Pieter Binoit (circa 1590–1632) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the development of still life painting in early 17th-century Germany. Active primarily in Cologne, Frankfurt am Main, and Hanau, Binoit emerged during a period of profound artistic and cultural transition, where the detailed naturalism of the Renaissance was evolving into the dynamic drama of the Baroque. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant coloration, and often complex, symbolic arrangements, offers a fascinating window into the aesthetic sensibilities and intellectual currents of his time. As a painter of flowers, fruits, and banquet pieces, Binoit contributed to a genre that was rapidly gaining popularity across Europe, reflecting new scientific interests, burgeoning global trade, and a wealthy bourgeoisie eager to adorn their homes with images of earthly abundance and contemplative beauty.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Pieter Binoit was born in Cologne around 1590. His family background was rooted in the Protestant faith; his father was a Huguenot refugee who had fled from Tournai in the Southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium) due to religious persecution. This familial experience of displacement and religious conviction likely shaped the young Binoit's worldview, in an era marked by intense religious conflicts across Europe, culminating in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) which would ravage much of Germany during his lifetime.

Binoit received his artistic training in Hanau, a town near Frankfurt am Main that had become a refuge for Protestant immigrants, particularly from the Netherlands. He was a pupil of Daniel Soreau (c. 1560–1619), a Walloon still-life painter who had also sought refuge in Germany and established a prominent workshop in Hanau. Soreau himself was a significant figure in the Frankenthal School tradition, known for its detailed and naturalistic depictions. Under Soreau's tutelage, Binoit would have learned the meticulous techniques required for still life painting, including the precise rendering of textures, the careful observation of light and shadow, and the art of composition. Daniel Soreau's sons, Isaak Soreau (1604-1644) and Peter Soreau (active c. 1620-1640), were also active as still-life painters in this circle, continuing their father's legacy.

The artistic environment in Hanau and nearby Frankfurt was vibrant. Frankfurt, a major trading hub, provided access to exotic goods, flowers, and fruits that became the subjects of still life paintings. This environment fostered a keen interest in the natural world, aligning with broader European trends of scientific inquiry and collection. Binoit's education would have emphasized direct observation, a hallmark of the burgeoning empirical spirit of the age.

The Artistic Milieu: Frankfurt, Hanau, and the Rise of Still Life

The early 17th century witnessed the flourishing of still life painting as an independent genre. Previously, depictions of inanimate objects were often relegated to secondary elements within larger religious or mythological scenes. However, artists like Binoit began to focus exclusively on arrangements of flowers, fruits, tableware, and other objects, imbuing them with both aesthetic appeal and symbolic meaning.

Frankfurt am Main and Hanau were important centers for this development in Germany. The influence of Netherlandish painters was particularly strong, due to the influx of artists fleeing religious strife and seeking new patronage. Georg Flegel (1566–1638), active in Frankfurt, is considered one of the pioneers of German still life painting. His meticulously detailed and often intimate compositions, featuring everyday objects, food, and flowers, would have been known to Binoit and likely served as an important local precedent. Flegel's work, like that of Binoit, often carried subtle symbolic undertones, reflecting on themes of transience and the bounty of nature.

The broader European context also played a role. In the Netherlands, artists such as Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621) and his sons, along with his brother-in-law Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657), were creating exquisite flower paintings characterized by their jewel-like precision and encyclopedic depiction of different species. In Antwerp, Osias Beert the Elder (c. 1580–1623/24) and Clara Peeters (1594–c. 1657) were producing opulent banquet pieces and flower still lifes. While Binoit developed his own distinct style, he was undoubtedly aware of these broader trends, which were disseminated through prints, travel, and the movement of artists and artworks. The demand for such paintings came from a growing middle class and aristocracy who appreciated their decorative qualities and the intellectual engagement they offered through symbolism.

Characteristics of Binoit's Style

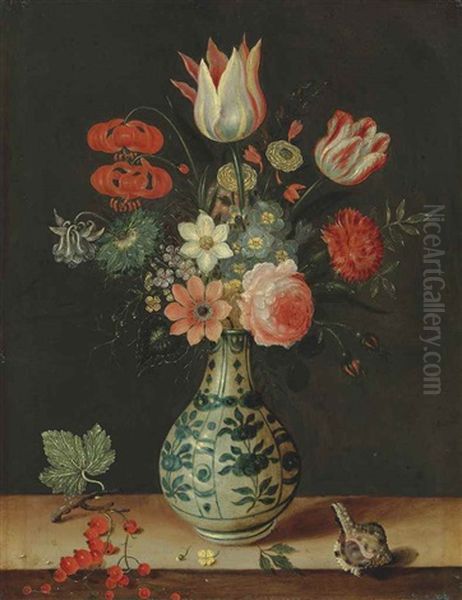

Pieter Binoit's artistic style is a compelling blend of late Mannerist tendencies and emerging Baroque sensibilities. His compositions often exhibit an "additive" quality, a characteristic sometimes associated with earlier Mannerist approaches, where objects are meticulously rendered and arranged, sometimes appearing as a collection of individual studies rather than a fully integrated, atmospheric whole. However, he combined this with a Baroque interest in rich color, dramatic lighting, and a sense of tangible presence.

A key feature of Binoit's work is his remarkable attention to detail. Each petal, leaf, insect, or piece of fruit is rendered with painstaking precision, showcasing his keen observational skills and technical mastery. Textures are vividly conveyed, from the velvety softness of a peach to the cool gleam of a glass vase or the intricate patterns on a piece of porcelain. This hyper-realism invited close scrutiny from the viewer, encouraging contemplation of the natural world's beauty and complexity.

His use of color is typically rich and vibrant. He employed a bright palette, often setting luminous flowers and fruits against darker, more subdued backgrounds, which enhanced their visual impact. This contrast, a hallmark of Baroque lighting (chiaroscuro), created a sense of depth and drama within his compositions. While not as overtly theatrical as some Italian or Flemish Baroque masters, Binoit's handling of light and shadow effectively models forms and highlights textures.

Perspective in Binoit's paintings can sometimes appear slightly elevated or unconventional, allowing for a clearer view of the objects arranged on a tabletop. This approach, common in early still life, ensures that each element is distinctly visible. His arrangements, though carefully composed, can sometimes feel dense, packed with a variety of items that demonstrate both nature's bounty and the artist's skill. For example, in his fruit pieces, baskets often overflow with an assortment of grapes, peaches, plums, and cherries, sometimes accompanied by nuts, foliage, and insects.

Key Themes and Symbolism in Binoit's Oeuvre

Like many still life paintings of the period, Binoit's works are often imbued with multiple layers of meaning, extending beyond mere representation. The objects depicted frequently carry symbolic connotations, reflecting on themes of life, death, transience, and spirituality.

Vanitas: The theme of Vanitas, reminding the viewer of the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures and the inevitability of death, is a common thread in Baroque still life. While Binoit's works may not always include overt Vanitas symbols like skulls or hourglasses, the inherent transience of his subjects – cut flowers that will wilt, ripe fruit that will decay, insects that signify corruption – subtly alludes to this concept. The beauty captured on canvas is ephemeral in reality, prompting contemplation on the passage of time and the pursuit of more lasting, spiritual values.

Celebration of Nature and Divine Creation: Conversely, Binoit's still lifes can also be seen as a celebration of God's creation. The meticulous depiction of nature's diversity and beauty – the vibrant colors of flowers, the lusciousness of fruit – reflected a contemporary appreciation for the natural world as a manifestation of divine artistry. Collecting and studying exotic plants and shells was a popular pastime, and paintings like Binoit's served as a permanent record of these wonders.

Exoticism and Wealth: The inclusion of exotic flowers, fruits, and objects like Chinese porcelain (wanli kraak porcelain was highly prized) in Binoit's paintings also spoke to the expanding global trade networks of the 17th century. These items were luxury goods, and their depiction could signify the wealth and worldliness of the patron or reflect a broader societal fascination with the exotic. A painting featuring tulips, for instance, could allude to "Tulip Mania," the speculative bubble surrounding tulip bulbs in the Netherlands, which peaked shortly after Binoit's death but was building during his active years.

Sensory Appeal: Beyond intellectual symbolism, Binoit's paintings appeal directly to the senses. The viewer can almost smell the fragrance of the flowers, taste the sweetness of the fruit, and feel the coolness of the glass. This emphasis on sensory experience is characteristic of Baroque art, which sought to engage the viewer emotionally and viscerally.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several works exemplify Pieter Binoit's skill and thematic concerns. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné is complex for artists of this period, key attributed paintings highlight his contributions.

"Flowers in a Glass Beaker" (c. 1620): This work, or similar compositions attributed to him, showcases Binoit's mastery in depicting floral arrangements. Typically, such paintings feature a variety of flowers, often including tulips, roses, irises, carnations, and columbines, artfully arranged in a transparent glass beaker or vase. The transparency of the glass allows Binoit to demonstrate his skill in rendering reflections and the refraction of light through water and glass. Insects, such as butterflies, caterpillars, or flies, are often present, adding to the naturalism and symbolic complexity (butterflies for resurrection, flies for decay or transience). The flowers themselves might carry specific meanings: roses for love or martyrdom, lilies for purity, irises for royalty or sorrow.

"Still Life with Iris" (or similar titles): Paintings focusing on specific prominent flowers like the iris demonstrate Binoit's ability to capture the unique character and delicate structure of individual blooms. The iris, with its majestic form and rich colors (often purple, blue, or white), was a popular subject. In such works, Binoit would pay close attention to the velvety texture of the petals and the subtle gradations of color. The dramatic lighting would make the flower stand out against a dark background, emphasizing its sculptural quality.

"Basket of Fruits and Vegetables": This type of composition allowed Binoit to display a cornucopia of nature's produce. A woven basket might be filled to overflowing with grapes, peaches, plums, apples, pears, and perhaps vegetables like artichokes or asparagus. The varied textures and colors of these items provided a rich visual feast. Again, insects or dewdrops might be added to enhance the illusion of reality and add symbolic layers. Such paintings celebrated earthly abundance but could also subtly hint at the cycle of growth and decay. The careful arrangement, often with items spilling out of the basket onto the table, created a sense of immediacy and informal richness.

His works often feature a characteristic dark, undefined background, which serves to push the brightly lit subjects forward, creating a strong sense of three-dimensionality. The tabletops are usually simple, wooden surfaces, ensuring that the focus remains entirely on the meticulously rendered objects.

Influences and Contemporaries: A Wider Network

Pieter Binoit did not work in isolation. He was part of a network of artists, and his style reflects both direct tutelage and broader artistic currents.

His primary influence was undoubtedly his master, Daniel Soreau. The Soreau workshop in Hanau was a crucible for still-life painting, and Binoit inherited its emphasis on detailed realism and often dense compositions. Daniel Soreau's own works, though fewer survive, show a similar interest in varied textures and the arrangement of diverse objects.

Georg Flegel in Frankfurt was a crucial contemporary. Flegel's intimate and highly detailed still lifes, often featuring meals, fruit, and flowers, set a high standard for the genre in Germany. There are stylistic affinities between Flegel and Binoit, particularly in their meticulous rendering and appreciation for the humble beauty of everyday objects.

The influence of Netherlandish still life painting is undeniable. Artists from the Low Countries were pioneers in this genre.

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder and his circle, including Balthasar van der Ast, were renowned for their symmetrical and brilliantly colored flower pieces, often featuring rare and exotic blooms. Their precision and encyclopedic approach to botany would have resonated with Binoit.

Osias Beert the Elder, working in Antwerp, was known for his "breakfast pieces" (ontbijtjes) and fruit still lifes on pewter or ceramic dishes, characterized by a high viewpoint and a careful, almost jewel-like rendering of objects.

Clara Peeters, another Antwerp artist, excelled in detailed still lifes featuring food, drink, and expensive tableware, often with remarkable reflective surfaces.

Jacob van Hulsdonck (1582–1647), also active in Antwerp and later Amsterdam, specialized in fruit still lifes, often in baskets or on porcelain dishes, with a clarity and precision that Binoit would have appreciated.

Floris van Schooten (c. 1585/90–1656), active in Haarlem, painted kitchen and market scenes, as well as fruit and breakfast still lifes. His compositions, sometimes simpler and more rustic, show another facet of the genre's development in the Netherlands.

Later, but emerging from similar traditions, artists like Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–1680) and Pieter Claesz (1597/98–1660) in Haarlem would develop the "monochrome banketje," a more subdued and tonally unified style of still life, but the earlier, more colorful tradition was prevalent during Binoit's formative years.

Within Germany, other artists were also contributing to the still life tradition. Sebastian Stoskopff (1597–1657), though slightly younger and active primarily in Strasbourg, developed a highly illusionistic style, often with Vanitas themes, and shared an interest in meticulous detail. The Soreau brothers, Isaak Soreau and Peter Soreau, Binoit's fellow pupils or workshop colleagues, continued to produce still lifes in a similar vein in Hanau. Further north, artists like Georg Hinz (c. 1630-1688) would later carry on the German still life tradition, though he belongs to a slightly later generation.

Binoit's work, therefore, can be seen as a German interpretation of a broader Northern European phenomenon, inflected by local traditions and the specific artistic environment of the Rhine-Main region.

Legacy and Significance

Pieter Binoit's career, though relatively short (he died in his early forties), made a notable contribution to the establishment and development of still life painting in Germany. He was among the first generation of German artists to specialize in this genre, helping to popularize it among patrons in Frankfurt, Hanau, and Cologne.

His paintings are prized for their technical skill, their vibrant beauty, and their rich symbolic content. They reflect the period's fascination with the natural world, the impact of global trade, and the complex interplay of worldly pleasure and spiritual contemplation that characterized Baroque culture. Binoit successfully bridged the meticulous detail inherited from late Renaissance and Mannerist traditions with the burgeoning dynamism and sensory richness of the Baroque.

While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his Dutch or Flemish contemporaries like Jan Brueghel the Elder or Ambrosius Bosschaert, Binoit holds an important place in the history of German art. His works are found in significant museum collections and are valued by connoisseurs of early still life painting. He represents a key moment when German artists, despite the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War, were actively participating in and shaping major European artistic trends.

His legacy also lies in his role within the Hanau school, contributing to a local tradition of still-life painting that persisted through the Soreau family and other artists. He demonstrated that German painters could achieve a level of refinement and expressive power in still life comparable to their Netherlandish counterparts.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Pieter Binoit was a dedicated and highly skilled practitioner of still life painting in early 17th-century Germany. His works, whether depicting opulent floral arrangements, bountiful fruit baskets, or carefully laid out banquet items, are characterized by their meticulous execution, vibrant colors, and thoughtful, often symbolic, compositions. Born into a world of religious and political upheaval, he created images of beauty, abundance, and quiet contemplation that offered an alternative vision to the turmoil of his times.

His art provides a valuable insight into the cultural preoccupations of the early Baroque period: the burgeoning interest in scientific observation, the allure of exotic goods from distant lands, and the enduring human reflection on the nature of existence and the transience of earthly delights. As an artist who skillfully navigated the transition from Mannerism to Baroque, and who helped to establish still life as a significant genre in Germany, Pieter Binoit deserves recognition as a master whose detailed and luminous visions continue to captivate viewers centuries later. His paintings are a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the beauty of the world and to provoke thought and wonder.