Paul Kleinschmidt stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure within the vibrant landscape of German Expressionism. Born in 1883 and passing away in 1949, his life spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and profound socio-political upheaval in Germany. Kleinschmidt carved a unique niche for himself, primarily known for his powerful, often voluptuous depictions of the female form, alongside compelling still lifes and landscapes. His work navigates the territory between Expressionism's emotional intensity, Realism's grounding, and the sharp focus of New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), marked by a distinctive use of color and a palpable sense of physicality. His journey, however, was fraught with challenges, including persecution under the Nazi regime, exile, and the destruction of much of his oeuvre, adding layers of complexity to his artistic legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Paul Kleinschmidt was born on July 31, 1883, in Bublitz, Pomerania, then part of the German Empire (now Bobolice, Poland). His artistic inclinations led him to formal training at the prestigious Berlin Academy of Art. There, he studied under Anton von Werner, a prominent history painter known for his traditional, academic style. This initial grounding provided Kleinschmidt with technical proficiency, but his artistic spirit sought more modern forms of expression.

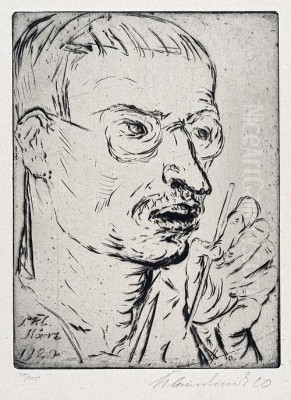

Seeking different influences, Kleinschmidt moved to the Munich Academy. In Munich, a rival center for artistic innovation, he studied under notable figures like Heinrich von Zügel, celebrated for his Impressionistic animal paintings and landscapes, and Peter Halm, a respected etcher and professor. This period likely broadened his technical skills, particularly in drawing and printmaking, which would remain important throughout his career. His time in Munich exposed him to the dynamic currents swirling within the German art scene at the turn of the century.

A pivotal moment in his development came when he returned to Berlin and undertook further studies with Lovis Corinth between 1904 and 1905. Corinth, a leading figure who bridged Impressionism and Expressionism, exerted a considerable influence on Kleinschmidt. Corinth's own robust brushwork, bold use of color, and often dramatic subject matter resonated with the younger artist. Early works by Kleinschmidt show an appreciation for the textured surfaces and emotional intensity found not only in Corinth's work but also in that of Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, whose expressive power was being increasingly recognized.

Berlin Secession and Early Career Development

Kleinschmidt's burgeoning talent found an early platform within the Berlin Secession movement. Founded in 1898 as a progressive alternative to the conservative, state-sponsored art establishment dominated by figures like Kleinschmidt's former teacher, Anton von Werner, the Secession championed modern art styles, including German Impressionism and burgeoning Expressionist tendencies. Led by artists such as Max Liebermann, Walter Leistikow, and Kleinschmidt's mentor Lovis Corinth (who later became its chairman), the Secession provided crucial exhibition opportunities for avant-garde artists.

Kleinschmidt participated in the Berlin Secession exhibitions, notably in 1908 and 1911. This involvement placed him firmly within the modernist circles of the German capital. During these years, he honed his skills, particularly in graphic arts. He became proficient in techniques like etching and drypoint, mediums well-suited to the linear energy and expressive potential favored by many modern artists. His graphic works often explored similar themes to his paintings but with a distinct linear quality.

His reputation began to solidify in the early 1920s. He secured his first solo painting exhibition in 1923 at the Euphorion Gallery in Berlin, followed by another significant show at the prestigious Gurlitt Gallery in 1925. These exhibitions marked his arrival as a distinct voice. He also began to connect with influential figures in the Berlin art world, such as Curt Glaser, a respected art historian and director of the Berlin Kunstbibliothek (Art Library), and Julius Meier-Graefe, a highly influential art critic and historian who championed Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. These connections helped raise his profile within critical and curatorial circles.

The Weimar Years: Defining Themes and Style

The Weimar Republic era (1919-1933) was a period of intense cultural ferment and social change in Germany, particularly in Berlin. Kleinschmidt's art from the 1920s vividly reflects the atmosphere of this time. He became particularly known for his depictions of urban life, focusing on the city's vibrant, often hedonistic, nightlife. Cafes, bars, theaters, circuses, and backstage dressing rooms became his frequent settings.

Within these milieux, Kleinschmidt focused intensely on the human figure, especially women. His subjects often included barmaids, dancers, actresses, prostitutes, and circus performers – figures existing on the margins or at the heart of the city's entertainment world. Unlike the biting social satire found in the works of contemporaries like George Grosz or Otto Dix, who used sharp lines and caricature to critique the era's decadence and corruption, Kleinschmidt's approach was generally less overtly political and more focused on capturing a certain raw vitality and sensuous presence.

His style during this period consolidated into a powerful form of Expressionism blended with elements of Realism. He employed bold, often non-naturalistic colors applied with vigorous brushstrokes, creating rich, textured surfaces that gave his paintings a distinct physical presence. He masterfully manipulated light and shadow to model form and create dramatic effects. While rooted in observation, his figures were often simplified or slightly exaggerated to enhance their expressive impact, aligning him with the broader aims of German Expressionism as practiced by artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Emil Nolde, though Kleinschmidt maintained a stronger connection to representational solidity.

The Female Form: Obsession and Expression

The depiction of the female figure is arguably the most central and recognizable aspect of Paul Kleinschmidt's oeuvre. He returned to this subject repeatedly, developing a highly characteristic portrayal. His women are typically depicted as full-figured, even monumental, possessing a powerful physical presence that dominates the canvas. They are often shown in intimate settings – dressing rooms, cafes, boudoirs – sometimes partially clothed or in elaborate costumes.

These portrayals are complex and open to interpretation. On one hand, they convey a sense of earthy vitality, sensuality, and uninhibited presence, celebrating the physical body. Kleinschmidt seemed fascinated by the textures of flesh, fabric, and makeup, rendering them with a palpable, almost tactile quality through his thick application of paint. His use of strong, warm colors – reds, oranges, pinks – further enhances this sensuous appeal. These figures can be seen as embodying a certain modern female archetype, confident and self-aware within the urban environment.

On the other hand, the intensity of focus and the sometimes-confined spaces can also suggest vulnerability or objectification, reflecting the complex social position of women in the Weimar era. Kleinschmidt's perspective seems observational yet deeply subjective, filtering the world of Berlin's demimonde through his distinct artistic temperament. Works like Bar Girl or the 1921 drypoint Frau, sitzende vor Spiegel (Woman Sitting before Mirror) exemplify his focus on the female form, capturing moments of introspection or public display with his characteristic blend of robustness and sensitivity. This thematic focus aligns him with other Expressionists like Kirchner or Max Beckmann, who also explored the figure within modern urban contexts, though Kleinschmidt's treatment remained uniquely his own.

Still Life and Landscape: Expanding Horizons

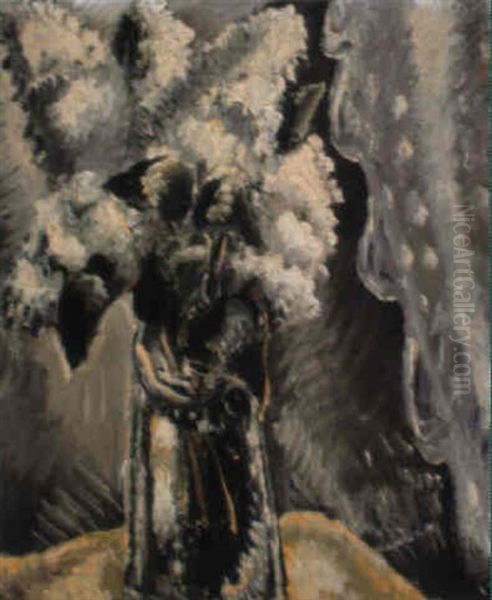

While best known for his figure paintings, Paul Kleinschmidt also dedicated significant attention to still life and landscape genres, applying his characteristic style to these subjects as well. His still lifes often feature arrangements of flowers, fruit, and objects like vases or bottles, rendered with the same vigorous brushwork and rich color palette seen in his figurative work. He imbued these inanimate objects with a sense of weight and presence, exploring textures and the play of light across surfaces.

A notable example is Stilleben mit Seltsamen Vasen (Still Life with Strange Vases), painted around 1931 during a study trip to Cassis in the South of France. This work, later exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago and acquired by the influential collector Erich Cohn, showcases his ability to transform ordinary objects into compelling compositions through expressive handling and vibrant color. The "strangeness" hinted at in the title might refer to the unusual shapes of the vases or the intense, almost animated quality Kleinschmidt imparted to the arrangement.

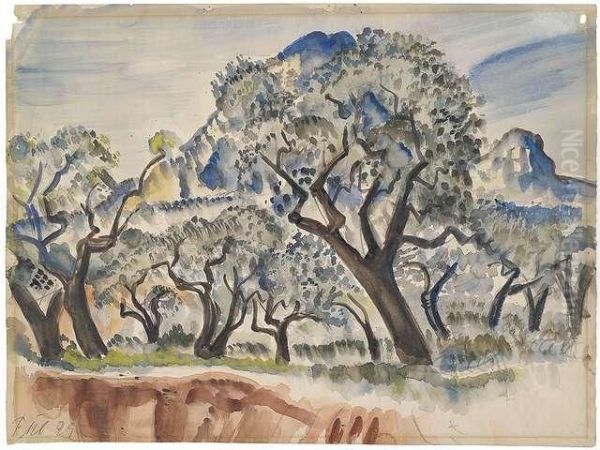

Landscape painting became increasingly important, particularly later in his career. His patron, Erich Cohn, reportedly encouraged him to focus more on landscapes and still lifes, believing these subjects might be more palatable to the American market than his sometimes provocative nudes. However, Kleinschmidt's interest in landscape also seems genuine, offering him a different avenue for exploring color, light, and atmosphere. Works like Landschaft vor Sturm (Landscape before Storm) from 1938, painted during his exile in France, capture the dramatic tension of nature with expressive force. Other works, such as Bridge at Vim or Landschaft in Südfrankreich (Parkausgang), demonstrate his engagement with the light and scenery of Southern Europe, rendered through his distinctively robust and colorful lens.

Patronage and International Recognition: The Role of Erich Cohn

The trajectory of Paul Kleinschmidt's career was significantly shaped by his relationship with the German-American collector Erich Cohn. Cohn, who emigrated from Germany to the United States, became a passionate advocate and crucial supporter of Kleinschmidt's work from the late 1920s onwards. He recognized the artist's unique talent and acquired numerous paintings and graphic works, forming one of the most important collections of Kleinschmidt's art.

Cohn's support extended beyond mere acquisition. He actively promoted Kleinschmidt in the United States, leveraging his connections within the art world. It was likely through Cohn's efforts, or at least with his encouragement, that Kleinschmidt's work was first introduced to American audiences. His paintings were included in the influential "International Exhibition of Paintings" at the Art Institute of Chicago. This exposure was crucial, especially as the political climate in Germany began to darken.

Following this initial introduction, Kleinschmidt was granted a solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1933. This was a significant achievement, marking his arrival on the international stage. Furthermore, his work entered prestigious American museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Cohn's patronage provided not only financial stability during challenging times but also vital international visibility, helping to secure Kleinschmidt's reputation outside of Germany, a factor that became increasingly important as his situation within his homeland deteriorated. The relationship highlights the critical role patrons can play in an artist's career, particularly for those working outside the mainstream or facing adversity.

The Shadow of Nazism: Persecution and Exile

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a catastrophic turning point for modern artists in Germany, including Paul Kleinschmidt. The Nazi regime held deeply conservative and nationalistic views on art, denouncing modernism in all its forms – Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, Dada, New Objectivity – as "degenerate" ("Entartete Kunst"), un-German, Jewish-influenced, or morally corrupting. Kleinschmidt's art, with its bold style and focus on subjects deemed decadent by the Nazis (like nightlife and sensuous nudes), fell squarely into this category.

In 1937, his work was included in the infamous "Entartete Kunst" exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich. This propaganda show aimed to ridicule and defame modern art, displaying confiscated works haphazardly alongside derogatory slogans. Artists featured, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Kleinschmidt himself, faced public humiliation, confiscation of their works from museums, and often professional ruin. Kleinschmidt was subsequently banned from painting and exhibiting in Germany.

Facing persecution and unable to work freely, Kleinschmidt made the difficult decision to leave Germany. He emigrated, spending time first in the Netherlands and later settling in the South of France around 1938. Exile brought its own hardships, including financial instability and isolation. The outbreak of World War II further complicated his situation. As a German national in France, he may have faced periods of internment. Tragically, a significant portion of his life's work stored in Germany was destroyed during Allied bombing raids, an irreplaceable loss. The Nazi era thus inflicted profound personal and professional damage, silencing his public voice in Germany and scattering or destroying much of his artistic output.

Late Works and Post-War Period

Despite the immense difficulties of exile and the war years, Paul Kleinschmidt continued to create art whenever possible. His works from this period, primarily landscapes and still lifes painted in the South of France, retain his characteristic expressive energy but perhaps reflect a different emotional tenor shaped by his experiences. The vibrant light and landscapes of the Mediterranean offered new motifs, which he interpreted through his established stylistic lens.

After the end of World War II, Kleinschmidt was able to return to Germany. He settled in Bensheim, a town in Hesse, near Darmstadt. However, his health had severely deteriorated. He suffered from advanced emphysema, a lung condition likely exacerbated by years of hardship and possibly exposure to materials used in his printmaking processes. His final years were marked by illness, which inevitably impacted his ability to work prolifically.

Nevertheless, he continued to paint when his health permitted. A work like the German Expressionist Oil on Board Still Life Painting dated 1946 indicates his persistence in his artistic practice even in the challenging post-war environment. Paul Kleinschmidt passed away in Bensheim on August 2, 1949, shortly after his 66th birthday. He did not live long enough to fully witness the post-war reassessment and gradual rediscovery of German Expressionism, including his own contributions, which had been suppressed for over a decade.

Artistic Legacy and Historical Assessment

Paul Kleinschmidt occupies a distinct position within the history of 20th-century German art. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as the leading figures of Die Brücke (like Kirchner or Heckel) or Der Blaue Reiter (like Kandinsky or Marc), or socially critical artists like Dix and Grosz, his work offers a unique and powerful contribution to German Expressionism and related movements. His art is characterized by its synthesis of Expressionist intensity, a tangible Realist grounding, and echoes of the clarity found in New Objectivity.

His most enduring legacy lies in his compelling, often monumental depictions of the female form. These works stand out for their sensuousness, vibrant color, and tactile paint application, offering a perspective on the modern woman and urban life that differs from the more angst-ridden or satirical views of some contemporaries. His ability to convey physicality and psychological presence through bold technique remains impressive. His still lifes and landscapes further demonstrate his mastery of color and composition, extending his expressive vision to other genres.

The persecution he suffered under the Nazis and the subsequent loss of much of his work undoubtedly affected his historical visibility. However, thanks in part to the early support of patrons like Erich Cohn and the preservation of works in international collections, his art survived. Post-war exhibitions and ongoing art historical research have helped to re-establish his significance. He is recognized as a powerful individualist within the broader Expressionist movement, an artist who forged a distinctive style to explore themes of sensuality, modern life, and the enduring presence of the physical world, even amidst personal and historical turmoil. His work continues to resonate for its emotional directness and painterly vigor.

Conclusion

Paul Kleinschmidt's life and art encapsulate the dramatic arc of German modernism in the first half of the 20th century. From his academic training and engagement with the Berlin Secession to his mature Expressionist style forged in the crucible of Weimar Berlin, his work reflects both personal vision and historical context. His focus on the sensuous female figure, rendered with bold color and palpable texture, remains his most distinctive contribution. His career, marked by early success, crucial patronage, devastating persecution by the Nazis, exile, and loss, underscores the vulnerability of artists in times of political extremism. Despite these challenges, Kleinschmidt created a body of work that stands as a testament to his unique artistic voice – a voice that blended emotional intensity with a powerful affirmation of the physical world. He remains an important figure for understanding the diversity and depth of German Expressionism.