the Manchurian debacle, Nikolai Roerich and his family settled permanently in Naggar, a village in the picturesque Kullu Valley in the Indian Himalayas (present-day Himachal Pradesh). They had established a home and research base there in 1928, following the Central Asian Expedition. Here, Roerich spent the last decade of his life, surrounded by the mountains that had become his greatest source of inspiration.

In Naggar, he founded the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, dedicated to ethnographic, linguistic, botanical, and archaeological studies of the region. His son Yuri directed much of the scientific work, while Roerich continued to paint with undiminished energy, producing many of his most celebrated Himalayan landscapes. His home became a center for cultural exchange, visited by scholars, artists, and dignitaries, including Indian leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi, and the poet Rabindranath Tagore.

During World War II, Roerich actively supported the Allied cause and the Soviet Union's struggle against Nazism through his writings and art, painting heroic scenes from Russian history. He expressed a desire to return to his homeland after the war but was denied permission by the Soviet authorities. He passed away peacefully in Naggar on December 13, 1947, at the age of 73. His body was cremated according to local custom on a mountainside overlooking the valley he loved.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Nikolai Roerich left behind an immense and diverse legacy. His artistic output comprises over 7,000 paintings, now housed in museums and private collections worldwide, including major dedicated Roerich Museums in Moscow, St. Petersburg, New York, and Naggar. His distinctive style, characterized by spiritual intensity and vibrant colour, continues to captivate audiences. His Himalayan paintings, in particular, are revered for their sublime beauty and mystical atmosphere.

His contributions extend far beyond painting. The Roerich Pact remains a significant milestone in the history of international cultural heritage law. The Agni Yoga philosophy continues to attract followers globally, offering a path of ethical living and spiritual development. The Urusvati Institute, though its activities diminished after his death, stands as a testament to his vision of integrating scientific and spiritual inquiry.

However, his legacy is not without complexity. His deep involvement in mysticism and esoteric philosophy attracts fervent admiration from some but skepticism or dismissal from others. The political controversies surrounding his expeditions, particularly the Manchurian venture, cast a shadow over his reputation, raising questions about the interplay between his spiritual ideals and worldly ambitions. His relationship with both the Soviet Union and the United States remained ambiguous and often fraught.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Worlds

Nikolai Roerich was a true Renaissance man of the modern era, a figure whose life and work bridged multiple worlds: East and West, art and science, spirituality and activism, ancient history and contemporary concerns. He was driven by a profound belief in the unifying power of beauty and culture, and a deep spiritual quest for wisdom and enlightenment. His paintings transport viewers to realms of epic history and transcendent mountain vistas, while his philosophical writings challenge them to pursue a path of "Living Ethics."

His tireless efforts to protect cultural heritage through the Roerich Pact demonstrated a practical commitment to preserving the highest achievements of humanity for future generations. While controversies and unanswered questions remain about certain aspects of his life, particularly his political engagements, his overall contribution as an artist, thinker, and cultural visionary is undeniable. Nikolai Roerich remains an inspiring, if enigmatic, figure whose multifaceted legacy continues to resonate across cultures and disciplines, urging a synthesis of the material and the spiritual in the pursuit of a more harmonious world.