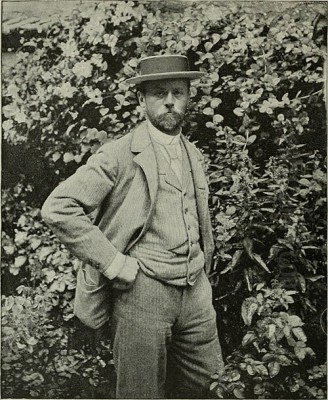

Émile Friant stands as a significant figure in French art during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period of immense artistic ferment and transition. Primarily celebrated as a master of Naturalism, his work meticulously captured the realities of contemporary life, particularly in his native Lorraine, while also displaying a profound psychological depth in his portraiture. His career, marked by early prodigious talent and sustained critical acclaim, offers a fascinating window into the academic art world of the French Third Republic, its values, and its eventual yielding to modernist currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Lorraine

Jean Joseph Émile Friant was born on April 16, 1863, in the town of Dieuze, located in the Moselle department of northeastern France. His family background was modest; his father worked at a local saltworks, and his mother was a seamstress. This upbringing in a working-class environment would later subtly inform his empathetic portrayals of ordinary people and their daily struggles and joys.

The pivotal event of Friant's early childhood was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Following France's defeat and the subsequent annexation of parts of Alsace and Lorraine (including Dieuze) by the German Empire, the Friant family, like many others, chose to remain French citizens. They fled their hometown and resettled in Nancy, a major city in Lorraine that remained part of France and became a haven for refugees from the annexed territories. This early experience of displacement and the strong regional identity of Lorraine would become underlying currents in his life and art.

In Nancy, young Émile's artistic talents quickly became apparent. He was fortunate to find early encouragement and formal training. His precocious abilities led him to the Municipal School of Drawing and Painting in Nancy, often referred to as the École de Nancy, though it's important to distinguish this earlier iteration from the later Art Nouveau movement associated with the same name.

Formative Education: Nancy and Paris

At the Nancy art school, Friant studied under Louis-Théodore Devilly, a respected local painter. Devilly, who had himself studied with an apprentice of the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, provided Friant with a solid foundation in academic techniques, particularly in still life and landscape painting. Friant absorbed these lessons with remarkable speed and skill. His talent was such that by the tender age of fifteen, in 1878, he had his first painting, Le petit Friant (Little Friant), accepted at the local Salon in Nancy, an impressive achievement for an artist so young.

This early success spurred him on. With the support of his patrons in Nancy, Friant set his sights on Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. He gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art in France. There, he entered the studio of Alexandre Cabanel, one of the most powerful and influential academic painters of the era. Cabanel was renowned for his historical, mythological, and allegorical paintings, executed with a polished, idealized finish, as seen in his famous The Birth of Venus.

While Friant dutifully learned the academic curriculum under Cabanel, which emphasized drawing from classical sculpture and the live model, historical compositions, and a smooth, highly finished technique, he found the environment somewhat stifling. His temperament and artistic inclinations were already leaning towards a more direct and unvarnished depiction of reality.

A more profound influence during his Parisian studies came from the work and ethos of Jules Bastien-Lepage. Bastien-Lepage, also from Lorraine (specifically Damvillers), was a leading figure of the Naturalist movement. His paintings, such as Haymaking (Les Foins), depicted rural life with an unsentimental honesty and a keen observation of light and atmosphere, often using a muted palette and a focus on the psychological presence of his subjects. Bastien-Lepage's success in capturing the truth of peasant life resonated deeply with Friant, offering an alternative to the grand historical narratives favored by academicians like Cabanel or Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The Rise of a Naturalist Master

Friant's career began to blossom in the 1880s. He quickly distinguished himself as a painter of remarkable technical proficiency and keen observational skills. His early works demonstrated a commitment to Naturalism, a movement that sought to depict subjects with scientific objectivity and truthfulness, often focusing on everyday life, labor, and the social conditions of the time. This was an extension of Realism, pioneered by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, but Naturalism often incorporated a more detailed, almost photographic, rendering and sometimes a more detached, less overtly political stance.

In 1882, despite his reservations about Cabanel's studio, Friant had two paintings, Intérieur d'atelier (Studio Interior) and L'Enfant prodigue (The Prodigal Son), accepted at the prestigious Paris Salon. The Salon was the official, state-sponsored art exhibition and the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. L'Enfant prodigue earned him a third-class medal, a significant honor for a young artist.

The following year, 1883, marked a major milestone: Friant was awarded the coveted Prix de Rome (second prize) for his painting Œdipe maudissant son fils Polynice (Oedipus Cursing his Son Polynices). The Prix de Rome was a scholarship that allowed promising young artists to study at the French Academy in Rome. While the subject matter was classical, as required by the competition, Friant's treatment likely showed his burgeoning realist tendencies. Though he did not spend the traditional extended period in Rome, the award significantly boosted his reputation.

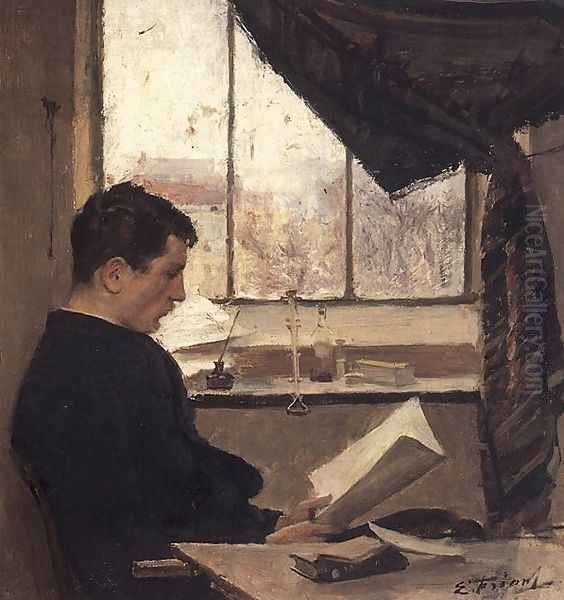

His Salon success continued. In 1884, his Un étudiant (A Student) received a second-class medal. He was increasingly drawn to portraiture and scenes of contemporary life, often set in his beloved Lorraine. He developed a close friendship with other artists from Lorraine, including Victor Prouvé, a versatile artist involved in painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, and Aimé Morot, a painter known for his portraits and historical scenes. These connections reinforced his regional identity and his commitment to depicting the world around him.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Émile Friant's art is characterized by several key features that define his place within the Naturalist movement and highlight his individual strengths.

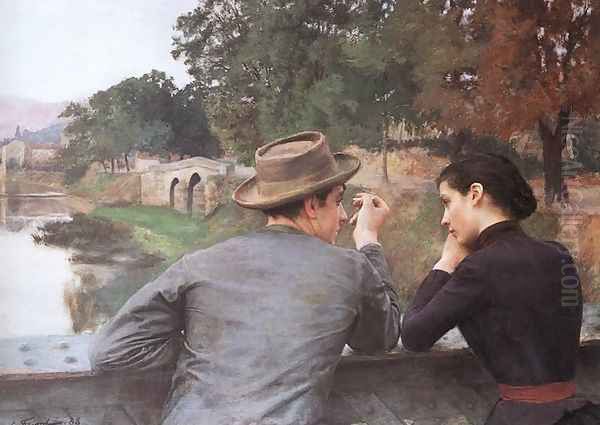

Naturalism and Veracity: At its core, Friant's work is rooted in Naturalism. He aimed to represent his subjects with scrupulous accuracy, paying close attention to anatomical detail, the texture of materials, and the effects of light. His figures are not idealized; they are real people, often with a palpable sense of presence and individuality. He frequently depicted scenes from the lives of ordinary people – students, families, workers, and individuals in moments of quiet contemplation or social interaction.

Technical Virtuosity: Friant was a painter of exceptional technical skill. His draftsmanship was impeccable, and his handling of paint allowed for both meticulous detail and a sense of atmosphere. He could render the subtle play of light on skin, the sheen of fabric, or the rough texture of a stone wall with equal facility. This technical mastery gave his paintings a compelling sense of realism that was highly admired by his contemporaries. Artists like Léon Bonnat and Carolus-Duran, themselves masters of technique, would have recognized Friant's skill.

Psychological Insight: Beyond mere surface representation, Friant's best works, particularly his portraits, reveal a keen psychological insight. He had a remarkable ability to capture the inner life of his sitters, conveying their personality, mood, and social standing through subtle expressions, posture, and the careful arrangement of the composition. His portraits are not just likenesses; they are character studies.

The Influence of Photography: Like many artists of his generation, including Edgar Degas and Gustave Caillebotte, Friant was interested in and utilized photography. He owned a camera and often used photographs as preparatory studies or aides-mémoires for his paintings. This is evident in the sometimes unconventional cropping of his compositions, the sense of a captured moment, and the detailed accuracy of his figures and settings. However, he never slavishly copied photographs; they were tools integrated into his broader artistic vision, which always prioritized painterly qualities and emotional resonance.

Light and Atmosphere: Friant was a master of light. He skillfully used chiaroscuro to model forms and create dramatic effects, but he was equally adept at capturing the more subtle nuances of daylight, whether it was the cool, diffused light of an interior or the brighter light of an outdoor scene. His paintings often have a strong sense of atmosphere, evoking a specific time of day and mood.

Symbolist Undertones: While primarily a Naturalist, some of Friant's later works exhibit Symbolist undertones. Symbolism, a contemporary movement that reacted against Naturalism's strict objectivity, sought to express ideas and emotions through suggestive imagery and symbolic meaning. In some of Friant's paintings, particularly those dealing with themes of love, loss, or contemplation, there is a deeper layer of meaning that transcends straightforward representation.

Orientalism: Like many European artists of the 19th century, Friant experienced a period of fascination with the "Orient." He traveled to Tunisia, and this journey resulted in a number of works depicting North African scenes and people, such as Femmes Juives à Tunis (Jewish Women in Tunis). These paintings, while still demonstrating his characteristic realism, engaged with the popular Orientalist genre.

Key Works in Focus

Several paintings stand out in Émile Friant's oeuvre, exemplifying his style and securing his reputation.

La Toussaint (All Saints' Day, 1888): This is arguably Friant's most famous painting and a quintessential work of French Naturalism. Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1889 (not 1888 as sometimes misdated for the painting itself), it depicts a young widow, accompanied by her daughter and an older woman (likely her mother), visiting a grave on All Saints' Day, a traditional day for honoring the dead. The figures are dressed in mourning black, and their expressions are somber and reflective. The painting is remarkable for its poignant emotional atmosphere, its meticulous rendering of details (the flowers, the textures of the clothing, the dampness of the cemetery), and its sensitive portrayal of grief and familial piety. La Toussaint was a triumph for Friant, winning him a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889 and the Legion of Honor. Its popularity was immense, and it was widely reproduced, making Friant a household name. The work resonated deeply with the public, capturing a common human experience with dignity and empathy.

Les Lutteurs (The Wrestlers, 1889): Also known as La Lutte (The Struggle), this painting showcases a different facet of Friant's talent. It depicts a wrestling match, a popular form of entertainment, with a raw energy and dynamism. The muscular bodies of the wrestlers are rendered with anatomical precision, and the sense of physical exertion is palpable. The crowd surrounding the wrestlers is composed of individuals, each with their own reaction to the spectacle. The work is a powerful example of Friant's ability to capture movement and a sense of immediacy, almost like a photographic snapshot, yet with the rich texture and depth of oil paint.

Chagrin d'Enfant (A Child's Sorrow, 1898): This painting is a tender and insightful depiction of childhood emotion. A young girl, her face buried in her arms, sits at a table, evidently upset. The cause of her distress is unstated, allowing the viewer to empathize with the universal experience of childhood sadness. Friant's ability to convey emotion through posture and subtle detail is particularly evident here.

Portrait de Madame Petitjean (1883): An early example of his skill in portraiture, this work demonstrates his ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the personality and social standing of the sitter. His portraits were highly sought after throughout his career.

Les Amoureux (The Lovers, c. 1888): This painting depicts a young couple in a boat, a common theme in late 19th-century art, explored by artists like Manet and Caillebotte. Friant’s version is imbued with a quiet intimacy and a sense of romantic idealism, showcasing his ability to handle tender, personal moments.

Discussion Politique (Political Discussion, 1889): This work shows Friant engaging with contemporary social themes. It depicts a group of men, likely working-class, engaged in an animated political debate. The painting captures the intensity of their discussion and provides a glimpse into the social and political concerns of the era.

Les Oiseaux Familiers (Familiar Birds, 1921): A later work, this painting shows a more intimate and perhaps slightly more Symbolist-inflected scene. It depicts a young woman feeding birds, a gentle and harmonious image that reflects a continued interest in everyday life and nature.

Professional Recognition and Academic Career

Friant's talent and hard work brought him considerable professional success and recognition within the established art world. His regular participation in the Paris Salon was marked by numerous awards and acquisitions by the state and private collectors.

The gold medal for La Toussaint at the 1889 Exposition Universelle was a major honor, solidifying his position as a leading painter of his generation. He was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor in 1889, a prestigious French order of merit. He would later be promoted to Officer and then Commander of the Legion of Honor in 1931, a testament to his sustained contributions to French art.

His works were acquired by major French museums, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (which now holds La Toussaint) and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy, which has a significant collection of his paintings. He also found patrons internationally, particularly in the United States, facilitated by art dealers like Roland Knoedler. The American industrialist and art collector Henry Clay Frick was among those who acquired his work, and Friant participated in the Carnegie International exhibitions in Pittsburgh.

In 1906, Émile Friant was appointed a professor at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, succeeding his former master, Cabanel, in a teaching role (though Cabanel had passed away in 1889, his teaching lineage continued). This was a position of considerable prestige and influence, allowing him to shape a new generation of artists. He was known as a dedicated and respected teacher.

His career culminated in his election to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, one of the five academies of the Institut de France, in 1923. This was the ultimate recognition for an artist within the French academic system, placing him among the "immortals" of French culture. He took the seat previously held by the painter Luc-Olivier Merson.

Relationships and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Friant maintained strong ties with his native Lorraine and its artistic community. His friendships with Victor Prouvé and Aimé Morot were enduring. He was also part of a broader circle of Naturalist painters who shared similar artistic goals, such as Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, another artist known for his meticulously rendered scenes of peasant life and religious subjects, often with a photographic clarity.

His relationship with his teacher Alexandre Cabanel was complex. While he learned from Cabanel, Friant's artistic path diverged significantly from his master's idealized academicism. Yet, his eventual professorship at the École des Beaux-Arts suggests a reconciliation with, or at least a respected position within, the academic establishment.

He also painted portraits of notable contemporaries, including the sculptor Jean-Louis Burtin, who was a close friend and later became the executor of Friant's will. His circle would have included many of the prominent Salon artists of the day, figures who, like him, navigated the expectations of the official art world while developing their individual styles.

The "Controversy" of Style and the Shifting Art World

While Friant himself was not a figure of personal scandal or overt controversy, his artistic choices placed him within the broader debates of the late 19th-century art world. Naturalism, while popular and critically acclaimed by many, was also seen by some as too literal, lacking the imaginative power of Romanticism or the formal innovation of emerging movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Friant's commitment to a highly finished, detailed realism, even when incorporating photographic aids, was in stark contrast to the Impressionists' emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and color with broken brushwork, or the Post-Impressionists' (like Van Gogh or Gauguin) exploration of subjective expression and formal experimentation.

While Friant achieved great success within the Salon system, this system itself was increasingly being challenged by avant-garde artists who sought alternative venues and modes of expression. Friant, in this context, can be seen as a master of an established tradition, one that valued craftsmanship, verisimilitude, and relatable human themes. He was not an artistic revolutionary in the mold of the Impressionists or later modernists, but rather a superb exponent of a particular artistic vision that had deep roots in the 19th century.

His occasional critique of the more rigid aspects of academic training, stemming from his own student experiences, suggests an independent mind, but one that ultimately worked successfully within the system, reforming it perhaps from within through his teaching and example.

Later Career and Enduring Themes

Friant continued to paint and exhibit throughout the early 20th century. His style remained largely consistent, though some later works show a softening of focus or a more intimate, almost Symbolist sensibility, as seen in Les Oiseaux Familiers. Portraiture remained a significant part of his output, and he was sought after by prominent members of French society.

He remained dedicated to his teaching at the École des Beaux-Arts, influencing students with his emphasis on solid draftsmanship and careful observation. He witnessed the rise of Fauvism, Cubism, and other modernist movements that radically departed from the representational traditions he upheld. While these new movements increasingly dominated the avant-garde, Friant continued to represent a strand of French art that valued continuity, craftsmanship, and a connection to the observable world.

Émile Friant passed away in Paris on June 9, 1932. He was buried in Nancy, returning to the Lorraine region that had shaped him and that he had so often depicted in his art.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Émile Friant is often described as one of the "last Naturalists." His career spanned a period when Naturalism was at its height and then gradually waned in prominence as modernist movements took center stage. For a time, like many academic and Naturalist painters of his era, his reputation was somewhat eclipsed by the focus on the avant-garde.

However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for the art of the 19th-century academic and Naturalist traditions. Art historians and the public have increasingly recognized the technical skill, psychological depth, and historical importance of artists like Friant. His work provides invaluable insights into the society, culture, and artistic values of the French Third Republic.

His paintings are admired for their exquisite craftsmanship, their sensitive portrayal of human emotion, and their honest depiction of everyday life. Works like La Toussaint retain their power to move viewers with their quiet dignity and profound empathy. The influence of photography on his work is also a subject of ongoing interest, highlighting the complex interplay between painting and new technologies in the 19th century.

Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as a major retrospective at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy in 2016, have helped to bring his art to a wider contemporary audience and reaffirm his status as a significant French painter. His legacy is that of a supremely gifted artist who, with integrity and immense skill, chronicled his time and captured the enduring aspects of the human condition. He stands as a testament to the power of representational art to convey truth and beauty, a master whose meticulous eye and empathetic heart created a body of work that continues to resonate.