Henri Julien Félix Rousseau stands as one of the most unique and intriguing figures in the history of modern art. A French Post-Impressionist painter, he is celebrated for his captivating, dreamlike depictions of jungle scenes, portraits, and landscapes, rendered in a style often described as Naïve or Primitive. Despite lacking formal artistic training and facing considerable ridicule during his lifetime, Rousseau's unwavering vision and innate talent eventually earned him the admiration of the Parisian avant-garde and secured his place as a pivotal influence on subsequent generations of artists. His journey from a humble toll collector to a celebrated, albeit unconventional, master is a testament to the power of individual creativity.

Early Life and Unconventional Beginnings

Henri Rousseau was born on May 21, 1844, in Laval, Mayenne, France, into a family of modest means. His father worked as a tinsmith and plumber. Financial difficulties marked his childhood, particularly after his father faced bankruptcy. Rousseau attended Laval High School, where he showed aptitude in drawing and music, winning awards for both subjects. However, his academic performance was otherwise unremarkable, and his path did not initially lead toward an artistic career.

In 1863, seeking structure or perhaps escape, Rousseau joined the army. He served for four years, primarily as a bandsman. Contrary to romantic legends he later cultivated – suggesting service in Mexico supporting Emperor Maximilian – there is no credible evidence he ever left France during his military tenure. This period likely provided discipline but little direct artistic stimulation, and he reportedly saw no active combat.

Following his father's death and his discharge from the army, Rousseau moved to Paris in 1868. He married his first wife, Clémence Boitard, a seamstress, the following year. To support his growing family, he took up a position with the Paris toll service, the octroi. This municipal job involved inspecting goods entering the city to levy taxes. It was this role that later earned him the affectionate, if slightly inaccurate, nickname "Le Douanier" (the Customs Officer), bestowed upon him by his friend, the writer Alfred Jarry. Though he worked for the city's tax authority, not the national customs service, the moniker stuck, adding to his persona as an unassuming 'everyman' artist.

The Path of Self-Discovery

For many years, painting remained a passionate hobby pursued alongside his demanding job and family responsibilities. Rousseau was largely self-taught. He claimed to have "no teacher other than nature," though he did receive some informal advice from established academic painters like Félix Auguste Clément and Jean-Léon Gérôme. However, his primary education came from direct observation and diligent practice.

He obtained permits to copy artworks in the great Parisian museums, particularly the Louvre and the Musée du Luxembourg. There, he studied the techniques of the Old Masters and contemporary academic painters, absorbing lessons in composition and form, even if he ultimately diverged radically from their conventions. He was also a frequent visitor to the Jardin des Plantes, Paris's botanical garden, and its associated Ménagerie (zoo). These locations became crucial sources of inspiration, providing him with the exotic flora and fauna that would populate his most famous works.

It wasn't until 1893, at the age of 49, that Rousseau retired from his toll collector position to dedicate himself entirely to his art. This decision marked a significant turning point, allowing him the freedom to fully explore his unique artistic vision, despite the financial insecurity it entailed. His life had already been marked by personal tragedy; his wife Clémence had died in 1888, and only one of their several children, Julia, survived into adulthood. He would later remarry, to Josephine Noury, in 1898.

The Naïve Vision: Style and Technique

Rousseau's style is instantly recognizable and defies easy categorization, though he is generally placed within Post-Impressionism. It is most often labeled "Naïve" or "Primitive," terms that acknowledge its departure from academic naturalism but can sometimes carry condescending undertones, which Rousseau himself rejected. He saw himself as a realist, albeit one depicting a world filtered through his potent imagination.

His paintings are characterized by a deliberate flatness of form, lacking the conventional use of perspective and chiaroscuro (modeling with light and shadow) taught in art academies. Figures and objects often appear sharply outlined, arranged in layered planes rather than receding smoothly into deep space. This creates a decorative, tapestry-like effect. His use of color is bold, vibrant, and often non-naturalistic, contributing to the dreamlike or otherworldly quality of his scenes.

Rousseau applied paint meticulously, often with fine brushstrokes, giving surfaces a smooth, detailed finish. There's a certain stiffness or rigidity in his figures, whether human or animal, which adds to the stylized, almost ceremonial feel of his compositions. Despite these "naïve" qualities – the perceived errors in scale, proportion, and perspective – his works possess a powerful internal logic, compositional strength, and undeniable poetic charm. He compensated for his lack of formal training with an extraordinary sense of design and an intuitive grasp of visual storytelling. He also reportedly used less expensive student-grade paints, which might have contributed to the distinct matte finish and intense hues seen in some works.

The Lure of the Jungle

Undoubtedly, Henri Rousseau is best known for his jungle scenes. Paintings like Surprised! (Tiger in a Tropical Storm) (1891), The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (1905), Tropical Forest with Monkeys (1910), and his final masterpiece, The Dream (1910), transport the viewer to lush, exotic worlds teeming with oversized plants, hidden beasts, and mysterious figures.

The great irony, as mentioned earlier, is that Rousseau never left France. He never witnessed a real jungle. His fantastical visions were entirely constructed from secondary sources. He drew heavily upon illustrations found in popular magazines like Magasin Pittoresque, botanical textbooks, and accounts of exploration. His visits to the Jardin des Plantes were paramount; he would spend hours sketching the tropical plants in the greenhouses and observing the animals in the zoo. Ethnographic displays and colonial exhibitions popular in Paris at the time also likely fueled his imagination.

These jungle paintings are not accurate botanical or zoological records. Instead, they are imaginative syntheses, dreamscapes where familiar elements are exaggerated and recombined to create scenes of wonder, mystery, and sometimes, primal terror. The scale is often distorted, with flowers blooming larger than life and foliage forming dense, impenetrable walls. Animals peer out with wide, unnerving eyes. These works tap into a fin-de-siècle fascination with the exotic and the 'primitive,' but filtered through Rousseau's uniquely innocent and imaginative lens.

Beyond the Jungle: Portraits and Landscapes

While the jungle scenes cemented his fame, Rousseau's oeuvre encompasses a broader range of subjects. He was a distinctive portraitist. His Myself: Portrait-Landscape (1890) is a fascinating self-representation, placing the artist, palette in hand, before a stylized view of Paris, complete with the Eiffel Tower and a hot air balloon. He painted portraits of friends, acquaintances, and sometimes commissioned subjects, such as the writer Pierre Loti (Portrait of Monsieur X (Pierre Loti), c. 1906). These portraits share the stylistic hallmarks of his other works: flattened forms, sharp outlines, intense gazes, and meticulous attention to detail, particularly in clothing and setting.

Rousseau also painted numerous landscapes, often depicting the environs of Paris. These works, like View of the Malakoff District (c. 1908) or views along the Seine, showcase his ability to imbue even mundane suburban scenes with a sense of quiet poetry and formal rigor. He developed a specific subgenre he called "portrait-landscape," where a figure was prominently featured within a detailed landscape setting, giving equal importance to both elements.

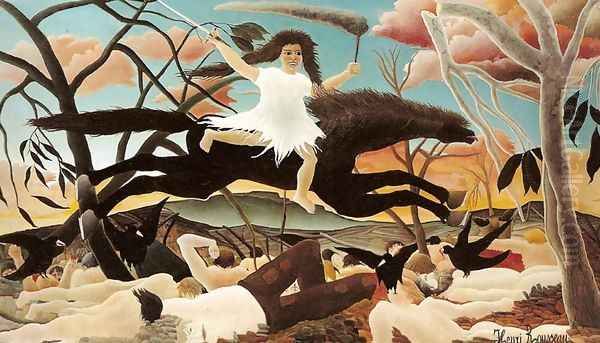

His painting War (1894) stands apart. Exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, it depicts a fearsome, Bellona-like figure riding a black horse across a landscape littered with corpses, while crows feast on the dead. It's a stark, allegorical image, possibly reflecting anxieties of the era or personal reflections on conflict, rendered with his characteristic stylization but conveying a powerful sense of horror.

Masterpieces in Focus: The Sleeping Gypsy and The Dream

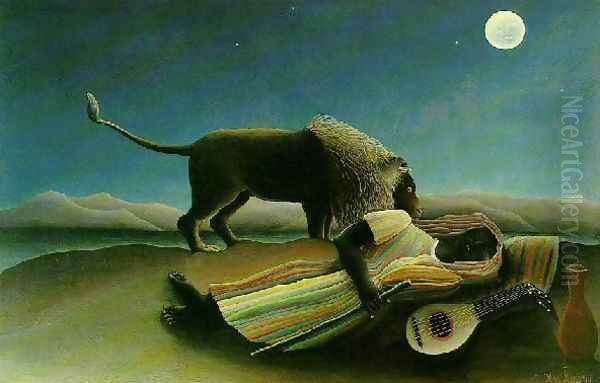

Two paintings, in particular, encapsulate Rousseau's unique genius: The Sleeping Gypsy (1897) and The Dream (1910).

The Sleeping Gypsy presents a stark, moonlit desert landscape. A dark-skinned figure, the gypsy, lies asleep on the sand, clad in colorful striped robes, a mandolin and water jar beside her. Standing over her, seemingly contemplating her, is a lion. The scene is rendered with haunting simplicity. The forms are clearly defined, the colors deep and resonant under a luminous full moon. The relationship between the lion and the sleeping figure is ambiguous – is it protective, curious, or menacing? This enigmatic quality, combined with the poetic atmosphere and masterful composition, makes it one of Rousseau's most iconic and debated works. He offered to sell it to the mayor of his hometown, Laval, but was politely refused; it now resides in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The Dream, exhibited shortly before his death in 1910, is arguably the culmination of his artistic vision, particularly his jungle theme. It depicts a nude woman reclining on a Victorian sofa inexplicably placed in the midst of a dense, vibrant jungle. Exotic birds, monkeys, elephants, and a lion peer through the foliage, while a dark-skinned musician plays a pipe. Rousseau explained the scene with a short poem, describing a woman named Yadwigha who, having fallen asleep on the sofa, dreams she is transported to this forest, listening to the charmer's tune. The painting is a stunning orchestration of lush vegetation, fantastical creatures, and dream logic. It combines the exoticism of the jungle with a mysterious, sensual narrative, executed with breathtaking detail and vibrant color. It is considered his final masterpiece and a powerful testament to his imaginative powers.

Exhibitions, Ridicule, and Avant-Garde Admiration

Rousseau began exhibiting his work regularly at the Salon des Indépendants starting in 1886. This annual, unjuried exhibition was a crucial venue for artists operating outside the official Salon system, including Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and other Post-Impressionists. For years, Rousseau's submissions were met with bewilderment and ridicule from the public and most critics, who dismissed his style as childish, incompetent, and clumsy. They mocked his "errors" in perspective and anatomy, failing to recognize the sophisticated design and emotional power underlying the unconventional technique.

Despite the widespread scorn, Rousseau remained remarkably confident in his own abilities. He genuinely believed he was one of the greatest painters of his time. Gradually, his work began to attract the attention of a small but influential circle of younger, avant-garde artists and writers who saw beyond the surface "naïveté." Figures like the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire became staunch defenders and friends.

Artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, and Constantin Brâncuși recognized the originality and expressive force in Rousseau's work. They admired its directness, its freedom from academic constraints, and its powerful imaginative quality. His bold use of color and flattened forms resonated with the developing currents of Fauvism and Cubism. Picasso, famously, discovered a Rousseau portrait being sold cheaply as canvas to be painted over; he bought it and treasured it.

The Banquet Rousseau

The growing respect among the avant-garde culminated in a legendary event in 1908: the "Banquet Rousseau." Organized by Picasso in his Bateau-Lavoir studio in Montmartre, this semi-burlesque, semi-serious dinner party was held in Rousseau's honor. The guest list included Guillaume Apollinaire, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Georges Braque, André Salmon, Marie Laurencin, and others pivotal to the burgeoning modern art scene.

The evening was a chaotic mix of genuine tribute and playful mockery. Poems were read, speeches were made (some perhaps tongue-in-cheek), and Rousseau himself, seated on a makeshift throne under a banner proclaiming "Honor to Rousseau," played a waltz on his violin. Despite the somewhat ambiguous tone of the event, it symbolized the avant-garde's embrace of Rousseau as one of their own – a visionary precursor whose 'primitive' style was seen not as a failing, but as a source of authentic artistic power. It marked a significant moment of recognition for the aging artist, who had endured decades of misunderstanding.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

In his final years, Rousseau continued to paint with dedication, producing some of his most celebrated works. He supplemented his meager income by giving art and music lessons. His life remained financially precarious, and he was even briefly imprisoned in 1907 due to involvement in a bank fraud scheme, seemingly more as a naive dupe than a criminal mastermind; friends like Apollinaire helped secure his release.

Henri Rousseau died on September 2, 1910, from complications following a leg infection (gangrene). He was buried in a pauper's grave. Seven friends attended his funeral. Later, the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, another admirer, carved an epitaph written by Apollinaire onto his tombstone.

Despite the humble circumstances of his life and death, Rousseau's influence grew exponentially in the years that followed. His work was championed by artists and critics who saw him as a crucial figure in the development of modern art. The Fauves, including Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck, were drawn to his bold, subjective use of color and simplified forms.

The Surrealists, such as Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Giorgio de Chirico, found inspiration in the dreamlike, illogical juxtapositions and mysterious atmospheres of his paintings, particularly The Sleeping Gypsy and The Dream. They saw him as a precursor who tapped into the subconscious long before their movement formalized its exploration. Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract art, also expressed admiration for Rousseau's spiritual and intuitive approach to painting.

Conclusion: An Unlikely Modern Master

Henri Rousseau's story is remarkable. He was an artist who operated outside the established systems of training and patronage, forging a unique path driven by personal vision and unwavering self-belief. Initially dismissed as an eccentric amateur, his "naïve" style was eventually recognized as a sophisticated and powerful form of artistic expression. His fantastical jungles, enigmatic portraits, and poetic landscapes opened up new possibilities for painting, challenging conventions of perspective, form, and subject matter.

By bridging the 19th-century world of popular illustration and academic tradition with the burgeoning modernism of the early 20th century, Rousseau became an unlikely hero to the avant-garde. His influence extended far beyond his lifetime, touching movements from Fauvism and Cubism to Surrealism and beyond. Artists like Picasso, Léger, Kandinsky, and countless others saw in his work a purity, an authenticity, and an imaginative freedom that resonated deeply with their own artistic quests. Henri "Le Douanier" Rousseau remains a beloved figure, a testament to the fact that profound artistic achievement can arise from the most unexpected of origins. His work continues to enchant and inspire, inviting viewers into a world governed by dreams, mystery, and the enduring magic of the untutored eye.