William Redmore Bigg (1755-1828) stands as a notable figure in British art of the late Georgian period. A painter esteemed for his gentle and often sentimental depictions of rural life, domestic scenes, and the world of children, Bigg carved a niche for himself within the flourishing London art scene. His work, widely disseminated through engravings, captured the prevailing tastes for picturesque and morally uplifting subjects, offering an idealized glimpse into the lives of ordinary people, particularly those in the countryside. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary zeal of some contemporaries, Bigg's consistent output, his engagement with the Royal Academy, and the enduring appeal of his chosen themes ensure his place in the narrative of British art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Felsted, Essex, in 1755, William Redmore Bigg's early life remains somewhat sparsely documented, a common fate for many artists of his era who did not achieve the towering fame of figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds or Thomas Gainsborough. However, it is known that his artistic inclinations led him to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world. In 1778, a pivotal year for the young artist, Bigg was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This institution, founded a decade earlier under the patronage of King George III, was the foremost training ground for aspiring artists in Britain.

At the Royal Academy Schools, students received a rigorous education grounded in the principles of classical art, drawing from antique casts and life models. Bigg's tutelage under Edward Penny (1714-1791) was particularly significant. Penny, one of the founding members of the Royal Academy and its first Professor of Painting, was himself known for his sentimental genre scenes and conversation pieces, often imbued with a moral or charitable message. Works like Penny's The Marquess of Granby Relieving a Sick Soldier (c. 1765) exemplify the kind of subject matter that likely influenced Bigg. Penny's guidance would have provided Bigg with a solid foundation in technique and an appreciation for subjects that resonated with the public's growing interest in scenes of everyday life and virtuous conduct.

The artistic environment of London in the late 1770s and 1780s was rich and varied. While grand manner portraiture, championed by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and the evocative landscapes of Thomas Gainsborough dominated the higher echelons of art, there was also a burgeoning market for genre painting. Artists like Francis Wheatley, known for his "Cries of London" series, and George Morland, whose rustic scenes often depicted a less idealized, more robust vision of country life, were Bigg's contemporaries. This context of a diverse and expanding art market provided opportunities for artists like Bigg to develop their individual styles and thematic preferences.

Rise at the Royal Academy and Professional Development

William Redmore Bigg's association with the Royal Academy was a defining feature of his career. After his initial training, he began to exhibit his works regularly at the Academy's annual exhibitions, a crucial platform for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and sell their paintings. His first exhibit at the Royal Academy was in 1780, and he would continue to show his work there with remarkable consistency until 1827, the year before his death. Over this period, he exhibited a total of 129 paintings, a testament to his productivity and his sustained engagement with the institution.

His talent and dedication did not go unnoticed. In 1787, Bigg was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (A.R.A.), a significant step that acknowledged his growing stature within the artistic community. This was a period when the Academy was still solidifying its influence, with figures like Benjamin West, who would succeed Reynolds as President, playing a prominent role. Full membership as a Royal Academician (R.A.) followed much later, in 1814. This distinction placed him among the elite of British artists, alongside contemporaries such as the portraitist Sir Thomas Lawrence and the visionary painter and poet William Blake, though Blake's relationship with the Academy was often more fraught.

Beyond his painting, some sources indicate that Bigg held positions such as "Engraver to the Duke of York" and "Associate Engraver of the Royal Academy." While primarily known as a painter, these titles suggest an involvement or at least a connection with the world of printmaking, which was vital for the dissemination of an artist's work. The exact nature of these roles in relation to his painting career warrants careful consideration, but it underscores the interconnectedness of painting and engraving in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Artists like John Raphael Smith were both painters and highly successful mezzotint engravers, demonstrating the fluidity between these practices.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

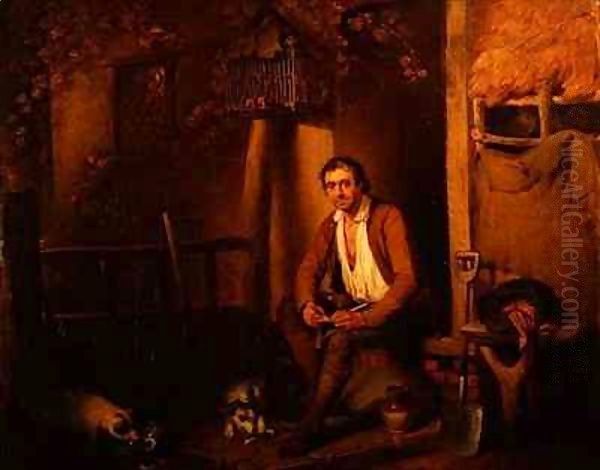

Bigg's artistic style is characterized by its gentle sentimentality, careful attention to detail, and a tendency towards idealized representations, particularly of rural life and childhood. His paintings often convey a sense of warmth, domesticity, and moral virtue, appealing to the sensibilities of a public that appreciated art with a clear narrative and an uplifting message.

A predominant theme in Bigg's oeuvre is the depiction of children. He excelled at capturing the innocence, playfulness, and sometimes the minor tribulations of childhood. These works often carried an educational or moral undertone, reflecting contemporary ideas about child-rearing and the importance of benevolence. His children are typically well-fed, neatly dressed, and engaged in activities that highlight their good nature or the lessons they are learning. This contrasts with the more satirical and socially critical depictions of children found in the work of an artist like William Hogarth from an earlier generation, or the more overtly romanticized and sometimes melancholic children in the "fancy pictures" of Thomas Gainsborough.

Rural life was another cornerstone of Bigg's subject matter. He painted numerous scenes of cottage life, depicting families engaged in simple, virtuous labor or enjoying moments of domestic harmony. These portrayals were often romanticized, presenting an idyllic vision of the countryside that may have glossed over the harsher realities of rural poverty. However, this idealization was common in the art of the period and catered to a largely urban audience that found solace and charm in such pastoral images. Artists like Francis Wheatley and, to some extent, George Morland, also specialized in these rural genre scenes, though Morland's work often had a grittier, more realistic edge.

Charity and benevolence are recurring motifs in Bigg's paintings. He frequently depicted acts of kindness, such as wealthy individuals assisting the less fortunate, or children learning the value of compassion. These themes resonated with the philanthropic spirit of the age and reinforced prevailing social values. The influence of his tutor, Edward Penny, who also favored such subjects, is evident here. The French painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze, whose sentimental and moralizing genre scenes were immensely popular across Europe, also provides a point of comparison for this aspect of Bigg's work.

Bigg's compositions are generally well-ordered, with figures clearly delineated and placed within carefully constructed settings. His use of color is typically harmonious and pleasing, contributing to the overall gentle and appealing quality of his art. While not an innovator in terms of technique or style, Bigg was a skilled craftsman who understood how to create images that were both aesthetically pleasing and emotionally engaging for his audience.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several of William Redmore Bigg's paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations, and many gained wider fame through engraved versions.

_Schoolboys Giving Charity to a Blind Man_ (1778): Exhibited early in his career, this painting exemplifies Bigg's interest in themes of benevolence and childhood virtue. The composition likely depicts well-dressed schoolboys offering assistance to an elderly blind man, a subject designed to evoke sympathy and admiration for the boys' compassionate actions. Such works served a didactic purpose, promoting moral values to the viewing public.

_A Lady and Children Relieving a Cottager_ (1781): This work continues the theme of charity, showcasing a scene where a lady of higher social standing, accompanied by her children, provides aid to a humble cottager. The painting highlights the perceived virtues of the upper classes in caring for the poor, while also presenting an idealized image of social harmony. The inclusion of children learning by example is a typical Bigg touch.

_Black Monday, or The Departure for School_ (1790): This painting, and its companion piece _The Arrival from School, or The Holidays_, captures a universal childhood experience. "Black Monday" refers to the sorrowful return to boarding school after the holidays. Bigg sensitively portrays the mixed emotions of the children – some tearful, others stoic – and the sympathetic concern of their families. The work was engraved by John Jones, significantly broadening its reach. The theme of education and the emotional lives of children were popular, and Bigg's treatment was both relatable and touching. It is suggested that this work may have been inspired by his friendship with a Thomas White.

_The Sailor Boy's Return from a Prosperous Voyage_ (c. 1780s-1837, specific date varies): This painting taps into another popular theme of the era: the life of sailors and the emotional impact of their voyages on their families. The scene depicts a young sailor returning home, presumably with earnings or prizes from his journey, to the joyous welcome of his family. It combines elements of patriotism, familial love, and the romantic allure of the sea, all presented with Bigg's characteristic warmth and sentimentality. Such images resonated strongly in a nation heavily reliant on its navy and maritime trade.

_Cottagers_ (1814): Exhibited in the year he became a full Royal Academician, this work is a mature example of Bigg's idealized rural scenes. It likely portrays a hardworking, virtuous peasant family in a picturesque cottage setting. The emphasis would be on domestic harmony, simple pleasures, and the dignity of labor, appealing to contemporary tastes for the pastoral idyll. The painting was praised for its depiction of industrious rural life.

_Truant Boy_ (also known as _The Truant Boy - Father - Gout_): This subject, often paired with a companion piece showing the boy's return or punishment, deals with childhood mischief and parental authority. The narrative element is strong, and the scene would have been easily understood and appreciated by contemporary audiences. The depiction of the father, sometimes shown suffering from gout (a common ailment often associated with a richer diet and lifestyle, adding a touch of social observation or gentle humor), adds another layer to the domestic drama. John Ward was one of the engravers who reproduced this popular subject.

_The First Grandchild_: This title suggests a tender domestic scene, focusing on intergenerational affection and the joys of family life. Such subjects had wide appeal and allowed Bigg to showcase his skill in portraying gentle emotions and intimate settings.

These works, and many others like them, cemented Bigg's reputation as a painter of charming and morally sound genre scenes. The popularity of engravings after his paintings, by skilled printmakers like John Jones, John Ward, and William Ward (George Morland's brother), ensured that his images reached a far wider audience than those who could afford to buy original oil paintings or visit the Royal Academy exhibitions.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

William Redmore Bigg operated within a vibrant and competitive London art world. His career spanned a period of significant artistic activity, from the heyday of Sir Joshua Reynolds to the rise of Romanticism with painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable.

His closest artistic connection was arguably with George Morland (1763-1804). Bigg was not only a friend of Morland but also his brother-in-law, having married Morland's sister, Maria. While both artists specialized in rural genre scenes, their approaches differed. Morland's work often depicted a more boisterous, sometimes less idealized, and occasionally dissolute side of country life, reflecting his own somewhat chaotic lifestyle. Bigg's scenes, in contrast, were generally more polished, sentimental, and morally upright. Despite these differences, their shared interest in rustic subjects places them within a similar artistic sphere.

Francis Wheatley (1747-1801) was another contemporary known for his sentimental genre scenes, most famously his "Cries of London" series, which depicted street vendors. Like Bigg, Wheatley often painted charming scenes of rural and urban life, appealing to a similar public taste for the picturesque and the anecdotal. Both were elected Royal Academicians and contributed to the popularity of genre painting.

The influence of earlier masters of genre and sentimental scenes, such as Jean-Baptiste Greuze in France, was pervasive. Greuze's moralizing narratives and emotionally charged depictions of family life found echoes in the work of many British artists, including Bigg.

Within the Royal Academy, Bigg would have interacted with a wide range of artists. Benjamin West (1738-1820), the American-born historical painter who succeeded Reynolds as President, and Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), one of the two female founding members, known for her neoclassical and allegorical works, represented different artistic directions but were part of the same institutional framework. Portraitists like Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) and John Hoppner (1758-1810) dominated the lucrative field of society portraiture.

Landscape painting was also undergoing significant development. While Bigg's focus was on figures, the settings of his rural scenes reflect the picturesque aesthetic popular at the time. He would have been aware of the work of landscape specialists like Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759-1817), who also painted rustic figures within his landscapes. Bigg is recorded as having praised the summer sketches of John Constable (1776-1837), indicating an appreciation for emerging talents in landscape art, even if their aims and styles were diverging from his own.

Other genre painters of the period included Henry Walton (1746-1813), whose conversation pieces and domestic scenes share some affinities with Bigg's work, and John Opie (1761-1807), known for his portraits and dramatic genre subjects. The engravers who translated Bigg's paintings into prints were also key figures in the art world. John Jones (c. 1745-1797), John Raphael Smith (1751-1812), John Ward, and William Ward (1766-1826) were highly skilled mezzotint engravers who played a crucial role in popularizing the work of painters like Bigg and Morland.

The satirical prints of Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) and James Gillray (1756-1815) offered a very different, often biting, commentary on contemporary society, providing a stark contrast to the gentler, more idealized visions of artists like Bigg. This diversity highlights the multifaceted nature of the British art scene during Bigg's lifetime.

Later Career, Legacy, and Market Reception

William Redmore Bigg continued to paint and exhibit throughout the early decades of the 19th century. His election as a full Royal Academician in 1814 marked the pinnacle of his official recognition. He remained a consistent contributor to the Royal Academy's exhibitions, demonstrating his enduring commitment to his profession. His subject matter and style remained largely consistent, catering to a public that continued to appreciate his charming and sentimental depictions of domestic and rural life.

He passed away in London on February 6, 1828, reportedly due to ill health. By the time of his death, the artistic landscape was beginning to shift. The Romantic movement was in full swing, with artists like Turner and Constable pushing the boundaries of landscape painting, and a new generation of Victorian artists would soon emerge with different preoccupations.

Bigg's legacy is primarily that of a skilled and appealing genre painter who captured a particular facet of late Georgian sensibility. His work provides valuable insight into the tastes and values of his time, particularly the idealization of childhood, rural simplicity, and benevolent conduct. While he may not be considered a major innovator, his contribution to the tradition of British genre painting is significant. His paintings, and especially the numerous engravings made after them, found their way into many middle-class homes, helping to shape popular perceptions of art and its subjects.

In terms of auction performance, William Redmore Bigg's works appear on the market with moderate frequency. Prices for his original oil paintings can vary depending on size, subject matter, condition, and provenance. For instance, works attributed to his "Circle" or smaller pieces like "A Peep Hole" might fetch prices in the hundreds to low thousands of pounds. More significant or well-documented paintings, such as "The First Grandchild," can achieve higher sums, though generally not reaching the levels of his most famous contemporaries like Gainsborough or Reynolds. The market for engravings after his work is also active, with these prints often being more accessible to collectors.

His paintings are held in various public and private collections. Exhibitions focusing on British art of the 18th and 19th centuries, or on themes of childhood and rural life, occasionally feature his work. For example, an exhibition at the Horsham Museum and Art Gallery titled "Portraying the Poor and Industrious in the Age of Waterloo" included his work, highlighting his romanticized depictions of these social groups.

Conclusion

William Redmore Bigg was an artist who successfully navigated the London art world of his time, achieving recognition from the Royal Academy and popularity with the public. His paintings of children, cottage life, and scenes of charity and domesticity struck a chord with contemporary audiences, offering charming, sentimental, and morally uplifting visions. Educated at the Royal Academy Schools under Edward Penny, he absorbed the prevailing tastes for genre subjects and developed a distinctive style characterized by its gentle appeal and careful execution.

Through his numerous exhibits at the Royal Academy and the widespread dissemination of his work via engravings by prominent printmakers, Bigg became a familiar name. He contributed to a visual culture that valued the picturesque, the anecdotal, and the virtuous. While the grand narratives of history painting or the innovations of landscape art might have captured more critical attention, Bigg's focus on the more intimate and relatable aspects of human experience ensured his enduring, if modest, place in British art history. He remains a significant representative of a particular strand of Georgian genre painting, a chronicler of an idealized world that continues to hold a certain nostalgic charm.