Adam de Coster (c. 1586–1643) stands as a fascinating, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in the rich tapestry of Flemish Baroque art. Hailing from Mechelen, he carved a unique niche for himself, earning the evocative Latin moniker "Pictor Noctium" – the Painter of the Night. This title aptly describes his masterful specialization in nocturnal scenes, particularly those illuminated by the warm, dramatic glow of a single candle. His work, deeply imbued with the spirit of Caravaggism, resonates with a profound understanding of light and shadow, capturing intimate moments with a quiet intensity that continues to captivate audiences centuries later.

Though details of his personal life remain scarce, his artistic journey and impact are discernible through his surviving works and contemporary records. De Coster's legacy is one of atmospheric depth, psychological nuance, and a distinctive approach to the tenebrist style that swept across Europe in the early 17th century.

Early Life and Antwerp Beginnings

Born in Mechelen around 1586, Adam de Coster's early artistic training is not definitively documented. However, by approximately 1607, he was established enough to be registered as a master in the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp. This city, a vibrant artistic hub, was then dominated by the towering figure of Peter Paul Rubens, yet it also provided fertile ground for artists pursuing different stylistic paths. De Coster would spend the majority of his productive career in Antwerp, developing his signature style amidst a dynamic community of painters.

Antwerp's artistic environment was cosmopolitan, with influences flowing in from Italy and other parts of Europe. The Guild of Saint Luke was a crucial institution, regulating the art trade and fostering a sense of community among artists. De Coster's acceptance into the guild signifies his recognized skill and professional standing at a relatively young age. It was within this context that he began to explore the dramatic possibilities of artificial light, a theme that would come to define his oeuvre.

The Caravaggesque Wave and Italian Echoes

The most significant artistic influence on Adam de Coster was undoubtedly Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610). Caravaggio's revolutionary use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and dark – and his unidealized, naturalistic depiction of figures sent shockwaves through the European art world. Artists flocked to Rome to study his work, and his style was disseminated by both Italian followers like Bartolomeo Manfredi and Orazio Gentileschi, and by Northern artists who absorbed his lessons.

While direct proof of De Coster's own journey to Italy is not absolute, strong stylistic evidence and circumstantial details suggest he likely spent time there, particularly in Rome and possibly Venice, during the 1620s or 1630s. His profound understanding of tenebrism, the use of deep shadows to model figures and create dramatic focus, aligns closely with the practices of Caravaggio and his followers. The so-called "Utrecht Caravaggisti," such as Gerrit van Honthorst, Hendrick ter Brugghen, and Dirck van Baburen, had already returned from Italy by the 1620s, popularizing candlelit scenes in the Netherlands. De Coster became a leading Flemish exponent of this trend.

Unlike some Caravaggisti who emphasized raw, often violent, drama, De Coster's application of tenebrism often veers towards a more subdued, contemplative mood. His figures, bathed in the soft radiance of a hidden or partially visible candle, emerge from inky blackness, their features and gestures highlighted with a subtle, yet compelling, realism.

Pictor Noctium: The Signature Style

De Coster's renown as the "Pictor Noctium" was well-earned. He demonstrated an exceptional ability to manipulate light not just for dramatic effect, but also to create specific atmospheres and psychological states. His canvases are typically characterized by a limited palette, dominated by warm earth tones, reds, and deep browns, which are set against profound darkness. The single light source, usually a candle, becomes a focal point, its flame often shielded or just out of view, allowing for a diffused, gentle illumination that sculpts forms and creates a sense of intimacy.

His subjects often involve small groups of figures engaged in quiet activities: singers, musicians, gamblers, or individuals in moments of contemplation. These genre scenes allowed him to explore the nuances of human expression and interaction under the intimate conditions of candlelight. The light picks out a cheekbone, the curve of a hand, the texture of fabric, drawing the viewer into the hushed, concentrated world of the painting. This focus on interiority and subtle emotion distinguishes his work from the more overt theatricality of some of his contemporaries.

Key Masterpieces and Thematic Concerns

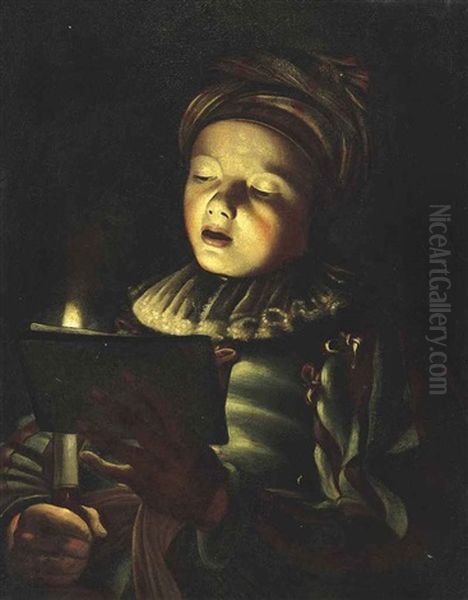

Several works exemplify Adam de Coster's distinctive style and thematic preoccupations. Among his most celebrated is Man Singing by Candlelight (circa 1625-1635). This painting, existing in several versions and copies, showcases a figure, often a young man, engrossed in song, his face illuminated by the warm glow of a candle. The intense concentration on the singer's face, the play of light on his features, and the surrounding darkness create a powerful sense of immediacy and personal experience.

Another significant work is Two Sculptors at Night in Rome (also known as Two Men with Sculptures by Candlelight, c. 1620-1625). This piece not only highlights his mastery of candlelight but also possibly alludes to his time in Italy, depicting artists or connoisseurs examining classical sculptures. The scene is imbued with a sense of scholarly pursuit and artistic appreciation, the flickering light adding a layer of mystery and reverence to the ancient artworks.

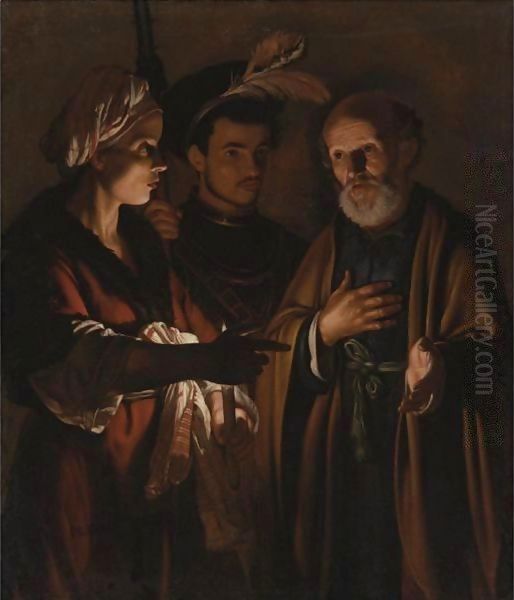

The Denial of Saint Peter is a theme De Coster tackled, a subject perfectly suited to his tenebrist approach. The dramatic biblical narrative, often set at night and involving intense emotional conflict, allowed him to explore heightened psychological states through the stark contrast of light and shadow. The accusing figures, the distraught Peter, and the symbolic brazier or candle create a compelling visual and emotional drama.

His painting The Tric-Trac Players (or Backgammon Players) captures a moment of leisure and quiet tension. The figures are gathered around a game board, their faces lit by a central candle, highlighting their expressions of concentration, anticipation, or perhaps cunning. Such genre scenes were popular, and De Coster infused them with his characteristic atmospheric depth.

A work that garnered significant attention in recent years is A Young Woman Holding a Distaff before a Lit Candle. This painting achieved a remarkable auction price of .8 million (not million as sometimes misreported, though still a very strong price for the artist) in 2023, underscoring the renewed appreciation for his skill. The painting depicts a young woman, her face softly illuminated, engaged in the domestic task of spinning. The quiet dignity and the gentle play of light are hallmarks of De Coster's intimate style.

Other works attributed to him, such as The Concert Party and various depictions of single figures like Singing Boy, further demonstrate his consistent focus on candlelit interiors and the human element within them. He also reportedly collaborated on at least two drawings with Hendrick Steenwyck the Younger, a painter known for his architectural interiors, suggesting a versatility beyond his primary focus.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Adam de Coster operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic landscape. In Antwerp, while Peter Paul Rubens and his workshop represented a grand, heroic Baroque style, other artists like Jacob Jordaens and Anthony van Dyck (though Van Dyck spent much time abroad) also made significant contributions. De Coster's Caravaggist leanings placed him in a distinct, yet respected, category.

His closest stylistic parallels in the Low Countries are found among the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Gerrit van Honthorst, in particular, was famed for his candlelit scenes, earning him the nickname "Gherardo delle Notti" (Gerard of the Nights) in Italy. While both artists explored similar themes, De Coster's work often possesses a quieter, more introspective quality compared to Honthorst's sometimes more boisterous gatherings. Other Utrecht painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen also brought the Caravaggesque style north, influencing the artistic climate.

In Flanders itself, Theodore Rombouts was another contemporary who embraced Caravaggism, often depicting lively genre scenes and religious subjects with strong chiaroscuro. While their subject matter sometimes overlapped, De Coster's specialization in nocturnal effects was more pronounced.

Beyond the Low Countries, the French painter Georges de La Tour, working slightly later, also became a supreme master of candlelight scenes, particularly religious subjects imbued with a profound stillness and spiritual intensity. Though a direct link is not established, their shared fascination with the expressive power of a single flame creates an interesting parallel.

Other Dutch contemporaries, even if not strictly Caravaggisti, contributed to the era's rich artistic output. Figure painters like Frans Hals explored a vibrant realism, while still-life artists such as Pieter Claesz captured the textures and forms of everyday objects with meticulous detail. Even Rembrandt van Rijn, a master of chiaroscuro in his own right, developed his unique approach to light and shadow in this period. The art dealer Hendrick van Uylenburgh, with whom Rembrandt was associated, was a significant figure in the Amsterdam art market, facilitating connections and commissions.

The earlier Flemish painter Joos van Cleve, active in the early to mid-16th century, represents an older tradition, but the continuity of artistic production in Antwerp provided a backdrop for De Coster's innovations. Later, Godfried Schalcken (1643-1706), born the year De Coster died, would also become renowned for his exquisite small-scale candlelit scenes, carrying the tradition into the latter half of the 17th century.

The Enigma of De Coster: Attribution and Legacy

Despite his evident skill and contemporary recognition, Adam de Coster remains a somewhat shadowy figure in art history, primarily due to a scarcity of signed works and limited biographical documentation. This has led to challenges in definitively attributing works to his hand. For many years, his oeuvre was partially conflated with that of other "candlelight masters," and some works have been debated by scholars. The art historian Roberto Longhi, for instance, questioned certain attributions in the mid-20th century, a common process in the scholarly re-evaluation of artists from this period.

The term "Master of the Candlelight" has sometimes been used as a notname for an anonymous artist or group of artists working in a similar style, which can occasionally cause confusion. However, De Coster himself is unequivocally a true master of candlelight painting, and his identity is firmly established, even if the full extent of his output is still subject to scholarly refinement.

His personal life, his motivations, and the specific circumstances of his training and potential travels are not fully known. This lack of detailed information contributes to the "enigma" surrounding him, making each rediscovered or reattributed work a valuable piece in understanding his artistic personality. What is clear is his dedication to a specific type of scene, which he explored with remarkable consistency and sensitivity.

The Enduring Glow: De Coster's Influence and Modern Appreciation

Adam de Coster's contribution to Flemish Baroque art lies in his specialized and highly refined approach to nocturnal scenes. He successfully adapted the dramatic innovations of Caravaggism to create works of intimate and often tender beauty. His paintings invite quiet contemplation, drawing the viewer into a world where the flickering flame of a candle pushes back the darkness, revealing moments of human activity, emotion, and connection.

While he may not have had the wide-ranging influence of a figure like Rubens, De Coster's mastery within his chosen niche was exceptional. His ability to convey mood and psychological depth through the subtle manipulation of light and shadow set him apart. The recent high auction price for A Young Woman Holding a Distaff before a Lit Candle is a testament to the growing recognition and appreciation of his unique talent in the contemporary art market and among art historians.

His works continue to resonate because they capture something universal: the allure of the night, the intimacy of shared moments in low light, and the way a simple flame can transform an ordinary scene into something magical and profound. Adam de Coster, the "Pictor Noctium," skillfully illuminated these fleeting moments, leaving behind a legacy that glows warmly through the centuries. His paintings are not just depictions of light, but meditations on its power to reveal, conceal, and transfigure the world around us.