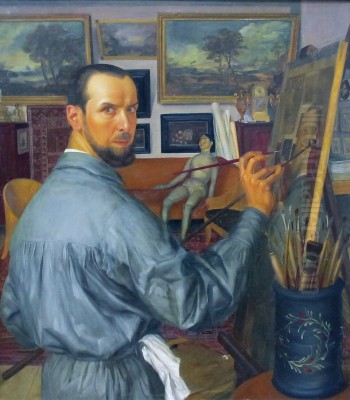

Alexandre Evgenievich Iacovleff, also known as Alexander Evgenievich Yakovlev (June 25, 1887 – May 12, 1938), stands as a significant figure in early 20th-century Russian and international art. A master draftsman, painter, and designer associated with the Neoclassical movement, Iacovleff forged a unique path, combining rigorous academic training with an insatiable curiosity about the world. His extensive travels across Europe, Asia, and Africa provided the subjects for his most celebrated works, creating a powerful visual record of diverse cultures through a distinctively precise and elegant lens. His life and art bridge the traditions of Russian art, the innovations of the Parisian scene, and the spirit of exploration that characterized the interwar period.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in St. Petersburg

Born in St. Petersburg into the family of a naval officer and inventor, Iacovleff displayed artistic talent from a young age. This inclination led him to the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, where he studied from 1905 to 1913. His time at the Academy was formative, particularly his studies under the influential painter and educator Dmitry Kardovsky. Kardovsky instilled in his students a strong foundation in drawing and classical principles, which would remain central to Iacovleff's practice throughout his career.

During his studies, Iacovleff formed a close and lifelong friendship with fellow student Vasily Shukhaev. Their artistic sensibilities were remarkably aligned, focusing on Neoclassical ideals, technical precision, and a shared admiration for the masters of the Italian Renaissance. They became inseparable, often referred to as "the twins," and their collaborative spirit would manifest in shared travels and artistic pursuits. Early exposure to the works of Renaissance giants like Andrea Mantegna and Piero della Francesca deeply influenced Iacovleff, shaping his appreciation for clear composition, linear definition, and monumental form.

The Mir Iskusstva Connection and Early Travels

While developing his Neoclassical style, Iacovleff was associated with the vibrant Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement. This influential group, spearheaded by figures like Sergei Diaghilev and Alexandre Benois, sought to revitalize Russian art by synthesizing various art forms – visual arts, theatre, music, and dance – and looking towards both European artistic heritage and Russian folk traditions. Though perhaps not a core member in the same vein as Léon Bakst or Konstantin Somov, Iacovleff shared the movement's emphasis on high aesthetic standards and draftsmanship.

His connection to this circle likely facilitated his early exposure and integration into broader artistic currents. A pivotal moment came in 1913 when, having received a travelling scholarship, Iacovleff and Shukhaev embarked on a journey to Italy and Spain. This trip was crucial, allowing them to study Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces firsthand, further cementing their commitment to classical techniques and figurative representation. The experience abroad honed their skills and broadened their artistic horizons beyond the confines of the St. Petersburg academy.

Venturing East: Documenting China and Japan

Following his academic success and early travels, the tumultuous events of the Russian Revolution and its aftermath led Iacovleff to spend significant time abroad. From 1917 to 1919, he undertook a major journey to the Far East, traveling through Mongolia, China, and Japan. This period marked a significant development in his art, shifting his focus towards ethnographic documentation and the portrayal of non-European cultures, albeit through his established Neoclassical lens.

In China and Japan, Iacovleff was captivated by the local cultures, particularly the traditional theatre. He produced a remarkable series of drawings and paintings depicting actors, dancers, street scenes, and local inhabitants. Works from this period showcase his exceptional ability to capture likeness and character with precision and sensitivity. He employed techniques like sanguine, charcoal, and tempera, rendering intricate costumes and expressive faces with meticulous detail. This journey established a pattern that would define his career: using his artistic skills to record the human diversity he encountered on his travels.

Chronicler of the Croisière Noire: Across Africa

Iacovleff's reputation as a skilled draftsman and observer of cultures led to his participation in one of the great adventures of the era: the Citroën-Haardt Trans-African Expedition, known as the Croisière Noire (Black Cruise), from 1924 to 1925. Serving as the official artist, he journeyed across the African continent, from Algeria through the Sahara, French West Africa, the Congo, and eventually reaching Madagascar. This expedition, equipped with Citroën half-track vehicles, aimed to showcase French industrial prowess and explore vast territories.

For Iacovleff, it was an unparalleled opportunity to document the peoples and landscapes of Africa. He created hundreds of drawings and paintings, primarily portraits executed with astonishing speed and accuracy, often using sanguine and pastels. His works from the Croisière Noire are celebrated for their objective yet deeply human portrayal of individuals from diverse ethnic groups. Avoiding romanticized exoticism, he focused on capturing the dignity, character, and unique features of his subjects. This monumental body of work earned him widespread acclaim upon his return to Paris and resulted in the French government awarding him the Legion of Honour in 1926. His approach stood in contrast to the Primitivism of artists like Paul Gauguin, emphasizing detailed observation over stylistic abstraction.

The Epic Croisière Jaune: Journey Through Asia

Building on the success of the African expedition, Iacovleff was again appointed official artist for the even more ambitious Citroën-Haardt expedition, the Croisière Jaune (Yellow Cruise), which traversed Asia from 1931 to 1932. This epic journey began in Beirut and led through Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, the Himalayas, the Gobi Desert, and finally into China. The expedition faced immense challenges, including treacherous mountain passes, extreme weather, and political instability.

Throughout this arduous trek, Iacovleff continued his mission of artistic documentation. He captured the dramatic landscapes of the Pamir Mountains, the deserts of Central Asia, and the ancient cities along the route. His portraits from this period depict Afghan warriors, Tibetan monks, Chinese officials, and nomadic peoples, rendered with his characteristic precision and psychological insight. Works such as Campement sur la route du Cachemire (Camp on the Road to Kashmir) exemplify his ability to combine ethnographic detail with masterful composition and atmospheric effect. The Croisière Jaune further solidified his reputation as an artist-explorer, a visual chronicler of worlds then largely inaccessible to the West.

Mastery of Form: Style and Technique

Alexandre Iacovleff's artistic style is most accurately described as Neoclassical, characterized by a strong emphasis on drawing, linear clarity, anatomical precision, and balanced composition. He remained committed to figurative representation throughout his career, largely untouched by the abstract currents of modernism that swept through Paris during his time there. His work often incorporated elements of Orientalism, not in the romantic or fantastical vein of 19th-century painters like Eugène Delacroix, but as a direct, observational response to the cultures he encountered. Some critics have termed his style "Exotic Academicism," highlighting the fusion of traditional European techniques with non-Western subjects.

His technical mastery was exceptional across various media. He was a superb draftsman, favoring sanguine, charcoal, and pastel for their immediacy and ability to capture subtle nuances of form and texture. His paintings, often executed in tempera or oil, are noted for their smooth, sometimes matte finish, precise detail, and sophisticated use of light and shadow to model form. The quality of his line and his understanding of structure have drawn comparisons to Renaissance masters and later Neoclassical proponents like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, demonstrating a lineage of classical draftsmanship.

Parisian Hub, Art Deco, and Stage Design

From the early 1920s, Paris became Iacovleff's primary base. He integrated into the city's vibrant art scene, exhibiting his works regularly and gaining recognition from critics and collectors. His style, with its blend of classicism, exotic subjects, and elegant execution, found resonance within the broader context of the Art Deco movement, which celebrated fine craftsmanship, stylized forms, and influences from diverse global cultures. While not strictly an Art Deco artist in the mold of, say, Tamara de Lempicka, his work shared the era's cosmopolitanism and decorative sensibility.

Beyond his easel painting and drawing, Iacovleff also engaged with the world of theatre, particularly through his connections stemming from the Mir Iskusstva circle. He created portraits of figures associated with the performing arts and occasionally undertook design work for stage productions. This aspect of his career connected him to the legacy of other Russian artists in Paris, such as Léon Bakst and Natalia Goncharova, who had famously revolutionized stage design with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, though Iacovleff's own contributions were less extensive.

Transatlantic Recognition: The Boston Years

Iacovleff's international reputation led to a significant opportunity in the United States. In 1934, he was invited to become the Head of the Department of Painting and Drawing at the prestigious School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He held this position until 1937, bringing his rigorous European academic training and worldly experience to American art education. During his time in the US, he continued to exhibit his work and gained further recognition among American audiences and institutions.

His tenure in Boston represented the peak of his international acclaim. However, this period also coincided with the growing dominance of modernist and abstract styles in the American art world. While respected for his technical prowess and teaching, Iacovleff's steadfast commitment to Neoclassical figuration placed him increasingly outside the prevailing avant-garde trends. His American interlude, therefore, highlights both the breadth of his influence and the shifting artistic landscape of the mid-20th century.

A Network of Artists and Patrons

Throughout his career, Iacovleff moved within a diverse network of artists, patrons, and intellectuals. His most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with Vasily Shukhaev, his "twin" from the Academy days, with whom he shared fundamental artistic principles. His teacher, Dmitry Kardovsky, provided a crucial foundation. His association with Mir Iskusstva connected him to Sergei Diaghilev, Alexandre Benois, Konstantin Somov, and potentially other figures like Nicholas Roerich, another artist known for his extensive travels in Asia.

His travels brought him into contact with patrons like André Citroën, who facilitated the epic expeditions. In Paris, while stylistically distinct, he would have been aware of the major figures of the School of Paris, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. His ethnographic interests paralleled, in subject matter if not style, the work of fellow Russian émigré Zinaida Serebriakova, who also created sensitive portraits during her travels. His commitment to draftsmanship placed him in a lineage including masters like Holbein and Ingres. This network underscores his position within both Russian émigré circles and the broader international art world of his time.

Legacy: Acclaim and Controversy

Alexandre Iacovleff's legacy is multifaceted. He is widely acclaimed as one of the most brilliant draftsmen of the 20th century. His technical virtuosity, particularly in portraiture, remains highly regarded. His work produced during the Citroën expeditions constitutes a unique and invaluable ethnographic and artistic record of cultures undergoing rapid change. His ability to capture individual likeness and dignity with sensitivity earned him praise during his lifetime and continues to be admired. His works command significant prices at auction, as evidenced by the sale of paintings like Intimate Concert at an Hi So, indicating sustained market interest.

However, his artistic position is not without complexity. His adherence to Neoclassicism was seen by some contemporaries, and later critics, as conservative or academic, particularly in contrast to the radical innovations of the avant-garde. Furthermore, viewed through a post-colonial lens, his depiction of non-Western subjects, despite its apparent objectivity and respect, inevitably engages with the complex dynamics of Orientalism and the Western gaze upon other cultures. While celebrated for his skill, his work prompts ongoing discussion about representation, cultural encounter, and the role of the artist as explorer and documentarian.

Final Years and Enduring Influence

After his teaching engagement in Boston, Iacovleff returned to Paris. His health, however, began to decline. He died relatively young, at the age of 50, from stomach cancer in Paris on May 12, 1938. He never returned to live in Russia after the Revolution.

Despite his premature death and the subsequent shift in artistic tastes towards abstraction, Alexandre Iacovleff's work endures. He remains a key figure in 20th-century Russian Neoclassicism and an important artist associated with the visual culture of the Art Deco era. His unique contribution lies in the synthesis of rigorous, classically-derived technique with the subject matter derived from extensive global travel. As an artist who navigated multiple continents and cultures, Iacovleff left behind a powerful and meticulously rendered vision of the world and its diverse peoples during a transformative period in history. His drawings and paintings continue to fascinate viewers with their technical brilliance and their window onto distant lands and times.