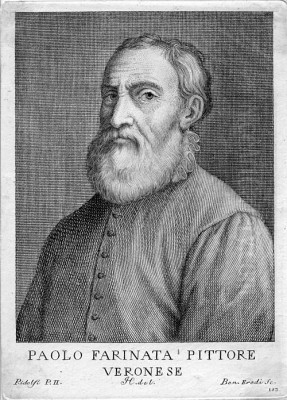

Paolo Farinati (1524–1606) stands as a prominent figure in the rich artistic tapestry of the Italian Renaissance, particularly within the vibrant cultural milieu of Verona. A versatile artist, Farinati excelled as a painter, etcher, and draughtsman, and also ventured into architecture and sculpture, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of his era. His long and prolific career, spanning much of the 16th century and into the early 17th, saw him become one of the most respected and sought-after artists in Verona and its surrounding territories. His work, characterized by a dynamic synthesis of Mannerist elegance and Venetian colorism, contributed significantly to the distinctive character of the Veronese school of painting.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in Verona in 1524, Paolo Farinati was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His father, Giovanni Battista Farinati, was a painter, and it is highly probable that Paolo received his initial artistic instruction within the family workshop. This early exposure to the craft would have provided him with a foundational understanding of materials, techniques, and the day-to-day operations of an artist's studio.

Following this initial tutelage, it is believed that Farinati continued his training in the workshop of Niccolò Giolfino, another established Veronese painter. Giolfino's studio was a significant training ground in Verona, and an apprenticeship there would have exposed Farinati to a broader range of stylistic currents and artistic practices prevalent in Northern Italy. During this formative period, the artistic scene in Verona was a melting pot of influences, absorbing trends from nearby Venice, Mantua, and even further afield from Central Italy.

The artistic climate of Northern Italy in the early to mid-16th century was particularly dynamic. The High Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo had already redefined the parameters of art, and their innovations were being disseminated and reinterpreted throughout the peninsula. In Venice, artists such as Titian and Tintoretto were pioneering a style characterized by rich color, dramatic lighting, and expressive brushwork. Simultaneously, the elegant, often elongated forms and complex compositions of Mannerism, championed by artists like Giulio Romano (who was highly active in nearby Mantua) and Parmigianino, were gaining traction. Farinati’s artistic development would be shaped by these diverse and powerful currents.

Artistic Development and Stylistic Hallmarks

Paolo Farinati’s style evolved throughout his long career, but it consistently displayed a sophisticated blend of influences. He was particularly receptive to the Mannerist tendencies that emphasized disegno (drawing or design) and a certain artificial grace. This can be seen in the elongated proportions of his figures, their elegant, often contorted poses, and the intricate compositions that characterize many of his works. Artists like Giulio Romano, whose dramatic and muscular figures adorned the Palazzo Te in Mantua, and Parmigianino, with his refined and serpentine forms, appear to have left a significant imprint on Farinati's approach to figure drawing and composition.

However, Farinati was also deeply connected to the Venetian tradition, which prioritized colore (color) and a more sensuous engagement with the painted surface. The influence of Venetian masters such as Titian and Giorgione is evident in his handling of color, particularly in his altarpieces and larger narrative scenes. While his palette could sometimes be more subdued, favoring earthy tones, greys, and rust reds, especially in his frescoes, he was also capable of deploying vibrant hues to achieve dramatic and emotive effects.

A key contemporary and friend who likely played a role in Farinati's artistic circle was Paolo Veronese (Paolo Caliari), another giant of the Veronese school who achieved international fame. Farinati was, in fact, the best man at Veronese's wedding. While their styles differed – Veronese being known for his opulent color and grand, festive scenes – their shared Veronese heritage and professional interactions undoubtedly fostered a rich artistic dialogue. Farinati’s work, though, often retained a more graphic quality and a certain austerity that distinguished it from Veronese's more luminous and decorative approach.

Michelangelo's powerful and anatomically complex figures also resonated with Farinati, as they did with many artists of his generation. This influence is discernible in the muscularity and dynamic energy of some of Farinati's figures, particularly in his large-scale fresco cycles. He skillfully integrated these diverse influences into a personal style that was both sophisticated and robust, capable of conveying complex narratives and profound religious sentiment.

Major Works and Ecclesiastical Commissions

Paolo Farinati was exceptionally prolific, undertaking numerous commissions for churches, palaces, and private patrons primarily in Verona and the Veneto region. His oeuvre includes a vast number of altarpieces, frescoes, and individual paintings, many of which still adorn their original locations or are housed in prestigious museum collections.

One of his early significant works is the altarpiece Saint Martin and the Beggar, painted in 1552 for the Duomo (Cathedral) of Mantua. This piece demonstrates his burgeoning skill in composing large-scale narrative scenes and his ability to convey emotional depth. The dynamic interaction between the figures and the careful rendering of textures showcase his early mastery.

In Verona, Farinati was a dominant artistic presence. He executed numerous works for the city's churches. Among his notable commissions is the Assumption of the Virgin (1556) for the church of Santa Maria in Organo. This work, with its upward-sweeping composition and expressive figures, reflects the artist's engagement with both Mannerist compositional devices and Venetian emotional intensity.

The church of San Giorgio in Braida in Verona became a significant site for Farinati's later works. Here, he painted the monumental Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes in 1603. This vast canvas, teeming with figures, demonstrates his enduring skill in managing complex compositions and his mature, confident style. The painting is a testament to his ability to orchestrate large groups of figures into a coherent and dramatic narrative, a hallmark of late Renaissance painting.

Other important ecclesiastical works include frescoes and altarpieces for the church of San Marco in Verona, such as an altarpiece of the Madonna and Child dated 1588, and frescoes in San Giovanni in Valle. He also created works like the Madonna and Child with Saints Nicholas and Francis (1561), showcasing his ability to create devotional images imbued with a quiet dignity. An earlier piece, Saints Barbara, Anthony Abbot, and Roch, further illustrates his contributions to Veronese altarpieces.

His involvement extended to architectural decoration, such as the frescoes he contributed to the Castello di San Pietro (often referred to as Castel San Pietro, though the reference to "San Castello" in Mantua in some sources might be a slight confusion or refer to a different, less prominent commission, as his primary base was Verona). His frescoes often depicted mythological or historical scenes, executed with a characteristic vigor and attention to narrative clarity.

The Veronese School and Farinati's Position

The Veronese school of painting, while part of the broader Venetian artistic sphere, developed its own distinct characteristics. Artists from Verona, including Farinati, Paolo Veronese, Domenico Brusasorci (Domenico Riccio), Battista del Moro, and Antonio Badile, contributed to a style that often combined the Venetian emphasis on color with a strong tradition of draughtsmanship and a particular local flavor.

Farinati was a central figure in this school. His style, with its blend of Mannerist elegance and Venetian chromatic richness, was influential. He maintained a busy workshop, which not only fulfilled numerous commissions but also trained a new generation of artists, ensuring the continuation of Veronese artistic traditions. His emphasis on strong drawing and dynamic composition became a hallmark that resonated with other local painters.

Compared to the more purely Venetian painters like Titian or Tintoretto, Veronese artists often displayed a greater interest in complex spatial arrangements and a certain decorative flair that was well-suited to large-scale fresco cycles in villas and palaces. Farinati's work, while sometimes more somber in tone than that of Veronese, shared this aptitude for monumental decoration. He was adept at creating expansive narrative scenes that could animate large wall surfaces, engaging the viewer with dramatic storytelling and skillfully rendered figures.

The Master Draughtsman and Printmaker

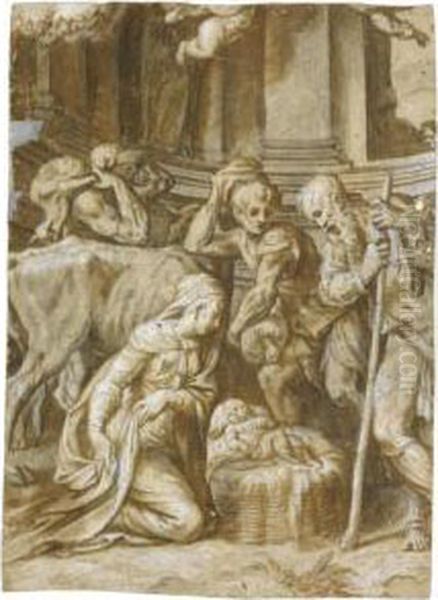

Paolo Farinati was an exceptionally gifted and prolific draughtsman. Around five hundred of his drawings are known to survive, a testament to his dedication to this medium. His drawings were not merely preparatory studies for paintings but were often highly finished works of art in their own right, sought after by collectors even during his lifetime.

He typically worked in pen and ink with brown wash, often heightened with white, on colored paper (frequently blue, a common practice in Venetian-influenced drawing). His drawing style is characterized by its energy, fluidity, and a distinctive, somewhat wiry line. He had a remarkable ability to capture movement and anatomical form with a few deft strokes. These drawings cover a wide range of subjects, including religious scenes, mythological episodes, allegories, and studies from life.

The art historian Carlo Ridolfi, writing in the 17th century, specifically praised Farinati's drawings for their quality and inventiveness. Many of these drawings were preserved in albums by collectors, indicating their esteemed status. Today, Farinati's drawings are found in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Albertina in Vienna.

Farinati also engaged in printmaking, producing etchings that helped to disseminate his compositions to a wider audience. His prints often mirrored the subjects and style of his drawings and paintings, characterized by a lively line and dramatic use of light and shadow. This aspect of his work further underscores his versatility and his engagement with the various artistic media available to Renaissance artists.

Architectural Interests and Decorative Schemes

While primarily known as a painter and draughtsman, Paolo Farinati also had interests in architecture. There is evidence that he provided designs for architectural projects and was involved in the decorative planning of entire spaces. His understanding of perspective and spatial composition, honed through his work as a painter of large-scale frescoes, would have naturally lent itself to architectural design.

His involvement in projects like the fresco decorations for palaces and villas often required a holistic approach, integrating painted narratives with the architectural framework. This often meant working closely with architects or even contributing to the design of architectural elements to create a unified decorative scheme. The 2005 exhibition in Verona, "Paolo Farinati 1524-1606: dipinti, incisioni e disegni per l'architettura," specifically highlighted his contributions and designs related to architecture, underscoring this less-explored facet of his career.

His ability to visualize and execute complex decorative programs that harmonized with their architectural settings was a key aspect of his success. This skill was highly valued by patrons who sought to transform their residences and chapels into impressive displays of art and status.

The Farinati Workshop and Artistic Legacy

Paolo Farinati managed a highly productive and successful workshop in Verona. This was a family enterprise, with his son Orazio Farinati (c. 1559 – after 1616) also becoming a painter and working closely with his father. Another son, Giambattista Farinati, is also mentioned as an artist. The workshop employed other assistants and collaborators to help manage the large volume of commissions Farinati received.

The existence of such a well-organized family workshop was somewhat unusual for the period, though not unheard of (the Bellini family in Venice is another example). It allowed Farinati to undertake ambitious, large-scale projects and maintain a consistent output over many decades. Orazio, in particular, seems to have absorbed his father's style and continued to work in a similar vein, helping to perpetuate the Farinati artistic legacy in Verona into the early 17th century.

Farinati's influence extended beyond his immediate family. His distinctive style and his prominence in the Veronese art scene would have impacted other local artists. His dedication to drawing and his ability to synthesize various artistic currents provided a model for younger painters. The sheer volume of his work in Verona's churches and public spaces ensured that his art remained visible and influential for generations.

Personal Life, Aspirations, and the Artist's Diary

Beyond his artistic endeavors, glimpses into Paolo Farinati's personal life reveal a man of ambition and meticulous habits. One interesting anecdote concerns his later-life aspiration to elevate his social standing. He reportedly attempted to associate himself with the noble Farinata degli Uberti family of Florence, even adopting their coat of arms. This desire for noble status was not uncommon among successful Renaissance artists, who often sought to transcend their artisan origins and gain greater social recognition. Figures like Titian, for example, achieved noble rank.

A particularly valuable resource for understanding Farinati's career and daily life is his Giornale (journal or daybook), which he maintained meticulously from 1573 until his death in 1606. This diary records his commissions, payments, patrons, and details about the progress of his works. It provides an invaluable window into the practicalities of being a successful artist in the late Renaissance, shedding light on his business practices, his network of patrons (which included local nobility, ecclesiastical bodies, and confraternities), and the economic aspects of his workshop. Such detailed records are relatively rare for artists of this period and make Farinati's career exceptionally well-documented.

The diary also hints at personal matters, including family disputes, which suggest that despite his professional success, his later years were not without their challenges. These personal touches humanize the artist and provide a richer understanding of the man behind the art.

Historical Reception and Scholarly Reassessment

Paolo Farinati enjoyed considerable acclaim during his lifetime. His ability to secure consistent and prestigious commissions over several decades attests to the high regard in which he was held by his contemporaries. His works were sought after, and his drawings, as noted, became collectors' items.

In the centuries following his death, his reputation, like that of many Renaissance artists, experienced fluctuations. While he was always recognized as a significant figure within the Veronese school, the broader art historical narratives sometimes overshadowed regional masters in favor of the giants of Florence, Rome, and Venice. However, art historians like Carlo Ridolfi in the 17th century helped to keep his memory alive, particularly praising his skill as a draughtsman.

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen a renewed scholarly interest in Paolo Farinati. Modern art historians have undertaken more in-depth studies of his oeuvre, analyzing his stylistic development, his influences, and his specific contributions to the art of Verona and the Veneto. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as the comprehensive 2005 show in Verona, have played a crucial role in bringing his art to a wider public and fostering deeper academic research.

These reassessments have highlighted the quality and diversity of his output, from monumental frescoes to intimate drawings. Scholars have explored his relationship with Mannerism and the Venetian school, his role in architectural decoration, and the operations of his workshop. The study of his Giornale has also provided rich material for social and economic historians of art.

Contemporary Understanding and Enduring Significance

Today, Paolo Farinati is recognized as one of the most important and prolific artists of the Veronese Renaissance. His ability to absorb and synthesize diverse artistic influences – from the linear grace of Mannerism to the chromatic richness of Venice, and the power of Michelangelo – resulted in a distinctive and influential personal style.

His contributions to the decoration of Verona's churches and palaces were immense, shaping the visual landscape of the city. His altarpieces and frescoes served as powerful expressions of religious devotion and civic pride. As a draughtsman, he stands out for the sheer volume, quality, and energy of his surviving drawings, which offer profound insights into his creative process.

The ongoing research into his life and work continues to illuminate his achievements. His works in major museum collections around the world ensure that his art remains accessible for study and appreciation. Farinati's legacy is that of a versatile, industrious, and highly skilled artist who played a pivotal role in the artistic culture of 16th-century Verona, leaving behind a rich body of work that continues to engage and inspire. He remains a key figure for understanding the complexities and regional variations of the Italian Renaissance.

Conclusion: A Master of Versatility and Expression

Paolo Farinati’s long and productive career marks him as a cornerstone of the Veronese school and a significant artist of the later Italian Renaissance. His mastery spanned painting, drawing, etching, and architectural design, demonstrating a versatility that was characteristic of the era's greatest talents. From the grand frescoes that adorned the walls of Verona's sacred and secular buildings to the dynamic energy of his numerous drawings, Farinati's art consistently reveals a sophisticated intellect and a profound understanding of form, composition, and narrative.

His ability to navigate and synthesize the dominant artistic currents of his time—Mannerist elegance, Venetian colorism, and the enduring influence of High Renaissance masters—allowed him to forge a distinctive and personal style. Through his prolific workshop and his influential position in Veronese artistic life, he not only created an extensive body of work but also contributed to the training of a new generation of artists. The meticulous record he kept in his Giornale further provides an unparalleled glimpse into the life and practice of a Renaissance artist. Paolo Farinati's enduring legacy lies in his rich artistic production, which continues to be studied and admired for its technical skill, expressive power, and its vital contribution to the cultural heritage of Verona and the broader Italian Renaissance.