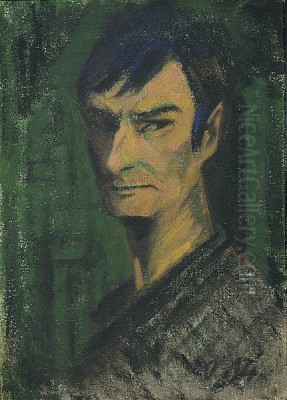

Otto Mueller stands as a distinctive figure within the vibrant landscape of German Expressionism. A painter and printmaker associated with the influential artist group Die Brücke (The Bridge), Mueller carved a unique path characterized by a lyrical sensibility, a harmonious integration of the human figure with nature, and a fascination with Romani life. Born on October 16, 1874, in Liebau, Silesia (now Lubawka, Poland), and passing away on September 24, 1930, in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), Mueller's life and art navigated the turbulent currents of early 20th-century Europe, leaving behind a legacy of serene yet emotionally resonant works. His approach, often softer and more decorative than that of his Brücke colleagues, focused on an idealized vision of humanity in tune with the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Otto Mueller's origins provided a unique backdrop to his artistic development. His father was a tax official and former military lieutenant, while his mother possessed Romani heritage, a background that would profoundly influence his later artistic themes and perhaps his sense of identity, often being referred to, sometimes affectionately, sometimes perhaps isolatingly, as "The Gypsy" Mueller. He spent his formative years in Görlitz and Liebau in Silesia. His initial artistic training was practical rather than academic; from 1890 to 1894, he undertook an apprenticeship in lithography in Görlitz and Breslau. This grounding in printmaking techniques would remain fundamental throughout his career.

Following his apprenticeship, Mueller sought formal art education at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste Dresden) from 1894 to 1896. However, he found the institution's conservative atmosphere stifling and left without completing his studies. His independent spirit led him to Munich in 1898, hoping to study under the renowned Symbolist painter Franz von Stuck at the Munich Academy. Unfortunately, Stuck did not accept him as a student, marking another turn towards self-reliance in Mueller's artistic journey.

Despite these academic setbacks, Mueller was undeterred. He engaged deeply with the art world around him, absorbing influences from various contemporary movements. Early works show an engagement with Impressionism, Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), and Symbolism. Artists like Arnold Böcklin, with his mythological landscapes, likely resonated with Mueller's developing interest in atmospheric scenes. He spent time traveling, including a trip to Switzerland and Italy with his cousin, the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, further broadening his horizons. He also formed crucial relationships, meeting his future wife, Maria "Maschka" Mayhoffer, around 1900-1901. Maschka became his most important model and a constant presence in his life and art, even through subsequent marriages and divorces.

Berlin and Die Brücke

The year 1908 marked a pivotal moment when Mueller moved to Berlin. The city was a burgeoning center of artistic innovation and avant-garde activity. It was here that Mueller's path converged with the artists of Die Brücke. Founded in Dresden in 1905 by architecture students Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel, the group aimed to forge a "bridge" between traditional German art and a modern, expressive future. They sought raw emotional intensity, vibrant color, and simplified forms, drawing inspiration from German Gothic art, African and Oceanic sculpture, and Post-Impressionist painters like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.

Mueller formally joined Die Brücke in 1910, becoming its last major member alongside Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein who had joined earlier. Although slightly older and arriving with a more developed, albeit less aggressively radical style, Mueller found common ground with the group's emphasis on direct expression, communal living and working (especially during summer excursions to places like the Moritzburg Lakes near Dresden), and a shared interest in depicting the nude figure in natural settings as a symbol of primal freedom.

Within Die Brücke, Mueller maintained his distinct artistic personality. While Kirchner, Heckel, and Schmidt-Rottluff often employed jagged lines, dissonant colors, and a sense of urban anxiety or psychological tension, Mueller's work retained a greater sense of harmony, lyricism, and decorative flatness. His figures, though simplified and elongated, often possess a gentle, melancholic grace. His color palette, while expressive, tended towards more muted, earthy tones – ochres, greens, blues, and blacks – compared to the often strident hues of his colleagues. This difference led to his style sometimes being described as a more "lyrical" or "decorative" form of Expressionism. He shared subjects with the group, particularly bathers in landscapes, but his treatment emphasized tranquility and integration rather than tension.

The Die Brücke collective dissolved in 1913, largely due to internal disagreements, particularly concerning Kirchner's somewhat self-aggrandizing account of the group's history in the Chronik der Brücke. Despite the group's relatively short existence, its impact on German art was profound, and Mueller's association with it solidified his place within the Expressionist movement. He remained friends with several members, particularly Heckel.

Signature Style and Technique

Otto Mueller's mature style is instantly recognizable for its unique blend of Expressionist simplification and a distinct, almost archaic elegance. A key element was his technical approach. He developed a highly personal method of painting using distemper (Leimfarbe), a type of paint where pigments are bound with glue size, often applied to coarse canvas or burlap (Nessel). This technique resulted in a dry, matte, fresco-like surface, devoid of the glossy sheen of oil paint. The rough texture of the support often remained visible, contributing to the tactile quality and earthy feel of his works.

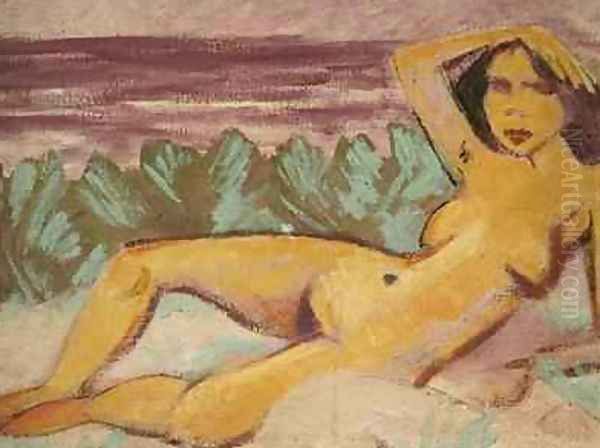

His handling of form was characterized by simplification and stylization. Figures are often elongated, with angular contours yet possessing a certain fluidity. There is a clear influence from ancient Egyptian art, particularly visible in the profile or semi-profile views of heads, the frontal depiction of eyes, and the linear emphasis. This connection to archaic forms aligns with the broader Expressionist interest in "primitive" art as a source of directness and authenticity, also seen in the works of Paul Gauguin, whose Tahitian scenes find an echo in Mueller's idealized bathers. The structural influence of Paul Cézanne can also be discerned in the way Mueller constructed his compositions.

Color in Mueller's work serves both descriptive and emotional purposes, but rarely with the jarring intensity of Nolde or Kirchner. He favored a limited palette dominated by ochre yellows, muted greens, soft blues, earthy browns, and strong black outlines. These colors contribute to the overall harmony and decorative quality of his compositions, creating a sense of unity between figures and their surroundings. The matte finish of the distemper further subdued the colors, enhancing the feeling of calm and timelessness.

The integration of figure and landscape is perhaps the most defining characteristic of Mueller's art. His nudes are rarely presented in isolation; they inhabit forests, stand by lakeshores, or recline among reeds. Nature is not merely a backdrop but an essential part of the figures' existence, a space of refuge and belonging. This harmonious relationship reflects an Arcadian ideal, a longing for a simpler, more natural state of being, away from the complexities and alienation of modern industrial society.

Major Themes

Throughout his career, Otto Mueller consistently explored a few central themes, each reflecting his core artistic and personal preoccupations.

The Nude in Nature

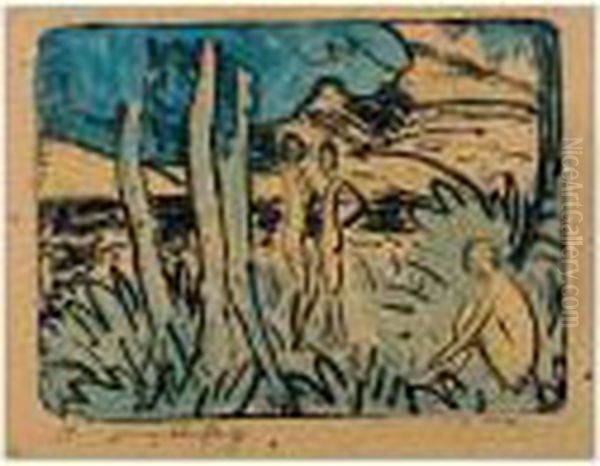

The depiction of nude figures, particularly female nudes, in natural settings is arguably Mueller's most recurrent theme. These works often portray bathers by lakes or streams, figures resting in forests, or couples intertwined in landscapes. These scenes are not typically erotic in an overt sense; rather, they evoke a sense of peaceful coexistence with nature, an idyll of unselfconscious freedom. Works like Zwei Mädchen im Schilf (Two Girls in the Reeds) or his numerous Badende (Bathers) compositions exemplify this theme. The figures seem almost to merge with their surroundings, their simplified forms echoing the shapes of trees, water, and earth. This theme connects strongly to the Die Brücke artists' shared practice of working outdoors and depicting nude models at the Moritzburg Lakes, seeking a return to a more primal state.

Romani Life

Mueller's fascination with Romani culture, often referred to in the context of his time as "Gypsy" life, is another defining aspect of his oeuvre. Stemming perhaps from his own maternal heritage and certainly from an attraction to what he perceived as a free, nomadic lifestyle close to nature, Mueller frequently depicted Romani families, mothers and children, and solitary figures. Works such as Zigeunermadonna (Gypsy Madonna) or Zigeunerfamilie (Gypsy Family) portray these subjects with dignity and a sense of quiet intimacy. While reflecting a Romanticized view of Romani life common among artists seeking alternatives to bourgeois society, these works stand out for their empathetic portrayal. It is important, however, to view these depictions through a contemporary lens, acknowledging the complexities of representation and potential stereotyping, even as we recognize Mueller's personal connection and artistic intent.

Landscapes

While figures usually dominate his compositions, Mueller also produced pure landscapes. These works further demonstrate his deep connection to the natural world, often depicting the forests, lakes, and dunes of Germany and Eastern Europe. Even without figures, his landscapes convey a similar mood of tranquility and harmony, rendered in his characteristic muted palette and simplified forms. They often serve as studies in atmosphere and light, captured through his unique distemper technique.

Printmaking

Otto Mueller was a master printmaker, and his work in lithography and woodcut constitutes a significant part of his artistic output. His early training in lithography provided a strong foundation, and he continued to explore its possibilities throughout his life. His lithographs, often colored, possess the same stylistic features as his paintings: simplified forms, strong outlines, and a focus on harmony. Works like the color lithograph Fünf gelbe Akte am Wasser (Five Yellow Nudes by the Water, 1921) showcase his ability to translate his vision into the print medium effectively.

He also created powerful woodcuts, embracing the expressive potential of the medium favored by his Die Brücke colleagues. His woodcuts often feature stark contrasts and bold lines, yet retain his characteristic sense of rhythm and balance. Printmaking allowed Mueller to experiment with variations on his favorite themes, such as the Hockende (Crouching Woman) motif, and to make his work more widely accessible. His graphic work is considered integral to understanding his artistic achievement, complementing and sometimes informing his paintings.

War, Professorship, and Later Years

The outbreak of World War I interrupted Mueller's artistic career. He served as a soldier from 1916 to 1917 but was discharged after suffering a severe lung infection, an ailment that would plague him for the rest of his life. The war experience, though brief, likely deepened his longing for peace and harmony, reinforcing the escapist, idyllic qualities already present in his art.

After the war, in 1919, Mueller achieved significant academic recognition when he was appointed a professor at the prestigious State Academy of Arts and Crafts in Breslau (Staatliche Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe Breslau). He held this position until his death in 1930. The Breslau years were productive; he continued to refine his signature style and themes, influencing a generation of students. He traveled during this period, including trips to Dalmatia, Hungary, and Romania, seeking out Romani communities and landscapes that inspired his work. Despite ongoing health problems related to his lungs, he remained dedicated to his art and teaching. His personal life continued to have its complexities; he divorced Maschka and later married Elsbeth Lübke, followed by another divorce and marriage to Elfriede Timm.

"Degenerate Art" and Posthumous Reception

Otto Mueller died relatively young, at the age of 55, in 1930, just before the Nazi regime came to power in Germany. He was thus spared witnessing the direct persecution that many of his avant-garde contemporaries endured. However, his art was posthumously targeted by the Nazis. In the infamous "Degenerate Art" (Entartete Kunst) campaign, which aimed to purge modern art from Germany, Mueller's work was deemed unacceptable. In 1937, an astonishing 357 of his works were confiscated from German museums. Some were sold abroad, while others were likely destroyed.

This official condemnation cast a shadow over Mueller's reputation during the Nazi era. However, after World War II, his importance within German Expressionism was gradually re-evaluated and reaffirmed. His works began to reappear in exhibitions, including the influential Documenta exhibitions in Kassel, which played a crucial role in rehabilitating modern art in Germany.

Today, Otto Mueller is recognized as a major figure of German Expressionism, albeit one with a unique voice. His work is held in high esteem and can be found in major museums worldwide, including the Brücke Museum in Berlin, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and numerous other public and private collections. Art historians appreciate his distinctive lyrical style, his technical innovations with distemper, and his consistent exploration of the harmony between humanity and nature. He offers a quieter, more contemplative counterpoint to the often-raw intensity of artists like Kirchner or Nolde, yet shares with them a profound engagement with the emotional and spiritual landscape of modernity. His work continues to resonate with viewers seeking beauty, tranquility, and a connection to the natural world. He stands alongside other key figures of the era, such as the Austrian Expressionists Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, or German artists like Max Beckmann, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Lovis Corinth, as a vital contributor to the diverse tapestry of early 20th-century European art.

Conclusion

Otto Mueller's artistic legacy is defined by its consistency of vision and its unique stylistic signature. As a member of Die Brücke, he participated in one of the foundational movements of German Expressionism, yet he always maintained a distinct artistic identity. His pursuit of harmony, his lyrical simplification of form, his innovative use of distemper on burlap, and his enduring focus on the nude in nature and Romani life set him apart. His art offers an escape into an idealized world where humanity exists in gentle accord with the natural environment, a vision rendered with quiet emotional depth and decorative elegance. Despite the challenges of his life and the posthumous persecution of his work, Otto Mueller's contribution to modern art remains significant, securing his place as a master of lyrical Expressionism and a poignant chronicler of the search for serenity in a tumultuous age.