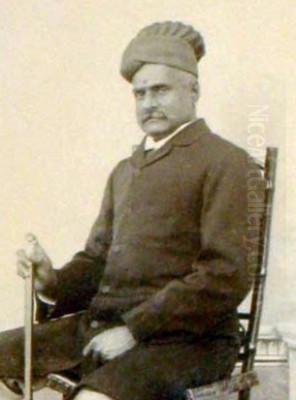

Introduction: A Bridge Between Worlds

Raja Ravi Varma stands as a colossus in the annals of Indian art history. Born during a period of significant cultural and political transition in colonial India, he emerged as a pioneering figure who masterfully bridged the gap between traditional Indian aesthetics and European academic art techniques. Often hailed as the "Father of Modern Indian Art," Varma's work not only revolutionized the visual landscape of the subcontinent but also played a crucial role in shaping a nascent national identity. His paintings, particularly those depicting scenes from Hindu epics and mythology, became ubiquitous, entering homes across the social spectrum and leaving an indelible mark on the collective Indian imagination. This article delves into the life, art, controversies, and lasting impact of this remarkable artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Travancore

Raja Ravi Varma was born on April 29, 1848, into the aristocratic Koil Thampuran family at the Kilimanoor Palace in the princely state of Travancore (present-day Kerala). His lineage connected him closely to the Travancore royal family, affording him privileges and exposure uncommon for aspiring artists of the time. His innate talent for drawing manifested early; anecdotes tell of a young Varma sketching animals and scenes on the palace walls using charcoal, much to the initial chagrin, but eventual recognition, of his elders.

His uncle, Raja Raja Varma (not to be confused with his brother, C. Raja Raja Varma), himself a painter trained in the traditional Tanjore style of art, recognized the boy's prodigious talent. He provided Ravi Varma with rudimentary training, introducing him to the indigenous art forms. The palace environment itself was a crucible of culture, where Varma could observe courtly life, rituals, and the visiting artists and dignitaries, all of which would subtly inform his later work. This early exposure within a supportive, artistically inclined family laid the foundation for his future trajectory.

The European Influence and Mastery of Oil Painting

While Varma initially learned traditional Indian painting techniques, a pivotal moment in his artistic development came with the arrival of European art practices in Travancore. He was largely self-taught in the Western style initially, meticulously studying European paintings available at the court. A significant breakthrough occurred around 1868 when the Dutch portrait painter Theodore Jensen visited Travancore on commission. Although court etiquette reportedly prevented Jensen from directly tutoring Varma, the young Indian artist keenly observed Jensen at work, absorbing the nuances of the oil medium, canvas preparation, and the European academic approach to realism, particularly in portraiture.

Varma's determination to master this new medium was immense. He experimented relentlessly, learning the complexities of mixing oil paints, achieving realistic textures, and understanding the play of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) – techniques largely absent in traditional Indian flat-perspective painting. He also reportedly received some guidance in watercolor techniques from Ramaswamy Naicker of Madurai. This adoption of oil on canvas, combined with European realism, marked a radical departure and equipped him with a powerful new visual language.

A Unique Artistic Vision: Blending East and West

Raja Ravi Varma's genius lay not merely in mastering European techniques but in applying them to intrinsically Indian subjects. He forged a unique syncretic style, often described as "Symbolic Realism" or belonging to the "Anglo-Indian" school. He employed the academic realism learned from European art – with its emphasis on perspective, anatomical accuracy, volume, and dramatic lighting – to depict scenes and figures from Indian mythology, epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, Puranic legends, and contemporary Indian life.

This fusion was revolutionary. Before Varma, depictions of deities and epic heroes in mainstream Indian art often followed stylized, two-dimensional conventions. Varma rendered these figures with human-like features, emotions, and physical presence, placing them in naturalistic settings. He imbued gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, with a tangible reality that resonated deeply with the Indian populace. His handling of color was rich and vibrant, and his attention to detail, especially in textiles, jewelry, and expressions, was meticulous, adding to the lifelike quality of his canvases.

Iconic Themes and Masterpieces

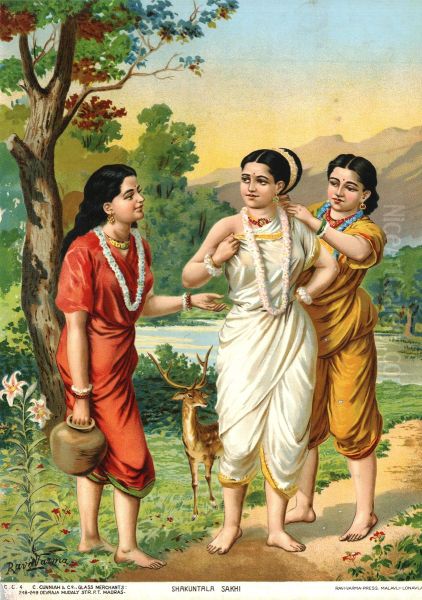

Raja Ravi Varma's oeuvre is vast, but certain themes and works stand out, defining his legacy. He was particularly drawn to depicting pivotal moments from the great Indian epics and Puranas. His portrayals of elegant, often sensuous, female figures became iconic. Among his most celebrated works is Shakuntala, depicting the heroine of Kalidasa's famous play looking back for her lover, Dushyanta, pretending to remove a thorn from her foot – a painting that won acclaim at the Vienna Art Exhibition in 1873.

Other seminal works include Damayanti and the Swan, capturing the pensive princess conversing with the celestial messenger; Lady in the Moonlight, showcasing his mastery of light and atmosphere; Nair Lady Adorning Her Hair, a sensitive portrayal of everyday aristocratic life in Kerala; and the charming domestic scene There comes Papa. He painted numerous versions of deities like Lakshmi and Saraswati, which became standard representations in popular religious art. His epic series included dramatic scenes like Jatayu Vadham (The Slaying of Jatayu) and portraits of mythological figures like Arjuna, Draupadi, Nala, and Damayanti. He was also a sought-after portraitist, capturing the likenesses of Indian royalty, British administrators, and prominent citizens with dignity and realism, comparable in skill to contemporary European portraitists working in India.

The Ravi Varma Press: Art for the Masses

Perhaps one of Ravi Varma's most significant contributions, beyond his individual paintings, was his pioneering effort to make art accessible to the public. Recognizing the immense popularity of his works and desiring to share them widely, he established a lithographic printing press in Ghatkopar, Mumbai, in 1894, later shifting it to Malavli near Lonavala. This venture, known as the Ravi Varma Fine Arts Lithographic Press, was set up with the assistance of his brother, C. Raja Raja Varma, and collaborator Goverdhandas Khatau Makanji.

The press employed German technicians, including a key figure named Schleicher, and utilized the technique of oleography (color lithography) to produce affordable copies of his paintings. These prints, depicting gods, goddesses, epic scenes, and beautiful women, flooded the Indian market. They adorned the walls of homes, shops, and temples across the country, becoming integral to popular visual culture, religious practice, and even early advertising (calendar art). While some critics later lamented the mass production as potentially diluting artistic merit, the press undeniably democratized art in India on an unprecedented scale, making Ravi Varma a household name and his imagery synonymous with Hindu iconography for millions. The press was eventually sold due to financial difficulties and later destroyed in a fire, adding another layer to its storied history.

Collaboration and Artistic Circle

While Raja Ravi Varma was the principal creative force, his artistic journey was not solitary. His most significant collaborator was his younger brother, C. Raja Raja Varma (1860-1905). C. Raja Raja Varma was an accomplished artist in his own right, particularly skilled in landscape painting. He often accompanied Ravi Varma on his travels, managed his affairs, maintained his diaries (which are invaluable historical resources), and assisted him in the studio. They worked together on several commissions, including a major project of 14 Puranic paintings for the Durbar Hall of the Laxmi Vilas Palace in Baroda (Vadodara) between 1888 and 1889. Their Mumbai studio produced numerous portraits of European and Indian elites.

Varma's artistic influence extended within his family. His sister, Mangalabai Thampuratty, was also a talented painter, particularly known for her portraits, though less famous than her brothers. His nephew, K. R. Rama Varma, also followed in his footsteps, adopting elements of his style. Beyond his family, Varma's work created ripples across the Indian art scene. While he didn't run a formal school, his success inspired many. Contemporaries like M. V. Dhurandhar, also known for mythological and historical scenes, worked during the same period, sometimes reflecting similar academic influences. Portraitists like Pestonji Bomanji and Antonio Xavier Trindade were active in Bombay, representing different facets of the evolving art scene. Even early photographers like Lala Deen Dayal captured the likenesses of royalty and elites, a field that paralleled the demand for painted portraits Varma fulfilled. J. B. Dikshit was another artist associated with working at the Ravi Varma Press.

Accolades and Recognition

Raja Ravi Varma achieved considerable fame and recognition both within India and internationally during his lifetime. His participation in major exhibitions brought him numerous accolades. As mentioned, his painting Shakuntala Removing a Thorn from her Foot (though sometimes other works are cited for this award) won the Governor's Gold Medal at the Madras Fine Arts Exhibition and an award at the International Art Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. He was also awarded medals at the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893.

His patrons included numerous Indian Maharajas, Dewans (prime ministers), and wealthy industrialists, who commissioned portraits and large mythological canvases. The British colonial administration also acknowledged his stature. In 1904, Viceroy Lord Curzon, on behalf of the British Emperor, awarded him the prestigious Kaiser-i-Hind Gold Medal for his services to art. This official recognition cemented his position as the preeminent Indian artist of his era. His aristocratic background, combined with his immense talent and widespread popularity, made him a celebrated figure in Indian society.

Controversies and Criticisms

Despite his immense popularity and success, Raja Ravi Varma's work was not without controversy, both during his lifetime and in subsequent critical assessments. His fusion of styles, while groundbreaking, drew criticism from different quarters. Some Indian traditionalists and later nationalist critics felt his work was overly Westernized, lacking the spiritual depth and stylistic purity of indigenous art forms. They argued that his realistic portrayal of deities humanized them excessively, stripping them of their divine mystery. Figures like Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, pioneers of the Bengal School of Art, consciously reacted against Varma's style, seeking inspiration in Ajanta murals, Mughal miniatures, and Japanese wash techniques to forge what they considered a more authentically "Indian" modern art.

Furthermore, Varma's depictions of voluptuous, often scantily clad, women from mythology, such as celestial nymphs (apsaras) like Rambha and Urvashi, or figures like Damayanti, sometimes drew accusations of vulgarity and offended conservative sensibilities. He even faced an obscenity lawsuit in Bombay in the late 1890s, charged with hurting religious sentiments through his realistic and sometimes sensual portrayals of mythological figures in his widely circulated prints, though he was eventually acquitted. Critics also pointed out that his models were often South Indian women, leading to a certain homogenization in the depiction of figures from diverse regions of India. The term "kitsch" has sometimes been applied to the mass-produced prints, suggesting a decline into sentimentality or commercialism.

Later Life and Death

In his later years, Raja Ravi Varma continued to paint, but his output may have slowed due to age and possibly declining health, compounded by the challenges of managing the press and dealing with controversies. His brother and close collaborator, C. Raja Raja Varma, passed away in 1905, which was undoubtedly a significant personal and professional loss. Raja Ravi Varma himself suffered from diabetes. He passed away on October 2, 1906, at his Kilimanoor Palace, at the age of 58. His death was widely mourned, marking the end of an era in Indian art.

Legacy and Market Presence

Raja Ravi Varma's legacy is multifaceted and profound. He fundamentally altered the course of modern Indian art by introducing oil painting and academic realism on a grand scale, applying them to Indian themes. His works provided a visual vocabulary for Indian mythology and history that influenced not only subsequent generations of artists but also popular culture, including early Indian cinema (Dadasaheb Phalke, the father of Indian cinema, reportedly worked at the Ravi Varma Press for a time), theatre set design, calendar art, and commercial advertising. The 2014 film Rang Rasiya (Colours of Passion) dramatized his life, highlighting his art, his muses, and the controversies surrounding him.

His paintings remain highly sought after by collectors and institutions. Due to their historical significance, many of his major works are considered national treasures. In 1979, the Indian government declared his works as such under The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, restricting their export. This rarity, combined with their artistic merit, has driven prices to astronomical levels in the auction market. Works occasionally surface internationally, commanding high prices. For instance, his painting Radha in the Moonlight fetched a record price (reportedly around US.95 million or over 20 crore Rupees at the time) at a Pundole's auction in Mumbai. Even his oleographs, once affordable prints, are now valuable collectibles. The recent foray of his works into the digital realm, with NFTs of his oleographs being auctioned (like those on the RtistiQ platform in February 2022), demonstrates the enduring appeal and adaptability of his imagery in the contemporary market.

Conclusion: A Complex Icon

Raja Ravi Varma remains a pivotal, albeit complex, figure in Indian art history. He was an innovator who skillfully navigated the cultural confluence of colonial India, creating a visual language that was both modern and deeply rooted in Indian tradition. His ability to render the epic and the divine with relatable humanism, combined with his entrepreneurial spirit in disseminating his art through the press, ensured his pervasive influence. While debates about the aesthetic merits of his style versus later nationalist art movements continue, his role in shaping modern Indian visual culture is undeniable. He brought Indian gods and heroes out of the temple and manuscript into the everyday lives of the people, leaving behind a legacy that continues to be celebrated, debated, and cherished. His paintings are more than just artworks; they are cultural artifacts that reflect a nation's journey towards modernity and self-discovery.