An Enduring Figure in German Art

Christian Rohlfs stands as a significant and highly regarded figure in the landscape of German art, particularly celebrated as one of the pioneering forces behind Expressionism. Spanning a long and remarkably productive life from 1849 to 1938, Rohlfs navigated the turbulent currents of artistic change in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leaving behind a rich legacy in painting and printmaking, and even exploring sculpture. His journey was one of constant evolution, moving from the detailed observations of Naturalism through the light-filled canvases of Impressionism to the raw, emotive power of Expressionism.

Rohlfs's life story is also one of resilience. Faced with a significant physical disability early in life and later confronting the oppressive cultural policies of the Nazi regime, he remained dedicated to his artistic vision. His work, characterized by vibrant color, innovative techniques, and deep emotional resonance, continues to be studied and admired, securing his place as a vital contributor to modern art history.

Formative Years and the Call to Art

Born on November 22, 1849, in Groß Niendorf, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia (now in Poland), Christian Rohlfs's path to art was unconventional. It wasn't an early apprenticeship but a period of convalescence that sparked his creative journey. At the age of 15, a serious fall from a tree resulted in a leg injury that would eventually necessitate amputation due to infection. During the long recovery period, confined to bed, Rohlfs began to draw and paint, discovering a profound talent and passion that would define his life.

Recognizing his potential, he was encouraged to pursue formal training. In 1867, he enrolled at the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School in Weimar (Kunstschule Weimar), a respected institution where he received a solid academic grounding. He later continued his studies in Berlin. His early artistic output reflected this training, primarily focusing on Naturalistic landscapes and detailed renderings, showing a competence in traditional styles influenced perhaps by mid-century movements like the Barbizon School's approach to landscape.

Embracing Modernity: Impressionism and Beyond

As the art world shifted, so did Rohlfs's style. While initially rooted in Naturalism, he became increasingly aware of and receptive to the revolutionary changes emanating from France. The influence of Impressionism began to permeate his work, leading him towards a lighter palette, a greater interest in capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, and looser brushwork. Works from the late 1880s, such as his Winter Landscape (dated variously as 1887 or 1889), demonstrate this evolving sensibility.

However, it was the subsequent wave of Post-Impressionism that had a more profound and lasting impact. Rohlfs was particularly captivated by the work of Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh's intense emotionalism, expressive use of color, and dynamic brushwork resonated deeply with Rohlfs's own developing artistic temperament. The influence of Neo-Impressionism, with its systematic application of color, also played a role. Furthermore, the psychologically charged works of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch provided another crucial stimulus, pushing Rohlfs further towards subjective expression over objective representation. His painting St. Patroclus in Soest (1905-1906) stands as an example of this transitional phase, where architectural form begins to yield to expressive color and light.

Hagen, Osthaus, and the Expressionist Dawn

A pivotal chapter in Rohlfs's life and career began in 1901 when he moved to Hagen. This move was facilitated by the influential patron Karl Ernst Osthaus, a passionate advocate for modern art and the founder of the Folkwang Museum in Hagen (later relocated to Essen). Osthaus provided Rohlfs with crucial support, including studio space and opportunities to engage with the latest artistic developments. The environment in Hagen, centered around the progressive vision of Osthaus and the Folkwang, proved immensely stimulating.

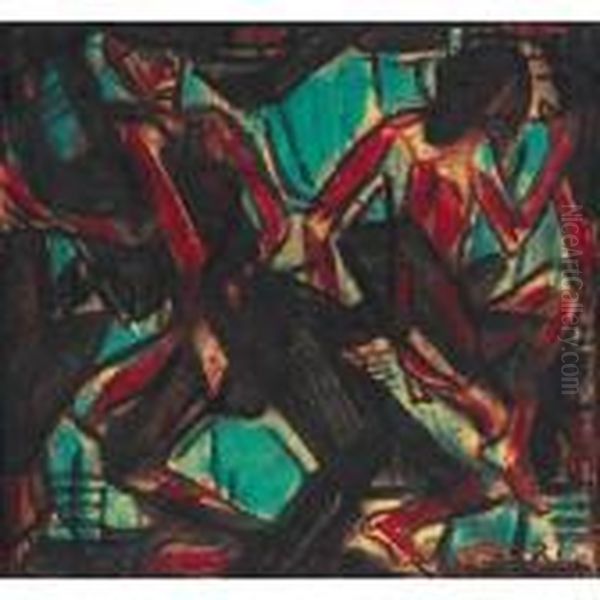

The definitive catalyst for Rohlfs's full embrace of Expressionism occurred in 1907. That year, he encountered an exhibition of works by the artists' group Die Brücke (The Bridge) at the Folkwang Museum. The raw energy, bold colors, and distorted forms employed by artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Rohlfs's future friend Emil Nolde struck a powerful chord. Inspired by their radical departure from convention and their focus on inner feeling, Rohlfs decisively shifted his style. He became, in spirit if not formal membership, aligned with the core tenets of German Expressionism.

His connection with Emil Nolde, another somewhat older artist associated with Die Brücke, developed into a significant friendship. This interaction further solidified Rohlfs's commitment to an art defined by intense, often non-naturalistic color, simplified or distorted forms drawn from subjective experience, and a powerful emotional charge. He was now firmly on the path that would define his mature work.

The Height of Expression: Color, Form, and Emotion

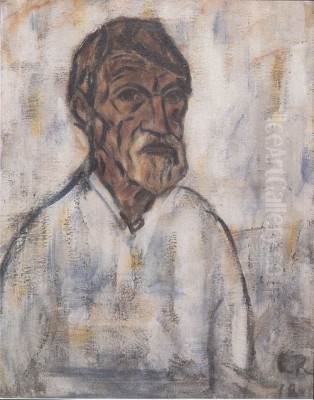

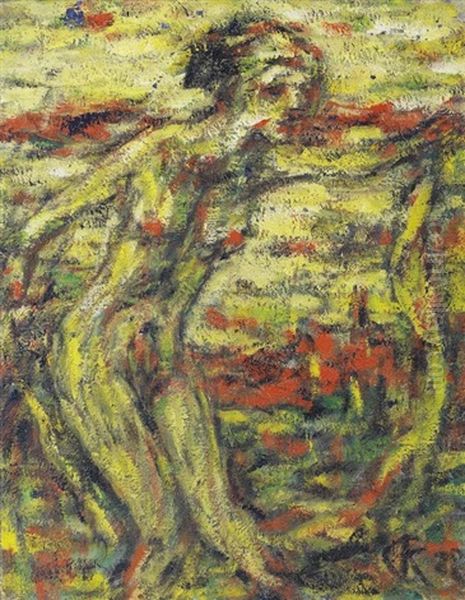

In his mature Expressionist phase, Christian Rohlfs developed a highly personal and recognizable style. Color became paramount, used not merely to describe the visible world but to convey emotion and create visual impact. He employed vibrant, often clashing hues with remarkable freedom, exploring combinations like the acid greens, yellows, and vermilions noted in later works such as Tänzerin mit Schleier (Dancer with Veil). His palette was bold, experimental, and deeply expressive.

Form, too, was subjected to the demands of feeling. Rohlfs simplified shapes, elongated or distorted figures, and flattened perspective to enhance the emotional content of his work. While rarely fully abstract, his later paintings often pushed representation to its limits, blurring the lines between the subject and the energetic application of paint. His brushwork was vigorous and direct, leaving visible traces of the creative process.

His subject matter remained diverse, though often revisited with his new expressive intensity. He continued to paint landscapes, transforming familiar scenes through the lens of subjective experience. Cityscapes, particularly views of the medieval town of Soest, were a recurring motif, rendered with dramatic angles and heightened color, as seen in Medieval Town of Soest (1928). Figures, including dancers like the Gentleman in Tails and Creole Dancer (c. 1927) and biblical subjects, were imbued with psychological depth. Nature, especially flowers and trees like the Old Lime Tree (1928), provided opportunities for exploring vibrant color and organic forms. Works like Der rote Narr (The Red Fool, possibly c. 1919) showcase his experimental handling of materials and large formats.

Innovation in Black and White: Rohlfs the Printmaker

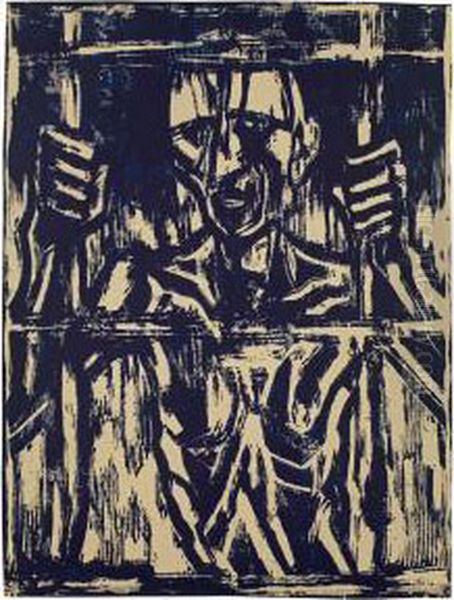

Alongside his powerful paintings, Christian Rohlfs made significant contributions as a printmaker. He produced a substantial body of work in this medium, estimated at around 185 prints, primarily utilizing woodcut and linocut techniques, though sources also mention experiments with oil or tempera prints. His approach to printmaking mirrored the boldness and expressiveness of his painting.

He embraced the inherent qualities of the woodcut, exploiting the potential for strong contrasts, stark lines, and simplified, powerful forms. His designs were often characterized by their graphic intensity and raw energy. Rohlfs used printmaking not just as a reproductive medium but as a primary means of artistic expression, exploring themes with a directness and force well-suited to black and white.

Several of his prints stand as iconic examples of German Expressionist graphic art. Works created around the end of World War I, such as Der Sklavenhalter (The Slaveholder, 1918) and Der Gefangene (The Prisoner, 1918), tackle themes of power, oppression, and psychological suffering with stark imagery and rough-hewn lines. Death as Juggler (1918-1919), depicting a skeleton manipulating smaller skulls, offers a macabre yet potent metaphor for mortality, possibly reflecting the era's turmoil. Other prints, like Dialogue, Couple, Wanderer, and Three Kings, delve into fundamental aspects of human relationships and social conditions.

Acclaim, Marriage, and the Shadow of Nazism

Rohlfs continued to work prolifically into his later years. His personal life saw a significant change in 1916 when, in his late 60s, he married a younger woman, an event sources suggest brought new energy to his life and art. He remained based primarily in Hagen, maintaining his connection with the Folkwang Museum and the artistic community there.

His contributions were recognized during his lifetime. He held teaching positions, including possibly at Weimar early on and certainly through his association with the Folkwang in Hagen, influencing younger artists. He was elected to the prestigious Prussian Academy of Arts. A major honor came in 1929 when, for his 80th birthday, the Christian Rohlfs Museum was established in Hagen, dedicated to preserving and showcasing his work.

However, the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933 cast a dark shadow over Rohlfs's later years. Like many modern artists whose work did not conform to the Nazis' narrow, reactionary aesthetic ideals, Rohlfs was targeted. Expressionism was officially condemned as "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst). In 1933, he was expelled from the Prussian Academy of Arts. His work was vilified, and in the notorious purge of German museums in 1937-38, a staggering 412 of his artworks were confiscated from public collections, many likely sold abroad or destroyed.

In 1937, Rohlfs, along with numerous other leading modern artists in Germany – including his friend Emil Nolde, the Brücke artists Kirchner, Heckel, and Schmidt-Rottluff, and figures like Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee – was effectively banned from working and exhibiting. This persecution marked a tragic end to a long career dedicated to artistic freedom and innovation.

Enduring Influence: Rohlfs' Place in Art History

Christian Rohlfs died in Hagen on January 8, 1938, at the age of 88, shortly after the ban on his work was imposed. He did not live to see the end of the Nazi regime or the eventual restoration of his artistic reputation. After World War II, however, his significance was re-evaluated, and he was rightfully recognized as a major figure in German Expressionism and modern art.

His legacy is multifaceted. He stands as a key pioneer who helped shape the course of Expressionism in Germany, developing a unique and powerful style characterized by its emotional intensity and mastery of color. His innovative work in printmaking, particularly woodcut, represents a significant contribution to the graphic arts of the 20th century. His life story, marked by early adversity and later persecution, speaks to a profound dedication to his artistic vision.

While specific names of artists he directly taught are not always highlighted, his role as an educator and his association with the Folkwang Museum undoubtedly influenced the development of modern art in Germany. Today, his works are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Folkwang Museum in Essen, the Pinakothek der Moderne and the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, among many others. His paintings and prints continue to command attention and respect on the international art market, a testament to their enduring power and artistic value. Christian Rohlfs remains a compelling figure, an artist whose long journey through changing styles culminated in a deeply personal and historically significant body of Expressionist work.