Jules Bastien-Lepage stands as a pivotal figure in late 19th-century French art, a painter whose relatively short career left an indelible mark on the transition from academic tradition to modern artistic expressions. He is celebrated as a leading proponent of Naturalism, a movement that sought to depict the world and its inhabitants with unvarnished truthfulness, often focusing on rural life and the everyday struggles of ordinary people. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, emotional depth, and a unique blend of academic technique with plein-air sensitivity, resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to be studied for its profound humanity and artistic integrity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Rural France

Jules Bastien-Lepage was born on November 1, 1848, in the small village of Damvillers, located in the Meuse department of northeastern France. This region, deeply agricultural, provided the foundational experiences and visual vocabulary that would define much of his artistic output. His family was engaged in grape cultivation, and young Jules grew up immersed in the rhythms of rural life, observing the toil and resilience of the local peasantry. This upbringing instilled in him a profound respect for the land and its people.

His artistic inclinations were evident from an early age, nurtured by his grandfather and his father, who, despite their practical vocations, encouraged his talent for drawing. These early sketches often captured scenes from his immediate surroundings – the fields, the farm animals, and the villagers themselves. This direct observation of nature and human activity would become a hallmark of his mature style. The landscapes of Damvillers, with their specific light and atmosphere, became intimately familiar to him and would serve as the backdrop for many of his most famous paintings.

Parisian Training and Academic Aspirations

Recognizing his potential, Bastien-Lepage's family eventually supported his decision to pursue formal art training. He made his way to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the 19th century, and in 1867, he enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. There, he became a student of Alexandre Cabanel, a highly respected academic painter known for his historical and mythological scenes, as well as his elegant portraits. Cabanel's studio emphasized rigorous draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and a polished finish, all of which Bastien-Lepage absorbed.

During his time at the École, Bastien-Lepage, like many aspiring artists, aimed for success in the traditional academic system. He competed for the coveted Prix de Rome, a scholarship that offered a period of study in Italy. Although he made several attempts, notably in 1875 with The Annunciation to the Shepherds (now in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne) and in 1876 with Priam at Achilles' Feet, he never won the grand prize. These early works, while demonstrating his technical skill, still adhered closely to academic conventions. However, his experiences at the École and his exposure to the broader Parisian art scene were crucial in shaping his artistic direction.

The Franco-Prussian War and a Return to Roots

The trajectory of Bastien-Lepage's early career was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Like many young Frenchmen, he was called to serve. He enlisted in a unit of franc-tireurs, irregular military forces. During the conflict, he sustained a serious injury, which necessitated his return to Damvillers to recuperate. This period of convalescence, spent back in his native village, proved to be a turning point.

Removed from the competitive environment of Paris and the strictures of academic subject matter, Bastien-Lepage reconnected with the themes that had captivated him in his youth. The direct, unembellished reality of rural life, the dignity of labor, and the subtle dramas of everyday existence began to assert themselves as compelling subjects for his art. This enforced return to his roots solidified his commitment to depicting the world he knew best, laying the groundwork for his emergence as a leading Naturalist painter.

The Rise of a Naturalist Master

Bastien-Lepage first gained significant public recognition at the Paris Salon of 1874 with his painting Song of Spring, a charming depiction of a peasant girl in a rustic setting. However, it was his Portrait of my Grandfather, also exhibited in 1874, that truly signaled his distinctive approach. This work, characterized by its unflinching realism and psychological insight, showcased his ability to capture individual character with honesty and empathy.

Throughout the 1870s, Bastien-Lepage increasingly focused on scenes of peasant life, often painted en plein air (outdoors) in and around Damvillers. This practice, popularized by the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, and further developed by the Impressionists, allowed him to capture the specific qualities of natural light and atmosphere. However, unlike many Impressionists who prioritized fleeting visual effects, Bastien-Lepage combined this outdoor observation with careful studio work to achieve a high degree of finish and solidity in his figures.

His commitment to truthfulness extended to the emotional and psychological states of his subjects. He sought to convey not just their physical appearance but also their inner lives, their weariness, their quiet contemplation, or their simple joys. This empathetic approach distinguished his work from more sentimental or idealized depictions of rural life.

Artistic Philosophy: Truth, Nature, and Humanity

Bastien-Lepage's artistic philosophy was deeply rooted in the principles of Naturalism, a literary and artistic movement that aimed for objective, almost scientific, representation of reality. Influenced by writers like Émile Zola, Naturalist painters sought to depict contemporary life without idealization or romanticism, often focusing on the working classes and the impact of social and environmental factors on their lives.

He was profoundly influenced by earlier Realist masters such as Gustave Courbet, whose bold depictions of ordinary people and rural scenes had challenged academic conventions in the mid-19th century. The influence of Jean-François Millet, known for his dignified portrayals of peasant labor like The Gleaners and The Angelus, is also undeniable in Bastien-Lepage's choice of subject matter and his sympathetic treatment of his figures.

While he adopted the Impressionists' practice of painting outdoors and their interest in light, he maintained a more traditional approach to form and composition. His figures are solidly modeled, and his compositions, though often seemingly informal, are carefully structured. He famously declared, "I say that the peasant is the most beautiful of subjects, and that is why I prefer to paint him." This statement encapsulates his dedication to finding beauty and significance in the ordinary and the everyday. He believed in "art for life's sake," emphasizing the social and human relevance of art, a stance that sometimes put him at odds with the "art for art's sake" philosophy espoused by some of his contemporaries, including figures associated with Aestheticism like James McNeill Whistler.

Masterpieces of Rural Life: Haymaking and Potato Harvest

Among Bastien-Lepage's most celebrated works are Les Foins (Haymaking), exhibited at the Salon of 1878 (now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris), and Récolte des pommes de terre (Potato Harvest), exhibited in 1879 (now in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne). These paintings exemplify his Naturalist approach and his profound empathy for his subjects.

Haymaking depicts two peasants, a man and a woman, resting in a sun-drenched field after their labor. The woman lies exhausted on her back, her gaze vacant, while the man sits beside her, his expression one of weary contemplation. The painting is remarkable for its unflinching depiction of physical fatigue and its subtle evocation of the harsh realities of agricultural life. The meticulous rendering of the figures, the hay, and the distant landscape, combined with the palpable sense of summer heat and stillness, creates a powerful and immersive image. The work was both praised for its truthfulness and criticized by some for its perceived ugliness and lack of idealization, a common reaction to Naturalist works.

Potato Harvest portrays a woman stooped over, gathering potatoes in a vast, bleak field under an overcast sky. Her posture and expression convey the arduousness of her task. The muted colors and the expansive, empty landscape emphasize her isolation and the relentless nature of her work. Like Haymaking, this painting is a testament to Bastien-Lepage's ability to imbue scenes of ordinary labor with a sense of dignity and profound human significance. These works resonated with a public increasingly interested in social issues and the lives of the working class.

Another significant work in this vein is October: The Potato Gatherers (1878), which similarly focuses on the theme of rural labor, showcasing his consistent dedication to these subjects.

Joan of Arc Listening to the Voices

While best known for his peasant scenes, Bastien-Lepage also tackled historical subjects, albeit with his characteristic Naturalist sensibility. His Joan of Arc Listening to the Voices (1879, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is a prime example. Instead of a glorified, idealized portrayal of the saint, Bastien-Lepage depicts Joan as a young peasant girl in a humble garden setting, her expression one of intense, almost bewildered, spiritual absorption as she seemingly hears the divine call.

The visionary figures of Saints Michael, Margaret, and Catherine appear faintly behind her, rendered with a ghostly transparency that suggests their ethereal nature. The meticulous detail of the garden, painted from his own family garden in Damvillers, grounds the mystical event in a tangible reality. This painting was highly acclaimed for its psychological depth and its innovative approach to a traditional subject, blending historical narrative with an intimate, naturalistic portrayal. It demonstrated his versatility and his ability to apply his principles of truthfulness even to subjects with a strong spiritual or legendary component.

Portraiture: Capturing the Human Soul

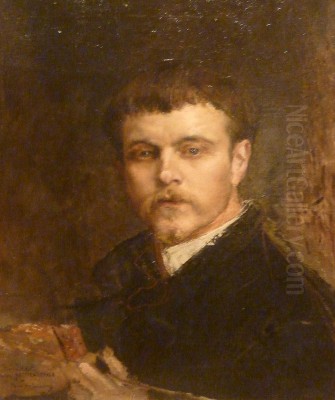

Beyond his genre scenes, Bastien-Lepage was also a highly accomplished portraitist. He brought the same commitment to truthfulness and psychological insight to his portraits as he did to his depictions of peasant life. His sitters included family members, friends, and prominent figures from the artistic and literary worlds.

His Portrait of Madame Juliette Drouet (1883), the long-time companion of Victor Hugo, is a poignant depiction of an aging woman, rendered with sensitivity and respect. Similarly, his Portrait of Albert Wolff (1881), a well-known art critic, captures the sitter's intellectual acuity and strong personality. He also painted a striking portrait of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) in 1879, and the young Sarah Bernhardt (1879), showcasing his ability to move within different social circles while maintaining his artistic integrity.

These portraits are characterized by their directness, their subtle use of color, and their focus on capturing the individual character of the sitter. He often placed his subjects in relatively simple settings, allowing their faces and expressions to convey their personality without distraction. His portrait of his friend, the painter Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, is another fine example of his skill in this genre.

Interactions and Connections in the Art World

Jules Bastien-Lepage was an active participant in the Parisian art scene and maintained connections with many contemporary artists. His relationship with the Impressionists was complex; while he admired their innovations in capturing light and atmosphere, particularly the work of Claude Monet, he did not fully embrace their aesthetic. His commitment to solid form and detailed rendering set him apart.

He was a respected figure among younger artists who were drawn to his Naturalist approach. His close friend, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, shared his interest in rural themes and meticulous technique. Marie Bashkirtseff, a Russian artist living in Paris, deeply admired Bastien-Lepage and wrote extensively about him in her famous diary, considering him a leading light of modern painting. Her own work often shows his influence in its realistic portrayal of contemporary urban and rural life.

His influence extended beyond France. British artists, in particular, were drawn to his work. George Clausen and James Guthrie, leading figures of the Glasgow Boys, were significantly influenced by Bastien-Lepage's subject matter and his technique of combining outdoor observation with studio finish. Stanhope Forbes, a key member of the Newlyn School in Cornwall, also found inspiration in Bastien-Lepage's depictions of rural labor and his commitment to plein-air painting. The Danish painter Peder Severin Krøyer, a prominent member of the Skagen Painters, also knew Bastien-Lepage and his work, which contributed to the broader European trend towards Naturalism and Realism.

International Recognition and Widespread Influence

Bastien-Lepage's work quickly gained international recognition. His paintings were exhibited not only in Paris but also in London and other European capitals, as well as in the United States. His success at the Salons and his growing reputation made him a significant figure in the international art world.

His influence was particularly strong in countries where artists were seeking alternatives to academicism while still valuing representational accuracy. The Newlyn School in England, the Glasgow Boys in Scotland, and even artists in Australia associated with the Heidelberg School, such as Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin, looked to French Naturalism, and Bastien-Lepage specifically, for inspiration in depicting their own national landscapes and everyday life with truthfulness.

His technique, often described as a "compromise" between academic finish and Impressionistic light, offered a path for artists who wanted to engage with modern life without completely abandoning traditional skills. This "juste milieu" (middle way) approach appealed to many. His emphasis on capturing the character of a specific locale and its inhabitants also resonated with artists interested in developing national schools of painting. The impact of his work was further amplified by reproductions and critical discussions in art journals of the period.

Later Years, Premature Death, and Posthumous Recognition

Despite his growing fame and influence, Bastien-Lepage's career was tragically short. He suffered from chronic ill health, possibly exacerbated by the rigors of his work and his war injury. He continued to paint prolifically, dividing his time between Paris and Damvillers. His dedication to his art remained unwavering.

In the early 1880s, his health began to decline more rapidly. He sought treatment, even traveling to Algiers in the hope that a warmer climate might aid his recovery, but to no avail. Jules Bastien-Lepage died in Paris on December 10, 1884, at the young age of 36. His premature death was a significant loss to the art world.

Despite his short life, he had already achieved considerable recognition. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1879. Posthumously, his reputation continued to grow. A major retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1885, organized by his friends and admirers, which further solidified his status. His works were also featured in the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris, showcasing his contribution to French art.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Jules Bastien-Lepage occupies a crucial place in the art history of the late 19th century. He is considered one of the foremost exponents of Naturalism, bridging the gap between the academic tradition of painters like his teacher Cabanel and the emerging modernist movements. He successfully synthesized the meticulous draftsmanship and careful modeling of academic art with the plein-air practices and heightened awareness of light characteristic of Impressionism, creating a style that was both innovative and accessible.

His commitment to depicting the lives of ordinary people, particularly peasants, with honesty and empathy, contributed to a broader shift in artistic subject matter. He elevated scenes of everyday labor and rural life to the status of high art, challenging the traditional hierarchy of genres that favored historical and mythological themes. Artists like Vincent van Gogh, in his early Dutch period, also focused on peasant life, and though their styles differed, they shared a common interest in the dignity of labor and the realities of rural existence. Van Gogh, in fact, owned a print of Bastien-Lepage's Potato Harvest.

Bastien-Lepage's influence on subsequent generations of artists, both in France and internationally, was profound. He provided a model for artists seeking to combine technical skill with a modern sensibility and a commitment to social relevance. While Naturalism as a dominant movement eventually gave way to Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and other avant-garde styles, Bastien-Lepage's emphasis on truthfulness, psychological depth, and the sympathetic portrayal of the human condition remains a powerful and enduring legacy. His work continues to be admired for its technical mastery, its emotional resonance, and its honest depiction of a world that, while rooted in a specific time and place, speaks to universal human experiences.

Conclusion

Jules Bastien-Lepage's art is a testament to his deep connection to his native land and its people. Through his meticulous observation, technical skill, and profound empathy, he created a body of work that captures the essence of rural life in late 19th-century France. As a leading figure of Naturalism, he challenged artistic conventions and expanded the range of acceptable subject matter, paving the way for future generations of artists. Though his life was cut short, his artistic vision and his dedication to "truth in art" ensured his lasting significance in the annals of art history, remembered alongside contemporaries like Édouard Manet for pushing the boundaries of representation, and influencing countless others who sought to capture the realities of their own times.