Alexei von Jawlensky (March 13, 1864 – March 15, 1941) stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century European art. A Russian-born painter who found his artistic voice primarily in Germany, Jawlensky became a key exponent of Expressionism, celebrated for his intensely colourful, emotionally charged portraits and his later, deeply spiritual abstract heads. His life spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval and innovation, and his work reflects a fascinating synthesis of Russian traditions, French modernism, and German Expressionist fervour. His journey took him from the military barracks of Tsarist Russia to the heart of the Munich avant-garde, through the trials of exile and the persecution of the Nazi regime, leaving behind a powerful legacy of art that continues to resonate with viewers today.

From Russia's Steppes to Artistic Awakening

Born in Torzhok, a town in the Tver Governorate of the Russian Empire, Alexei Georgievich Jawlensky initially seemed destined for a different path. Following family tradition, he pursued a military career, eventually becoming a staff captain. However, a burgeoning passion for art, ignited during visits to Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery, steered him towards a new destiny. While stationed in Moscow and later St. Petersburg, he began dedicating his free time to painting and artistic study.

His formal artistic education commenced at the prestigious St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. There, he studied under the influential Russian realist painter Ilya Repin, a master known for his powerful historical scenes and portraits. It was through Repin's circle that Jawlensky met Marianne von Werefkin, a wealthy and accomplished artist in her own right, who hailed from a noble Russian family. Werefkin recognized Jawlensky's potential and, putting aside her own painting career for nearly a decade, became his mentor, supporter, and companion.

This relationship proved crucial. Werefkin's encouragement and financial support allowed Jawlensky to immerse himself more fully in art. Together, they formed a dynamic partnership, sharing intellectual and artistic interests. Their decision to leave Russia marked a turning point, setting the stage for Jawlensky's integration into the burgeoning modernist movements of Western Europe.

Munich: A Crucible of Modernism

In 1896, Jawlensky, accompanied by Marianne von Werefkin and her protégée Helene Nesnakomoff (who would later become Jawlensky's wife), moved to Munich. The Bavarian capital was then a major European art centre, attracting artists from across the continent. It was here that Jawlensky's artistic identity truly began to form, nurtured by the city's progressive atmosphere and his interactions with fellow artists.

He enrolled briefly at Anton Ažbe's private art school, a popular destination for many Eastern European artists. Perhaps most significantly, he formed a deep and lasting friendship with Wassily Kandinsky, another Russian expatriate who would become a pioneer of abstract art. This friendship was central to Jawlensky's development and his involvement in the Munich avant-garde.

Together with Kandinsky, Werefkin, Gabriele Münter, Adolf Erbslöh, Alexander Kanoldt, and others, Jawlensky co-founded the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKV, or New Artists' Association of Munich) in 1909. The NKV aimed to organize exhibitions that showcased a diversity of modern art styles, moving beyond the confines of the established Secession movements. Jawlensky served as the association's vice-chairman for a time.

Internal disagreements about the direction of art, particularly concerning the increasing abstraction in Kandinsky's work, led to a split within the NKV in 1911. Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, and Alfred Kubin left to form the editorial team for Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) almanac. While Jawlensky did not formally leave the NKV immediately, he exhibited with the Blue Rider group in their seminal exhibitions in 1911 and 1912. He shared their spiritual aspirations for art and their interest in expressive colour and form, placing him firmly within this influential circle, which also included artists like August Macke.

Forging a Unique Vision: Colour, Form, and Emotion

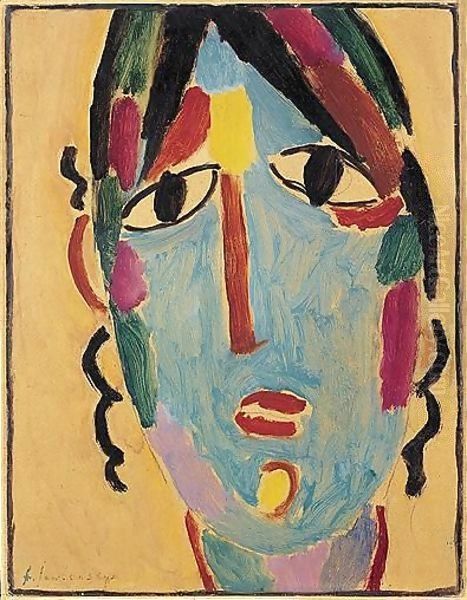

Jawlensky's time in Munich, punctuated by travels to France, was critical for the development of his signature style. He absorbed the lessons of French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, profoundly influenced by the bold colours and simplified forms of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and especially Henri Matisse. He met Matisse during a stay in Paris and was deeply impressed by the Fauves' liberation of colour from purely descriptive purposes.

His work from this period demonstrates a move away from his earlier, more realistic style influenced by Repin. He began using colour with increasing intensity and non-naturalism, applying paint often in broad, vigorous strokes. His subjects included landscapes, still lifes, and, increasingly, portraits. Works like Still Life with Jug and Apples (1908) show his engagement with Post-Impressionist structure, while landscapes such as Mediterranean at Marseilles (1905) reveal his burgeoning interest in vibrant colour harmonies learned from the Fauves.

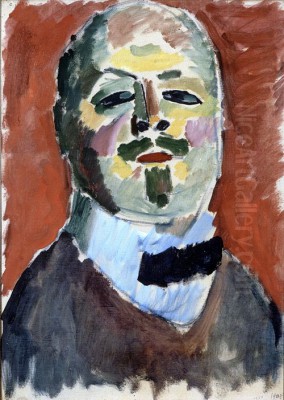

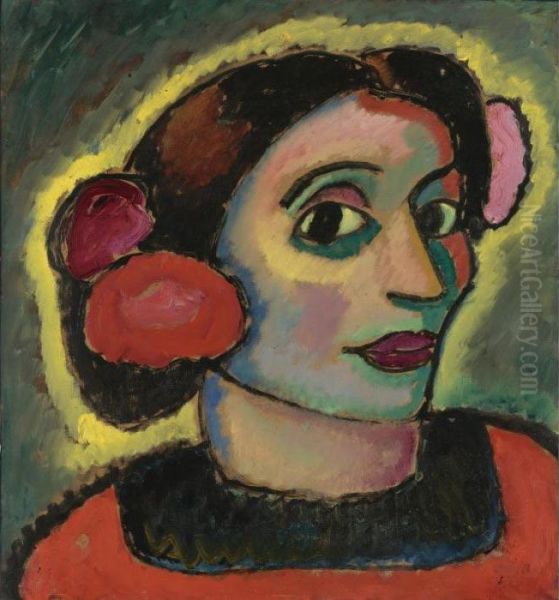

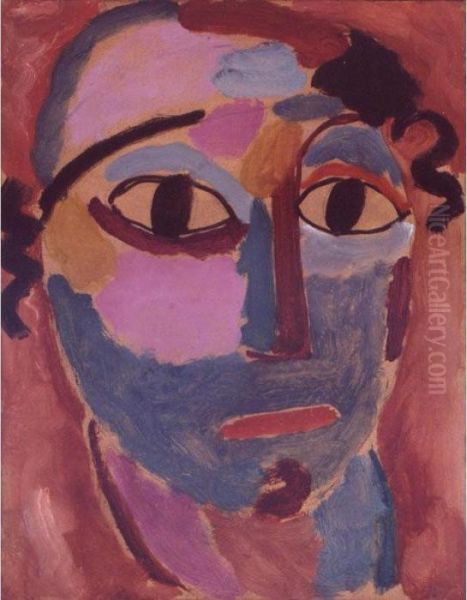

However, it was in portraiture that Jawlensky found his most enduring theme. He sought to capture not just the physical likeness of his sitters but their inner essence, their spiritual core. He simplified forms, often outlining them with dark, heavy contours reminiscent of stained glass or Russian icons – another significant influence on his work. The faces he painted became vehicles for intense emotional and spiritual expression, rendered in palettes that ranged from fiery reds and yellows to deep blues and greens. His Spanish Woman (Spanierin) and Woman in a Red Blouse (1911) are powerful examples from this formative period, showcasing his mastery of expressive colour and form.

The Iconic Heads: Variations on a Human Theme

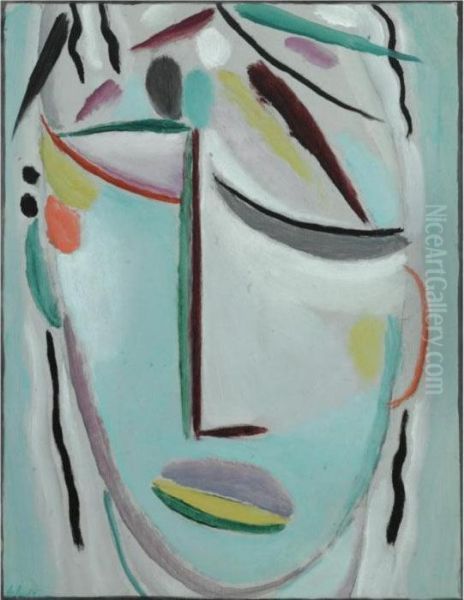

Over time, Jawlensky's focus narrowed almost exclusively to the human head. This subject became an obsessive motif, a framework through which he could explore variations in colour, form, and, most importantly, spiritual feeling. He worked in series, allowing him to delve deeply into the expressive possibilities of this single theme. These series represent the core of his artistic output and his most significant contribution to modern art.

His approach evolved systematically. Initially, the heads retained a degree of individual likeness, though highly stylized and emotionally charged, as seen in works like Astonishment (1919). Following his move to Switzerland during World War I, his work took a more introspective and abstract turn. He began the Mystical Heads (Mystische Köpfe) and later the Saviour's Faces (Heilandsgesichte) series, where features became more schematic, reduced to essential lines and planes of colour.

The culmination of this process came in his Abstract Heads (Abstrakte Köpfe) and the final Meditations series, produced in the 1930s. In these late works, the human face is distilled into a near-abstract formula: a U-shape for the head, horizontal lines for eyes and nose, and a vertical line connecting them, often resembling a cross. Colour became darker, more subdued, yet intensely resonant. These small, icon-like paintings, such as Large Meditation: Before Night Falls (1936), are powerful expressions of contemplation, suffering, and spiritual seeking, reflecting Jawlensky's deep religiosity, rooted in his Russian Orthodox background. He described these works as a form of prayer.

Exile and Introspection: The Swiss Years

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 dramatically altered Jawlensky's life. As a Russian citizen, he was considered an enemy alien in Germany and was forced to leave. He sought refuge in Switzerland, settling in Saint-Prex on the shores of Lake Geneva. This period of exile, lasting until 1921, was one of relative isolation but also intense artistic productivity and introspection.

Separated from the dynamic art scene of Munich, Jawlensky turned his attention inward and to his immediate surroundings. He began a significant series known as the Variations on a Landscape Theme. Painting the view from his window overlooking the lake, trees, and path, he created hundreds of small, semi-abstract compositions. In these works, he explored subtle shifts in light, colour, and atmosphere, transforming the landscape into patterns of spiritual feeling. This serial approach, focusing intensely on a limited motif, paralleled his developing work on the human head and further honed his abstract language.

The Swiss years also marked a shift in his personal life. His long-standing relationship with Marianne von Werefkin, which had become strained, eventually ended in 1921. The following year, after returning to Germany, Jawlensky would marry Helene Nesnakomoff, who had been part of their household since their arrival in Munich and was the mother of his only son, Andreas, born in 1902.

The Blue Four: Transatlantic Connections

In 1921, Jawlensky moved back to Germany, settling in Wiesbaden. He reconnected with old friends and colleagues and continued to develop his art. A significant development during this period was the formation of Die Blauen Vier (The Blue Four) in 1924. This group brought Jawlensky together with three other major figures of modern art: Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger.

The idea for The Blue Four came from Galka Scheyer, a German-American art dealer, collector, and artist herself. She proposed forming an alliance to promote their work, particularly in the United States. Scheyer became their dedicated agent, organizing exhibitions, lectures, and sales across America throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The name "Blue Four" deliberately echoed the earlier "Blue Rider," signalling a continuity of artistic spirit, emphasizing the spiritual and lyrical qualities in their diverse, yet related, abstract and semi-abstract styles.

While the four artists worked independently, their association under Scheyer's guidance helped establish their reputations internationally, especially in the US, where modern European art was gaining increasing attention. For Jawlensky, this provided crucial exposure during a time when the economic and political climate in Germany was becoming increasingly challenging.

Confronting Adversity: Later Life and Legacy

The final phase of Jawlensky's life was marked by both artistic culmination and profound personal hardship. He continued to refine his Abstract Heads and Meditations series, achieving a remarkable depth of spiritual expression in these highly concentrated works. However, from 1929 onwards, he began suffering from severe, crippling arthritis.

This debilitating condition progressively limited his physical ability to paint. By the mid-1930s, the pain was so intense that he often had to work using both hands to guide the brush. Despite this immense struggle, he persevered, producing some of his most moving works during this period. His determination to continue creating art in the face of physical agony speaks volumes about his dedication and the spiritual necessity he felt in his work.

Compounding his physical suffering was the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany. Like many modern artists, Jawlensky's work was deemed unacceptable by the authorities. In 1937, his art was officially declared "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst). Seventy-two of his works were confiscated from German museums, and he was forbidden from exhibiting. This persecution effectively silenced him publicly in Germany and added emotional distress to his physical pain.

By 1938, the arthritis had become so severe that Jawlensky was forced to stop painting altogether. He spent his last few years confined to his home in Wiesbaden, cared for by Helene and Andreas. Alexei von Jawlensky died on March 15, 1941, leaving behind a legacy forged in colour, spirit, and resilience.

Jawlensky in the Art Market: Recognition and Value

Posthumously, Jawlensky's reputation has steadily grown, and he is now recognized as a major figure in German Expressionism and 20th-century modern art. His works are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Museum Wiesbaden, which houses a significant collection, the Lenbachhaus in Munich, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and many others.

His paintings command high prices on the international art market, reflecting his established importance. Auction records demonstrate the strong demand for his work. For instance, his painting Schokko mit weit geöffneten Augen (often translated as Schokko With Wide-Brimmed Hat or similar, referring to a favourite model) sold for $8.3 million in 2003 and then achieved a remarkable $18.6 million in 2008. More recently, in June 2024, one of his oil paintings reportedly set a new personal auction record at €8.338 million. Works like Grand Meditation: "Herr! Lass mich erglühen" (Lord! Let me glow) continue to appear at auction with significant estimates, indicating sustained collector interest. Even smaller works on paper or later, more abstract pieces like Mysterious Head - Blue Mouth fetch considerable sums. This market success underscores the art historical significance and enduring visual power attributed to his oeuvre.

Enduring Influence: Jawlensky's Place in Art History

Alexei von Jawlensky's art occupies a unique space, bridging the spiritual traditions of Russian icon painting with the formal innovations of Western European modernism. His intense engagement with colour, learned partly from Matisse and the Fauves, was fused with the emotional intensity characteristic of German Expressionism, as practiced by his colleagues in the Blue Rider like Kandinsky, Marc, and Macke. His serial approach to themes, particularly the human head, anticipates later developments in conceptual and minimalist art, while the profound spirituality of his late work offers a counterpoint to the more secular trends in modernism.

He remains celebrated for his ability to convey deep emotion and spiritual resonance through simplified forms and powerful colour relationships. His journey from representational painting to near abstraction, focused through the lens of the human face, provides a compelling narrative of artistic exploration and inner searching. Alongside contemporaries like Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger, and Münter, Jawlensky helped shape the course of Expressionism and abstract art, leaving an indelible mark on the history of modern painting. His work continues to inspire and move audiences with its vibrant colour, formal strength, and profound humanity.