Paul Dominique Philippoteaux (1845-1923) stands as a significant figure in the annals of 19th-century art, primarily celebrated for his mastery in creating vast, immersive panoramic paintings, or cycloramas. Born in Paris, France, into an artistic family, Philippoteaux inherited a passion for historical and grand-scale depiction from his father, Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, himself a renowned painter of battle scenes and panoramas. This familial influence, combined with the prevailing artistic currents of the era, shaped Paul's career, leading him to produce some of the most impressive and popular visual experiences of his time. His work, predominantly in oils, captured pivotal historical moments with a commitment to accuracy and dramatic flair that captivated audiences across continents.

The 19th century was an age of burgeoning popular entertainment and a thirst for visual knowledge. Historical painting, championed by the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, held a prestigious position. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, with his meticulously detailed Orientalist and historical scenes, and Ernest Meissonier, famed for his precise depictions of Napoleonic battles, set high standards for historical verisimilitude. It was within this cultural milieu that Philippoteaux honed his craft, specializing in a form of art that aimed to transport the viewer directly into the heart of the event. While his name might not be as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries who focused on salon paintings, his impact on popular visual culture, particularly through the cyclorama, was immense.

The Artistic Lineage and Early Career

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux was born on January 27, 1845, in Paris. His father, Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux (1815-1884), was a distinguished artist known for his historical paintings, particularly battle scenes like "The Battle of Rivoli" and "The Last Stand of the Girondins." The elder Philippoteaux was also a pioneer in the creation of cycloramas, large-scale 360-degree paintings designed to create an illusion of reality. This artistic environment undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping young Paul's aspirations and skills. He received his formal art education at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he would have studied under masters of the academic tradition, further refining his draftsmanship and compositional abilities.

Following in his father's footsteps, Paul initially gained recognition for his historical paintings. He collaborated with his father on several projects, learning the intricate techniques required for panoramic painting. This collaborative apprenticeship was vital, as creating a cyclorama was a monumental undertaking, demanding not only artistic talent but also logistical planning and an understanding of perspective on an immense scale. The father-son duo became a formidable team, known for their ability to bring history to life on vast canvases. Their works often focused on dramatic military engagements and significant national events, appealing to a public fascinated by heroism and historical narrative.

The Phenomenon of the Cyclorama

The cyclorama emerged in the late 18th century, invented by the Irish painter Robert Barker. It quickly became a popular form of entertainment and edification, offering an immersive experience akin to modern virtual reality or IMAX cinema. These colossal paintings, housed in specially constructed circular buildings, surrounded the viewer, often enhanced by three-dimensional foreground elements (a diorama) that blurred the line between the painted surface and the viewer's space. This trompe-l'œil effect was central to their appeal. Before the advent of cinema, cycloramas were one of the most effective ways to convey the scale and drama of historical events or distant landscapes to a mass audience.

Artists like Pierre Prévost in France and later, the Philippoteauxs, elevated the cyclorama to a high art form. The creation process was complex, involving meticulous research, numerous sketches, and often a team of assistants working under the direction of the master artist. The canvas itself was enormous, sometimes hundreds of feet in circumference and dozens of feet high, requiring specialized techniques for painting and installation. The subjects were typically grand – famous battles, biblical scenes, or cityscapes – chosen for their dramatic potential and public interest. The success of a cyclorama depended on its ability to convince the viewer they were witnessing the actual event, a feat Philippoteaux would achieve with remarkable success.

The Gettysburg Cyclorama: An American Epic

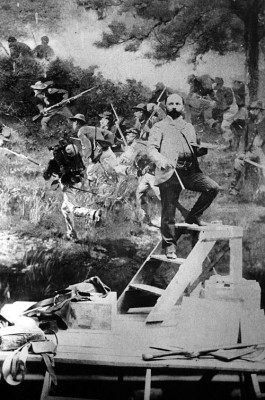

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux’s most enduring legacy is undoubtedly the "Gettysburg Cyclorama," a breathtaking depiction of Pickett's Charge, the climactic Confederate assault on the Union lines on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Commissioned in 1879 by a group of Chicago entrepreneurs, this project would consume several years of Philippoteaux's life and cement his international reputation. Understanding the American public's deep connection to the Civil War, Philippoteaux approached the task with an unwavering commitment to historical accuracy.

To prepare, Philippoteaux traveled to the Gettysburg battlefield in Pennsylvania. He spent several weeks on-site, sketching the landscape, studying the terrain, and absorbing the atmosphere of the historic ground. He hired local photographer William H. Tipton to capture panoramic photographs of the battlefield from various perspectives, which served as crucial visual references. Furthermore, Philippoteaux interviewed numerous survivors of the battle, including Union generals like Winfield Scott Hancock and Abner Doubleday, to gather firsthand accounts and ensure the authenticity of troop movements, uniforms, and battlefield conditions. This dedication to research was a hallmark of his method.

The first version of the "Gettysburg Cyclorama" was completed with the help of a team of five assistants, including his father for certain sections, and it took approximately a year and a half to paint. The colossal canvas, originally measuring around 400 feet in circumference and 50 feet in height (though dimensions varied slightly between versions), was a marvel of illusionistic painting. It depicted the dramatic sweep of Pickett's Charge with thousands of figures, smoke-filled skies, and a meticulously rendered landscape. When it opened in Chicago in 1883, it was an immediate sensation. Spectators flocked to see it, often spending hours marveling at the details and the overwhelming sense of being present at the battle.

The success in Chicago led to the creation of other versions of the Gettysburg Cyclorama. A second version was painted for Boston, opening in 1884, and proved equally popular. This version is the one that survives today, currently housed in the Gettysburg National Military Park. Subsequent versions were exhibited in Philadelphia and Brooklyn. The paintings were typically displayed in purpose-built circular auditoriums, with a central viewing platform. The illusion was enhanced by a three-dimensional diorama in the foreground, featuring real objects like broken fences, cannons, and sculpted figures, which seamlessly blended into the painted scene. This technique, perfected by Philippoteaux, created an astonishingly realistic and immersive experience.

The "Gettysburg Cyclorama" was more than just a popular spectacle; it played a significant role in shaping public memory of the Civil War. For many Americans, particularly those who had not witnessed the war firsthand, Philippoteaux's painting became their definitive image of this pivotal battle. It served as a powerful educational tool and a form of national commemoration. The painting's dramatic intensity and attention to detail resonated deeply with a nation still grappling with the war's legacy. Its popularity can be compared to the historical paintings of American artists like Winslow Homer or Eastman Johnson, who also depicted scenes from the Civil War, though on a much smaller scale.

Other Notable Works and Themes

While the "Gettysburg Cyclorama" remains his most famous work in the United States, Paul Dominique Philippoteaux had a prolific career that encompassed a wide range of historical subjects, particularly military engagements. He created numerous other cycloramas and large-scale paintings depicting significant events in European history. These included scenes from the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), such as "The Battle of Montbeliard," which, like his Gettysburg work, would have involved intensive research and a commitment to capturing the drama and chaos of war. His depictions of this conflict would have resonated strongly in France, much like the works of military specialists Édouard Detaille and Alphonse de Neuville, who were renowned for their patriotic and detailed portrayals of French soldiers.

Philippoteaux also painted scenes from the Napoleonic Wars, a popular subject that allowed for grand compositions and heroic figures, following a tradition established by artists like Baron Antoine-Jean Gros and Horace Vernet. His "French Victory" series and various portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte catered to a continuing fascination with this transformative period in French history. These works showcased his skill in composing complex multi-figure scenes and his ability to convey the pomp and circumstance of military glory, as well as its grim realities.

Beyond military subjects, Philippoteaux explored other historical and even contemporary themes. One notable example is his 1891 oil painting, "The Examination of a Mummy of a Priestess of Amun." This work taps into the 19th-century European fascination with Egyptology, a trend fueled by archaeological discoveries and colonial expansion. The painting depicts a group of scholars and onlookers gathered around an unwrapped mummy, a scene that combines scientific inquiry with a sense of the exotic and the macabre. This interest in ancient Egypt and the "Orient" was shared by many artists of the period, including Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose works often featured meticulously rendered scenes from North Africa and the Middle East. Philippoteaux's painting captures the Victorian era's blend of curiosity, scientific endeavor, and a romanticized view of ancient civilizations.

His diverse portfolio also included works like "The Siege of Paris" (a cyclorama depicting an event from the Franco-Prussian War), "The Battle of Waterloo," "The Battle of Tel-el-Kebir" (depicting a British victory in Egypt), and "The Crucifixion of Christ," displayed in Montreal. Each of these massive undertakings required a similar level of dedication, research, and artistic skill. He often worked with a team of artists, including collaborators like S. Mège and E. Gros, to manage the sheer scale of these projects. The impresario Edward Brandus played a significant role in commercializing and popularizing these cycloramas, even being credited with coining the term "cyclorama" in its popular usage.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Collaboration

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux’s artistic style was firmly rooted in the academic tradition of 19th-century realism, particularly as applied to historical and military painting. His primary goal was to create a convincing illusion of reality, drawing the viewer into the scene as an active participant rather than a passive observer. This was especially crucial for the success of his cycloramas. His technique was characterized by meticulous attention to detail, accurate rendering of figures, uniforms, and landscapes, and a sophisticated understanding of perspective, particularly the complex curvilinear perspective required for a 360-degree canvas.

The creation of a cyclorama was a highly collaborative and industrial process. Philippoteaux would typically be the master artist, responsible for the overall composition, key figures, and critical sections. He would then direct a team of specialized assistants who would paint less critical areas, backgrounds, or specific elements like horses or architectural details, all following his precise instructions and preliminary sketches. This studio system was essential for completing such enormous works within a reasonable timeframe. His father, Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, was a frequent and key collaborator, especially in the early part of Paul's career, sharing his extensive experience in the genre.

Philippoteaux’s research methods were thorough. As seen with the Gettysburg project, he undertook site visits, studied photographs, consulted historical accounts, and interviewed eyewitnesses whenever possible. This commitment to accuracy lent his works an air of authenticity that greatly contributed to their popular appeal. In terms of painting technique, he employed skillful use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model forms and create dramatic effects. His palette was typically rich and varied, capable of depicting everything from the vibrant colors of military uniforms to the somber tones of a smoke-filled battlefield. The brushwork, while necessarily broad in some areas of the vast canvases, could also be remarkably fine in the depiction of faces, expressions, and intricate details that would be scrutinized by viewers.

The illusionistic power of his cycloramas was further enhanced by the physical presentation. The carefully controlled lighting within the cyclorama building, the absence of visible edges to the canvas (the top often hidden by a canopy, the bottom by the three-dimensional foreground), and the sheer scale all contributed to the immersive effect. This was a form of "total art" that engaged the viewer's senses and emotions in a way that traditional easel painting could not. His work can be seen as a precursor to the immersive environments of modern theme parks and the epic scope of cinematic productions.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux occupies a unique place in art history as one of the foremost practitioners of the cyclorama, a popular art form that bridged the gap between academic painting and mass entertainment in the 19th century. While the cyclorama's popularity waned with the rise of cinema in the early 20th century, Philippoteaux's contributions remain significant. His works, particularly the "Gettysburg Cyclorama," are important historical documents in themselves, reflecting not only the events they depict but also the cultural values and visual sensibilities of their time.

His dedication to historical accuracy and his ability to translate complex historical narratives into compelling visual experiences set a high standard for the genre. The "Gettysburg Cyclorama," in particular, has had a lasting impact on American culture, shaping the popular understanding of the Civil War for generations. Its survival and restoration are a testament to its enduring power and historical importance. The painting is not merely an illustration but an interpretation that conveys the human drama and scale of the conflict in a way that few other media could achieve at the time. One might compare its cultural impact to the historical narratives captured by American painters like Thomas Eakins in his realistic portrayals of contemporary life, or the dramatic Western scenes of Frederic Remington, which also helped define American identity.

The technical achievements of Philippoteaux and other cyclorama painters were considerable. They pushed the boundaries of illusionistic painting and perspective, creating immersive environments that were technologically innovative for their era. While many cycloramas have been lost or destroyed due to their size, fragility, and the decline in their popularity, those that survive, like the Gettysburg painting, offer a fascinating glimpse into a forgotten world of popular visual culture. They stand as monuments to a time when painting could be a truly mass-market spectacle.

In the broader context of 19th-century art, Philippoteaux can be seen as an artist who successfully navigated the demands of both artistic tradition and popular taste. He applied the skills and standards of academic historical painting to a medium designed for broad public appeal. His work demonstrates the power of visual storytelling and the enduring human fascination with history. While perhaps not a revolutionary in terms of artistic style in the way Impressionists like Claude Monet or Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh were, Philippoteaux was a master of his chosen craft, creating works that were both technically brilliant and deeply engaging. His legacy lies in the immersive worlds he created, offering a powerful testament to the role of art in shaping collective memory and historical understanding. His father's influence, combined with his own talent and the collaborative efforts with artists like S. Mège and E. Gros, and entrepreneurs like Edward Brandus, ensured that the art of the panorama reached a zenith of popularity and artistic quality. The meticulous realism he pursued echoes the efforts of contemporaries in other countries, such as the Russian battle painter Vasily Vereshchagin, who also sought to convey the stark realities of war.

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux passed away on June 28, 1923, in Paris, leaving behind a legacy of monumental artworks that captured the imagination of a generation. His cycloramas were more than just paintings; they were experiences, transporting viewers to other times and places, and in doing so, they played a vital role in the visual culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.