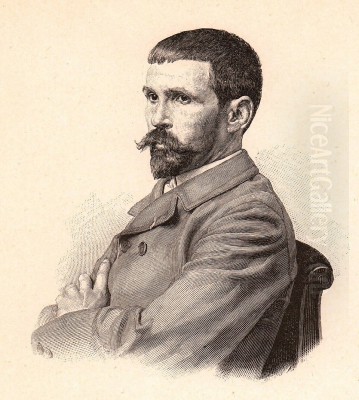

Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret stands as one of the foremost figures of French Naturalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His meticulously detailed canvases, often depicting scenes of peasant life, religious devotion, and poignant human moments, captured the spirit of his time while adhering to a rigorous academic technique. His ability to blend precise observation with deep emotional resonance earned him widespread acclaim and a lasting place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris on January 7, 1852, Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan had a somewhat unconventional upbringing. His father, a tailor, relocated to Brazil, leaving young Pascal in the care of his maternal grandfather, Gabriel Bouveret. In a gesture of affection and respect, the artist later appended his grandfather's surname to his own, becoming known as Dagnan-Bouveret. This early separation and the strong bond with his grandfather likely instilled in him a sense of resilience and a deep appreciation for familial connections, themes that would subtly permeate his later work.

Despite his father's wish for him to pursue a more conventional trade, Dagnan-Bouveret was resolutely drawn to art. In 1869, at the age of seventeen, he gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution was the bastion of academic art in France, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of classical and Renaissance masters. Here, he became a student of two of the era's most influential academic painters: Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Alexandre Cabanel, known for his elegant mythological and historical paintings such as The Birth of Venus (1863), would have imparted a strong foundation in classical composition and idealized form. Jean-Léon Gérôme, on the other hand, was celebrated for his highly detailed historical and Orientalist scenes, often characterized by a near-photographic realism and dramatic storytelling. Gérôme's meticulous approach to detail and his emphasis on accuracy profoundly influenced Dagnan-Bouveret's developing style. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 and the subsequent Paris Commune briefly interrupted his studies, but he resumed his artistic education with renewed determination in 1872.

Emergence at the Salon and Early Success

Dagnan-Bouveret made his debut at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, in 1875. His submission, Atalanta Victorious (1876), a mythological subject depicting the fleet-footed heroine, garnered positive attention and signaled the arrival of a promising new talent. This early work demonstrated his mastery of academic principles, including anatomical precision and dynamic composition, learned under Cabanel and Gérôme.

In these formative years, his subjects often drew from mythology and historical genre, typical of an aspiring academic painter. However, even in these early pieces, a penchant for careful observation and a desire for verisimilitude were evident. He competed for the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1876, winning a second prize, which, while not allowing him to study at the French Academy in Rome, was a significant honor that further boosted his reputation.

A pivotal moment in his early career was the exhibition of A Wedding Party at the Photographer's at the Salon of 1879. This painting, depicting a contemporary scene with a touch of gentle humor and keen social observation, marked a shift towards subjects drawn from modern life. It was well-received and demonstrated his growing interest in capturing the nuances of human interaction and everyday occurrences.

The Embrace of Naturalism and Peasant Themes

The late 1870s and early 1880s saw Dagnan-Bouveret increasingly align himself with the Naturalist movement. Naturalism, an artistic and literary movement that emerged as an extension of Realism, sought to depict subjects with scientific objectivity and often focused on the lives of ordinary people, particularly the rural peasantry and urban working class. Artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, a close friend of Dagnan-Bouveret, were leading proponents of this style, creating works like Haymaking (Les Foins) (1877) that presented an unsentimental yet empathetic view of rural labor.

Dagnan-Bouveret's painting The Accident (1879, exhibited Salon 1880) is a quintessential example of his early Naturalist phase. The work depicts a young boy who has injured his hand, being attended to by his concerned family and a local doctor in a rustic interior. The scene is rendered with meticulous detail, capturing the textures of clothing, the worn surfaces of the furniture, and the varied expressions of the figures. The emotional gravity of the moment is palpable, conveyed through subtle gestures and gazes. This work earned him a second-class medal at the Salon, solidifying his reputation as a significant Naturalist painter.

His connection to the Franche-Comté region, his grandfather's homeland, became increasingly important. He spent considerable time there, observing and sketching the local people and their way of life. These experiences provided rich material for his paintings, which often celebrated the dignity of labor and the quiet piety of rural communities. Works like Horses at the Watering Trough (1885) showcase his exceptional ability to render animals with anatomical accuracy and to capture the atmosphere of rural life. The influence of earlier painters of peasant life, such as Jean-François Millet of the Barbizon School, can be felt, though Dagnan-Bouveret's approach was typically more detailed and polished, reflecting his academic training.

The Role of Photography in His Art

Dagnan-Bouveret was among the pioneering artists of his generation to recognize and utilize the potential of photography as a tool in the creative process. While some traditionalists viewed photography as a threat to painting, Dagnan-Bouveret embraced it as an aid to achieving greater accuracy and capturing fleeting moments. He would often take photographs of his models, settings, and preliminary compositions, using these images as references in his studio.

This practice allowed him to study details of costume, gesture, and expression with an unprecedented level of precision. For complex group scenes, photography helped him to arrange figures and to capture authentic poses that might be difficult for models to hold for extended periods. It is important to note that he did not simply copy photographs; rather, he integrated photographic information into his artistic vision, transforming it through his skill in drawing, composition, and color. His use of photography contributed significantly to the heightened realism and immediacy of works like The Accident and his later Breton scenes. This innovative approach, shared by contemporaries like his teacher Gérôme and fellow Naturalist Émile Friant, placed him at the cutting edge of artistic practice.

Breton Scenes and Deepening Religious Conviction

From the mid-1880s, Dagnan-Bouveret turned his attention increasingly to Brittany, a region in northwestern France known for its rugged landscapes, distinctive cultural traditions, and profound Catholic faith. He was particularly drawn to the "pardons," traditional Breton religious festivals involving processions, prayers, and communal gatherings. These events provided him with powerful subjects that combined ethnographic interest with spiritual depth.

His painting The Pardon in Brittany (also known as The Pardon of Saint Anne of La Palud), completed in 1886, is one of his most celebrated masterpieces. It depicts a solemn procession of Breton peasants in traditional costume, their faces etched with devotion as they participate in the religious ritual. The meticulous rendering of the intricate lace coiffes, the textures of the woolen garments, and the varied expressions of piety is remarkable. The painting captures both the collective spirit of the community and the individual faith of its members. This work, along with The Consecrated Bread (1885), which depicts women receiving blessed bread in a Breton church, earned him a medal of honor at the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

These Breton paintings often possess a quiet, contemplative mood, imbued with a sense of timeless tradition. Works like Breton Women at a Pardon (1887) and Madonna of the Rose (1885) further explore themes of faith and maternal devotion within the Breton context. The figures are often portrayed with a serene dignity, their spiritual lives depicted with empathy and respect. Dagnan-Bouveret's religious paintings from this period are characterized by their sincerity and their ability to convey profound spiritual feeling without resorting to overt sentimentality. He managed to fuse the detailed observation of Naturalism with a spiritual intensity that resonated deeply with contemporary audiences.

Masterful Portraiture

Alongside his genre scenes and religious paintings, Dagnan-Bouveret was a highly accomplished portraitist. His skill in capturing a likeness, combined with his ability to convey the personality and social standing of his sitters, made him a sought-after painter among the affluent bourgeoisie and aristocracy. His portraits are characterized by their refined elegance, psychological insight, and meticulous attention to detail in rendering clothing and accessories.

He painted portraits of prominent figures, including fellow artists like Gustave Courtois, his close friend and studio mate, and members of high society. These portraits often go beyond mere likeness, offering a glimpse into the inner life of the subject. His academic training ensured a strong foundation in drawing and modeling, while his Naturalist sensibilities led him to seek out the unique character of each individual. His portraiture, while perhaps less famous than his peasant or religious scenes, demonstrates the breadth of his talent and his adaptability to different artistic demands. Artists like Léon Bonnat were also highly successful portraitists of the era, and Dagnan-Bouveret's work in this genre stands comfortably alongside the best of his contemporaries.

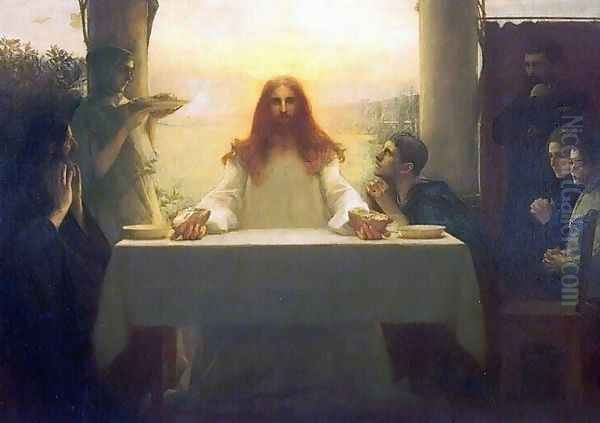

Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus: A Culminating Work

One of Dagnan-Bouveret's most significant later works is Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (1896-1897). This large-scale painting depicts the biblical scene where the resurrected Christ reveals himself to two disciples. The composition is carefully structured, with Christ at the center, bathed in a subtle, ethereal light that distinguishes him from his companions. The disciples, rendered with the artist's characteristic realism, react with awe and recognition.

The setting is a simple, rustic interior, reminiscent of the peasant homes Dagnan-Bouveret often depicted. This choice grounds the sacred event in a familiar, everyday reality, making the miraculous moment more accessible and relatable. The play of light and shadow is masterfully handled, creating a dramatic yet intimate atmosphere. Some art historians have noted a possible influence of Caravaggio in the use of chiaroscuro, though Dagnan-Bouveret's lighting is generally softer and more diffused.

The painting was exhibited to great acclaim and was acquired by the French state, eventually finding its place in the Musée d'Orsay. It represents a culmination of his artistic concerns: the fusion of meticulous realism with profound spiritual content, the careful observation of human emotion, and the masterful handling of composition and light. This work, along with his Breton pardons, cemented his reputation as a leading religious painter of his time, capable of revitalizing traditional themes for a modern audience.

Artistic Circle and Collaborations

Dagnan-Bouveret was well-integrated into the Parisian art world. His training at the École des Beaux-Arts connected him with a generation of artists. His closest artistic friendship was with Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose commitment to Naturalism and plein-air painting was a significant influence. They shared a deep mutual respect and often discussed their artistic ideas.

He also shared a studio for many years with Gustave Courtois, another fellow student of Gérôme. Courtois, like Dagnan-Bouveret, became a successful academic painter and portraitist. Their relationship was further cemented when Dagnan-Bouveret married Anne-Marie Walter, Courtois's cousin, in 1878. This close personal and professional bond with Courtois lasted throughout their lives.

His teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme, remained an important figure, and Dagnan-Bouveret maintained a respectful relationship with him even as his own style evolved. He exhibited regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français, the successor to the official Salon, and was actively involved in various artistic societies. He was respected by a wide range of artists, from traditional academicians like William-Adolphe Bouguereau to fellow Naturalists like Alfred Roll and Léon Lhermitte, and even artists exploring Symbolist tendencies such as Puvis de Chavannes, though Dagnan-Bouveret's own work remained firmly rooted in observable reality.

Later Years, Honors, and Legacy

Dagnan-Bouveret's career was marked by consistent success and numerous accolades. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1885, promoted to Officer in 1891, and then Commander in 1900. In 1900, he was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, succeeding Jean-Jacques Henner. He also received international recognition, being elected an Honorary Foreign Member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1909.

His works were acquired by major museums in France and abroad, and he continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century. While the rise of avant-garde movements like Fauvism and Cubism began to shift artistic tastes away from academic Naturalism, Dagnan-Bouveret remained a respected figure. His later works, such as Ophelia (1910), show a continued engagement with literary and symbolic themes, sometimes with a softer, more atmospheric quality.

He spent his later years primarily in Quincey, in the Haute-Saône region of Franche-Comté, where he had a house and studio. He passed away there on July 3, 1929, at the age of 77.

Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret's legacy is that of a master technician who brought profound empathy and meticulous observation to his subjects. He successfully bridged the gap between the rigorous demands of academic training and the Naturalist impulse to depict the world with unvarnished truth. His paintings of peasant life, particularly his Breton scenes, are celebrated for their ethnographic accuracy, their sensitive portrayal of religious faith, and their sheer artistic skill. While his style might have been eclipsed by modernism during his later life and in the decades following his death, there has been a renewed appreciation for his work and for the achievements of 19th-century academic and Naturalist painters. His art provides an invaluable window into the social, cultural, and spiritual life of late 19th-century France, rendered with a skill and sincerity that continue to resonate with viewers today. His influence can be seen in the work of other painters who focused on rural themes and detailed realism, such as the American painter Daniel Ridgway Knight, who also worked in France.

Conclusion

Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was an artist who deeply understood the human condition. Whether depicting a solemn religious procession, an intimate family moment, or the dignified bearing of a peasant, he imbued his subjects with a quiet intensity and a profound sense of humanity. His commitment to truth in representation, enhanced by his judicious use of photography, combined with his academic discipline, resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. As a leading figure of French Naturalism, he captured the essence of a world undergoing profound social and cultural change, leaving behind a legacy of beautifully rendered images that continue to speak to the enduring values of faith, community, and the dignity of everyday life. His paintings remain a testament to the power of art to observe, record, and elevate the human experience.