Evaristo Baschenis stands as a singular figure in the rich panorama of 17th-century Italian Baroque art. An artist of profound sensitivity and technical brilliance, he carved a unique niche for himself, becoming the foremost painter of musical still lifes, a genre he virtually pioneered and brought to an unprecedented level of poetic and visual sophistication. His canvases, often hushed and imbued with a melancholic beauty, invite contemplation on the nature of art, music, time, and the ephemeral allure of worldly possessions. Operating primarily from his native Bergamo in Lombardy, Baschenis developed a distinctive style that, while rooted in Lombard naturalism and influenced by broader European trends, remained intensely personal and instantly recognizable.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Bergamo

Born in Bergamo in 1617 into a family with a long-standing artistic lineage, Evaristo Baschenis was immersed in a creative environment from his earliest years. The Baschenis family had been active as painters, often engaged in decorating local churches and chapels in the valleys around Bergamo, for generations. This familial heritage undoubtedly provided young Evaristo with his initial artistic training and an appreciation for the craft of painting. While specific details of his apprenticeship are scarce, it is clear that he absorbed the prevailing Lombard artistic traditions, characterized by a strong commitment to realism and a keen observation of the natural world, a legacy tracing back to earlier Lombard masters like Vincenzo Foppa and later refined by figures such as Moretto da Brescia and Giovanni Battista Moroni.

Bergamo, though not a primary artistic center on the scale of Rome, Venice, or Florence, possessed a vibrant cultural life. It was a city that valued music, and this local appreciation would become central to Baschenis's artistic identity. Furthermore, his decision to enter the priesthood, becoming Don Evaristo Baschenis, added another dimension to his persona. This dual role as artist and cleric is not uncommon in art history, with figures like Fra Angelico or Lorenzo Monaco preceding him, but for Baschenis, it perhaps deepened his contemplative approach to his subjects. His life seems to have been largely centered in Bergamo, where he established his workshop and cultivated a circle of patrons and admirers.

The Emergence of a Unique Vision: Musical Instruments as Protagonists

The still life genre, or natura morta as it came to be known in Italy, was gaining traction across Europe in the 17th century. Dutch and Flemish painters like Pieter Claesz, Willem Kalf, and Jan Davidsz. de Heem were producing astonishingly detailed and often symbolically rich depictions of banquet tables, floral arrangements, and collections of precious objects. While Italy had its own tradition of still life, often emerging from studies of fruit and flowers, Baschenis took a remarkably innovative path. He chose to elevate musical instruments to the primary subject of his paintings, a focus that was virtually unprecedented in its sustained dedication.

Before Baschenis, musical instruments often appeared in allegorical paintings, portraits of musicians, or as subsidiary elements in larger compositions. Artists like Titian or Caravaggio might include a lute or a violin to denote a sitter's refinement or to contribute to a scene's narrative. However, Baschenis was arguably the first to consistently make these instruments the silent protagonists of his canvases. He treated them not merely as objects but as entities possessing their own character, history, and evocative power. This specialization allowed him to explore the formal qualities of these instruments—their elegant curves, polished surfaces, and intricate details—with an almost devotional intensity.

His decision to focus on musical instruments was likely multifaceted. His own documented skills as a musician would have given him an intimate understanding and appreciation of their form and function. Furthermore, Bergamo and nearby Cremona were at the heart of a flourishing tradition of stringed instrument making. The workshops of the Amati family, and later those of Stradivari and Guarneri in Cremona, were producing some ofthe finest violins, cellos, and lutes the world had ever seen. Baschenis was a contemporary of the great luthier Nicolò Amati, and his paintings often feature instruments rendered with such precision that they serve as valuable historical documents for musicologists and instrument makers.

Artistic Style: Realism, Chiaroscuro, and Compositional Harmony

Evaristo Baschenis’s style is characterized by a meticulous realism, a sophisticated use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and a masterful sense of composition. His paintings are typically set against dark, undefined backgrounds, a technique reminiscent of Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti, such as Artemisia Gentileschi or Jusepe de Ribera). This dramatic lighting serves to highlight the instruments, making them emerge from the gloom with a palpable presence. The play of light across the varnished wood of a lute, the sheen of a violin’s belly, or the intricate inlay of a guitar is rendered with extraordinary skill.

Baschenis paid scrupulous attention to the textures of his subjects: the smooth, polished wood, the tautness of strings, the softness of velvet drapes or patterned carpets often used as a base for his arrangements, and even the accumulated dust on neglected instruments. This tactile quality invites the viewer to imagine reaching out and touching these objects. His depiction of dust, in particular, became a hallmark, subtly suggesting the passage of time and the silence that has fallen over these once-vibrant sources of music.

Compositionally, Baschenis arranged his instruments with a keen eye for balance and geometric harmony. Lutes, violins, cellos, mandolins, guitars, and occasionally wind instruments or keyboard instruments like spinets, are often artfully strewn across a table, sometimes covered with an oriental rug or a rich brocade. He employed strong diagonals and complex foreshortening to create a sense of depth and dynamism, drawing the viewer's eye into the pictorial space. Despite the apparent casualness of some arrangements, there is an underlying order and a carefully considered interplay of forms, lines, and volumes. This geometric underpinning lends his compositions a sense of stability and intellectual rigor, even amidst the apparent disorder of a musician's studio.

Key Themes and Symbolism in Baschenis's Oeuvre

While Baschenis’s paintings are, on the surface, exquisite depictions of musical instruments, they resonate with deeper thematic concerns common in Baroque art, particularly the concept of Vanitas. The instruments themselves, capable of producing beautiful but transient music, can be seen as symbols of the fleeting nature of worldly pleasures and human endeavors. The frequent inclusion of dust further emphasizes this sense of transience and the inevitable decay that awaits all earthly things.

In some works, more explicit Vanitas symbols appear, such as an hourglass, a snuffed-out candle, or decaying fruit, reinforcing the message of memento mori (remember you must die). However, even without these overt symbols, the silent, often abandoned-looking instruments evoke a sense of melancholy and the passage of time. They seem to wait for a musician's touch to bring them back to life, their silence a poignant reminder of music's ephemeral nature.

Beyond Vanitas, Baschenis’s works also celebrate the beauty and craftsmanship of the instruments themselves and, by extension, the art of music. In an era when music was an integral part of social and cultural life, these paintings would have appealed to a sophisticated clientele that appreciated both the visual arts and music. The instruments can also be interpreted as symbols of harmony, order, and intellectual pursuit, reflecting Neo-Platonic ideas about the mathematical basis of beauty and the "music of the spheres."

The presence of sheet music, often legible, in some paintings adds another layer of meaning, directly referencing specific compositions or the act of musical creation. Occasionally, books or globes appear, linking music to broader intellectual and worldly knowledge, as seen in his Still Life with Musical Instruments and a Globe.

Representative Masterpieces

Evaristo Baschenis produced a significant body of work, much of which is now housed in prestigious museums and private collections. Several paintings stand out as quintessential examples of his artistry.

_Still Life with Musical Instruments_ (Accademia Carrara, Bergamo): This is perhaps one ofhis most iconic works. A collection of lutes, a violin, a cello, and a guitar are artfully arranged on a table covered with a rich, patterned carpet. The instruments are rendered with breathtaking precision, their polished surfaces gleaming in the focused light. A subtle layer of dust coats some of the instruments, lending a poignant air of neglect and the passage of time. The complex interplay of curves and angles, combined with the deep shadows, creates a composition that is both dynamic and harmonious.

_The Agliardi Triptych_ (Private Collection): A more unusual work for Baschenis, this triptych features portraits of members of the Agliardi family, prominent Bergamasque nobles, depicted with musical instruments. While incorporating portraiture, the instruments remain central, rendered with Baschenis's characteristic care. This work highlights his connection to local patrons and the importance of music in aristocratic circles. It also shows his versatility in combining his still life expertise with figural representation, a skill perhaps honed by his friend, the Bergamasque portrait painter Carlo Ceresa.

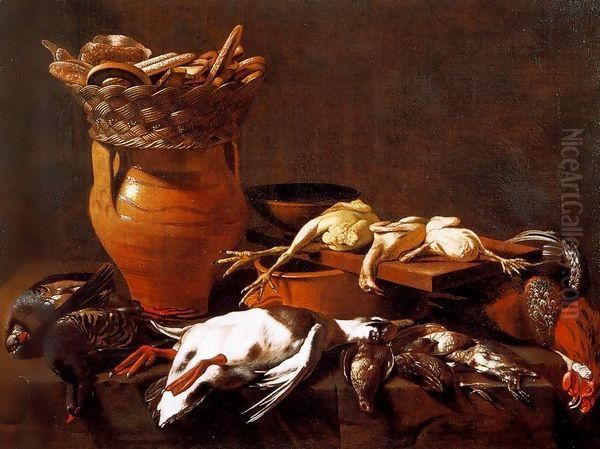

_Kitchen Still Life_ (Accademia Carrara, Bergamo): While best known for musical instruments, Baschenis also painted kitchen still lifes, though less frequently. These works, often featuring copper pots, game, and vegetables, demonstrate his broader capabilities within the natura morta genre and his connection to a Lombard tradition that included artists like Vincenzo Campi. However, even in these, his meticulous attention to texture and light is evident.

_Still Life of Musical Instruments on a Table Draped With a Carpet_ (Private Collection): Another exemplary piece, this painting (measuring approximately 61.5cm x 81cm) showcases his ability to create a sense of opulent disarray. The rich carpet provides a luxurious ground for the carefully placed lutes and violins, their forms catching the light in a manner that emphasizes their three-dimensionality and the quality of their craftsmanship.

_Lute Player and Hourglass_: This title, or variations of it, refers to compositions where the human element is more directly implied or even subtly present, and the inclusion of an hourglass directly points to the Vanitas theme, linking the transience of music with the inexorable passage of time.

_Nature morte au globe terrestre_ (Still Life with Terrestrial Globe): This work, likely similar to or the same as Still Life with Musical Instruments and a Globe, broadens the symbolic scope, connecting the harmony of music with the order of the cosmos and the pursuit of knowledge, a common theme in Renaissance and Baroque intellectual thought.

Influences, Contemporaries, and the Lombard Context

Baschenis’s art did not develop in a vacuum. He was undoubtedly aware of the broader currents in European still life painting. The meticulous realism of Dutch and Flemish artists, as mentioned, provided a general backdrop. The dramatic chiaroscuro popularized by Caravaggio and his followers, such as Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia, as well as Spanish masters like Francisco de Zurbarán who also excelled in still life, clearly informed Baschenis's use of light.

Within Italy, the Lombard tradition of naturalism was a foundational influence. Artists from this region had long shown a preference for direct observation and unidealized representation. Baschenis can be seen as a late exponent of this tradition, applying its principles to the specialized field of still life. He was also a contemporary of other Italian still life painters, though his focus on musical instruments set him apart. For instance, the Neapolitan school, with artists like Paolo Porpora and Giovan Battista Ruoppolo, excelled in lush depictions of flowers, fruit, and fish, often with a more exuberant and less contemplative mood than Baschenis's work. In Rome, artists like Michelangelo Pace (known as "Michelangelo da Campidoglio") were known for their fruit and flower pieces.

In Bergamo itself, Baschenis was a leading figure. He was friends with Carlo Ceresa (1609-1679), a notable portrait painter whose sober realism shares some affinities with Baschenis's approach to objects. Baschenis also had pupils and followers who continued his specialty. The most significant of these was Bartolomeo Bettera (c. 1639 – c. 1699), also from Bergamo, whose works are often very close in style and subject matter to his master's, sometimes leading to attribution difficulties. Bettera, in turn, likely influenced his own son, Bonaventura Bettera.

Baschenis's connection with the instrument-making workshops of Cremona, including figures like Nicolò Amati, was crucial. His paintings are not just artistic creations but also valuable documents of the luthier's art of the period. He may have visited Venice, a major musical and artistic hub, where he could have encountered the works of Venetian painters and further absorbed the rich musical culture of the Serenissima. Artists like Bernardo Strozzi, active in Venice, sometimes incorporated strong still life elements into their genre scenes. The Jesuit painter Jacques Courtois (Giacomo Cortese, known as il Borgognone), though primarily a battle painter, was also active in Italy during Baschenis's lifetime and represents the international artistic exchange of the period.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Despite his unique achievements, Evaristo Baschenis, like many specialized still life painters of his era, fell into relative obscurity after his death in 1677. The grand narratives of history painting and religious epics, championed by artists like Guido Reni or Pietro da Cortona, often overshadowed the more intimate genre of still life in subsequent art historical accounts. It was not until the late 19th and, more significantly, the 20th century that art historians began to re-evaluate the contributions of still life painters.

Scholarly research and a renewed appreciation for Baroque art led to the rediscovery of Baschenis. His technical mastery, the poetic intensity of his vision, and his unique specialization earned him a prominent place in the history of Italian art. He is now recognized as the preeminent master of the musical still life and one of Italy's most original still life painters. Modern art historians have lauded him, with some referring to him as the "mute singer of Italian still life," a testament to the silent eloquence of his canvases.

His works have been featured in major exhibitions, including those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at La Scala Theatre Museum in Milan, bringing his art to a wider international audience. These exhibitions have not only highlighted his artistic merit but also his importance for music history, as his paintings offer invaluable insights into the musical instruments of the Baroque period. Collectors and museums actively seek his works, and his paintings in the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo remain a proud testament to his local origins and international stature.

Conclusion: The Enduring Resonance of Baschenis

Evaristo Baschenis was more than just a painter of objects; he was a poet of silence, a chronicler of musical craftsmanship, and a subtle philosopher of time and transience. His decision to focus on musical instruments allowed him to create a body of work that is both visually stunning and intellectually engaging. Through his meticulous realism, his dramatic use of light, and his harmonious compositions, he transformed inanimate objects into resonant symbols.

His paintings capture the soul of music even in its absence, the polished wood and taut strings of his lutes and violins seeming to hold the memory of melodies played and the anticipation of future harmonies. In a world saturated with noise and fleeting images, Baschenis’s quiet, contemplative canvases offer a space for reflection, inviting us to appreciate the beauty of craftsmanship, the poignancy of time's passage, and the enduring power of art to speak across centuries. His legacy is that of an artist who, by narrowing his focus, achieved a universal and timeless appeal, securing his position as a true maestro of the Baroque still life.