Piet Mondrian stands as a colossus in the annals of twentieth-century art. A Dutch painter whose career traced a remarkable trajectory from traditional representation to radical abstraction, Mondrian became synonymous with a specific, rigorous form of geometric art known as Neoplasticism. As a leading figure in the De Stijl movement, his work and theories profoundly shaped not only modern painting but also architecture, design, and typography, leaving an indelible mark on the visual culture of modernity. His quest for universal harmony through pure form and color continues to resonate, making him one of the most influential artists of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

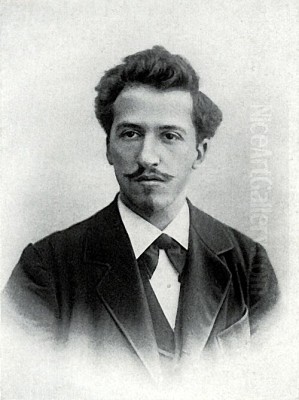

Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan, later known as Piet Mondrian, was born on March 7, 1872, in Amersfoort, Utrecht, in the Netherlands. His upbringing was steeped in a strict Calvinist tradition. His father, Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan Sr., was a qualified drawing teacher and the headmaster of a local primary school. This early exposure to art was further nurtured by his uncle, Frits Mondriaan, a professional painter associated with the Hague School style of landscape painting. These familial influences provided Mondrian with his initial artistic instruction and undoubtedly sparked his lifelong dedication to painting.

Despite the religious conservatism of his household, Mondrian's artistic inclinations were encouraged. He initially pursued qualifications to become a teacher himself. In 1889, he earned his diploma to teach primary school drawing, followed in 1892 by a qualification for secondary school drawing. This path, however practical, was secondary to his ambition to become a serious artist. He moved to Amsterdam to enroll at the prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Fine Arts), where he studied from 1892 to 1897.

During his time at the Academy and in the years immediately following, Mondrian's work was largely conventional. He honed his skills through traditional methods, including drawing from models, copying Old Masters, and painting landscapes. His early output reflects the prevailing styles in the Netherlands at the time, particularly the tonal naturalism of the Hague School and the burgeoning influence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He painted numerous landscapes around Amsterdam and Domburg, often depicting windmills, fields, and rivers in a sensitive, observant manner.

The Path Towards Abstraction

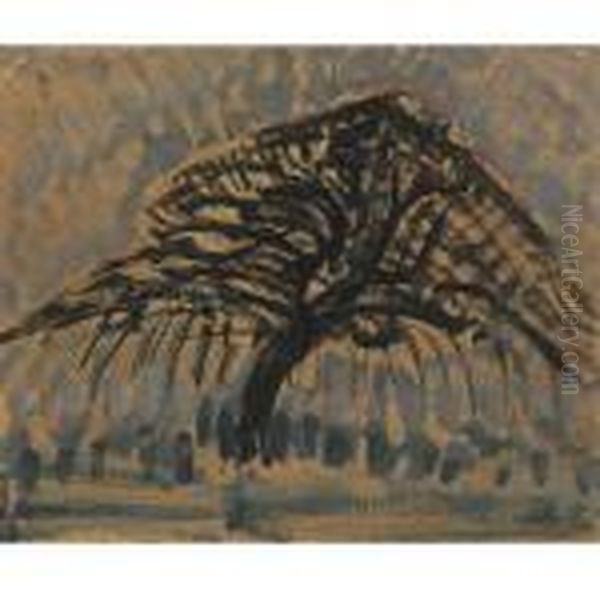

The first decade of the twentieth century marked a period of significant transition for Mondrian. Influenced by artists like Jan Toorop and the broader Symbolist movement, as well as the expressive color use of Fauvism, his work began to shed its purely naturalistic skin. He started experimenting with bolder colors and more simplified forms, moving away from detailed representation towards capturing the essential structure and spiritual essence of his subjects, particularly trees and church facades.

This period, roughly from 1907 to 1911, can be seen as his Expressionist and Symbolist phase. Works like "The Red Tree" (1908-1910) and the "Evolution" triptych (1911) showcase this shift. Color became less descriptive and more symbolic or emotive, and forms were increasingly stylized. He was also deeply interested in Theosophy, a spiritual movement founded by Helena Blavatsky, which sought underlying universal truths and spiritual realities behind the visible world. This philosophical leaning would profoundly inform his later abstract work, fueling his quest for harmony and order.

The changing artistic landscape, including the rise of photography which challenged painting's role in realistic depiction, and the increasing pace of industrialization, likely contributed to Mondrian's search for a new artistic language. He sought an art form that could express deeper, more universal truths beyond mere surface appearance. His focus gradually shifted from the specific details of nature to its underlying structures and rhythms.

Parisian Encounters and Cubist Influence

A pivotal moment in Mondrian's career came in late 1911 or early 1912 when he moved to Paris, the vibrant heart of the European avant-garde. It was here that he encountered Cubism firsthand, particularly the works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. This encounter was transformative. He saw in Cubism a method for breaking down objects into their geometric components and analyzing structure, which resonated deeply with his own evolving artistic goals.

Absorbing the lessons of Cubism, Mondrian began to radically simplify his compositions. His paintings from 1912 to 1914, often featuring trees, building facades, or scaffoldings, show a progressive flattening of space, a muted palette of ochres, grays, and browns, and an increasing emphasis on intersecting horizontal and vertical lines. Works like the "Trees" series and "Composition in Oval" paintings demonstrate his systematic deconstruction of representational forms into near-abstract linear structures.

It was during this initial Paris period, around 1912, that he also modified his name, dropping the second 'a' from 'Mondriaan' to become 'Mondrian'. This change is often interpreted as a symbolic break from his Dutch origins and an embrace of the international avant-garde centered in Paris. While deeply influenced by Cubism, Mondrian felt it did not go far enough in its abstraction; he sought to push beyond the fragmented representation of objects towards a purely non-representational art.

The Birth of De Stijl and Neoplasticism

The outbreak of World War I forced Mondrian to return to the Netherlands in 1914, where he remained for the duration of the conflict. This period proved unexpectedly fruitful. Isolated from Paris, he came into contact with other Dutch artists who shared his desire for a radically new art form reflecting modern life and universal principles. Key among these were Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck.

Van der Leck's use of flat planes of primary color had a significant impact on Mondrian, encouraging him to move away from the muted Cubist palette towards pure hues. Discussions with Van Doesburg, a painter, writer, and theorist, were crucial in crystallizing their shared ideas. Together, in 1917, they founded the De Stijl (The Style) movement and its eponymous journal. Other artists and architects associated with the group included Vilmos Huszár, Georges Vantongerloo, and the architect Gerrit Rietveld.

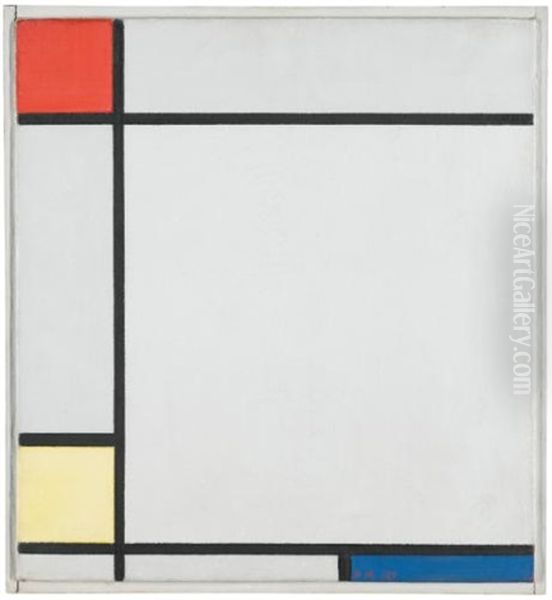

Within the pages of De Stijl, Mondrian articulated his artistic philosophy, which he termed "Nieuwe Beelding," translated as Neoplasticism (or "New Plastic Art"). This theory advocated for a pure form of abstraction based on the reduction of form to straight horizontal and vertical lines and the restriction of color to the three primary colors (red, yellow, blue) plus the three primary non-colors (white, black, gray). Mondrian believed these fundamental elements represented universal forces and could create a visual language of perfect harmony and balance, reflecting underlying spiritual truths.

The Mature Neoplastic Style

Returning to Paris after the war in 1919, Mondrian entered the most iconic phase of his career. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he rigorously developed and refined his Neoplastic principles. His paintings became characterized by grids of black horizontal and vertical lines of varying thickness, intersecting at right angles, creating asymmetrical arrangements of rectangular planes. Some of these planes were filled with flat, unmodulated primary colors, while others remained white or gray.

Works such as Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue (1930) and Composition No. III, with Red, Blue, Yellow and Black (1927) exemplify this mature style. Each element was carefully placed to achieve a dynamic equilibrium, a state of harmony arising from the tension between opposing forces (horizontal vs. vertical, color vs. non-color). Mondrian saw this abstract harmony as a universal principle applicable not just to painting but to life itself, envisioning a future where Neoplastic principles would inform architecture and design, creating harmonious environments for modern society.

His studio in Paris itself became a three-dimensional embodiment of his Neoplastic ideas, with walls and furniture arranged and colored according to his principles. He believed art's role was not merely decorative but spiritual and societal, aiming to reveal the underlying order of the universe and pave the way for a more balanced human existence. His philosophical explorations, influenced by Theosophy and thinkers like Spinoza, continued to underpin his artistic practice, viewing his geometric abstractions as expressions of objective, universal reality rather than subjective emotion.

Life Between the Wars: Paris and London

Mondrian remained based in Paris for much of the interwar period, becoming a respected, if somewhat isolated, figure in the avant-garde. He exhibited regularly and continued to refine his Neoplastic compositions, experimenting with diamond-shaped canvases (lozenge compositions) and variations in line thickness and color placement. His commitment to pure abstraction remained unwavering, even as other movements like Surrealism gained prominence.

The rise of Nazism in Germany cast a shadow over the European avant-garde. Mondrian's work, like that of many modern artists, was deemed "degenerate" by the Nazi regime. Two of his paintings were included in the infamous "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art) exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich in 1937, intended to ridicule modern art. As the political situation in Europe deteriorated and the threat of war loomed, Mondrian left Paris in September 1938 for London.

His time in London was relatively brief, lasting about two years. He continued to work, connecting with British artists like Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth who shared his interest in abstraction. However, the Blitz, the German bombing campaign against London that began in September 1940, made life there increasingly dangerous. Seeking safety and perhaps sensing new artistic possibilities, Mondrian made the decision to emigrate to the United States.

The New York Years: Final Flourish

In October 1940, Piet Mondrian arrived in New York City. He was nearly seventy years old, but the move invigorated him. He was captivated by the energy, architecture, and particularly the jazz music (especially Boogie Woogie) of the American metropolis. This new environment infused his final works with an unprecedented dynamism and complexity.

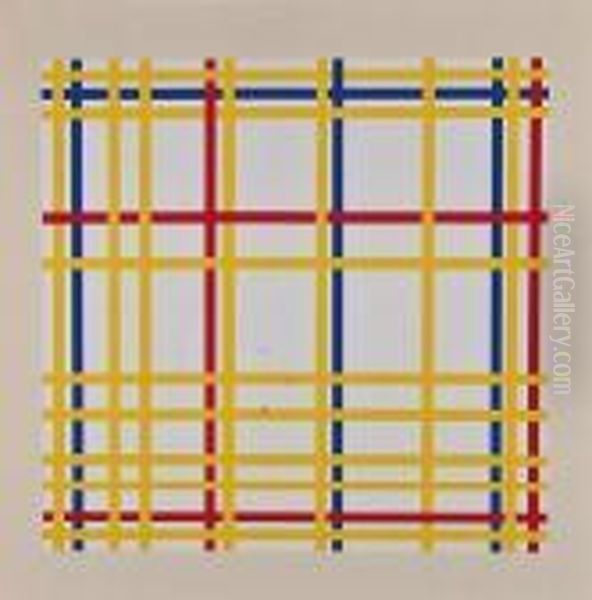

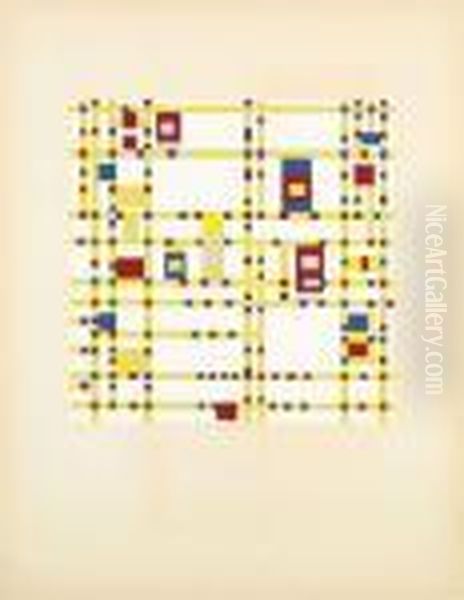

His late New York paintings marked a departure from the austere black grids of his Paris years. He began using colored lines, often made from small pieces of colored tape that he could easily reposition, creating intricate, pulsating rhythms. The black lines disappeared, replaced by vibrant grids of yellow, red, and blue. Works like New York City I (1942) and the celebrated Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43) exemplify this final phase. They retain the Neoplastic principles of horizontal and vertical lines and primary colors but express a new sense of movement, rhythm, and optical vibrancy, reflecting the bustling life and syncopated beats of his adopted city.

Broadway Boogie Woogie, his last completed masterpiece, is a dazzling composition of small, interlocking squares and rectangles of color along yellow lines, suggesting the city's grid, flashing lights, and the improvisational energy of jazz. It represents the culmination of his lifelong quest for dynamic equilibrium, achieved here with a newfound exuberance. Mondrian died of pneumonia in New York City on February 1, 1944, at the age of 71, still actively engaged in his artistic exploration.

Interactions with Contemporaries

Mondrian's career was shaped by interactions with numerous artists and thinkers. His early development was influenced by Dutch contemporaries like Jan Toorop and the legacy of Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Symbolists. The encounter with Cubism in Paris brought the influence of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque to the fore, providing a crucial stepping stone towards abstraction, even as he sought to move beyond their approach. Paul Cézanne's structural analysis of form can also be seen as a precursor influence.

His most significant collaborations occurred within the De Stijl movement. The intellectual partnership with Theo van Doesburg was foundational, leading to the creation of the journal and the codification of Neoplasticism. Bart van der Leck's bold use of primary colors directly impacted Mondrian's palette. While united by shared ideals, interactions among De Stijl members (including Vilmos Huszár, Georges Vantongerloo, Gerrit Rietveld) were often conducted more through correspondence and publications than frequent face-to-face meetings, partly due to geographical dispersion, especially during the war years. Mondrian eventually distanced himself from Van Doesburg in the mid-1920s over theoretical disagreements, particularly Van Doesburg's introduction of diagonal lines (Elementarism), which Mondrian felt compromised the universal stability of the horizontal and vertical.

In London, he found kinship with British abstractionists Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. In New York, he became part of a community of European émigré artists and interacted with American artists, although he remained primarily focused on his own rigorous path. His work, in turn, would profoundly influence subsequent generations.

Artistic Legacy and Enduring Influence

Piet Mondrian's legacy is immense and multifaceted. He is universally recognized as a pioneer of abstract art, whose Neoplastic style represents one of the most radical and influential developments of modernism. His reduction of painting to its essential elements—straight lines, right angles, primary colors—created a visual language that aimed for universality and timeless harmony.

His influence extended far beyond the canvas. The principles of De Stijl and Neoplasticism had a profound impact on twentieth-century architecture and design. The clean lines, geometric forms, and functional aesthetics promoted by the Bauhaus school in Germany, under figures like Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, owe a debt to De Stijl's vision of integrating art and life. Gerrit Rietveld's Schröder House in Utrecht is a prime architectural example of De Stijl principles in practice.

In graphic design and typography, the asymmetrical layouts, sans-serif fonts, and use of grids popularized by De Stijl became hallmarks of modern design. Mondrian's iconic style has also permeated popular culture, famously inspiring Yves Saint Laurent's "Mondrian" dresses in 1965 and continuing to appear in various forms of fashion, advertising, and product design.

Furthermore, Mondrian's rigorous abstraction paved the way for later art movements, including Minimalism in the 1960s. Artists like Donald Judd, Frank Stella, and Ellsworth Kelly explored geometry, color, and non-representational forms in ways that echo Mondrian's pursuit of purity and objectivity, even as they developed their own distinct aesthetics. His work continues to be studied and admired for its formal purity, conceptual rigor, and underlying spiritual quest.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Scholarly Perspectives

Despite his austere art, Mondrian's life contained complexities and attracted various interpretations. Rumors regarding his personal life, including unsubstantiated speculation about his sexuality during his Amsterdam years, surfaced in biographical accounts, reflecting perhaps the societal pressures of the time or attempts to understand his intense dedication to his art. His decision to change the spelling of his name remains a point of minor discussion—a break with tradition or an alignment with internationalism.

His relationship with his father was reportedly complex, marked by differing views on art, with his father favoring traditionalism while Mondrian pursued the avant-garde. Mondrian himself was known to be intensely private about his personal life, leading to limited concrete information about his relationships.

Controversy also touched his art directly. Early abstract works, like a piece possibly titled Edge of the Forest (1913), faced ridicule from critics unprepared for such radical departures from representation. The inclusion of his work in the Nazi "Degenerate Art" exhibition was a politically charged condemnation. More recently, a peculiar discovery revealed that his painting New York City I had likely been displayed upside down for decades in various museums, a testament to the potential for misinterpretation even with seemingly straightforward abstract works.

Scholarly debate continues regarding the precise influence of Theosophy and philosophy (like Spinoza or Heraclitus) on his art—was it a direct source or a parallel interest? Some interpretations view his work through a socio-political lens, seeing his quest for harmony as an implicit critique of the chaos and materialism of capitalist society. Biographies, such as the one by his friend Michel Seuphor, have been analyzed for potential subjectivity in shaping the artist's image. The relationship between Mondrian's extensive theoretical writings and his actual paintings—whether the practice perfectly embodied the theory—also remains a subject of art historical discussion.

Conclusion

Piet Mondrian's journey from a skilled landscape painter to the creator of a radically pure abstract language marks him as a pivotal figure in modern art history. Through Neoplasticism and his central role in De Stijl, he sought to distill the visual world into fundamental elements of line and primary color, striving for a universal harmony that he believed reflected underlying spiritual truths and could provide a blueprint for a better modern world. His iconic grid compositions, instantly recognizable and endlessly influential, transcended painting to shape architecture, design, and visual culture at large. While scholarly debates continue about the nuances of his philosophy and influences, his status as a master of abstraction and a visionary whose work embodies the rational spirit and utopian aspirations of early modernism remains undisputed. His legacy endures in the clean lines and balanced forms that continue to inform aesthetics today.