Pietro Paolini, a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque art, stands as a testament to the enduring power of Caravaggio's revolution and the rich artistic traditions of regional Italian schools. Born in Lucca in 1603 and dying there in 1681, Paolini's life and career bridged a dynamic period of artistic innovation and consolidation. His work is characterized by a compelling synthesis of dramatic tenebrism, a keen observational naturalism, and a sophisticated understanding of narrative composition, often infused with a unique theatrical sensibility. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic development, key works, and lasting legacy of this intriguing painter from Tuscany.

Early Life and Formative Years in Lucca and Rome

Pietro Paolini was born on June 3, 1603, in Lucca, a historically independent city-state in Tuscany with its own distinct cultural and artistic heritage. He hailed from a respectable family; his father was Tommaso Paolini and his mother, Ginevra di Raffaello Raffaelli. Lucca, while not as dominant an artistic center as Florence, Rome, or Venice, possessed a vibrant local school and a history of artistic patronage that provided a foundational environment for a budding artist. Recognizing his son's talent and inclination towards the arts, Tommaso Paolini made the pivotal decision to send the young Pietro, at the age of sixteen in 1619, to Rome to further his artistic education.

Rome in the early 17th century was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, still reverberating with the seismic impact of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, who had died in 1610. Caravaggio's revolutionary approach—his dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark), his unidealized, naturalistic depiction of figures often drawn from everyday life, and the raw emotional power of his religious scenes—had captivated and challenged a generation of artists. It was into this charged atmosphere that Paolini arrived.

In Rome, Paolini entered the workshop of Angelo Caroselli (1585–1652). Caroselli was an eclectic and somewhat enigmatic figure, known for his skill as a copyist, his pastiches of earlier masters, and his own original works that often featured genre scenes, allegories, and subjects with a slightly macabre or sensual undertone. Caroselli's studio would have exposed Paolini to a wide range of stylistic influences and technical approaches. More importantly, Caroselli himself was an admirer of Caravaggio and his followers, the so-called Caravaggisti. This apprenticeship provided Paolini with direct access to the Caravaggesque idiom, which would become a defining characteristic of his art.

The Caravaggesque Milieu and Early Influences

During his extended stay in Rome, which lasted until around 1628 or 1629, Paolini immersed himself in the artistic currents of the city. The influence of Caravaggio was paramount. Paolini would have studied Caravaggio's masterpieces in Roman churches and collections, absorbing the master's dramatic lighting, his focus on human emotion, and his ability to make sacred stories intensely present and relatable.

Beyond Caravaggio himself, Paolini was significantly influenced by the first generation of Caravaggisti. Bartolomeo Manfredi (c. 1582–1622) was particularly important. Manfredi had popularized certain Caravaggesque themes, such as concert scenes, fortune tellers, and cardsharps, creating what became known as the "Manfrediana Methodus." Paolini's own later depictions of musicians and genre scenes owe a debt to Manfredi's interpretations. Other prominent Caravaggisti active or whose works were visible in Rome included Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi, both of whom tempered Caravaggio's raw naturalism with a greater elegance and refinement. French artists like Valentin de Boulogne (whom some sources suggest Paolini knew, possibly the "Valentino de Buren" or "Valentino Bonguelli" mentioned in some accounts, though de Boulogne is the most prominent Caravaggist "Valentin" of the era) and Simon Vouet (in his early Caravaggesque phase) also contributed to the vibrant artistic dialogue. The Dutch "Utrecht Caravaggisti" such as Gerrit van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen, who brought their own Northern European sensibility to the style, were also part of this Roman melting pot.

Paolini's Roman period was crucial for developing his technical skills and artistic vision. He learned to master the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, to model figures with a strong sense of volume, and to compose scenes with a focus on psychological interaction. His early works from this period, while not always securely dated or attributed, begin to show his assimilation of these Caravaggesque principles.

The Venetian Interlude: Broadening Horizons

Around 1628, before returning definitively to Lucca, Paolini spent approximately two years in Venice. This sojourn, though relatively brief, was significant for broadening his artistic palette. Venice, with its distinct artistic tradition, offered a different set of influences. The Venetian school, dominated by titans like Titian, Tintoretto, and Paolo Veronese, was renowned for its rich colorism, its dynamic compositions, and its atmospheric effects. While Caravaggism emphasized stark contrasts and sculptural form, Venetian painting often prioritized painterly texture, nuanced light, and the expressive power of color.

In Venice, Paolini would have encountered the legacy of these High Renaissance masters and the work of contemporary Venetian painters. This exposure likely encouraged him to explore a richer chromatic range and perhaps a more fluid brushwork than was typical of the more austere Roman Caravaggisti. The Venetian emphasis on grand narrative compositions and the depiction of opulent textures may also have left an impression. This experience allowed Paolini to temper the sometimes harsh drama of Caravaggism with a Venetian sensitivity to color and atmosphere, resulting in a more nuanced and personal style. Artists like Palma Giovane, who carried the Venetian tradition into the 17th century, would have been active, and the works of earlier masters like Jacopo Bassano, with his rustic genre scenes and dramatic nocturnal effects, might also have resonated with Paolini.

Return to Lucca: Maturity and the Accademia del Naturale

By 1631, Pietro Paolini was back in his native Lucca, where he would remain for the rest of his life, becoming the leading painter of his generation in the city. He brought with him the sophisticated artistic language he had forged in Rome and Venice. In Lucca, he married Maria Angela Giannini and established a successful workshop.

A significant development in Paolini's Lucchese period was the founding of the "Accademia del Naturale" (Academy of the Natural) around 1639 or shortly thereafter. This academy, which he established at his own expense, was dedicated to promoting drawing from life and the study of nature, principles central to Caravaggio's revolution and a reaction against the lingering artificialities of Mannerism. The academy aimed to foster a new aesthetic sensibility in Lucca, grounded in direct observation. It attracted a number of pupils who would go on to become notable artists in their own right, including his two sons, Francesco and Giovanni Andrea Paolini, as well as Girolamo Scaglia, Antonio Franchi (sometimes referred to as Antonio Franchini), Simone del Tintore, and Pietro Ricchi (il Lucchese), though Ricchi also had extensive experience elsewhere. Through his teaching, Paolini played a crucial role in shaping the artistic landscape of Lucca in the mid-17th century.

His own work during this mature period demonstrates a full command of his powers. He produced a range of paintings, including large-scale altarpieces for local churches, private devotional works, allegorical subjects, mythological scenes, and striking genre paintings, particularly his renowned concert scenes.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Pietro Paolini's oeuvre is diverse, but certain themes and stylistic characteristics recur, showcasing his artistic preoccupations and strengths.

Religious Paintings:

Paolini executed numerous religious commissions, often marked by their dramatic intensity and emotional depth.

The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew (examples exist, one notable version for the Oratory of SS. Crocifisso de’ Bianchi in Lucca, now in Villa Guinigi): This subject, popular in the Baroque era, allowed Paolini to explore themes of faith, suffering, and divine revelation through dynamic composition and expressive figures, often employing strong chiaroscuro to heighten the drama.

The Virgin and Saints or The Great Picture in the Library of S. Frediano (Basilica di San Frediano, Lucca): Large altarpieces like these demonstrated his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and to convey a sense of solemn grandeur appropriate for their ecclesiastical settings. His depiction of saints often carries a profound human quality, avoiding idealized perfection in favor of relatable piety.

Isaac and Esau (Denver Art Museum): This Old Testament scene showcases his narrative skill, capturing the tension and deception of the moment with psychological acuity. The interplay of gestures and expressions is carefully orchestrated.

Allegorical and Mythological Works:

Paolini had a penchant for allegorical subjects, which allowed him to explore complex ideas through symbolic imagery.

The Allegory of the Five Senses (versions exist, e.g., Walters Art Museum, Baltimore): This was a popular theme in Baroque art. Paolini’s interpretations typically feature figures representing Sight, Hearing, Smell, Taste, and Touch, often engaged in activities that evoke each sense. These works are notable for their rich detail, the still-life elements incorporated, and the often enigmatic or contemplative mood.

Ages of Man or The Ages of Life (series): These allegorical series, sometimes painted on furniture, depicted the different stages of human existence, often with a moralizing undertone. They reflect the Baroque fascination with transience, mortality, and the human condition.

Allegories of the Arts and Sciences (e.g., Music, Astronomy, Geometry, Philosophy): Similar to the Ages of Man, these works personified intellectual and artistic pursuits, often set within richly detailed interiors.

Genre Scenes and Concerts:

Perhaps Paolini's most distinctive and celebrated works are his genre scenes, particularly those depicting musicians.

The Concert (versions exist, e.g., Louvre, Paris; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles): These paintings capture groups of musicians, often in contemporary dress, engrossed in their performance. Paolini excels in rendering the varied textures of fabrics and instruments, the expressive faces of the figures, and the intimate, convivial atmosphere. These works recall Manfredi's concert scenes but possess Paolini's unique blend of realism and quiet theatricality. The figures are often half-length, brought close to the picture plane, engaging the viewer directly.

Card Players or Drinkers: Following the Caravaggesque tradition, Paolini also painted scenes of everyday life, sometimes with a hint of roguishness or social commentary, though generally with less overt drama than Caravaggio's own depictions of such subjects.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Pietro Paolini's style is a sophisticated amalgamation of his diverse influences, resulting in a distinctive artistic voice.

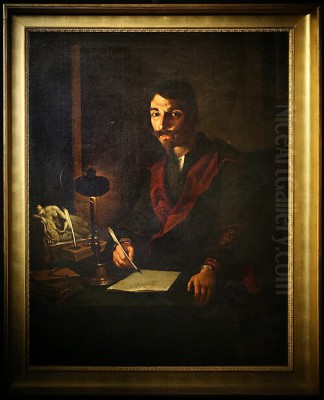

Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism: The most evident legacy of Caravaggio in Paolini's work is his masterful use of chiaroscuro. He employed strong contrasts of light and shadow to model figures, create a sense of three-dimensionality, and heighten the dramatic impact of his scenes. While not always as starkly tenebrist as Caravaggio, his lighting is consistently purposeful, directing the viewer's eye and imbuing his compositions with a palpable atmosphere.

Naturalism and Realism: Paolini adhered to the Caravaggesque principle of depicting figures with a high degree of naturalism. His saints, mythological figures, and everyday people are rendered with a sense of physical presence and individual character. He paid close attention to anatomical accuracy, the texture of skin, and the fall of drapery, avoiding excessive idealization. This realism lends an immediacy and believability to his narratives.

Color Palette: While rooted in the often somber tones of Caravaggism, Paolini's palette could also be quite rich, likely a result of his Venetian experience. He was capable of employing vibrant reds, deep blues, and warm earth tones, often juxtaposed effectively to create visual interest and emotional resonance. His handling of color contributes to the overall harmony and sometimes the opulence of his compositions.

Composition: Paolini's compositions are generally well-balanced and thoughtfully constructed. He often favored half-length figures in his genre and allegorical works, bringing the action close to the viewer and fostering a sense of intimacy. In his larger religious works, he managed complex multi-figure arrangements with clarity and narrative coherence. There is often a sense of arrested movement or a pregnant pause in his scenes, a theatrical quality that invites contemplation.

Psychological Insight: A notable feature of Paolini's art is his ability to convey the psychological states of his figures. Through subtle gestures, facial expressions, and the interplay of gazes, he endows his characters with an inner life, making their joys, sorrows, and contemplations tangible to the viewer. This is particularly evident in his concert scenes, where the shared experience of music creates a bond between the figures.

Theatricality: Many of Paolini's works possess a distinct, if understated, theatricality. His figures often seem like actors on a dimly lit stage, their poses and expressions carefully chosen for narrative effect. This quality may reflect the general Baroque interest in drama and spectacle, as well as Paolini's own artistic temperament. It is a controlled theatricality, however, more focused on internal emotion than on overt melodrama.

Influence and Legacy

Pietro Paolini was the preeminent painter in Lucca for much of the 17th century. Through his own prolific output and his activities at the Accademia del Naturale, he exerted a significant influence on the local art scene. He trained a new generation of Lucchese painters, instilling in them the principles of naturalism and solid draftsmanship. His students, such as Girolamo Scaglia and Antonio Franchi, carried forward aspects of his style.

While his fame did not reach the international heights of some of his Roman or Venetian contemporaries like Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona, or later Luca Giordano, Paolini's work was esteemed by connoisseurs and patrons. His paintings were acquired by collectors both within Italy and beyond. In the broader context of Italian Baroque art, Paolini is recognized as a distinctive interpreter of the Caravaggesque tradition, one who successfully melded its dramatic realism with a personal sensibility that incorporated elements of Venetian colorism and a refined, almost classical sense of order.

His genre scenes, particularly the concert paintings, are considered among the finest examples of this type produced in Italy during the period. They stand alongside similar works by artists like Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia Gentileschi, and the aforementioned Manfredi and Valentin de Boulogne, contributing to a rich vein of Baroque painting that focused on the depiction of everyday life and leisure.

Some art historians have noted a certain unevenness in his output, which is not uncommon for prolific artists with active workshops. However, his best works demonstrate a high level of technical skill, artistic intelligence, and emotional depth. His religious paintings, while sometimes criticized by later commentators for a perceived excess of drama (a common critique leveled at Baroque art in general), were effective in their devotional purpose and often display a profound empathy for their subjects. His depictions of female figures, in particular, have been praised for their sensitivity and strength.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of a Lucchese Master

Pietro Paolini died in Lucca on April 12, 1681, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant artistic legacy in his native city. He navigated the complex artistic currents of his time with skill and individuality, forging a style that was both indebted to the great innovators like Caravaggio and uniquely his own. His commitment to naturalism, his mastery of light and shadow, his nuanced psychological portrayals, and the quiet theatricality of his compositions continue to engage and impress viewers today.

As a key figure in the Lucchese school and an important representative of the Caravaggesque movement outside of its primary centers, Pietro Paolini holds a secure place in the history of Italian Baroque art. His paintings, whether depicting the solemnity of a martyrdom, the intellectual pursuit of an allegory, or the shared joy of a musical performance, reveal an artist deeply attuned to the human condition, capable of rendering its complexities with both technical brilliance and profound empathy. His work serves as a vital reminder of the richness and diversity of artistic expression that flourished across the Italian peninsula during one of its most dynamic artistic periods, and the enduring impact of artists who, like Paolini, dedicated their lives to the pursuit of visual truth and beauty. His art continues to be studied and appreciated, ensuring that this "Cavaliere del Pennello" (Knight of the Brush), as he was sometimes known, remains a compelling voice from Italy's golden age of painting.