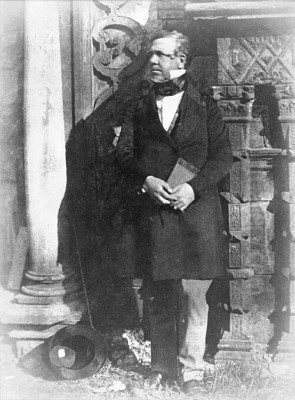

David Roberts stands as one of the most significant figures in 19th-century British art, a painter whose life journey took him from the humble beginnings of a Scottish house painter's apprentice to the esteemed halls of the Royal Academy in London. Born in 1796 and passing away in 1864, Roberts carved a unique niche for himself, primarily celebrated for his meticulous and evocative depictions of the Near East. His work, bridging the gap between topographical accuracy and Romantic sensibility, not only captured the imagination of the Victorian public but also provided an invaluable visual record of landscapes and monuments, many of which have since changed or vanished. His transition from the ephemeral world of theatrical scene painting to becoming a renowned easel painter and printmaker exemplifies a remarkable artistic trajectory fueled by talent, ambition, and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

David Roberts was born on October 24, 1796, in Stockbridge, then a village on the outskirts of Edinburgh, Scotland. His family background was modest; his father, John Roberts, was a shoemaker. Despite the lack of artistic connections in his immediate family, young David displayed a clear aptitude for drawing from an early age. Recognizing his potential, his mother encouraged his artistic inclinations, famously allowing him to practice sketching on the whitewashed walls of their home. This early encouragement proved crucial in nurturing his nascent talent.

Formal artistic training in the academic sense was not readily available given his family's circumstances. However, practical training was. At the age of ten, following the advice of the headmaster at the Edinburgh Trustees' Academy (though he did not formally attend as a student then), Roberts was apprenticed to Gavin Beugo, a local house painter and decorator. This seven-year apprenticeship, while demanding and focused on trade skills rather than fine art, provided Roberts with invaluable foundational knowledge. He learned about pigments, perspective, decorative techniques, and the handling of brushes on a large scale – skills that would unexpectedly serve him well in his later career, first in theatre and then in his large-scale canvases. During his apprenticeship, Roberts dedicated his spare time to sketching and studying art independently, demonstrating a commitment that belied his youth.

The World of Theatrical Scene Painting

Upon completing his apprenticeship around 1815, Roberts initially found work as a house painter. However, his artistic ambitions soon led him towards the more creative field of theatrical scene painting. He began working for James Bannister's circus, decorating their travelling shows. This was followed by engagements at the Pantheon Theatre in Edinburgh, and then more significantly, at the Theatre Royal in Glasgow in 1819, and subsequently the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh. Scene painting in this era was a demanding craft, requiring artists to create vast, illusionistic backdrops quickly and effectively, often depicting grand architectural settings or dramatic landscapes.

This period was formative. It honed Roberts' skills in rapid execution, perspective, and creating dramatic effects with light and shadow on a monumental scale. It also exposed him to a wide range of architectural styles and landscape types, albeit often filtered through the romanticized lens of theatrical convention. In 1820, while working in Edinburgh, he met Clarkson Stanfield, another aspiring artist who was also employed as a scene painter at the Theatre Royal. Stanfield, who would also achieve great fame as a marine and landscape painter, became a lifelong friend and a significant influence. It was Stanfield who encouraged Roberts to pursue fine art alongside his theatrical work and submit paintings for exhibition. The collaborative and sometimes competitive environment of the theatre paint room undoubtedly spurred both artists on. Their work, alongside earlier innovators like Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, elevated scene painting to a respected art form in its own right during this period.

Transition to Fine Art and London Success

Encouraged by Stanfield and driven by his own ambition, Roberts began to produce easel paintings, primarily architectural subjects and landscapes, alongside his theatre work. He first exhibited in Edinburgh, showing three paintings at the Exhibition of Works by Living Artists in 1821. Seeking greater opportunities, Roberts moved to London in 1822. Initially, he continued to work primarily as a scene painter, securing prestigious positions at the Coburg Theatre (now the Old Vic) and later at the renowned Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where he worked alongside Stanfield. Their spectacular sets were highly acclaimed and drew large audiences.

However, Roberts increasingly focused on establishing himself as a fine artist. He began exhibiting his oil paintings and watercolors in London galleries. In 1823, he exhibited for the first time at the Society of British Artists (SBA), an organization founded as an alternative to the Royal Academy. He became a member shortly after and was a frequent exhibitor, eventually serving as its president in 1831. His works, often depicting British and Continental architectural views, gained positive critical attention. This success gradually allowed him to reduce his commitments to the theatre, and by 1830, he had largely given up scene painting to dedicate himself fully to his career as an independent artist. This marked a significant shift, moving away from the collaborative, often anonymous work of the theatre towards the individual recognition sought by easel painters like the dominant figures of the day, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable.

Early Travels and Picturesque Views

Travel became central to Roberts' artistic practice early in his career. Like many artists of his time, he sought fresh subjects and inspiration beyond the British Isles. In 1824, he made his first significant trip abroad, visiting Normandy. The sketches he brought back resulted in paintings exhibited at the SBA, depicting picturesque French architecture, such as views of Rouen Cathedral. These early trips confirmed his fascination with historical buildings and atmospheric locations.

A more extensive and influential journey followed in 1832-1833, when Roberts travelled through Spain and, briefly, to Tangier in Morocco. Spain, relatively less frequented by British artists compared to Italy or France at the time, offered a wealth of visually rich subjects, particularly the legacy of Moorish architecture in Andalusia. This trip was immensely productive. Roberts filled sketchbooks with drawings of cities like Seville, Granada (including the Alhambra), Cordoba, and Burgos. The resulting works captured the unique blend of European and Islamic influences in Spanish architecture and the dramatic landscapes. This journey led to the publication of his first major lithographic series, Picturesque Sketches in Spain (1837), which proved highly popular and cemented his reputation as a skilled topographical artist with a flair for the picturesque. His Spanish tour coincided with a growing interest in the country, partly fueled by writers like Washington Irving, whose Tales of the Alhambra appeared in 1832. Roberts' work resonated with this burgeoning fascination, shared by fellow artists like John Frederick Lewis, who also spent considerable time in Spain.

The Grand Tour: A Pivotal Journey to the Near East

Roberts' travels in Spain whetted his appetite for more exotic locales. The ultimate goal became a journey to the Near East – Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and the surrounding regions. This was an ambitious undertaking in the 1830s. Travel was arduous and potentially dangerous, and the region was relatively unknown to the European public beyond biblical narratives and classical texts. Roberts was motivated by a desire to see and record firsthand the sites associated with the Bible and ancient history, as well as the magnificent Islamic architecture. He was also undoubtedly aware of the growing public fascination with 'Oriental' subjects, a trend known as Orientalism, which was sweeping across European arts and culture.

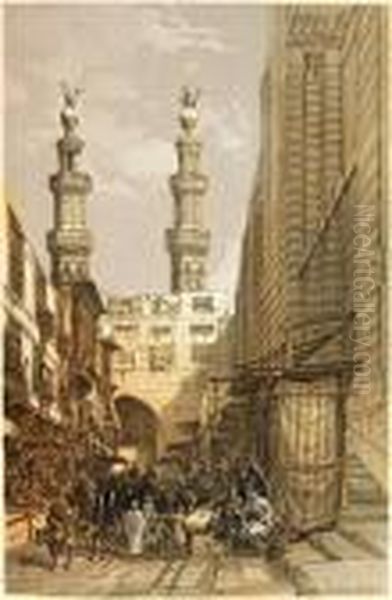

He embarked on this career-defining journey in August 1838, sailing first to Alexandria, Egypt. Over the next eleven months, he travelled extensively. In Egypt, he sailed up the Nile deep into Nubia, reaching the temples of Abu Simbel, sketching ancient monuments like Karnak, Luxor, Philae, and the Pyramids of Giza. He spent considerable time in Cairo, where, remarkably, he obtained permission from the modernizing ruler, Muhammad Ali Pasha, to sketch inside mosques – a privilege rarely granted to non-Muslims at the time. Roberts meticulously documented the intricate details of Islamic architecture, interiors, and street scenes. His use of pig bristle brushes within these sacred spaces was a potentially controversial detail he navigated carefully.

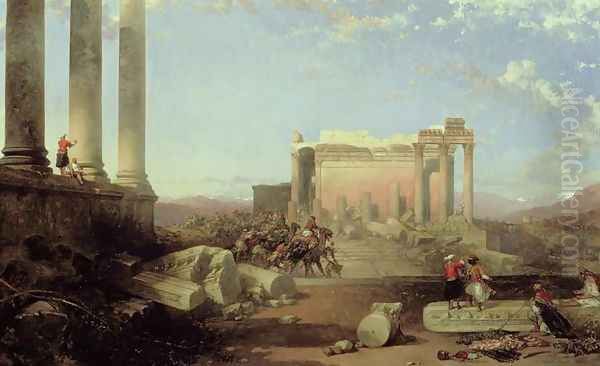

From Egypt, Roberts crossed the Sinai desert via camel caravan, enduring harsh conditions, including an attack by Bedouins and suffering from ophthalmia (a severe eye inflammation). He visited the Monastery of Saint Catherine and travelled through Petra in modern-day Jordan, capturing its famous rock-cut tombs. He then journeyed through the Holy Land (Palestine), visiting Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, and sites around the Sea of Galilee. His travels continued north into Lebanon, where he sketched the colossal Roman ruins at Baalbek, before finally sailing back from Alexandria in July 1839, returning to London in 1840. Throughout this epic journey, he produced hundreds of detailed sketches and watercolors, forming the raw material for his most famous works. His approach differed from earlier artists like Luigi Mayer, aiming for greater topographical accuracy while still imbuing his scenes with a sense of Romantic grandeur.

The Holy Land and Egypt & Nubia: A Publishing Phenomenon

Upon his return to London, Roberts faced the task of transforming his vast collection of sketches into a form suitable for publication. He partnered with the publisher Francis Graham Moon and the highly skilled Belgian lithographer Louis Haghe. Haghe translated Roberts' watercolors and drawings onto lithographic stones with exceptional fidelity, capturing the subtle tones and intricate details. The resulting prints were then often hand-colored by teams of colorists, adding vibrancy and richness.

The work was published by subscription in parts between 1842 and 1849, under the monumental title The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt & Nubia. It comprised a total of 247 lithographs, issued in two major series: The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia (1842-1849) and Egypt & Nubia (1846-1849). The publication was an unprecedented success, both commercially and critically. It offered the British public, hungry for knowledge of these distant lands, a vivid and seemingly authoritative window onto the landscapes, ancient ruins, and sacred sites of the Near East. The scale, quality, and perceived accuracy of the images were widely praised. Roberts' work became the definitive visual representation of the region for generations and remains an invaluable historical record. It significantly shaped European perceptions of the Middle East and became a cornerstone of Orientalist art.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Vision

David Roberts' artistic style is characterized by a unique blend of topographical accuracy and Romantic sensibility. While he aimed for faithful representations of architecture and landscapes, his work is rarely just a dry record. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the 'genius loci' or spirit of place. His compositions are often dramatic, employing strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to emphasize architectural forms and create atmosphere. He frequently included small human figures in his scenes, not just as anecdotal detail, but crucially to convey the immense scale of the monuments and landscapes he depicted, enhancing the sense of the sublime.

His training as a scene painter likely influenced his compositional choices and his handling of light to create dramatic effect. His attention to architectural detail was meticulous, earning him praise for accuracy, although scholars note he sometimes took artistic liberties for compositional effect, slightly altering perspectives or combining elements. His color palette was rich and harmonious, particularly in his oil paintings and the hand-colored lithographs. He was equally proficient in oil and watercolor, using the latter primarily for his on-site sketches and preparatory studies, which possess a freshness and immediacy. His detailed, structured style can be compared to contemporaries known for architectural views, such as Samuel Prout, but Roberts brought a grander scale and a more profound sense of historical weight to his subjects, distinguishing him from the more purely picturesque approach of many topographical artists. His work stands in contrast to the more atmospheric and light-obsessed landscapes of his great contemporary, J.M.W. Turner.

Roberts and the Royal Academy

Roberts' growing reputation and the success of his travels and publications led to recognition from the highest echelon of the British art establishment, the Royal Academy of Arts. He had begun exhibiting there occasionally while still primarily associated with the SBA. Following his return from the Near East, his profile soared. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1838, even before the full publication of The Holy Land began, and achieved the status of full Royal Academician (RA) in 1841.

Election to the RA cemented Roberts' position as one of Britain's leading artists. He became a regular and prominent exhibitor at the Academy's annual Summer Exhibitions, showcasing large-scale oil paintings based on his travels, alongside views of European and British subjects. His works were generally well-received by critics and popular with the public and collectors. He joined the ranks of other esteemed Academicians of the era, such as the aforementioned Turner, Stanfield, and Landseer, as well as narrative painters like William Powell Frith and historical/biblical painters like John Martin, contributing his unique focus on architectural and topographical subjects to the diverse landscape of Victorian art.

Later Works and Continued Travels

While the Near East tour and its resulting publications represent the pinnacle of Roberts' fame, he remained a prolific artist throughout his later career. He continued to travel, albeit less extensively than before. He made several trips to the Continent, revisiting France, Belgium (painting views in Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp), Austria, and notably Italy, where he painted popular views of Venice and Rome. These works, while perhaps lacking the groundbreaking novelty of his Eastern subjects, were still highly accomplished and commercially successful.

He also continued to paint British subjects, including views of London. One notable series depicted the dramatic fire that destroyed the Houses of Parliament in 1834, a subject also famously tackled by J.M.W. Turner. Roberts produced views of the exterior during the blaze and the interior ruins afterwards. He also painted Scottish landscapes and architectural subjects, maintaining a connection to his homeland. His later works generally maintained the detailed style and compositional sense developed earlier in his career. He remained an active participant in the London art world, respected for his professionalism and his impressive body of work. Other artists exploring topographical and Orientalist themes during this later period included Edward Lear and the German-born Carl Haag, who also found success in London.

Later Life, Legacy, and Influence

David Roberts enjoyed considerable financial success and critical acclaim throughout much of his career. He lived comfortably in London, maintaining a studio first in Abingdon Street and later at 7 Fitzroy Street. Despite his London success, he never forgot his Scottish roots and maintained friendships and connections there. He was known for his amiable personality and professionalism. Sources also mention his charitable nature and support for fellow artists.

He continued painting actively into his later years. His death came suddenly on November 25, 1864. He collapsed from an apoplectic fit (a stroke) while walking on Berners Street in London and died later that evening. He was 68 years old. He was buried in West Norwood Cemetery in London, a site noted for its Victorian funerary monuments.

David Roberts' legacy is substantial. His most enduring contribution lies in the vast body of work documenting the architecture and landscapes of the Near East. The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt & Nubia remains a landmark publication, valued not only for its artistic merit but also as a crucial historical record of sites before the advent of widespread photography and modern development. His paintings and prints shaped Western perceptions of the region for decades and are key works within the genre of Orientalism. His works are held in major public collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum in London, the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and many others, ensuring his continued visibility and relevance. He stands as a testament to talent, perseverance, and the power of art to transport viewers across time and geography.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

David Roberts' career trajectory, from decorator's apprentice to celebrated Royal Academician, is a remarkable story of artistic dedication and ambition. His early work in theatre provided him with a unique skill set that he masterfully adapted to easel painting and printmaking. His extensive travels, particularly the arduous but immensely fruitful journey through the Near East, resulted in his magnum opus – a series of lithographs that captivated the Victorian imagination and provided an unparalleled visual encyclopedia of the region's monuments and landscapes. Combining meticulous detail with a Romantic sense of grandeur and atmosphere, Roberts created images that were both informative and deeply evocative. He not only documented the world but interpreted it, leaving behind a legacy that continues to fascinate scholars, collectors, and the public alike, securing his place as a pivotal figure in the history of British art and topographical illustration.