Tadeusz Makowski stands as a significant yet uniquely individual figure in early 20th-century European art. A Polish painter who spent the most productive years of his career in Paris, Makowski navigated the turbulent currents of modernism, particularly Cubism, while forging a deeply personal style. His work is characterized by a profound engagement with the world of childhood, filtered through a lens that blended influences from Polish folk traditions, naïve art, and the sophisticated formal experiments of the Parisian avant-garde. His legacy rests on his ability to synthesize these diverse sources into a cohesive, often melancholic, and visually captivating artistic language.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Poland

Tadeusz Makowski was born on January 29, 1882, in Oświęcim, a town in southern Poland that was then part of Austria-Hungary. His father worked as a railway official, and the family environment seemingly recognized and nurtured his burgeoning artistic talents from a young age. Recognizing the need for formal training, his parents facilitated his move to Kraków, a major cultural and intellectual center in Poland, to pursue higher education and artistic studies.

His academic journey initially included studies in classical philology and philosophy at the prestigious Jagiellonian University in Kraków between 1902 and 1906. However, his true calling lay in the visual arts. Concurrently or shortly thereafter, he enrolled at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki), the leading art institution in Poland. He studied painting there formally from approximately 1902/1903 until 1908.

During his time at the Academy, Makowski studied under influential Polish artists who shaped the national art scene. His teachers included Jan Stanisławski, a renowned landscape painter associated with Polish Symbolism and Modernism, known for his atmospheric depictions of the Polish countryside. He also studied with Józef Mehoffer, a prominent figure of the Young Poland movement, celebrated for his work in painting, stained glass, and graphic arts, often characterized by rich ornamentation and symbolic depth. This education provided Makowski with a solid grounding in academic technique while exposing him to the prevailing currents of Polish modern art.

The Allure of Paris: A New Artistic Horizon

Upon completing his studies in Kraków around 1908, Makowski made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. This was a common trajectory for ambitious artists from across Europe and beyond during this era. Paris was undeniably the epicenter of the art world, a crucible of innovation where new movements were born and debated, and where artists could engage directly with the most radical ideas and influential figures of the time. For Makowski, the move represented an opportunity to broaden his artistic horizons and immerse himself in the international avant-garde.

He arrived in Paris and quickly began to integrate into the vibrant artistic community, particularly in Montparnasse, which was supplanting Montmartre as the favored haunt of painters, sculptors, writers, and intellectuals. This environment was crucial for his development. It was here that he would encounter the movements, particularly Cubism, that would profoundly impact his work, and forge connections with artists who would become friends, collaborators, and sources of inspiration. He would remain based in Paris for the rest of his life, a period spanning nearly twenty-five years until his death in 1932.

Encountering Cubism: Influence and Adaptation

Soon after arriving in Paris, Makowski came into contact with Cubism, the revolutionary art movement pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque that was challenging traditional notions of representation. Makowski did not become a doctrinaire Cubist, but the movement's principles of geometric simplification, fragmented forms, and multiple viewpoints left a discernible mark on his work, particularly in the years leading up to World War I.

He became acquainted with several key figures associated with the Cubist movement. A significant early influence was Henri Le Fauconnier, a painter whose style bridged Post-Impressionism and Cubism and who was known for his structured compositions and somewhat somber palette. Makowski absorbed Le Fauconnier's approach to form and structure. He also moved in circles that included other prominent Cubists such as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, who co-authored the influential treatise Du "Cubisme" (1912), as well as Fernand Léger, known for his distinctive "Tubist" style.

Makowski's engagement with Cubism was also intellectual. He formed friendships with important writers and poets associated with the avant-garde, most notably Guillaume Apollinaire, the influential critic and poet who championed Cubism and other modern movements. He also knew Pierre Reverdy, another poet closely linked to Cubism and later Surrealism. These interactions placed Makowski firmly within the dynamic discourse surrounding modern art in Paris. However, rather than simply adopting Cubist formulas, Makowski selectively integrated its structural lessons into his evolving personal vision.

Forging a Personal Style: Beyond Cubism

While Cubism provided Makowski with essential tools for formal experimentation, his artistic temperament led him away from its purely analytical or synthetic phases towards a more personal and emotionally resonant style. By the end of World War I and increasingly through the 1920s, he developed a unique visual language that synthesized his Parisian experiences with deeper-rooted influences.

A key element in this evolution was his reconnection with Polish folk art. The stylized forms, bold outlines, decorative patterns, and often earthy color palettes found in traditional Polish crafts and folk paintings resonated with Makowski's search for a more direct and expressive mode of representation. This influence is visible in the simplification of his figures, their sometimes rigid or puppet-like postures, and a certain decorative quality in his compositions.

He also drew inspiration from naïve or "primitive" art, which was highly valued by many modern artists (including Picasso and the German Expressionists) for its perceived authenticity, emotional directness, and freedom from academic conventions. Makowski's figures, particularly his depictions of children, often possess a wide-eyed innocence or a stark simplicity reminiscent of naïve art, though rendered with sophisticated technique. His work shares an affinity with artists like Henri Rousseau in its pursuit of a poetic, non-naturalistic reality.

Furthermore, elements of Expressionism can be discerned in his work, particularly in his use of color and line to convey mood and emotion rather than objective reality. The often somber palettes, dominated by browns, ochres, and grays, punctuated by occasional bursts of red or gold, contribute significantly to the evocative atmosphere of his paintings. His style became less about deconstructing objects and more about constructing a self-contained, poetic world.

The World of Childhood: A Central Theme

The most distinctive and recurring theme in Tadeusz Makowski's mature work is the world of children. He returned to this subject again and again, exploring it with a depth and consistency that sets him apart. His depictions of children are far removed from sentimental Victorian portrayals; instead, they possess a unique blend of innocence, melancholy, and sometimes unsettling mystery.

Makowski often portrayed children in groups, engaged in play, performing in makeshift theatres, or simply confronting the viewer with their solemn gazes. His figures are typically stylized, with simplified, almost geometric bodies and large heads, often resembling puppets, marionettes, or wooden folk toys. This stylization distances them from realistic portraiture, transforming them into archetypal figures inhabiting a world of Makowski's own creation.

Several of his representative works focus on this theme. Titles like Children's Paradise (Dziecięce eldorado), Children's Theatre (Teatrzyk dziecięcy), and Masks in the Dark (Maski w mroku) point to this preoccupation. The recurring motif of masks is particularly intriguing. Sometimes the children wear actual masks, referencing carnival or theatrical traditions, but often their faces themselves seem mask-like, suggesting hidden emotions, a sense of alienation, or the performative nature of social interaction, even among the young.

There is a strong element of Romanticism in his approach, emphasizing emotion, imagination, and the inner life. However, this is often tinged with a sense of unease or anxiety. The children in his paintings can appear isolated even when grouped, inhabiting dimly lit spaces or stark landscapes. This ambiguity invites psychological interpretation, suggesting themes of lost innocence, the anxieties of growing up, or a commentary on the human condition viewed through the lens of childhood.

Artistic Techniques and Characteristics

Makowski developed a highly recognizable technical approach. His compositions are carefully constructed, often retaining a subtle geometric underpinning derived from his Cubist phase, but softened and integrated into a more lyrical overall structure. He favored simplified, clearly defined forms, often outlined with dark contours, which contributes to the graphic quality of his work and recalls both folk art and woodcut techniques.

His use of color is distinctive. While capable of using brighter hues, his mature palette often revolves around a sophisticated range of earth tones: browns, ochres, grays, and muted greens. These are frequently enlivened by strategic accents of warmer colors like red or gold, which can highlight focal points or add emotional intensity. He masterfully manipulated light and shadow, often employing chiaroscuro effects to create a sense of volume, depth, and atmosphere, lending his scenes a theatrical or dreamlike quality.

The figures themselves, especially the children, are rendered in his characteristic stylized manner – somewhat stocky, with large heads and simplified features, often appearing doll-like or puppet-like. This deliberate departure from naturalism enhances the symbolic and emotional resonance of his work.

Beyond painting, Makowski was also skilled in graphic arts. He created woodcut illustrations for books, notably the Pastoralki series. These woodcuts share a strong visual kinship with his paintings, featuring similar stylized figures, bold outlines, and a focus on expressive simplicity. This demonstrates a consistency of vision across different media.

Other Subjects and Notable Works

While children were his dominant subject, Makowski also engaged with other genres. He painted landscapes, often imbued with the same melancholic or poetic atmosphere found in his figurative works. These landscapes sometimes feature simplified architectural elements or stylized natural forms, reflecting his consistent approach to composition and mood. Still life paintings also appear in his oeuvre, allowing for focused studies of form, color, and light on a smaller scale.

One notable work often cited is Węglarz (The Charcoal Burner). This painting exemplifies his mature style, depicting a solitary, rugged figure rendered with characteristic simplification and earthy tones. Interestingly, the authenticity of this particular work was once questioned, a common issue with artists of significant stature. However, its legitimacy was later confirmed by expert analysis, specifically by Adam Konopacki Art Consulting, highlighting the complexities that can surround an artist's oeuvre and market.

Life in Paris: Connections, Identity, and Personality

Makowski spent over two decades living and working in Paris, fully immersing himself in its artistic life. He was part of the vibrant, international community of artists often referred to as the School of Paris. He frequented the cafes and studios of Montparnasse and was known among the Parisian "Bohemians." His circle included not only the Cubist figures mentioned earlier but likely encompassed a wide range of artists and writers active during that fertile period. Other Polish artists were also active in Paris at the time, such as Moïse Kisling and Louis Marcoussis, contributing to a significant Polish presence within the School of Paris, alongside earlier figures like Władysław Ślewiński and Olga Boznańska.

Despite his deep integration into the French art scene and his long residency abroad, Makowski maintained a strong connection to his Polish identity. Sources suggest he remained keenly interested in news from Poland and identified primarily as a Polish artist working in Paris. This duality – embracing international modernism while retaining a distinct national sensibility, often expressed through folk art influences – is central to understanding his artistic position.

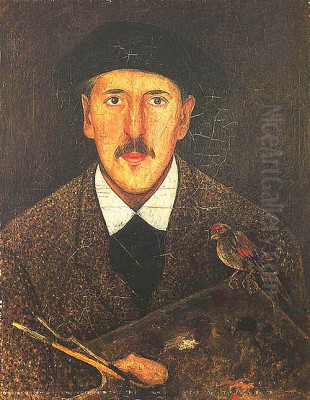

Descriptions of his personality paint a picture of a distinctive individual. He was reportedly tall and thin, often seen wearing a beret and smoking. His movements were described as slow but deliberate and focused. Contemporaries noted his charm, attributed partly to his artistic talent and his "Slavic" origins, combined with a sense of resilience and an ability to endure hardship without succumbing to bitterness.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Tadeusz Makowski's productive career was cut relatively short. He died in Paris on November 1, 1932, at the age of 50. His death prompted his friends and admirers to ensure his artistic contributions were recognized and preserved. Shortly after his passing, they formed the "Association of Friends of Tadeusz Makowski" (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Tadeusza Makowskiego).

This association played a crucial role in promoting his work posthumously. They organized major retrospective exhibitions of his art, notably in 1933 and 1936. These exhibitions were reportedly very successful, helping to solidify his reputation and introduce his unique vision to a wider audience both in France and internationally. His work began to be acquired by major museums, particularly the National Museums in Warsaw and Kraków, which now hold significant collections of his paintings and graphic works.

Today, Tadeusz Makowski is regarded as one of the most original Polish painters of the early 20th century. He holds an important place within the narrative of the School of Paris, representing a distinct voice that blended international modernist trends with personal and national sources. His unique focus on the theme of childhood, rendered with his characteristic blend of stylization, melancholy, and psychological depth, continues to fascinate viewers and art historians.

Critical Perspectives and Interpretations

Makowski's work, while admired for its originality and poetic quality, has also prompted various critical interpretations and discussions. The distinctive mood of his paintings – often described as melancholic, anxious, or even evoking a sense of fear – invites analysis. Critics have explored the psychological dimensions of his child figures, interpreting the masks and puppet-like qualities as symbols of alienation, social conformity, or the hidden complexities of the inner life.

The question of authenticity, as highlighted by the case of Węglarz, underscores the importance of provenance and expert verification in the art world, particularly for artists whose works command significant value and historical interest.

More recently, as with many artists of his era, his work has been viewed through contemporary critical lenses. Some scholars have raised questions about potential instances of racial stereotyping or sexualization in his depictions of non-European figures, such as Black women, reflecting broader issues within European art of the period regarding the representation of the "Other." Such discussions contribute to a more nuanced understanding of his work within its historical and cultural context.

Conclusion: A Unique Voice in Modern Art

Tadeusz Makowski carved a unique path through the complex landscape of early 20th-century art. A Polish artist deeply immersed in the Parisian avant-garde, he absorbed the lessons of Cubism but ultimately transcended its formulas to create a deeply personal and evocative style. By weaving together threads of modernism, Polish folk art, naïve simplicity, and a romantic sensibility, he developed a distinctive visual language.

His profound and often unsettling exploration of the world of childhood remains his most defining contribution. Through his stylized figures, carefully controlled palettes, and masterful handling of light and mood, Makowski created a self-contained artistic universe that speaks to universal themes of innocence, anxiety, community, and isolation. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of individual vision within the broader currents of art history, a bridge between the artistic soul of Poland and the modernist innovations of Paris. His work continues to resonate, inviting contemplation and offering a unique window onto the human condition.