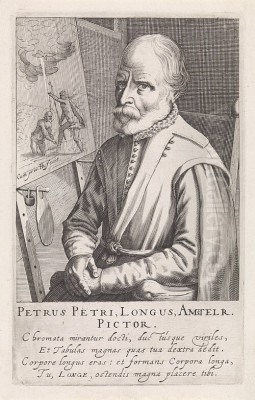

Introduction: The Life and Times of "Long Peter"

Pieter Aertsen, born in Amsterdam around 1508 and active until his death there in 1575, stands as a pivotal figure in the Northern Renaissance. Affectionately nicknamed "Lange Pier" or "Long Peter" owing to his notable height, Aertsen carved a unique niche for himself as a master painter of both genre scenes and still life, often ingeniously blending the two. His career unfolded during a period of profound religious and social transformation in the Netherlands, straddling the artistic worlds of Amsterdam and the vibrant commercial hub of Antwerp. Aertsen is celebrated not merely for his technical skill but for his groundbreaking approach to subject matter, elevating scenes of everyday life – markets, kitchens, peasant festivities – to a monumental scale previously reserved for historical or religious narratives. His work provides a fascinating window into sixteenth-century Dutch life while simultaneously laying the groundwork for major developments in Flemish and Dutch art in the centuries that followed.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Amsterdam

Pieter Aertsen's artistic journey began in his native Amsterdam. While details of his earliest years remain somewhat scarce, it is widely accepted that he received his initial training under Allaert Claesz., a respected Amsterdam painter. This apprenticeship likely occurred in the 1520s. Claesz.'s own work, though not extensively surviving, is thought to have included competent religious scenes and possibly portraits. Training under Claesz. would have provided Aertsen with a solid foundation in the prevailing artistic techniques and conventions of the Northern Renaissance, including oil painting techniques, composition, and drawing.

Amsterdam in the early sixteenth century was a growing city, though not yet the dominant metropolis it would become in the Golden Age. The artistic environment would have been influenced by earlier Dutch masters and the broader currents of the Northern Renaissance, which emphasized detailed realism and often carried underlying moral or religious messages. This early exposure to the craft in Amsterdam shaped Aertsen's fundamental skills, preparing him for the next significant phase of his career in the more dynamic artistic center of Antwerp. His training likely instilled in him the meticulous attention to detail that would become a hallmark of his later, more innovative works.

The Antwerp Years: A Crucible of Innovation

Around 1535, seeking broader opportunities and exposure, Pieter Aertsen relocated to Antwerp. This city was then the economic powerhouse of the Low Countries and arguably the most important artistic center north of the Alps. Its bustling international trade fostered a wealthy merchant class eager to patronize the arts, creating a competitive and stimulating environment for painters. In the same year he arrived, or shortly thereafter, Aertsen was admitted as a master into the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke, the city's official organization for painters and other artisans. Membership was crucial for establishing an independent workshop and accepting commissions.

During his time in Antwerp, which lasted over two decades until about 1556, Aertsen's artistic identity truly coalesced. He absorbed the influences of the Antwerp school, which included established figures like Quentin Matsys, whose work blended late Gothic traditions with Renaissance innovations, and contemporaries such as Jan Sanders van Hemessen, known for his robust figures and genre scenes often imbued with moralizing undertones. Aertsen initially continued to paint religious subjects, including altarpieces, but it was in Antwerp that he began experimenting with the compositional formats that would define his legacy. The city's vibrant markets and prosperous households provided ample inspiration for his burgeoning interest in depicting everyday life and material abundance.

The Birth of the Monumental Genre Scene

It was during his prolific Antwerp period that Pieter Aertsen pioneered what art historians often term the "monumental genre scene" or "inverted still life." This innovative format represented a radical departure from traditional hierarchies of subject matter. In these works, Aertsen placed large, meticulously rendered still-life elements – heaps of vegetables, cuts of meat, arrays of bread, kitchen utensils – or bustling scenes of market vendors and kitchen maids in the immediate foreground, dominating the composition.

The traditional main subject, often a biblical narrative like Christ visiting Mary and Martha, the Flight into Egypt, or Christ and the Adulteress, was relegated to a smaller scale in the background, visible through a doorway or window, or subtly integrated into the larger scene. This "inversion" challenged viewers, forcing them to engage with the mundane, material world upfront before, or perhaps while, contemplating the spiritual message embedded within. This approach reflected a growing interest in secular subjects among patrons, yet Aertsen skillfully retained a moral or religious dimension, often creating a deliberate contrast between worldly abundance or temptation (foreground) and spiritual values (background). His style during this period also showed affinities with Northern Mannerism, seen in elongated figures, dynamic, sometimes crowded compositions, and a sophisticated handling of space.

Masterworks: A Closer Look – The Meat Stall

Perhaps Pieter Aertsen's most famous and analyzed work is The Meat Stall, also known as Butcher's Stall, painted in 1551 and now housed in the Gustavianum, Uppsala University. This large panel is a quintessential example of his innovative style. The foreground is overwhelmingly dominated by a lavish, almost overwhelming display of meat – sausages, poultry, hams, a pig's head, cuts of beef – alongside fish, pretzels, butter, and cheese. The sheer abundance and detailed rendering of the foodstuffs are remarkable, showcasing Aertsen's skill as a still-life painter.

Amidst this scene of earthly plenty, several narrative and symbolic elements unfold. In the background, visible through the stall opening, the Holy Family (Joseph, Mary riding a donkey, and the infant Jesus) is depicted during their Flight into Egypt, distributing alms to the poor. This juxtaposition creates a stark contrast between carnal indulgence and spiritual nourishment, charity, and humility. Further symbolic details enrich the painting: crossed fish on a pewter plate may allude to Lent or Christ himself, oysters and mussels on the ground were sometimes associated with lust, and a sign hanging on the right advertises land for sale, possibly referencing contemporary social issues. The painting functions as both a celebration of Antwerp's prosperity and a complex moral allegory, warning against gluttony and worldliness while reminding viewers of spiritual duties.

Masterworks: Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Another signature theme for Aertsen was the biblical story of Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (Luke 10:38-42), which he painted multiple times with variations (versions exist in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, among others). These paintings perfectly encapsulate his "inverted" compositional strategy. Typically, the foreground is dominated by a busy kitchen scene. Martha, embodying the vita activa (active life), is shown energetically preparing food, surrounded by an abundance of realistically depicted kitchenware, vegetables, and other provisions.

Through an opening or in a rear chamber, Christ is seated, conversing with Mary, who sits attentively at his feet, representing the vita contemplativa (contemplative life). Christ's gentle rebuke of Martha for being "worried and upset about many things" while Mary has "chosen what is better" provides the moral core. Aertsen uses the detailed foreground not just for visual appeal but to underscore the narrative's theme: the potential distraction of worldly cares (represented by the elaborate meal preparation) from spiritual focus. The sheer visual weight given to the kitchen activities forces the viewer to confront this tension directly. The paintings are masterclasses in rendering textures – metal pots, earthenware jugs, woven baskets, various foods – demonstrating Aertsen's observational prowess.

Masterworks: Market Scenes and Everyday Commerce

Aertsen frequently turned his attention to bustling market scenes, often integrating biblical narratives subtly within the vibrant depiction of commerce. A notable example is the Market Scene with Christ and the Adulteress (c. 1550-1559, Städel Museum, Frankfurt). Here, a lively market square is filled with vendors selling poultry, eggs, cheese, and vegetables. Peasants and townspeople engage in trade and conversation. The foreground is rich with still-life details, capturing the textures and forms of the goods on display.

Almost hidden within this panorama of daily life, in the middle ground, is the biblical episode of Christ challenging the accusers of the woman taken in adultery (John 8:1-11). By placing this significant religious event within the context of ordinary market activity, Aertsen again juxtaposes the sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the material. These market scenes allowed him to explore complex compositions with numerous figures and a wealth of anecdotal detail, reflecting the energy and diversity of urban life in the sixteenth-century Netherlands. They also served the growing demand from middle-class patrons for art that depicted familiar environments, while still retaining layers of meaning.

Masterworks: Peasant Scenes and Festivities

Beyond kitchen and market scenes, Aertsen also contributed to the burgeoning genre of peasant painting, a field famously developed by his slightly younger contemporary, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. While Bruegel often focused on panoramic views of peasant life, often with a satirical or anthropological eye, Aertsen's peasant scenes tend to be more focused, sometimes depicting indoor festivities or specific activities. A well-known example is The Egg Dance (1552, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

The Egg Dance portrays a tavern interior where a young man attempts the popular challenge of dancing among eggs scattered on the floor without breaking them, likely a Lenten custom or a game associated with spring festivals. The scene is filled with lively figures drinking, talking, and observing the dancer. While capturing the boisterous energy of peasant life, the painting may also carry moralizing undertones, perhaps warning against excessive revelry or foolish behavior, themes common in genre painting of the era. Aertsen's depiction is robust and earthy, emphasizing the physicality of the figures and the details of their surroundings, distinguishing his approach from the more detached viewpoint sometimes found in Bruegel's work. These paintings further demonstrate Aertsen's versatility and his role in broadening the acceptable range of subjects for serious art.

Return to Amsterdam and Later Career

Around 1556, after more than twenty successful years in Antwerp, Pieter Aertsen decided to return to his native Amsterdam. The reasons for this move are not definitively documented but may have involved family ties, patronage opportunities, or perhaps a desire to return to his roots as he entered his later career phase. Amsterdam was growing in importance, and while Antwerp remained a major center, the northern Netherlands was beginning to assert its own cultural identity, particularly as religious and political tensions escalated.

Back in Amsterdam, Aertsen continued to be a highly respected and productive artist. He received significant commissions, including prestigious projects for altarpieces in Amsterdam's main churches, the Oude Kerk (Old Church) and the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church). These large-scale religious works, unfortunately, did not survive the waves of iconoclasm that swept through the Netherlands. Despite this loss, his reputation remained high. He also continued to produce the market and kitchen scenes that had brought him fame, adapting his style perhaps slightly to suit the tastes of Amsterdam patrons. His workshop remained active, and significantly, his artistic legacy was carried on by his sons, Pieter Pietersz. the Elder, Aert Pietersz., and Dirck Pietersz., who all became painters in their own right, working in styles influenced by their father.

Art Amidst Turmoil: The Iconoclasm and its Aftermath

Pieter Aertsen lived and worked through one of the most turbulent periods in Netherlandish history: the Reformation and the subsequent religious conflicts that led to the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule. A critical event during his later career was the Beeldenstorm, or Iconoclastic Fury, which erupted violently in 1566, particularly affecting Antwerp, and continued sporadically elsewhere. Protestant mobs, angered by what they saw as idolatry in Catholic churches, destroyed vast quantities of religious art – statues, stained glass, and altarpieces.

This widespread destruction had a profound impact on artists like Aertsen who relied on church commissions. Many of his own altarpieces, including those he created after returning to Amsterdam, were lost during these events or in subsequent waves of reform. While devastating for the preservation of his religious oeuvre, the iconoclasm inadvertently may have reinforced the shift in patronage towards secular subjects. Wealthy merchants and citizens increasingly commissioned paintings for their homes, favoring portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, and still lifes – precisely the areas where Aertsen had already proven himself an innovator. His market and kitchen scenes, with their blend of realism, abundance, and subtle moralizing, were perfectly suited to this changing market, allowing his career to continue thriving despite the religious upheaval. He died in 1575, just before the situation in the northern Netherlands stabilized further towards Protestant dominance but having witnessed the dramatic transformation of its artistic landscape.

Aertsen's Artistic Circle: Collaboration and Competition

Throughout his career, Pieter Aertsen operated within a dynamic network of artists. His most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with his nephew and pupil, Joachim Beuckelaer (c. 1533–c. 1575). Beuckelaer worked closely with Aertsen, particularly during the Antwerp years, and adopted his master's innovative style of monumental market and kitchen scenes. While Beuckelaer developed his own variations, often featuring even more densely packed compositions and brighter colors, the thematic and compositional debt to Aertsen is clear. Their works were sometimes so similar that attribution can be challenging, suggesting a close workshop collaboration or at least a shared exploration of popular themes.

Aertsen also interacted with and responded to other leading artists of his time. His work shows an awareness of, though a stylistic divergence from, the peasant scenes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. While both depicted everyday life, Aertsen's focus was often tighter, more centered on objects and interior spaces, compared to Bruegel's broader, narrative landscapes. In Antwerp, he would have been aware of the work of prominent history painters like Frans Floris, who represented a more Italianate Mannerist style. He also competed in the art market with contemporaries like Jan Sanders van Hemessen and later, perhaps indirectly, with artists like Maerten de Vos. His own sons, particularly Pieter Pietersz. the Elder, continued his genre painting tradition in Amsterdam, ensuring the family's artistic presence into the next generation.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Pieter Aertsen's impact on the history of European art was substantial and multifaceted. His primary contribution lies in his pioneering role in the development of still life and genre painting as independent or semi-independent subjects. By giving unprecedented prominence to everyday objects and scenes, he fundamentally altered traditional artistic hierarchies and paved the way for the flourishing of these genres in the Dutch Golden Age and Flemish Baroque periods.

His influence was immediate and direct on his pupil Joachim Beuckelaer, who further popularized the market and kitchen scene. His sons also carried forward elements of his style. More broadly, Aertsen's detailed realism in depicting food and objects profoundly influenced later still-life specialists in both the northern and southern Netherlands, such as the Dutch masters Pieter Claesz. and Willem Claeszoon Heda, and the Flemish painters Frans Snyders and Jacob Jordaens, who often incorporated lavish still-life elements into their larger compositions.

Furthermore, Aertsen's innovations resonated beyond the Low Countries. His works were known and admired in Italy, where they are believed to have influenced painters like Vincenzo Campi and Bartolomeo Passerotti in the late sixteenth century, who also created market scenes and depictions of food vendors. Some scholars even suggest a possible influence on the early work of Annibale Carracci, particularly his genre paintings like The Butcher's Shop. Aertsen's bold compositions and his elevation of the mundane demonstrated new possibilities for painting that resonated across Europe.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Worlds

Pieter Aertsen occupies a crucial position in the narrative of Northern European art. He was an artist of transition, skillfully navigating the complex cultural landscape of the sixteenth century. His work forms a bridge between the late Gothic tradition and the emerging sensibilities of the Baroque, and between the dominance of religious art and the rise of secular genres. By ingeniously combining depictions of everyday life and material abundance with underlying spiritual or moral themes, he catered to the changing tastes of his time while creating works of enduring visual power and complexity.

His development of the monumental genre scene and his mastery of still-life painting were groundbreaking innovations that profoundly shaped the future course of art in the Netherlands and beyond. Despite the tragic loss of many of his religious works to iconoclasm, the surviving paintings, particularly his iconic market and kitchen scenes like The Meat Stall and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, secure his legacy as a bold innovator and a keen observer of the world around him. "Long Peter" Aertsen was more than just a painter of markets and kitchens; he was a key figure who helped redefine the very subjects and purposes of painting in the Northern Renaissance.