Trophime Bigot, a figure who for centuries remained shrouded in relative obscurity, has gradually emerged from the shadows of art history to be recognized as a significant French Baroque painter. Active during the first half of the 17th century, his work is particularly noted for its dramatic use of chiaroscuro and its intimate, often candlelit, scenes. This approach places him firmly within the Caravaggesque tradition, a pan-European movement inspired by the revolutionary Italian master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Bigot's life and oeuvre present a fascinating case study in artistic influence, regional adaptation, and the complex processes of attribution and rediscovery that characterize the study of Old Masters. His career spanned pivotal artistic centers, primarily Rome and his native Provence, and his paintings continue to engage scholars and art lovers alike with their potent blend of realism, theatricality, and spiritual depth.

Early Life and Provençal Roots

Trophime Bigot was born in Arles, in the Provence region of southern France, in 1579. Details about his early life and artistic training in France are scarce, a common challenge when researching artists from this period who did not achieve immediate, widespread fame or leave extensive personal records. It is presumed that he received his initial artistic education locally, as was customary. Arles, an ancient city with a rich Roman heritage, and the broader Provençal region, had its own artistic traditions, though it was also open to influences from Italy, given its geographical proximity and historical ties.

The artistic environment in Provence during the late 16th and early 17th centuries was active, with demand for religious paintings for churches and private chapels, as well as portraiture and other genres. However, for ambitious artists seeking to engage with the most innovative trends of the time, a journey to Italy, particularly Rome, was almost a prerequisite. It is highly probable that Bigot, like many of his contemporaries, recognized the necessity of such a pilgrimage to further his artistic development and career prospects. The exact date of his departure from France for Italy is not precisely known, but archival evidence places him in Rome by 1620.

The Roman Sojourn: Immersion in Caravaggism

Bigot's presence in Rome between approximately 1620 and 1634 marks a crucial period in his artistic formation. Rome at this time was the undisputed center of the European art world, a vibrant melting pot of artists from across the continent, all drawn by its classical heritage, the patronage of the Church and powerful families, and the groundbreaking artistic innovations that had recently taken place. The most significant of these was the work of Caravaggio (1571-1610), whose radical naturalism, dramatic use of tenebrism (the intense contrast of light and dark), and emotionally charged depictions of religious and mythological scenes had revolutionized painting.

Although Caravaggio himself had died a decade before Bigot's documented arrival, his influence was pervasive. A generation of artists, both Italian and foreign, known as the Caravaggisti, had embraced and adapted his style. Among these were Italian painters like Orazio Gentileschi and his talented daughter Artemisia Gentileschi, Bartolomeo Manfredi (whose "Manfrediana Methodus" involved depicting genre scenes of taverns, soldiers, and musicians in a Caravaggesque manner), and Jusepe de Ribera, a Spaniard who became a leading figure in Naples.

Crucially for Bigot, Rome also hosted a significant contingent of Northern European artists, particularly from Utrecht in the Netherlands. Figures like Gerrit van Honthorst (known in Italy as Gherardo delle Notti for his nocturnal scenes), Dirck van Baburen, and Hendrick ter Brugghen had spent time in Rome, absorbing Caravaggio's style and developing their own distinctive approaches, often emphasizing artificial light sources like candles and torches. When these artists returned north, they disseminated Caravaggism there. Bigot would have been exposed to this international circle, and it is within this milieu that his own artistic identity began to solidify. He is documented as living in the Via Margutta, a street popular with artists. During his Roman years, he was also known by the Italianized name "Teofili Trufemondi," a phonetic rendering of Trophime Bigot.

The "Maître à la Chandelle": An Art Historical Puzzle

For a long time, a distinct group of Caravaggesque paintings, characterized by their intimate scale, nocturnal settings, and prominent use of a single, often shielded, candle as the primary light source, were attributed to an anonymous artist dubbed the "Maître à la Chandelle" (the Candlelight Master). These works, often depicting saints in contemplation, domestic scenes, or figures in quiet interaction, shared a consistent stylistic signature: simplified forms, a limited palette often dominated by reds and browns, and a focus on the psychological presence of the figures, heightened by the dramatic play of light.

The art historian Benedict Nicolson, in the mid-20th century, undertook significant research to identify this enigmatic master. Through careful stylistic analysis and the examination of archival documents, Nicolson proposed that many of the works previously attributed to the "Candlelight Master" were, in fact, by Trophime Bigot. This reattribution was a major step in reconstructing Bigot's oeuvre and recognizing his distinct contribution to the Caravaggesque movement. However, the "Candlelight Master" designation still occasionally appears, reflecting the initial anonymity and the specific stylistic niche these works occupy. The debate also once included the possibility of a "Trophime Bigot the Younger," a son who continued in a similar style, but more recent scholarship, as indicated in the provided information, suggests that there was only one Trophime Bigot and that he had no children. The stylistic variations in his work are now generally attributed to different phases of his career or adaptations to different patronal demands.

Artistic Style and Characteristics

Trophime Bigot's style is quintessentially Caravaggesque, yet it possesses its own distinct inflections. His most recognizable trait is his mastery of tenebrism, specifically the use of candlelight to illuminate his scenes. Unlike the often harsh, raking light of Caravaggio, Bigot's candlelight tends to be softer, creating more diffused shadows and a more intimate, contemplative atmosphere. The light source itself – a candle, a lantern, or an oil lamp – is frequently visible within the composition, often partially obscured by a hand or an object, a device that enhances the sense of realism and draws the viewer into the scene.

His figures are typically rendered with a degree of simplification, eschewing excessive anatomical detail in favor of broad, sculptural forms defined by light and shadow. This simplification can lend his figures a certain monumentality, even in smaller-scale works. His palette is often restricted, favoring warm earth tones, deep reds, and browns, which contribute to the nocturnal mood.

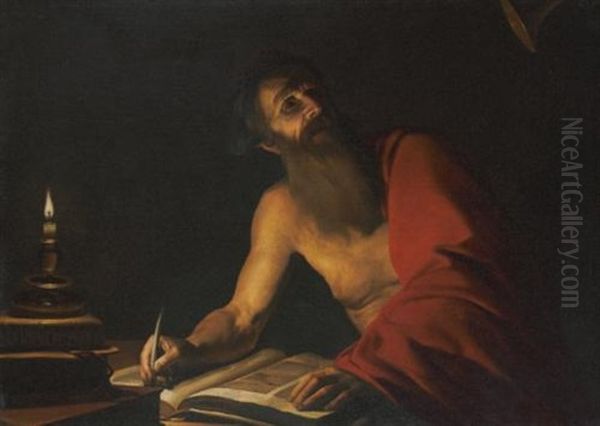

The subject matter of Bigot's "candlelight" paintings frequently involves single figures or small groups engaged in quiet activities or moments of introspection. Religious themes are common, such as saints in prayer or meditation (St. Jerome, St. Sebastian, Mary Magdalene), or scenes from the life of Christ that lend themselves to nocturnal settings, like the Denial of St. Peter. He also painted genre scenes, sometimes with allegorical or moralizing undertones, such as figures examining objects by candlelight, which could allude to themes of transience or the pursuit of knowledge.

Comparisons with Georges de La Tour (1593-1652), another French master of candlelight scenes, are inevitable. Both artists explored similar themes and lighting effects. However, de La Tour's figures often possess a more geometric abstraction and a profound stillness that can feel almost otherworldly, whereas Bigot's figures, while simplified, tend to retain a more tangible, earthy presence. While direct contact between Bigot and de La Tour is not definitively documented, their shared artistic concerns point to a common wellspring of Caravaggesque influence, possibly filtered through different channels or developed independently in response to similar artistic problems.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works are considered representative of Trophime Bigot's style and thematic concerns.

_The Assumption of the Virgin_: This altarpiece, painted after his return to France, showcases his ability to handle larger-scale religious commissions. While it may employ a broader range of light than his intimate candlelight scenes, the dramatic illumination and emotional intensity are characteristic. Such works were crucial for church decoration in the Counter-Reformation era, aiming to inspire piety and awe.

_The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence_ (or _The Flagellation of St. Lawrence_): Another significant altarpiece produced for a church in Arles, this work would have depicted the suffering of the saint with the dramatic lighting and emotional force typical of Caravaggesque art. Martyrdom scenes were popular subjects, allowing artists to explore extremes of human experience and divine faith.

_Judith Cutting Off the Head of Holofernes_: This biblical subject, famously depicted by Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, was a favorite among Caravaggesque painters for its inherent drama and violence. Bigot's version, if securely attributed (as some attributions have been questioned), would likely focus on the psychological tension of the moment, illuminated by his characteristic candlelight. The provided information notes that the attribution of a version dated c. 1640 has been debated, highlighting the ongoing scholarly work in defining his oeuvre.

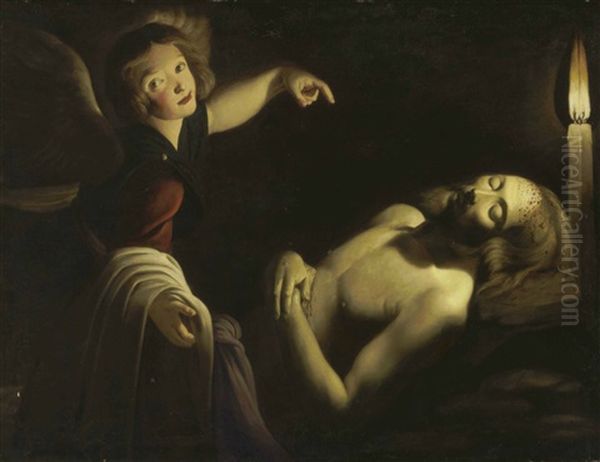

_Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene_: This subject, depicting the wounded saint being cared for by Irene, offered opportunities for pathos and the depiction of the human form under dramatic lighting. Several versions of this theme are associated with Bigot or the "Candlelight Master" corpus, emphasizing the compassionate and devotional aspects of the narrative. The questioning of its authenticity, as mentioned in the provided text, again underscores the complexities of attribution.

_A Man Examining a Coin by Candlelight_ (or similar genre scenes): These smaller, intimate works are perhaps most archetypal of the "Candlelight Master" style. They often feature a single figure, or a couple, engrossed in an activity illuminated by a single candle. Such scenes could carry vanitas connotations (the transience of worldly goods) or simply explore the captivating effects of artificial light.

_The Denial of St. Peter_: This New Testament episode, taking place at night by a fire or lamp, was a natural fit for Bigot's style. It allowed for a multi-figure composition with strong emotional content, centered on Peter's moment of weakness.

_Two Mice Gnawing a Candlewick_: If this unusual subject is indeed by Bigot, it would represent a foray into a more symbolic or allegorical still life, where the humble subject is imbued with meaning through the play of light and the potential symbolism of the mice and the diminishing candle (perhaps alluding to the passage of time or the fragility of life). Its disputed attribution reflects the challenges in defining the full range of an artist's work.

The total number of works confidently attributed to Trophime Bigot is still a matter of scholarly discussion, but the provided information suggests a figure of around 61 paintings. This makes his known output relatively modest compared to some of his more prolific contemporaries, but significant enough to establish his artistic personality.

Return to Provence and Later Career

In 1634, Trophime Bigot returned to his native Arles. His Roman experiences had evidently equipped him with a sophisticated and sought-after style. He received commissions for important altarpieces, including the aforementioned Assumption of the Virgin and The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence for local churches. These larger works demonstrate his ability to adapt his Caravaggesque style, with its emphasis on dramatic lighting and emotional realism, to the demands of public religious art.

From 1638 to 1642, Bigot resided in Aix-en-Provence, another important cultural center in the region. Here, he continued to work, likely producing more altarpieces and possibly paintings for private patrons. The provided information mentions a collaboration in 1638 with a painter named François Gaillard on a mural for the Church of Notre-Dame-la-Principale in Arles, indicating his engagement with the local artistic community.

After his time in Aix, Bigot returned to Arles. His final years were spent in Avignon, a city with a rich papal history and a vibrant artistic scene. He died in Avignon on February 21, 1650, and was buried in the Church of St. Peter. His career thus came full circle, beginning and ending in his native Provence, but profoundly shaped by his formative years in Rome.

Interactions and Influences: Bigot and His Contemporaries

Trophime Bigot's artistic journey was interwoven with the broader currents of early 17th-century European art.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio: The foundational influence. Though Bigot likely never met him, Caravaggio's works in Rome provided the primary stylistic template.

Utrecht Caravaggisti: Gerrit van Honthorst, in particular, is a key figure for comparison due to his own specialization in candlelight scenes. While direct personal contact in Rome is speculative, their shared thematic and stylistic concerns are undeniable. Matthias Stom (or Stomer), another Northerner active in Italy, also produced powerful nocturnal scenes and could have been part of the same artistic circles. Hendrick ter Brugghen is another important Utrecht Caravaggist whose work Bigot might have known.

Georges de La Tour: The most famous French exponent of candlelight painting. As discussed, the relationship is one of stylistic affinity rather than documented direct influence, though both artists were working within a similar Caravaggesque framework.

Other French Caravaggisti: Artists like Valentin de Boulogne, Simon Vouet (during his early Roman period), Nicolas Régnier, and Claude Vignon were also part of the French contingent in Rome absorbing and reinterpreting Caravaggio's lessons. Bigot would have been aware of their work. Jacques Blanchard, another French contemporary, also worked in a Caravaggesque vein.

Italian Caravaggisti: Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia Gentileschi, Bartolomeo Manfredi, and Jusepe de Ribera were prominent figures whose interpretations of Caravaggism contributed to the artistic ferment in Rome and Naples.

Provençal Contemporaries: In Provence, Bigot would have interacted with local artists. The documented collaboration with François Gaillard is one example. The artistic landscape of Provence would have included painters working in more traditional styles as well as those, like Bigot, who brought back international trends. The reference to a "Jacques" (possibly Jacques de l'Estre or another local painter) whose works might have been confused with Bigot's points to a shared regional stylistic vocabulary or level of quality that could lead to attributional complexities.

The extent of Bigot's direct personal interactions with many of these figures is often difficult to ascertain precisely from historical records. However, the artistic environment of Rome, in particular, was one of intense exchange and emulation, and it is certain that he was aware of and responded to the work of many leading contemporaries.

Controversies and Scholarly Debates

Trophime Bigot's rediscovery and the reconstruction of his oeuvre have been accompanied by several art historical debates:

1. The "Candlelight Master" Identity: The primary debate revolved around whether the corpus of "Candlelight Master" paintings could be securely attributed to Trophime Bigot. While Nicolson's thesis is widely accepted for many of these works, the precise boundaries of Bigot's oeuvre and the "Candlelight Master" group remain subjects of ongoing refinement.

2. The "Two Bigots" Theory: The notion of a Trophime Bigot "the Elder" and "the Younger" (father and son) was proposed to account for stylistic variations or a perceived extended period of activity for the "Candlelight Master." However, as noted, recent scholarship leans strongly towards a single Trophime Bigot, with stylistic differences explained by career development or differing commissions.

3. Attribution of Specific Works: As seen with Judith Cutting Off the Head of Holofernes, Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene, and Two Mice Gnawing a Candlewick, the attribution of individual paintings to Bigot can still be debated. This is common for artists whose oeuvres have been reconstructed relatively recently and for whom contemporary documentation is not exhaustive. Stylistic analysis, technical examination, and provenance research all play roles in these ongoing discussions.

4. Distinguishing Bigot from Contemporaries: The similarity of his candlelight scenes to those of Georges de La Tour, and to a lesser extent, some works by Honthorst or Stom, can create attributional challenges, especially for undocumented works.

5. Variations in Style: The differences between Bigot's more intimate, Roman-period candlelight works and his larger-scale Provençal altarpieces initially raised questions. It is now generally understood that artists often adapted their style to the scale, function, and patronal expectations of different types of commissions.

These debates are typical of the scholarly process in art history, where new evidence and interpretations continually refine our understanding of artists and their works.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Despite the quality and distinctiveness of his work, Trophime Bigot did not achieve the lasting fame of some of his contemporaries, like Georges de La Tour or the major Italian and Dutch Caravaggisti, during the centuries following his death. His name faded into relative obscurity, and his works were often misattributed or grouped anonymously.

His "rediscovery" in the 20th century, largely thanks to the efforts of scholars like Benedict Nicolson, has restored him to his rightful place as a notable figure in French Baroque painting and an important participant in the international Caravaggesque movement. His paintings are now found in various museums and private collections. The provided information lists institutions such as the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, the Vatican Museums, Bob Jones University in South Carolina, and the Portland Art Museum in Oregon as holding his works. An altarpiece is also noted in St. Peter's Church, Padua. The appearance of works like An Angel Watching Over the Dead Christ at auction (Sotheby's, January 2023) indicates ongoing market interest and potential for further discoveries or reattributions. A work titled Candlelight Master, described as a self-portrait dated 1672 and owned by James Murchamy in Dublin, is intriguing; the late date (22 years after Bigot's death) suggests it might be a copy, a work by a follower, or a misdated/misattributed piece, highlighting the complexities that can still surround his legacy.

Bigot's legacy lies in his sensitive and evocative use of candlelight to create scenes of profound intimacy and psychological depth. His best works draw the viewer into a hushed, contemplative world, where the flickering flame illuminates not just faces and forms, but also inner states of being. He represents a distinct French voice within the broader Caravaggesque phenomenon, one that favored quiet introspection over overt theatricality, even while employing the dramatic tools of tenebrism.

Conclusion

Trophime Bigot stands as a testament to the rich and varied artistic landscape of 17th-century Europe. From his beginnings in Arles to his formative years in the bustling artistic hub of Rome, and his mature career back in Provence, he absorbed and reinterpreted one of the most powerful artistic currents of his time – Caravaggism. His particular genius lay in his exploitation of artificial light, especially candlelight, to craft scenes of quiet intensity and emotional resonance. While the "Candlelight Master" may once have been an enigma, the scholarly efforts of the past century have largely given this master a name and a history. Trophime Bigot's paintings, with their warm, enveloping shadows and softly glowing figures, continue to captivate, offering a unique window into the spiritual and everyday life of the Baroque era. His contribution enriches our understanding of French art and the enduring appeal of light and shadow in painting.