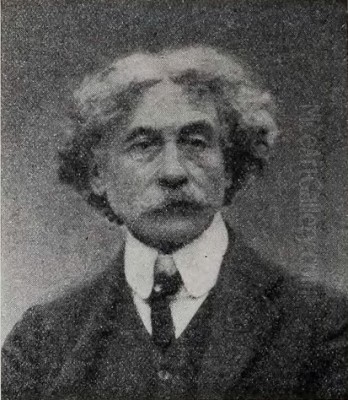

Raffaele Ragione stands as a fascinating figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art. Born in the vibrant cultural hub of Naples in 1851 and passing away in the same city in 1925, his artistic journey navigated the currents of Realism and Impressionism. He is particularly celebrated for his sensitive portrayals of everyday life, intimate family moments, and elegant scenes captured during his significant period in Paris. His work offers a unique blend of Neapolitan artistic traditions and the revolutionary techniques emerging from the French capital.

Ragione's career reflects a dedication to observing the world around him, translating fleeting moments and social nuances onto canvas. From his early training in Naples to his mature works created in Paris, he demonstrated a keen eye for detail, a subtle understanding of human emotion, and a developing mastery of light and color. His legacy lies in his ability to capture the spirit of his time, whether depicting the bustling life of Naples or the refined leisure of Parisian society.

Neapolitan Roots and Artistic Formation

Raffaele Ragione's artistic journey began in Naples, a city with a rich and distinct artistic heritage. He enrolled at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli (Naples Academy of Fine Arts), a crucial institution for aspiring artists in Southern Italy. Here, he received formal training under the guidance of influential masters who shaped the Neapolitan art scene.

His most notable teachers were Domenico Morelli and Stanislao Lista. Morelli was a leading figure in 19th-century Italian painting, known for his historical and religious subjects rendered with dramatic realism and emotional intensity. Lista, a sculptor and teacher, emphasized drawing and form. Studying under these prominent figures provided Ragione with a solid foundation in academic techniques, drawing, composition, and the prevailing realist aesthetics of the time.

Beyond the Academy, the artistic environment of Naples was dynamic. The city was home to movements like the School of Posillipo, known for landscape painting, and the later Resina School (Scuola di Resina), with which Ragione is sometimes associated. This group, active near Naples, focused on capturing the unvarnished reality of local life and landscapes, often working outdoors to study light effects directly, prefiguring some aspects of Impressionism. Artists like Filippo Palizzi and Giuseppe De Nittis (before his move to Paris) were key figures in this milieu, emphasizing truthfulness to nature and everyday subjects.

This Neapolitan context profoundly influenced Ragione's early development. He absorbed the emphasis on careful observation, realistic depiction, and an interest in genre scenes – themes that would remain central throughout his career, even as his style evolved. His training instilled a respect for craftsmanship alongside an awareness of contemporary artistic trends focused on modern life.

Early Career and Realist Depictions

Emerging from his academic training, Raffaele Ragione began to establish his presence in the Neapolitan art world. Starting in 1873, he became a regular participant in the annual exhibitions organized by the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti di Napoli (Naples Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts). These exhibitions were vital platforms for artists to showcase their work and gain recognition.

His early works firmly belonged to the Realist tradition prevalent in Naples. He focused on genre scenes, capturing moments from the daily lives of ordinary Neapolitans. These paintings were characterized by meticulous attention to detail, accurate rendering of figures and settings, and a narrative quality. He demonstrated a sharp eye for social observation, depicting activities, interactions, and environments with authenticity.

Among his notable early works exhibited at the Promotrice were Carrozza di rimessa (Improved Carriage or Hired Carriage) shown in 1873, and Il racconto della nonna (Grandmother's Story) displayed in 1877. These titles suggest scenes rooted in everyday experiences and family life. Il racconto della nonna, in particular, points towards the intimate, domestic themes that would continue to interest him. His painting Comunicandosi (Communing or Receiving Communion), now held by the Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli, likely dates from this period and reflects the blend of genre and potentially religious or social commentary common at the time.

During these formative years, Ragione honed his skills in capturing textures, expressions, and the specific atmosphere of Neapolitan life. His palette, while likely more subdued than his later work, would have been focused on achieving a truthful representation of light and form. He was building a reputation as a skilled observer of the human condition within his local environment, following in the footsteps of Neapolitan realists like Gioacchino Toma, known for his poignant depictions of domestic life and social issues.

The Parisian Experience: New Influences and Collaborations

Around the turn of the century, specifically documented as 1902, Raffaele Ragione made a significant life change: he moved to Paris. The reasons cited often mention "family problems," suggesting personal circumstances prompted this relocation from Naples. Paris, at this time, was undeniably the epicenter of the art world, a crucible of innovation and home to the burgeoning Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements.

This move exposed Ragione to a radically different artistic environment. He encountered firsthand the works of French Impressionists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot. Their revolutionary approach to painting – emphasizing capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, using broken brushwork and a brighter palette – must have made a profound impact.

Sources indicate that during his time in Paris, Ragione associated and possibly collaborated with other artists. Notably mentioned are fellow Italian painters Antonio Mancini and Federico Ricci (or another artist named Ricci). Mancini, known for his highly textured, psychologically intense portraits, also spent time in Paris and was admired for his technical virtuosity. Collaborating or simply interacting with such figures would have provided Ragione with artistic exchange and support within the expatriate Italian artist community. Giuseppe De Nittis and Giovanni Boldini were other successful Italians who had already made their mark in Paris, depicting the elegant modern life of the city.

Living and working in Paris pushed Ragione's art in a new direction. While retaining his interest in everyday life and human subjects, he began to absorb the techniques and aesthetic principles of Impressionism. The city itself, with its parks, boulevards, and fashionable society, offered new subjects perfectly suited to this evolving style. His Neapolitan grounding in realism provided a base upon which the lighter, more spontaneous approach of Impressionism could be built.

Embracing Impressionism: Parisian Parks and Modern Life

Raffaele Ragione's Parisian period marked a distinct shift towards an Impressionist style. Inspired by the French masters and the vibrant atmosphere of the city, his work became lighter, brighter, and more focused on capturing the ephemeral qualities of light and movement. His brushwork grew looser and more spontaneous, moving away from the tight rendering of his earlier Neapolitan realism.

His favored subjects in Paris were the city's elegant parks and gardens, particularly the Parc Monceau. These locations provided ideal settings for exploring Impressionist concerns. He frequently depicted scenes of leisure and daily life within these green spaces: elegantly dressed women strolling or resting, nursemaids watching over children, and the play of sunlight filtering through leaves. These works capture the refined atmosphere of Belle Époque Paris.

A recurring and celebrated theme in his Parisian works is the relationship between mothers and children. Paintings often titled Bimbi al Parc Monceau (Children at Parc Monceau) or similar variations showcase tender interactions set against the backdrop of the park. These works are noted for their delicate color harmonies, sensitivity to the nuances of light, and ability to convey warmth and intimacy. One such work, Ladies Embroidering at Parc Monceau, fetched a price at Gregory's auction house, indicating continued market interest in these Parisian scenes.

His painting Amor materno (Maternal Love), likely from this period or influenced by his Parisian experiences, further underscores his focus on familial bonds, perhaps reflecting a personal longing or observation heightened by his time away from Naples. While adopting Impressionist techniques, Ragione often retained a degree of solidity in his figures, perhaps a lingering influence from his academic training, distinguishing his style slightly from some of his French contemporaries like Renoir or Morisot, who might dissolve form more completely into light and color.

His Parisian works were exhibited both in France and Italy, bringing him wider recognition. They showcased his successful adaptation to the prevailing modern style while maintaining his unique focus on intimate human moments. He captured the elegance and charm of Parisian life with a sensitivity possibly informed by his Italian roots, creating a distinctive blend of observation and painterly freedom. His depictions of Parisian life bear comparison, in subject matter if not always in style, to contemporaries like Jean Béraud or even, in their focus on modern social settings, aspects of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's world, though Ragione's tone was generally gentler and less focused on the underbelly of society.

Themes of Domesticity, Leisure, and Observation

Throughout his career, certain themes remained constant in Raffaele Ragione's work, evolving in style but consistent in focus. Central among these was the depiction of everyday life, particularly scenes of domesticity and leisure. From the Grandmother's Story in his early Neapolitan period to the mothers and children in Parc Monceau during his Parisian years, he consistently turned his attention to the intimate moments that define human experience.

His Neapolitan works often grounded these themes in the specific social context of Southern Italy, perhaps with a narrative or anecdotal quality typical of 19th-century genre painting. The focus was on realistic portrayal, capturing the details of interiors, clothing, and interactions that spoke of a particular way of life. Works like La famiglia dell'artista (The Artist's Family), held in a private collection, likely exemplify this intimate focus applied to his own circle.

In Paris, the theme of leisure took on a more elegant, cosmopolitan air. His paintings of women and children in parks reflect the fashionable side of modern urban life. Here, the emphasis shifted from detailed narrative to capturing atmosphere, light, and the fleeting gestures of figures enjoying moments of relaxation. The elegance of Parisian women, their fashion, and their graceful presence became a key subject, rendered with the lighter touch of his acquired Impressionist style.

Underlying all these themes was Ragione's keen sense of observation. Whether depicting a Neapolitan grandmother or a Parisian mother, he showed a sensitivity to human relationships and emotions. His work avoids grand historical or mythological subjects, preferring the quiet dignity and simple beauty found in ordinary life. This focus aligns him with the broader Realist and Impressionist interest in modernity and the lives of contemporary people.

His ability to adapt his style – from the detailed Realism learned under Morelli and Lista to the light-filled Impressionism embraced in Paris – while maintaining his core thematic interests demonstrates his versatility and responsiveness to the changing artistic landscape of his time. He remained, fundamentally, an observer and chronicler of the human condition in its everyday manifestations.

Later Years, Return to Naples, and Legacy

After a productive period in Paris where he absorbed and adapted Impressionist techniques, Raffaele Ragione eventually returned to his native Naples in 1923. He spent the last two years of his life back in the city where his artistic journey had begun. Information about major works or exhibitions from this very brief final period is scarce, but it marked the closing chapter of a career that had bridged two major European art centers.

Interestingly, some accounts suggest that Ragione, like other Southern Italian artists of his time, experienced periods of being overlooked or critically neglected, possibly due to prevailing biases within the Italian art establishment that sometimes favored artists from the North or Center. However, these accounts also note a rediscovery or renewed appreciation of his work, particularly later in his life or posthumously. This pattern highlights the complex dynamics of reputation and recognition within the art world.

His legacy rests on his skillful navigation between the Neapolitan Realist tradition and Parisian Impressionism. He was not merely an imitator; he synthesized these influences into a personal style characterized by sensitivity, refined color sense, and a focus on intimate human moments. His depictions of Neapolitan life offer valuable insights into the social fabric of the city, while his Parisian scenes capture the elegance and light of the Belle Époque with a distinctive charm.

Raffaele Ragione's works are represented in collections such as the Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli (Comunicandosi) and appear in private collections and occasionally at auction, like the aforementioned Ladies Embroidering at Parc Monceau. His contribution is significant within the context of Italian Ottocento (19th-century) painting, particularly among those artists who engaged with international trends while retaining a connection to their regional roots. He stands alongside figures who explored modern life, comparable in thematic interests, if distinct in style, to members of the Macchiaioli group like Telemaco Signorini or Giovanni Fattori, who also focused on contemporary Italian reality, or later artists like Gaetano Previati who explored Symbolism and Divisionism.

Some sources also attribute authorship of books on art history to him, specifically mentioning titles like Il Settecento italiano (The Italian Eighteenth Century) and La Scuola napoletana di pittura (The Neapolitan School of Painting), published in Naples. If accurate, this suggests a scholarly dimension to his engagement with art, although this aspect of his career is less documented than his painting.

Conclusion: Bridging Worlds

Raffaele Ragione's life and art exemplify the rich cultural exchange that characterized European art at the turn of the 20th century. Rooted in the strong realist traditions of Naples under masters like Domenico Morelli, he evolved significantly through his exposure to the revolutionary atmosphere of Paris and the techniques of Impressionism. He successfully integrated these influences, creating a body of work that speaks with a distinct voice.

His paintings, whether depicting the sun-drenched streets and intimate interiors of Naples or the elegant leisure of Parisian parks, consistently reveal a deep empathy for his subjects and a refined sensitivity to light and color. He excelled at capturing the quiet moments of everyday life, particularly the tender bonds within families and the graceful presence of women and children. His journey from Neapolitan Realism to a personalized form of Impressionism showcases his adaptability and artistic intelligence.

Though perhaps overshadowed at times by more famous contemporaries, Raffaele Ragione remains an important figure for understanding the transition in Italian art during this period. His work provides a valuable link between the academic traditions of the 19th century and the modern sensibilities emerging in centers like Paris. He chronicled his times with honesty and charm, leaving behind a legacy of paintings that continue to resonate with their quiet beauty and insightful observation of the human condition. His art stands as a testament to a career spent observing, interpreting, and gracefully rendering the world around him.