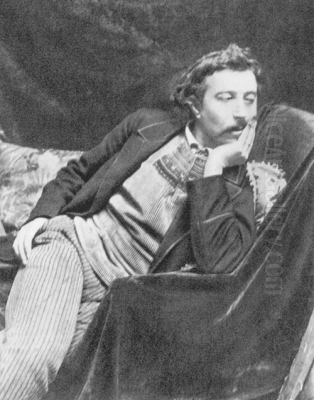

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin remains one of the most fascinating, influential, and controversial figures in the history of modern art. A leading force in Post-Impressionism and a key proponent of Symbolism, his life was as colourful and dramatic as his canvases. Driven by a relentless quest for artistic authenticity and a rejection of European conventions, Gauguin embarked on physical and spiritual journeys that took him from the bustling stock exchange of Paris to the remote islands of the South Pacific. His legacy is a body of work characterized by bold experimentation with colour, simplified forms, and profound symbolic meaning, yet it is inextricably linked to a complex personal life marked by restlessness, hardship, and actions that continue to provoke debate.

Early Life and the Call of Art

Paul Gauguin was born in Paris on June 7, 1848. His early life was touched by adventure and displacement. His father, Clovis Gauguin, was a liberal journalist, and his mother, Aline Chazal, was the daughter of the socialist writer and activist Flora Tristan, who had Peruvian ancestry. Following the political instability after Louis Napoléon's coup d'état in 1851, the family attempted to emigrate to Peru. Clovis tragically died during the voyage, but Aline and her children lived in Lima for several years, an experience that perhaps planted the seeds of Gauguin's later fascination with non-European cultures.

Returning to France, Gauguin received his education in Orléans before joining the merchant marine and later the French Navy, travelling the world for six years. By the early 1870s, he had settled in Paris and embarked on a successful career as a stockbroker. He married a Danish woman, Mette-Sophie Gad, in 1873, and together they had five children. During this period of bourgeois stability, Gauguin began collecting art, particularly works by the Impressionists, and started painting as an amateur.

His passion for art grew steadily, nurtured by his friendship with the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, who acted as an early mentor. Gauguin began exhibiting with the Impressionists, participating in their group shows from the fourth exhibition in 1879 through to the eighth and final one in 1886. Initially, his style reflected the influence of Pissarro and others like Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, focusing on landscapes and scenes of modern life rendered with broken brushwork and attention to light.

However, the stock market crash of 1882 severely impacted Gauguin's financial situation. This crisis, combined with his deepening commitment to art, led him to make a life-altering decision. Around 1883, he resolved to abandon his business career entirely and dedicate himself fully to painting. This choice marked the beginning of a period of financial instability and personal upheaval, eventually leading to the breakdown of his marriage as Mette returned to Denmark with their children. Gauguin's comfortable life was over, replaced by the uncertain existence of a struggling artist.

Breaking with Impressionism: Pont-Aven and Synthetism

Seeking cheaper living conditions and new artistic inspiration, Gauguin began spending time in Brittany, particularly in the village of Pont-Aven, starting in 1886. This region, with its distinct cultural traditions, folk costumes, and rugged landscapes, offered a stark contrast to Parisian life and appealed to Gauguin's growing desire for something more "primitive" and authentic. Pont-Aven became a hub for artists seeking alternatives to Impressionism's focus on capturing fleeting visual sensations.

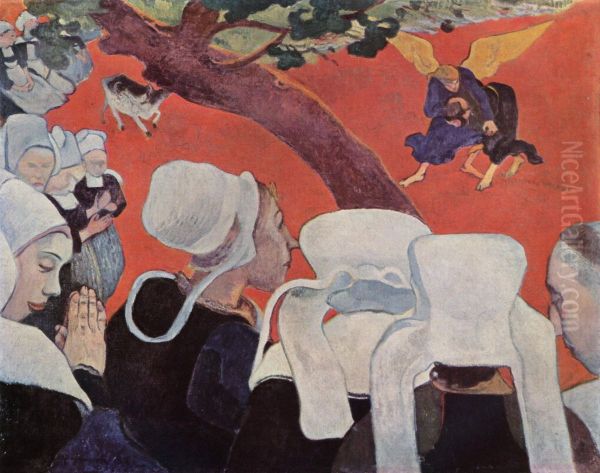

It was here, in collaboration with the younger artist Émile Bernard, that Gauguin developed the style known as Synthetism. This approach moved away from the naturalistic observation of Impressionism towards a style characterized by simplified forms, flattened perspectives, strong outlines, and large areas of bold, often non-naturalistic colour. The aim was not merely to depict the external world but to synthesize observation with feeling, memory, and imagination, conveying ideas and emotions more directly. This style is sometimes also referred to as Cloisonnism, drawing an analogy with cloisonné enamelwork where coloured areas are separated by dark outlines.

Key works from this period exemplify this new direction. The Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel) (1888) is a seminal piece, depicting Breton women in traditional dress witnessing a biblical scene that appears not in the sky, but on a field dramatically rendered in vibrant red. The painting clearly separates the everyday world of the praying women from the spiritual vision, emphasizing subjective experience over objective reality. Another crucial work, The Yellow Christ (1889), portrays a crucifixion scene based on a local wooden crucifix, set against the Breton landscape and painted in stark yellows, greens, and browns, imbuing the religious subject with a sense of rustic piety and symbolic resonance.

During his time in Brittany, Gauguin became the central figure of the Pont-Aven School, influencing artists like Paul Sérusier, whose painting The Talisman, created under Gauguin's direct guidance, became a foundational work for the Nabis group, further disseminating Synthetist ideas. Gauguin's Breton periods were crucial for his artistic maturation, marking his definitive break from Impressionism and establishing the core tenets of his unique visual language.

The Tumultuous Collaboration in Arles

In late 1888, Gauguin embarked on one of the most famous and ill-fated episodes in art history: his two-month stay with Vincent van Gogh in Arles, in the South of France. The arrangement was orchestrated and financed by Vincent's brother, Theo van Gogh, an art dealer who supported both artists. Vincent dreamed of establishing a "Studio of the South," an artists' colony where painters could live and work together, mutually inspiring each other. He saw the more experienced and worldly Gauguin as the ideal leader for this venture.

Initially, the collaboration was productive. Both artists created significant works during this period, influencing each other's palettes and approaches. Gauguin encouraged Van Gogh to work more from memory and imagination, moving away from strict adherence to nature, while Van Gogh's intense emotionalism and vibrant colour likely impacted Gauguin. They painted side-by-side, depicting similar subjects like the Alyscamps Roman necropolis and local figures such as Madame Ginoux, the owner of the Café de la Gare.

However, the fundamental differences in their personalities and artistic philosophies soon led to friction. Van Gogh was volatile, intensely emotional, and sought spiritual solace through direct engagement with nature and humanity. Gauguin was proud, dominant, intellectual, and increasingly focused on symbolic representation derived from imagination. Their debates about art grew heated. Gauguin favoured abstraction and synthesis, while Van Gogh, despite experimenting, remained deeply rooted in observed reality, albeit transformed by his powerful emotions.

The confined space of the "Yellow House," coupled with Van Gogh's deteriorating mental state and Gauguin's perhaps abrasive personality, created an explosive atmosphere. Tensions escalated dramatically in December 1888. Accounts differ, but the generally accepted narrative involves a violent argument. Gauguin claimed Van Gogh threatened him with a razor. Later that evening, in a state of extreme mental distress, Van Gogh infamously cut off part of his own left ear, wrapped it, and delivered it to a woman at a local brothel. Gauguin, finding Van Gogh incapacitated the next morning, summoned the police and promptly left Arles, notifying Theo. The two artists never saw each other again. This traumatic event marked the end of the Studio of the South dream and precipitated Van Gogh's subsequent confinement in an asylum. For Gauguin, it reinforced his desire to escape Europe altogether.

The Quest for Paradise: First Journey to Tahiti

Disenchanted with European civilization, which he viewed as artificial and corrupt, and yearning for a simpler, more authentic existence, Gauguin set his sights on the tropics. Financed partly by the sale of paintings at auction, he travelled to Tahiti, a French colony in the South Pacific, arriving in Papeete in June 1891. He hoped to find an untouched paradise, a primitive society living in harmony with nature, which would provide fresh inspiration for his art.

The reality he encountered was more complex. French colonization had already significantly altered Tahitian culture. Papeete was more Europeanized than he expected, and traditional ways of life were eroding. Seeking a more authentic experience, Gauguin moved to the more rural district of Mataiea. There, he immersed himself in the local environment, took a young Tahitian girl, Teha'amana (or Tehura), as his companion or 'vahine' (a relationship viewed very differently through modern ethical lenses), and began a period of intense artistic production.

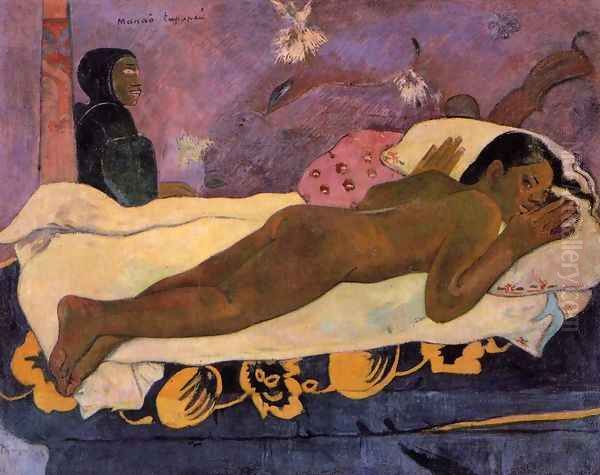

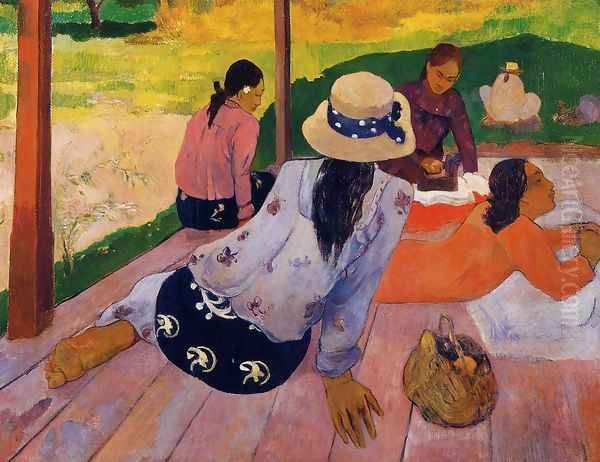

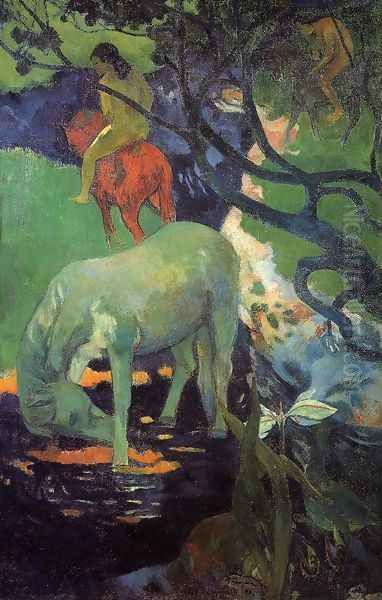

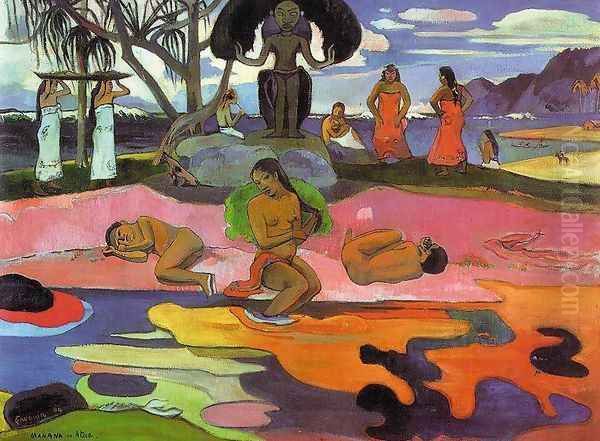

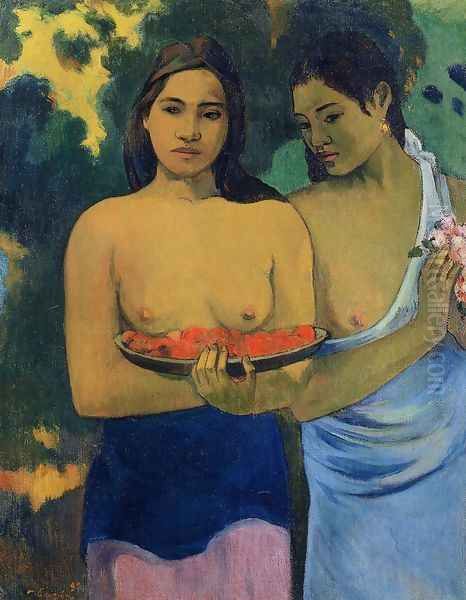

During this first Tahitian stay (1891-1893), Gauguin created some of his most celebrated works. He painted the lush landscapes, the daily lives of the islanders, and particularly the Tahitian women, whom he often depicted with a sense of mystery and quiet dignity. His style continued to evolve, characterized by rich, saturated colours, simplified, monumental forms, and decorative patterns influenced by local art and perhaps Japanese prints. He sought to capture not just the appearance but the perceived spiritual essence of Tahiti.

Paintings like Tahitian Women on the Beach (1891) show his use of flat colour planes and strong outlines to depict figures in repose. Manao tupapau (Spirit of the Dead Watching) (1892), depicting a nude Teha'amana lying fearfully on a bed while a spectral figure watches over her, explores themes of local mythology, fear, and the supernatural, blending observation with imagination and symbolism. Ia Orana Maria (Hail Mary) (1891) merges Christian iconography with Tahitian figures and landscape, reflecting Gauguin's syncretic approach to spirituality. His palette became even bolder, employing evocative juxtapositions of colour to convey mood and meaning. Although he didn't find the completely unspoiled Eden he sought, Tahiti provided Gauguin with the subject matter and environment to fully realize his artistic vision of a world beyond European conventions.

Interlude in France and Return to the Pacific

Running out of funds and suffering from health problems, Gauguin returned to France in August 1893. He arrived with a cache of Tahitian paintings, hoping for critical and financial success. He did achieve a degree of notoriety; an exhibition of his Tahitian works at the Durand-Ruel gallery in Paris generated considerable discussion, though sales were disappointing. Some critics were intrigued by the exoticism and boldness of his work, while others found it crude or incomprehensible. Figures in the Symbolist literary circles, like the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, championed his art.

During this period in Paris, Gauguin cultivated his image as the rebellious "savage," sometimes walking around in Polynesian-inspired attire. He also worked on Noa Noa, a written and illustrated account of his Tahitian experiences, intended to explain his art and philosophy (though its ethnographic accuracy is questionable). He received a small inheritance following the death of an uncle, which provided him with the means to finance another escape from Europe.

Feeling increasingly alienated from the Parisian art world and still longing for the tropics, Gauguin resolved to leave France for good. In 1895, he set sail once more for Tahiti, bidding a final farewell to his wife and children and to European civilization. He declared he wanted to live and die in the Pacific, far from the struggles of the European art market.

Final Years in Tahiti and the Marquesas

Gauguin's second stay in the Pacific (1895-1903) was marked by increasing hardship, illness, and disillusionment, yet it also produced some of his most profound and ambitious works. He found Tahiti further changed and struggled financially. His health deteriorated significantly; he suffered from the effects of syphilis, possibly contracted years earlier, and painful sores on his leg resulting from an ankle fracture sustained during a brawl in Brittany before his departure. He was often in debt and relied on sporadic support from friends and dealers back in France, like Ambroise Vollard.

Despite these difficulties, his artistic drive remained strong. He continued to paint Tahitian subjects, but his work often took on a deeper, more philosophical and melancholic tone. He built a modest house in Punaauia, decorating it with his own wood carvings. His relationship with the colonial authorities and the Catholic mission became increasingly antagonistic; he championed native rights and clashed with officials, leading to legal troubles.

In 1897, facing severe depression exacerbated by news of his daughter Aline's death, poverty, and debilitating health, Gauguin rallied his energy to create his largest and most significant painting, a monumental work he considered his artistic testament: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? This enigmatic, frieze-like composition, populated by figures representing different stages of life and symbolic elements drawn from various cultural sources, poses fundamental questions about human existence, destiny, and the search for meaning. Gauguin stated he intended to commit suicide after completing it, though he failed in the attempt (reportedly using arsenic).

Seeking even greater isolation and perhaps cheaper living, Gauguin moved further afield in 1901 to Atuona, on the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands, another remote part of French Polynesia. Here, he built his final home, which he provocatively named the "Maison du Jouir" (House of Pleasure), adorned with explicit carvings. He continued to paint, sculpt, and make woodcuts, often depicting the Marquesan people. His conflicts with the authorities persisted, culminating in a libel conviction against the local gendarme and bishop shortly before his death.

Artistic Style: Colour, Form, and Symbolism

Paul Gauguin's artistic style is a cornerstone of Post-Impressionism and a vital precursor to several major 20th-century art movements. His work represents a radical departure from the naturalistic aims of Impressionism and a move towards a more subjective, expressive, and symbolic form of art.

Colour: Gauguin's use of colour is perhaps his most distinctive feature. He liberated colour from its descriptive role, employing large, flat areas of intense, often non-naturalistic hues to convey emotion, create decorative patterns, and structure his compositions. He believed colours possessed inherent symbolic and emotional values. His palettes, particularly in his Polynesian works, are rich and resonant, featuring bold juxtapositions of blues, reds, yellows, and greens that create a powerful visual impact. This arbitrary and expressive use of colour would profoundly influence the Fauvist movement, particularly artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain.

Form and Line: Rejecting the Impressionists' dissolution of form through broken brushwork, Gauguin emphasized strong outlines and simplified, often monumental shapes. This approach, known as Cloisonnism or Synthetism (developed with Émile Bernard), involved containing areas of flat colour within clear contours, similar to stained glass or cloisonné enamel. This technique flattened the picture plane, reduced detail, and enhanced the decorative and symbolic qualities of the image. The simplification of form aimed to distill the essence of the subject rather than merely capturing its appearance. This interest in simplified, powerful forms resonated later with Cubists like Pablo Picasso.

Symbolism: Gauguin was a central figure in the Symbolist movement in painting. He sought to imbue his works with deeper meanings, exploring themes of spirituality, life, death, innocence, corruption, and the relationship between humanity and nature. His subjects, whether Breton peasants, Tahitian women, or biblical scenes reinterpreted in exotic settings, often function as symbols for broader ideas. Titles like Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? explicitly point to the philosophical underpinnings of his art. He drew upon Christian iconography, Polynesian mythology, esoteric philosophies, and personal symbolism to create enigmatic and multi-layered works that invite interpretation rather than offering straightforward narratives. His work shares affinities with other Symbolists like Odilon Redon and, in its psychological depth, with Edvard Munch.

Primitivism: Gauguin's fascination with non-Western cultures, particularly those of Brittany and Polynesia, is a key aspect of his art and aligns him with the broader artistic trend of Primitivism. He believed that "primitive" societies possessed a spiritual authenticity and directness that had been lost in modern European civilization. He incorporated stylistic elements, motifs, and subject matter from these cultures into his work, seeking to emulate their perceived simplicity and expressive power. While his engagement with these cultures is now viewed critically for its romanticization and colonial context, his exploration of non-Western aesthetics opened new avenues for European art.

Diverse Media: While primarily known as a painter, Gauguin also worked extensively in other media, including ceramics, wood sculpture, and printmaking, particularly woodcuts. His work in these areas often displays the same bold simplification, expressive power, and interest in "primitive" forms found in his paintings. His innovative woodcuts, with their rough textures and stark contrasts, were particularly influential.

Philosophical and Spiritual Dimensions

Gauguin's art is deeply intertwined with his philosophical outlook and spiritual questing. He was not conventionally religious in his later life, often clashing with Catholic missionaries in Polynesia, yet his work is saturated with spiritual concerns and religious imagery, albeit reinterpreted through his unique lens.

He held a profound disdain for the materialism, hypocrisy, and artificiality he perceived in European society. His flight to the tropics was, in part, a philosophical statement—an attempt to escape the constraints of Western civilization and reconnect with a more fundamental, natural, and spiritually attuned way of life. He idealized the "primitive" as being closer to a state of grace and innocence, although the reality he found often contradicted this romantic notion.

His engagement with religion was complex and syncretic. He drew upon Christian narratives, as seen in The Yellow Christ or Ia Orana Maria, but often infused them with elements of local belief systems or personal symbolism, stripping them of orthodox dogma and using them to explore universal human themes. He was interested in comparative religion and mythology, seeking common threads of spiritual understanding across different cultures. His writings, particularly Noa Noa, reveal an interest in Tahitian cosmology and beliefs, though filtered through his own interpretations and artistic needs.

Symbolism was the primary vehicle for his philosophical explorations. Through suggestive imagery, evocative colour, and enigmatic compositions, he grappled with fundamental questions about human existence: the cycle of life and death, the nature of good and evil, the search for meaning, and the relationship between the physical and spiritual realms. His masterpiece, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, serves as a grand summation of these existential inquiries, presenting a visual allegory of the human condition. Gauguin sought an art that spoke to the soul, not just the eye, aiming to convey profound truths through intuition and suggestion rather than literal representation.

Death and Lingering Questions

Paul Gauguin died on May 8, 1903, in Atuona, Hiva Oa, Marquesas Islands, at the age of 54. He died relatively alone and impoverished in his "Maison du Jouir." The official cause of death was likely related to complications from syphilis and possibly heart failure, perhaps exacerbated by morphine usage, which he took for pain relief.

However, the circumstances surrounding his death have been subject to some speculation and rumour over the years. Given his history of depression, health problems, financial struggles, and a previous suicide attempt (after completing Where Do We Come From?), the possibility of suicide or intentional overdose cannot be entirely dismissed, although the prevailing view points to illness. Some accounts mention he died shortly after being sentenced to prison and fined for libeling the colonial governor, adding another layer of drama to his final days, though he died before potentially serving the sentence. Wild theories, such as poisoning, lack credible evidence but contribute to the mystique surrounding his demise.

What is certain is that Gauguin died far from the European art world that was only beginning to appreciate his genius. His final years were marked by physical suffering, financial hardship, and conflict, a stark contrast to the idyllic paradise he had initially sought. His grave is in the Calvary Cemetery overlooking Atuona, later joined by that of the Belgian singer Jacques Brel, another European who sought refuge in the Marquesas.

Legacy and Influence

Despite limited recognition during his lifetime, Paul Gauguin's influence on the course of 20th-century art has been immense. Following his death, his reputation grew rapidly, thanks in part to retrospective exhibitions and the efforts of dealers like Ambroise Vollard. He is now universally acknowledged as a giant of Post-Impressionism and a pivotal figure in the transition to modern art.

His radical use of colour directly inspired the Fauves, including Henri Matisse and André Derain, who pushed his experiments with non-naturalistic hues even further. His emphasis on subjective expression, emotional intensity, and simplified forms resonated deeply with the German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the artists of the Die Brücke group.

Gauguin's structural simplification of form and his interest in non-Western art (Primitivism) also had an impact on the development of Cubism. Pablo Picasso, in particular, admired Gauguin's sculptures and his ability to convey raw power through simplified shapes, which informed Picasso's own explorations, notably leading up to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Beyond specific movements, Gauguin's broader legacy lies in his assertion of the artist's right to depart from visual reality in favour of personal expression, imagination, and symbolic meaning. He helped shift the focus of art from objective representation to subjective experience, paving the way for abstraction and many other modernist innovations. His life story, that of the rebellious artist rejecting bourgeois conventions to pursue an uncompromising vision in exotic locales, has also contributed to his enduring, albeit romanticized, legend.

Controversies and Critical Reassessment

While Gauguin's artistic importance is undisputed, his life and work have become subjects of intense critical scrutiny and controversy in recent decades, viewed through the lenses of post-colonial theory, feminism, and contemporary ethics.

His relationship with Polynesian culture is now widely seen as problematic. Critics argue that his depiction of Tahiti and its people, particularly women, perpetuates colonial stereotypes of the "exotic," sensual, and primitive Other. He has been accused of cultural appropriation, taking elements from a culture he didn't fully understand and reshaping them to fit his own artistic and personal fantasies, often ignoring the damaging impact of colonialism on the society he claimed to admire.

His personal conduct, especially his relationships with very young Tahitian girls (Teha'amana was reportedly around 13 when their relationship began), is now widely condemned as exploitative and potentially pedophilic by modern standards. His abandonment of his wife and children in Europe to pursue his artistic ambitions is also viewed critically. These aspects of his biography complicate the reception of his art, raising difficult questions about the relationship between an artist's life and their work, and whether it is possible or desirable to separate the two.

Exhibitions and scholarship increasingly grapple with these issues, attempting to present a more nuanced picture of Gauguin that acknowledges both his artistic innovations and the troubling ethical dimensions of his life and engagement with Polynesia. The debate continues regarding how to appreciate his powerful art while confronting the uncomfortable truths about the man and the historical context in which he worked. This ongoing reassessment reflects broader shifts in cultural attitudes towards colonialism, race, and gender.

Conclusion: A Complex and Enduring Figure

Paul Gauguin remains a towering figure in art history, an artist whose bold experiments with colour, form, and symbolism irrevocably changed the direction of modern painting. His quest for a more authentic, spiritual art led him on a remarkable journey from the heart of European modernity to the fringes of the colonial world. The works he produced, particularly during his time in Brittany and the South Pacific, possess an enduring power, beauty, and mystery.

Yet, Gauguin is also a deeply complex and contradictory figure. His life was one of rebellion and restlessness, marked by personal sacrifices, profound hardships, and actions that are ethically troubling by contemporary standards. His artistic vision was intertwined with a romanticized and arguably exploitative view of non-Western cultures, reflecting the colonial attitudes of his era. Understanding Gauguin requires acknowledging both his immense artistic contributions and the problematic aspects of his biography and worldview. He remains a subject of fascination and debate, a testament to the enduring power of his art and the complexities of judging historical figures through the lens of evolving cultural values.