Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Russian art, a painter whose profound engagement with history, religion, and the human psyche carved a unique path through the fervent artistic landscape of the 19th century. His journey from academic training to a deeply personal, often controversial, exploration of spiritual themes reflects the intellectual and social currents of his time. Ge was not only a master of realist technique but also a daring innovator, whose work continues to provoke thought and evoke powerful emotional responses. His legacy is one of artistic integrity, relentless questioning, and a profound empathy for the human condition, particularly in moments of moral and spiritual crisis.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge was born on February 27 (February 15, Old Style), 1831, in the city of Voronezh, into a Russian noble family of French descent. His grandfather, a French nobleman, had immigrated to Russia during the tumultuous period of the French Revolution, integrating into Russian society. This French heritage, though generations removed, perhaps contributed a certain outsider's perspective or intellectual curiosity to Ge's later development. Tragically, Ge's early life was marked by loss; his mother passed away when he was still an infant, and his father died shortly thereafter, leaving the young Nikolai to be raised primarily by his devoted serf nanny. This early experience of loss may have subtly shaped his later preoccupation with themes of suffering, compassion, and the search for meaning.

His initial education was not in the arts. He attended the First Kyiv Gymnasium, where he excelled in subjects like physics and mathematics. Following this, he enrolled in the mathematics department at Kyiv University and later transferred to the University of Saint Petersburg, still pursuing scientific studies. However, the allure of art, a passion that had perhaps been simmering beneath the surface, proved too strong. In 1850, at the age of nineteen, Ge made a decisive turn, abandoning his scientific pursuits to enter the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. This was a significant step, moving from the world of empirical facts to the realm of aesthetic expression and historical interpretation.

Academic Training and Italian Sojourn

At the Imperial Academy of Arts, Ge studied under the tutelage of Professor Pyotr Basin, a history painter of the academic school. During these formative years, he was profoundly influenced by the grandeur and dramatic intensity of Karl Bryullov, whose epic painting The Last Day of Pompeii had captivated Russia. Bryullov's mastery of complex compositions, dramatic lighting, and heightened emotion left an indelible mark on many aspiring artists of the period, including Ge. Another significant, albeit more spiritual and philosophical, influence was Alexander Ivanov, whose decades-long labor on The Appearance of Christ Before the People represented a deep, almost obsessive, quest for historical and spiritual truth in religious art. Ivanov's dedication to realism and psychological depth in depicting biblical narratives resonated with Ge's own developing inclinations.

Ge proved to be a talented student. In 1857, he graduated from the Academy, receiving a large gold medal for his painting The Witch of Endor Calling Up the Spirit of the Prophet Samuel. This award was not merely an honor; it came with a coveted scholarship that allowed him to travel and study abroad for six years. Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and a mecca for artists, was his primary destination. He lived and worked in Rome and Florence, immersing himself in the masterpieces of Western art and honing his craft. This period was crucial for his artistic development, exposing him to a wider range of styles and techniques beyond the confines of the Russian academic tradition.

It was in Florence, in 1863, that Ge completed one of his most famous early works, The Last Supper. This painting marked a significant departure from traditional, idealized depictions of the subject. Ge focused on the intense psychological drama of the moment, portraying Christ and his apostles with a stark, human realism. The expressions of doubt, betrayal, and sorrow are palpable. The work caused a sensation when it was exhibited in Saint Petersburg, earning him the title of professor at the Imperial Academy of Arts. Tsar Alexander II was so impressed by its power and originality that he purchased it for his personal collection, a testament to its immediate impact.

A Founder of the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers)

Upon his return to Russia, Ge became increasingly involved with a burgeoning movement that sought to break free from the rigid constraints and perceived elitism of the Imperial Academy. He was one of the founding members of the "Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions" (Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok), more famously known as the Peredvizhniki, or "The Wanderers." Established in 1870, this group aimed to make art more accessible to the wider public by organizing exhibitions that traveled to provincial towns, and to promote a distinctly Russian art, rooted in realism and often addressing social and historical themes relevant to contemporary life.

Ge shared the Peredvizhniki's commitment to realism and their desire to use art as a means of social commentary and moral exploration. His fellow founders and prominent members included Ivan Kramskoi, who was a key ideologue of the movement, Grigory Myasoyedov, Vasily Perov, a master of genre scenes depicting social critique, and later, landscape painters like Ivan Shishkin and Isaac Levitan, and historical painters such as Ilya Repin and Vasily Surikov. Viktor Vasnetsov also became associated with the group, though his work often veered into mythological and folkloric themes.

Ge actively participated in the Peredvizhniki exhibitions. For the very first exhibition in 1871, he presented his historical painting Peter the Great Interrogating Tsarevich Alexei at Peterhof. This work, like The Last Supper, focused on a moment of intense psychological conflict, depicting the tragic confrontation between the reforming Tsar and his conservative son. The painting was lauded for its historical accuracy, dramatic tension, and insightful character portrayal, further solidifying Ge's reputation as a leading figure in Russian historical painting. His role within the Peredvizhniki was significant, not just as an exhibitor but as an artist whose work helped define the movement's engagement with complex historical and ethical questions.

Thematic Focus: History, Religion, and the Human Psyche

Throughout his career, Ge grappled with profound themes, primarily drawn from history and the New Testament. His approach was characterized by a desire to strip away layers of iconographic convention and uncover the human reality and psychological truth of his subjects. He was less interested in dogmatic illustration and more in the moral and spiritual dilemmas faced by individuals at critical junctures.

His historical paintings often explored moments of conflict, power, and conscience. Works like Peter the Great Interrogating Tsarevich Alexei or his later depictions of Pushkin, such as Pushkin in the Village of Mikhailovskoye, delved into the inner lives of significant historical figures, attempting to understand their motivations and the weight of their decisions. He sought to make history relatable, to show the human beings behind the historical events.

However, it was his engagement with religious subjects, particularly the life and passion of Christ, that became the defining feature of his mature work. Ge's interpretation of the Gospels was deeply personal and often radical for its time. He moved away from the idealized, ethereal Christ of traditional religious art, instead presenting a figure who was intensely human, vulnerable, and often tormented by the spiritual and moral struggles he faced. This approach was influenced by contemporary trends in biblical criticism and the broader intellectual climate of an era questioning traditional authorities and seeking a more rational, humanistic understanding of faith. Artists like Alexander Ivanov had paved the way for a more historical and less dogmatic approach to religious painting, and Ge pushed these boundaries further.

Masterworks and Their Reception

The Last Supper (1863) remains one of Ge's most celebrated early achievements. Its stark realism, the dramatic use of chiaroscuro reminiscent of Caravaggio, and the focus on Judas's betrayal and Christ's sorrowful foreknowledge, captivated audiences. The painting's success was immediate, establishing Ge as a major talent.

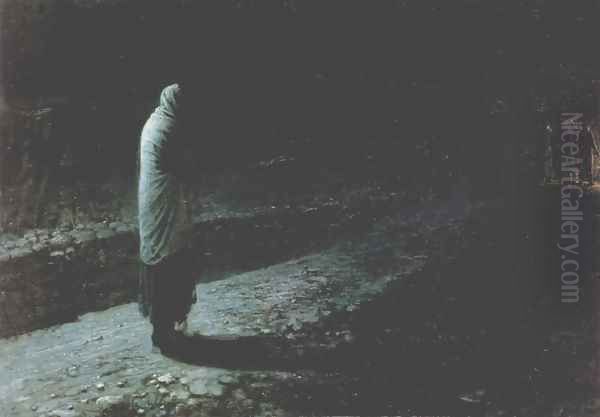

Later in his career, Ge produced a series of works on the Passion of Christ that were far more controversial. The most famous of these is Quod Est Veritas? Christ and Pilate (What is Truth? Christ and Pilate), completed in 1890. In this monumental canvas, Ge presents a stark confrontation between a weary, almost defeated Christ, embodying spiritual truth, and a pragmatic, powerful Pontius Pilate, representing worldly authority. The depiction of Christ—gaunt, disheveled, and profoundly human—shocked many. Critics accused Ge of blasphemy and "nihilism," arguing that he had stripped Christ of his divinity. The painting was even banned from exhibition by the authorities for a time due to its controversial nature.

However, the painting also found powerful defenders, most notably the great writer Leo Tolstoy, with whom Ge had formed a close friendship and shared spiritual affinity. Tolstoy saw in Ge's Christ a profound and authentic representation of Jesus's teachings and suffering, unadorned by ecclesiastical pomp. He praised the work for its psychological depth and its challenge to conventional religious imagery. This painting, perhaps more than any other, encapsulates Ge's mature artistic vision: his relentless search for truth, his willingness to confront difficult questions, and his focus on the internal, spiritual drama of his subjects.

Other significant works from this period include The Judgment of the Sanhedrin: He is Guilty! (1892) and Golgotha (1893), both of which continued his unflinching, psychologically intense exploration of Christ's final days. His sketches for a planned large-scale work, The Resurrection of Christ, also indicate the direction of his late spiritual inquiries, though the final painting was never realized.

The Influence of Leo Tolstoy

The friendship between Nikolai Ge and Leo Tolstoy, which began in the 1880s, was a pivotal relationship in the artist's later life and profoundly influenced his artistic and spiritual direction. Tolstoy, by this time, had undergone his own profound spiritual crisis and conversion, advocating a form of Christian anarchism based on the Sermon on the Mount, emphasizing love, non-resistance to evil, and a simple life. Ge found a deep resonance with Tolstoy's ideas and became one of his most ardent followers and confidants.

Ge spent considerable time at Tolstoy's estate, Yasnaya Polyana, engaging in long discussions with the writer about art, religion, and morality. Tolstoy's emphasis on the ethical core of Christianity, stripped of ritual and dogma, deeply impacted Ge's approach to his "Passion Cycle." Ge sought to portray Christ not as a divine king, but as a moral teacher and a suffering human being whose message had been distorted by established churches. This Tolstoyan influence is evident in the starkness, the psychological intensity, and the anti-clerical undertones of Ge's late religious paintings.

Ge also painted several portraits of Tolstoy, the most famous being the one from 1884, which captures the writer at his desk, deep in thought. These portraits are remarkable for their psychological insight, revealing the complex personality of the great novelist and thinker. The relationship was reciprocal; Tolstoy admired Ge's artistic integrity and his courage in tackling profound spiritual themes in a challenging and unconventional manner. He saw Ge as an artist who truly understood the spiritual crisis of their age.

The Late "Passion Cycle" and Its Controversies

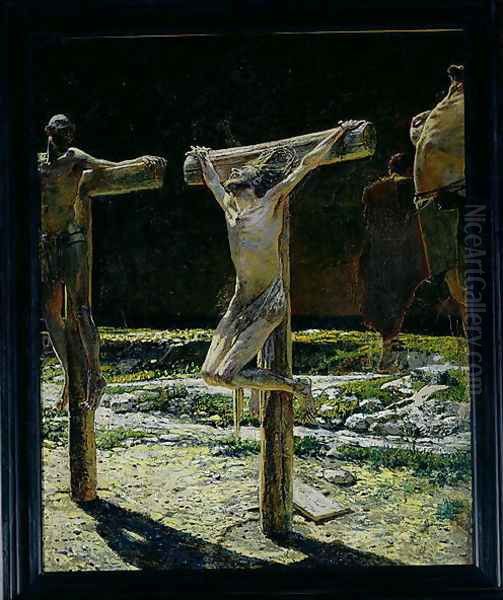

Ge's late works, often collectively referred to as his "Passion Cycle" or "Gospel Cycle," represent the culmination of his spiritual and artistic quest. These paintings, created in the last decade of his life, are characterized by an almost brutal realism, expressive brushwork, and a focus on the raw emotion and psychological torment of Christ and those around him during his final days. Works such as Conscience: Judas (1891), The Judgment of the Sanhedrin: He is Guilty! (1892), Golgotha (1893), and The Crucifixion (various versions, c. 1892-1894) are among the most powerful and unsettling religious paintings in Russian art.

In The Judgment of the Sanhedrin, Christ is depicted as a solitary, illuminated figure facing his accusers, who are shrouded in shadow, their faces contorted with malice or self-righteousness. The painting is a stark commentary on injustice and the corruption of power. Golgotha presents a desolate scene, emphasizing the physical suffering and isolation of the crucifixion. His various treatments of The Crucifixion are particularly harrowing, often focusing on the distorted agony of Christ's body and the grief of the onlookers, rendered with an almost expressionistic intensity. The traditional beauty and serenity often associated with this subject are entirely absent, replaced by a visceral depiction of suffering.

These late works were met with even greater hostility than What is Truth?. The official Orthodox Church and conservative critics condemned them as blasphemous and degrading to the image of Christ. They were seen as an attack on religious tradition and an embodiment of the "nihilism" that many feared was eroding Russian society. The stark, unidealized portrayal of Christ, emphasizing his human suffering to an unprecedented degree, was deeply unsettling to a public accustomed to more conventional and reverent depictions. Despite the official condemnation, these works had a profound impact on younger artists and those who, like Tolstoy, sought a more personal and ethically grounded understanding of Christianity. They cemented Ge's reputation as one of Russia's most original and challenging religious painters.

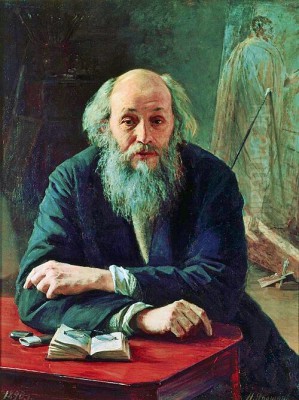

Portraiture: Capturing the Russian Soul

While Ge is best known for his historical and religious paintings, he was also a gifted portraitist. Throughout his career, he painted portraits of prominent figures in Russian culture and society, as well as more intimate depictions of family and friends. His approach to portraiture, much like his approach to other genres, was characterized by a search for psychological truth and a desire to reveal the inner life of his sitters.

His portraits of Leo Tolstoy are, of course, among his most famous. But he also painted other notable figures, including the writer Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, the historian Nikolai Kostomarov, and fellow artists. These portraits are often somber in tone, with a focus on the sitter's face and expression, rendered with a keen eye for individual character. He avoided flattery and superficial embellishment, preferring a more direct and introspective approach. For instance, his portrait of the philanthropist and art collector Pavel Tretyakov, who acquired many of Ge's works for his gallery, shows a man of serious purpose.

Even in his portraits, Ge's interest in moral and intellectual life is evident. He seemed drawn to individuals of strong conviction and complex inner worlds. His ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality and intellectual presence places him among the leading Russian portrait painters of his time, alongside artists like Ivan Kramskoi and later, Valentin Serov and Ilya Repin, who also excelled in capturing the essence of their contemporaries.

Later Years, Artistic Isolation, and Legacy

In 1875, disillusioned with the artistic scene in Saint Petersburg and perhaps seeking a simpler, more spiritually focused life, Ge left the capital and settled on a small farm (khutor) in the Chernigov Governorate (now in Ukraine). This move mirrored Tolstoy's own emphasis on a life closer to the land and removed from the vanities of urban society. Here, he lived a relatively isolated life, dedicating himself to his art, his family, and his spiritual reflections. He continued to paint, focusing increasingly on his religious themes and portraits.

Despite his physical distance from the major art centers, Ge continued to exhibit with the Peredvizhniki and maintained his connections with figures like Tolstoy. His late "Passion Cycle" was largely produced during this period of rural seclusion. The intensity and radicalism of these late works suggest an artist increasingly preoccupied with ultimate questions, unconcerned with public approval or academic conventions.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge passed away on June 13 (June 1, Old Style), 1894, at his farm in Chernigov, at the age of 63. He left behind a body of work that was both celebrated and condemned, but rarely ignored. His influence on subsequent generations of Russian artists was significant, particularly on those who sought to explore spiritual themes with psychological depth and emotional honesty. Artists of the Symbolist movement, such as Mikhail Vrubel, though stylistically different, shared Ge's interest in the spiritual and the mystical, and his willingness to depart from strict realism in pursuit of deeper truths.

Today, Ge's major works are housed in leading museums, primarily the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, as well as the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. His paintings continue to be studied for their artistic power, their historical significance, and their profound engagement with the enduring questions of faith, morality, and the human condition. He is recognized as a pivotal figure who bridged the gap between academic realism and a more modern, psychologically charged approach to art, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Russian culture. His willingness to confront controversy and to follow his own artistic and spiritual convictions makes him a compelling and enduring figure.

Conclusion: An Unflinching Visionary

Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge's artistic journey was one of relentless inquiry and profound integrity. From his early successes within the academic system to his later, more radical explorations of religious themes, he consistently sought to imbue his art with psychological depth and moral seriousness. As a founding member of the Peredvizhniki, he played a crucial role in the development of Russian realism and the movement to make art more relevant and accessible. His close association with Leo Tolstoy further deepened his spiritual quest, leading to a series of late masterpieces that, while controversial, remain some of the most powerful and original religious paintings of the 19th century.

Ge's legacy lies in his unflinching commitment to his artistic vision, his courage to tackle complex and often uncomfortable truths, and his profound empathy for the human experience. He challenged conventions, provoked debate, and ultimately enriched Russian art with a body of work that continues to resonate with its emotional intensity and intellectual depth. He remains a testament to the power of art to explore the deepest questions of human existence.