Silvestro Lega stands as one of the most significant and sensitive painters of 19th-century Italy. An artist whose life was interwoven with the passionate political and artistic currents of his time, Lega's journey from academic tradition to the revolutionary aesthetics of the Macchiaioli group charts a course of profound personal and artistic development. His works, characterized by their intimate portrayal of domestic life, serene landscapes, and poignant human emotion, offer a unique window into the soul of a nation undergoing transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on December 8, 1826, in Modigliana, a small town near Forlì in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, Silvestro Lega came from a relatively affluent landowning family. This background provided him with the means to pursue an artistic education, a path he embarked upon with youthful enthusiasm. In 1843, he moved to Florence, the vibrant heart of Tuscan art, to enroll at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti.

At the Accademia, Lega studied under several notable masters who shaped his early artistic sensibilities. These included Benedetto Servolini, a painter known for his historical and religious subjects, and Tommaso Gazzarini. He also received instruction from Luigi Mussini, a leading figure of the Purist movement in Siena, which advocated a return to the clarity and simplicity of early Renaissance art, particularly the works of artists like Fra Angelico and Perugino. This Purist influence, with its emphasis on precise drawing and serene compositions, can be discerned in Lega's early works.

During these formative years, Lega diligently honed his technical skills, mastering the academic principles of drawing, composition, and color. His initial output reflected the prevailing tastes of the time, often focusing on historical or biblical themes rendered with a meticulous, polished finish. However, the seeds of a more personal and observational style were already beginning to germinate, awaiting the right catalysts to fully bloom.

The Call of Patriotism: Involvement in the Risorgimento

The mid-19th century in Italy was a period of intense political fervor, dominated by the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification and independence from foreign rule. Like many young idealists of his generation, Silvestro Lega was deeply moved by the patriotic cause. His artistic studies were interrupted by his active participation in the struggles for national liberation.

In 1848 and 1849, Lega volunteered to fight in the campaigns for Italian independence. He served as a Garibaldino, a follower of the charismatic revolutionary leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. This direct involvement in the military and political upheavals of the era profoundly impacted Lega. It exposed him to the realities of conflict, the camaraderie of shared struggle, and the fervent desire for a unified Italian nation. These experiences undoubtedly broadened his worldview and instilled in him a deeper connection to the everyday lives and aspirations of his countrymen, themes that would later resonate powerfully in his art.

Following his military service, Lega returned to Florence in 1850 to continue his artistic pursuits. He furthered his studies under Antonio Ciseri, a Swiss-Italian painter respected for his historical paintings and portraits, which combined academic precision with a more naturalistic approach to light and character. Under Ciseri's guidance, Lega refined his technique, and one notable work from this period is Il dubbio di Giovanni (John's Doubt), showcasing his growing command of narrative and psychological expression within a traditional framework.

The Macchiaioli Revolution: A New Vision for Italian Art

The 1850s and 1860s witnessed a radical shift in the Florentine art scene with the emergence of the Macchiaioli. This group of young painters, who frequented the Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence as their intellectual and artistic hub, sought to break free from the rigid conventions of academic art. The name "Macchiaioli," initially a derogatory term meaning "blotchers" or "stainers," was derived from their innovative technique of using "macchie" – broad, distinct patches or spots of color and chiaroscuro – to capture the immediate impression of light and form.

The Macchiaioli advocated for painting dal vero (from life) and en plein air (outdoors), principles that paralleled the concerns of the Barbizon School and, later, the Impressionists in France. They rejected the idealized subjects and polished finish of academic painting, turning instead to the depiction of everyday life, contemporary landscapes, and scenes reflecting the social and political realities of their time. Key figures in this movement included Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, Adriano Cecioni (who was also a prominent critic of the group), Vincenzo Cabianca, Cristiano Banti, Odoardo Borrani, Raffaello Sernesi, and Giuseppe Abbati.

Silvestro Lega, initially somewhat reserved, became increasingly drawn to the Macchiaioli's revolutionary ideas and practices around the late 1850s and early 1860s. He found their commitment to truthfulness, their bold use of color, and their focus on contemporary subjects deeply compelling. His association with the group marked a decisive turning point in his artistic career, leading him away from academic Purism towards a more vibrant and personal form of realism.

Lega's Unique Contribution to the Macchiaioli

While fully embracing the core tenets of the Macchiaioli movement, Silvestro Lega developed a distinct artistic voice within it. His interpretation of the macchia technique was often more nuanced and lyrical than that of some of his more overtly robust contemporaries like Fattori. Lega's paintings, while employing strong contrasts of light and shadow, often retained a sense of classical structure and compositional harmony, perhaps a lingering influence from his Purist training.

His most celebrated period is often considered to be from the mid-1860s to the early 1870s, particularly during his time spent with the Batelli family in their villa near Perignano. This period saw the creation of some of his most iconic works, characterized by an atmosphere of serene domesticity, gentle human interaction, and a profound sensitivity to the effects of light. Lega's paintings from this era often depict women engaged in quiet activities – reading, sewing, playing music, or conversing in sun-dappled gardens and tranquil interiors.

Unlike some Macchiaioli who focused on grander historical narratives of the Risorgimento or the ruggedness of peasant life, Lega excelled at capturing the intimate, poetic moments of bourgeois family life. His figures are rendered with a quiet dignity and psychological depth, conveying a sense of warmth and empathy. His use of color became richer and more luminous, and his compositions achieved a remarkable balance between formal clarity and naturalistic observation.

Key Themes and Representative Works

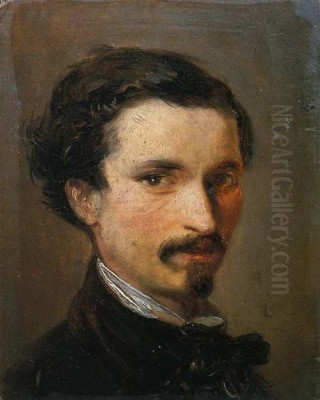

Silvestro Lega's oeuvre explores several recurring themes, each handled with his characteristic sensitivity and technical skill. His most significant contributions lie in his depictions of domestic interiors, portraits, and landscapes, often imbued with a quiet, contemplative mood.

Portraits and Domestic Scenes

Lega's portraits and domestic scenes are perhaps his most beloved works. He had a remarkable ability to capture not just the likeness of his sitters but also their inner lives and the subtle dynamics of their relationships.

One of his most famous masterpieces is Il Pergolato (The Pergola), also known as Un dopopranzo (An Afternoon Meal), painted around 1868. This iconic work depicts a group of women, members of the Batelli family, enjoying a moment of leisure under a sun-dappled pergola. The play of light filtering through the leaves, the relaxed postures of the figures, and the overall atmosphere of tranquil sociability make it a quintessential example of Lega's mature style and the Macchiaioli's interest in capturing fleeting moments of everyday life. The composition is carefully structured, yet the scene feels entirely natural and unposed.

Another significant work is La Visita (The Visit, c. 1868). This painting portrays two women in a modestly furnished interior, engaged in a quiet conversation. Lega masterfully uses light and shadow to define the space and highlight the figures, creating an atmosphere of intimacy and gentle contemplation. The subtle emotional undertones and the careful rendering of textures and details are characteristic of his approach.

Il canto dello stornello (The Song of the Starling, 1867) is another celebrated piece. It shows three young women gathered around a piano in a sunlit room. One plays the instrument while the others listen intently or sing along. The painting beautifully captures a moment of shared cultural enjoyment and domestic harmony. Lega's skill in depicting the interplay of light, the textures of fabrics, and the expressive faces of the figures is evident. The work radiates a sense of warmth and refined sensibility.

Dama in preghiera (Lady in Prayer) showcases Lega's mastery of light and color to convey a mood of quiet devotion. The focused light on the praying figure against a darker background emphasizes her piety and creates a powerful, intimate image.

Landscapes and Outdoor Scenes

While renowned for his interior scenes, Lega also produced exquisite landscapes, often imbued with the same sense of serenity and careful observation found in his genre paintings. He frequently painted en plein air, capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Tuscan countryside.

His landscapes often feature as backdrops to his figural compositions, as seen in Il Pergolato, where the lush garden setting is integral to the painting's charm. However, he also created pure landscapes that demonstrate his sensitivity to the nuances of nature. These works, like those of his Macchiaioli colleagues, emphasize the direct observation of reality, using bold patches of color to convey the effects of sunlight and shadow on the terrain.

Gabbrigiana. La bella del Gabbro (The Beauty of Gabbro / The Girl from Gabbro) is a notable work that combines portraiture with landscape. It depicts a young woman from the village of Gabbro, set against the backdrop of the local scenery. The painting showcases Lega's ability to integrate figures seamlessly into their environment, capturing both the character of the individual and the spirit of the place.

Historical and Political Subjects

Given his involvement in the Risorgimento, it is not surprising that Lega also addressed historical and political themes, though perhaps less frequently than some of his contemporaries like Giovanni Fattori, who was renowned for his battle scenes.

Lega's most famous work in this vein is Mazzini morente (Mazzini on his Deathbed), painted in 1873. This poignant portrait depicts Giuseppe Mazzini, one of the intellectual fathers of Italian unification, during his final moments. Lega, who deeply admired Mazzini, created a somber and respectful image that conveys the gravity of the occasion and the nation's loss. The painting is a powerful testament to Lega's patriotic sentiments and his ability to imbue historical subjects with profound human emotion. It stands as a significant document of the Risorgimento era.

Artistic Style and Evolution

Silvestro Lega's artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career, reflecting his personal journey and the changing artistic landscape of 19th-century Italy. His early training instilled in him a respect for academic principles, particularly the clarity of line and balanced composition associated with Purism. This foundation provided a structural solidity that often remained even as he embraced more radical techniques.

The crucial turning point was his adoption of the Macchiaioli aesthetic. He learned to use macchie – distinct patches of color and tone – to construct forms and represent the effects of light. This technique allowed for a more immediate and vibrant depiction of reality, moving away from the smooth, blended surfaces of academic painting. Lega's application of the macchia was often characterized by a refined sensibility; his color harmonies could be both bold and subtle, and his handling of light was particularly masterful, creating convincing illusions of depth and atmosphere.

While the Macchiaioli are sometimes seen as Italian precursors or parallels to French Impressionism, there are important distinctions. The Macchiaioli, including Lega, generally retained a stronger emphasis on form, volume, and drawing compared to the more dissolution of form into light and color seen in many Impressionist works. Lega's figures, for instance, always possess a tangible solidity.

In his later years, particularly after the emotional and financial hardships he faced, Lega's style underwent further changes. Some art historians note a potential influence from Impressionism in his later works, characterized by a freer brushstroke and a continued exploration of light. However, his output became more sporadic due to failing eyesight and declining health. Despite these challenges, his commitment to capturing the truth of his subjects, whether a sunlit garden or the quiet dignity of a human face, remained a constant.

Collaborations and Artistic Circle

Silvestro Lega was an integral part of a vibrant artistic community. His closest associations were, naturally, with fellow Macchiaioli painters. He shared ideas, exhibited with, and often painted alongside figures like Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini. These artists, along with Odoardo Borrani, Raffaello Sernesi, Giuseppe Abbati, Vincenzo Cabianca, and Cristiano Banti, formed the core of the movement, mutually influencing and supporting each other's artistic explorations. The Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence served as their informal headquarters, a place for lively debate and the forging of artistic manifestos.

Lega's relationship with Odoardo Borrani was particularly close for a time. In 1875, the two artists collaborated to open a commercial art gallery in Florence, hoping to promote their work and that of their colleagues. Unfortunately, the venture was short-lived due to financial difficulties, closing within a year. This endeavor, however, highlights their entrepreneurial spirit and their desire to create an alternative to the established academic art system.

The critic Diego Martelli was another crucial figure in the Macchiaioli circle, providing intellectual support and championing their work. Lega, like other members of the group, benefited from Martelli's advocacy.

Beyond his professional collaborations, Lega formed deep personal connections that significantly influenced his art. His long and close friendship with the Batelli family is paramount. He lived with them for extended periods at their country estate in Perignano, and it was during this time that he produced many of his most serene and celebrated domestic scenes, such as Il Pergolato and Il canto dello stornello. Virginia Batelli and her children became frequent subjects, and the atmosphere of their home provided the perfect setting for Lega's intimate and lyrical style.

He also maintained connections with other artists and patrons, such as Angelo Cardelli, at whose family gatherings he would engage in artistic discussions, further enriching his intellectual and social life within the artistic community.

Later Years, Challenges, and Legacy

The 1870s marked a period of increasing hardship for Silvestro Lega. The death of Virginia Batelli in 1870 was a profound personal loss, and the subsequent dispersal of the Batelli family meant the end of the idyllic Perignano period that had been so artistically fruitful. He also faced growing financial difficulties, as the Macchiaioli's art, while revolutionary, did not always find ready buyers in a market still largely dominated by academic tastes.

A more devastating blow came in the late 1870s when Lega began to suffer from a serious eye disease, reportedly stemming from a lung condition. His eyesight deteriorated rapidly, and by the early 1880s, he was almost completely blind. This cruel affliction effectively ended his painting career at a relatively early age. Though he made attempts to resume work in his later years, his failing vision made sustained artistic production impossible.

Silvestro Lega spent his final years in increasing poverty and ill health. He passed away on September 21, 1895, at the Hospital of San Giovanni di Dio in Florence. During his lifetime, his work, like that of many Macchiaioli, did not achieve widespread fame or financial success. However, posthumous exhibitions and a growing appreciation for 19th-century Italian art have led to a significant re-evaluation of his contributions.

Today, Silvestro Lega is recognized as one of the leading figures of the Macchiaioli movement and a master of Italian Realism. His paintings are admired for their technical skill, their poetic sensitivity, and their honest portrayal of human life and emotion. Works like Il Pergolato, La Visita, and Il canto dello stornello are considered masterpieces of 19th-century Italian art, celebrated for their harmonious compositions, luminous color, and profound empathy. Lega's ability to capture the quiet dignity of everyday existence and the subtle nuances of light and atmosphere ensures his enduring place in the history of art.

Conclusion

Silvestro Lega's artistic journey reflects the broader cultural and political transformations of 19th-century Italy. From his academic beginnings to his embrace of the Macchiaioli revolution, he consistently sought a truthful and personal means of expression. His deep engagement with the Risorgimento, his intimate connection with the Batelli family, and his unwavering dedication to his craft, even in the face of adversity, all shaped his unique artistic vision.

His legacy lies in a body of work that combines formal rigor with tender observation, capturing moments of quiet beauty and profound humanity. Through his serene domestic scenes, his sensitive portraits, and his luminous landscapes, Silvestro Lega offered a lyrical and enduring perspective on the life of his times, securing his position as a pivotal and much-loved painter in the rich tapestry of Italian art.