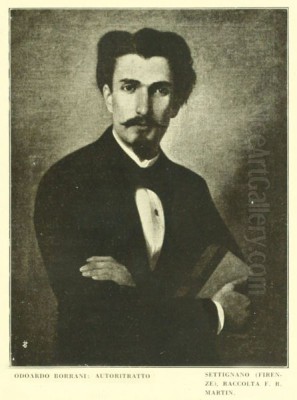

Odoardo Borrani (1833-1905) stands as a significant Italian painter, a key protagonist in the revolutionary Macchiaioli movement that reshaped the landscape of Italian art in the 19th century. Born in Pisa, Borrani spent the majority of his prolific career in Florence, the vibrant heart of this artistic insurgency. His work, characterized by a profound sensitivity to light and an honest depiction of everyday life, contributed significantly to the assertion of a modern artistic vision in Italy, paralleling and sometimes anticipating developments elsewhere in Europe. This exploration delves into his life, his artistic evolution, his pivotal role within the Macchiaioli, and his lasting legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Odoardo Borrani was born on August 22, 1833, in Pisa. His father, a painter of modest renown, likely provided his initial exposure to the world of art. Seeking greater opportunities, the Borrani family relocated to Florence, a city teeming with artistic heritage and burgeoning creative energy. It was here, in 1851, that the young Odoardo enrolled at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts). At the Accademia, he would have been immersed in the prevailing academic traditions, which emphasized meticulous draughtsmanship, historical subjects, and idealized forms, drawing heavily from classical and Renaissance masters.

During his formative years at the Accademia, Borrani studied under figures like Gaetano Bianchi, and was exposed to the works and teachings influenced by neoclassical masters such as Antonio Canova and the purist sensibilities of Lorenzo Bartolini. While these academic foundations provided him with essential technical skills, Borrani, like many of his contemporaries, began to feel constrained by the rigid doctrines of the institution. The desire for a more direct, truthful engagement with reality was stirring among a new generation of artists.

The Caffè Michelangelo and the Birth of the Macchiaioli

The intellectual and artistic ferment of Florence in the mid-19th century found its nexus at the Caffè Michelangelo. This bustling café became the unofficial headquarters for a group of young, rebellious artists, writers, and patriots who gathered to debate art, politics, and the future of Italy. Borrani was a regular and active participant in these impassioned discussions. It was within this crucible of revolutionary ideas that the Macchiaioli movement was forged.

The term "Macchiaioli" was initially a derogatory one, coined by a critic in 1862, derived from the Italian word "macchia," meaning "spot" or "stain." It referred to the artists' technique of using bold patches (macchie) of color and contrasting tones to capture the immediate effects of light and shadow, often painted directly from nature (en plein air). This approach was a radical departure from the smooth, polished finish and linear precision favored by the Academy. The Macchiaioli sought to convey a sense of immediacy and realism, focusing on the visual truth of their subjects rather than idealized or romanticized interpretations.

Borrani, alongside artists like Telemaco Signorini, Vincenzo Cabianca, Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, Cristiano Banti, and Giuseppe Abbati, became a leading proponent of this new vision. These artists shared a common dissatisfaction with academic conventions and a fervent desire to create an art that was both modern and distinctly Italian. Their subjects often included everyday scenes, rural landscapes, and portraits, rendered with a fresh, unvarnished honesty. The influence of French Realists like Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon School painters such as Camille Corot, who also championed direct observation of nature, was palpable, though the Macchiaioli developed their own unique visual language.

Borrani's Artistic Style: Light, Life, and Landscape

Odoardo Borrani's art is distinguished by its meticulous observation, its subtle yet powerful use of light, and its empathetic portrayal of ordinary life. He was particularly adept at capturing the interplay of light and shadow, whether in sun-drenched Tuscan landscapes or in the quiet intimacy of domestic interiors. His commitment to plein air painting allowed him to study these effects firsthand, resulting in works that possess a remarkable sense of atmosphere and authenticity.

His landscapes often depict the serene beauty of the Tuscan countryside, with its rolling hills, ancient farmhouses, and distinctive light. Works like Antica Porta San Gallo (Ancient San Gallo Gate, c. 1880) and Antica Porta Prato (Ancient Prato Gate, c. 1880) showcase his ability to blend architectural detail with atmospheric effects, capturing a sense of history and place. These paintings are not merely topographical records but are imbued with a quiet poetry, reflecting Borrani's deep connection to his surroundings.

Borrani also excelled in depicting interior scenes, often focusing on women engaged in domestic activities. These works are characterized by their tranquil mood, their careful composition, and their sensitive rendering of light filtering through windows or illuminating figures within a room. He treated these humble subjects with a dignity and respect that elevated them beyond mere genre scenes, reflecting a broader Realist concern with the lives of ordinary people. His brushwork, while adhering to the macchia principle of distinct color patches, could also be refined and delicate, particularly in his treatment of figures and textures.

Key Works: Narratives of Art, Politics, and Daily Existence

Several of Odoardo Borrani's paintings stand out as iconic representations of his artistic concerns and the spirit of his time. One of his most celebrated works is Cucitrici di camicie rosse (Women Sewing Red Shirts), painted in 1863. This painting depicts a group of women diligently sewing the red shirts worn by Garibaldi's volunteers during the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. The work is a powerful testament to the patriotic fervor of the era and the crucial, often unsung, role played by women in the struggle for national independence. The intimate interior setting, the focused concentration of the women, and the symbolic power of the red fabric combine to create a poignant and historically significant image.

Another important facet of Borrani's oeuvre is his engagement with historical and contemporary events. His painting 26 Aprile 1859 a Firenze (April 26, 1859, in Florence) captures a pivotal moment in the Risorgimento, depicting the popular uprising that led to the departure of Grand Duke Leopold II from Tuscany. Such works demonstrate Borrani's commitment to an art that was not only aesthetically innovative but also socially and politically engaged. Similarly, La Morte di Jacopo de' Pazzi (The Death of Jacopo de' Pazzi, 1864) delves into Florentine history, portraying a dramatic episode from the Pazzi Conspiracy against the Medici.

His painting L'interno dell'Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze (Interior of the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence) offers a glimpse into the very institution where he received his early training, perhaps with a touch of the Macchiaioli's critical perspective on academic practices. The Wheat Harvest in Castiglioncello is another notable work, showcasing his ability to depict rural labor with dignity and a keen eye for the effects of sunlight on the landscape and figures. These works, varied in subject matter, are united by Borrani's consistent pursuit of visual truth and his mastery of light and color.

The Piagentina School: A Rural Retreat

In the 1860s, Borrani, along with fellow Macchiaioli artists Telemaco Signorini, Silvestro Lega, Giuseppe Abbati, and Raffaello Sernesi, became associated with what is sometimes referred to as the "Scuola di Piagentina" (Piagentina School). This was not a formal institution but rather a shared artistic endeavor centered around the rural area of Piagentina (or Pergentina), a tranquil suburb just outside Florence's city walls. Here, these artists sought refuge from the urban bustle and dedicated themselves to painting the quiet beauty of the countryside and the simple rhythms of rural life.

The works produced during this period are often characterized by a serene, contemplative mood and a heightened sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere. Borrani's paintings from this time frequently feature peaceful landscapes, rustic dwellings, and figures engaged in quiet, everyday tasks. The Piagentina period marked a phase of intense artistic exploration and camaraderie, where the artists mutually reinforced their commitment to plein air painting and the principles of the macchia. The critic Diego Martelli, a staunch supporter and theorist of the Macchiaioli, was also closely associated with this group, often visiting and encouraging their endeavors.

Political Engagement and the Risorgimento

The Macchiaioli movement was inextricably linked to the political and social currents of its time, particularly the Risorgimento. Many of the artists, including Borrani and Signorini, were ardent patriots who actively participated in or supported the struggle for Italian unification and independence. Borrani, for instance, served as a volunteer in the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859.

This patriotic engagement infused their art with a sense of purpose and a desire to create a truly Italian modern art, free from foreign domination and academic stagnation. Their choice of subjects—often drawn from contemporary Italian life, historical events related to the Risorgimento, or the landscapes of their homeland—reflected this national consciousness. Works like Borrani's Cucitrici di camicie rosse are direct expressions of this political commitment, celebrating the collective effort towards a unified Italy. The Macchiaioli saw their artistic revolution as part of a broader cultural and political renewal for the nation.

Collaborations and Artistic Circle

Odoardo Borrani was an integral part of a close-knit artistic community. His collaborations and friendships were crucial to his development and to the vitality of the Macchiaioli movement. His closest associates included Telemaco Signorini and Vincenzo Cabianca, with whom he shared early explorations and founded the Piagentina School. Giovanni Fattori, often considered one of the greatest of the Macchiaioli, was another key figure in this circle, known for his powerful depictions of military life and Tuscan landscapes.

Silvestro Lega, with his sensitive portrayals of domestic life and female figures, also worked closely with Borrani, particularly during the Piagentina period. Giuseppe Abbati, whose promising career was cut short, and Cristiano Banti, a collector and painter who provided crucial support to the group, were also important members of Borrani's artistic milieu. Other artists associated with or influenced by the Macchiaioli, such as Serafino De Tivoli, Adriano Cecioni (who was also a sculptor and influential critic), and later painters like Giovanni Boldini (though Boldini's style evolved differently), contributed to the rich artistic environment of Florence.

While direct, deep friendships with international figures like John Singer Sargent or Camille Pissarro are not as extensively documented for Borrani as for some other Italian artists of the period, the Macchiaioli were certainly aware of broader European artistic trends. Their innovations ran parallel to movements like French Realism and the Barbizon School, and they can be seen as Italian precursors to Impressionism, sharing a common interest in light, color, and capturing the fleeting moment. The Macchiaioli, including Borrani, created a distinctly Italian response to the challenges of modern art.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Odoardo Borrani continued to paint throughout his life, remaining committed to the principles that had defined his career. While the Macchiaioli movement as a cohesive group eventually dispersed, its impact on Italian art was profound and lasting. Borrani's later works continued to explore his favored themes of landscapes and genre scenes, often imbued with a sense of quiet melancholy or nostalgia. He also dedicated himself to teaching and art restoration.

One of his later notable works, Estasi di Santa Teresa (Ecstasy of Saint Teresa), painted in 1883 and now housed in the Pitti Palace, Florence, demonstrates his versatility in handling religious themes, albeit rendered with his characteristic attention to realistic detail and emotional depth.

Odoardo Borrani passed away in Florence on September 14, 1905. His legacy lies in his significant contribution to one of Italy's most important 19th-century art movements. As a founding member of the Macchiaioli, he helped to break the stranglehold of academicism and to pave the way for a modern, observational approach to painting. His works are admired for their technical skill, their honest portrayal of Italian life and landscape, and their masterful handling of light. Borrani's paintings offer a luminous window into the world of 19th-century Italy, capturing its beauty, its struggles, and its aspirations with enduring sensitivity and artistic integrity. His art continues to be studied and appreciated for its role in the broader narrative of European modernism.