John Singleton Copley stands as a pivotal figure in eighteenth-century art, a master craftsman whose career uniquely bridged the burgeoning artistic landscape of colonial America and the established traditions of Great Britain. Born in or near Boston, Massachusetts, likely on July 3, 1738, he rose from modest beginnings to become the most sophisticated and sought-after portraitist in the American colonies before embarking on a successful, albeit different, career in London as a painter of historical subjects and fashionable portraits. His life and work offer a fascinating study in artistic development, cultural transition, and the complexities of identity during a revolutionary era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Boston

Copley's origins were humble. His parents, Richard and Mary Singleton Copley, were immigrants of Irish descent who ran a tobacco shop on Long Wharf in Boston. Richard Copley died around the time of John's birth, leaving Mary to raise her son. Around 1748, Mary Copley married Peter Pelham, an established English engraver, portraitist, and schoolmaster who had settled in Boston. This union proved crucial for the young Copley's future.

Pelham provided Copley with a basic education, likely teaching him reading, writing, and arithmetic. More importantly, he introduced his stepson to the world of art and craft. Pelham's profession as an engraver, particularly his work producing mezzotints after portraits by other artists, exposed Copley to European artistic conventions and compositions. Living in a household actively engaged in the visual arts, Copley absorbed techniques and likely received direct instruction from Pelham, although the extent of this formal training is unclear.

Boston in the mid-eighteenth century possessed a nascent but growing artistic community. Copley had access to the works of earlier colonial painters, most notably John Smibert, a Scottish-born artist who had arrived in 1729. Smibert's studio contained copies of Old Master paintings and casts of classical sculptures, offering a rare window into European art for aspiring colonial artists. Copley undoubtedly studied Smibert's portraits, learning from his compositions and techniques, even as he quickly surpassed Smibert's abilities.

Another significant early influence was Joseph Blackburn, an English painter who worked in Boston from 1755 to 1763. Blackburn brought with him a more fluid, Rococo style, characterized by lighter palettes, graceful poses, and attention to the textures of fine fabrics. Copley met Blackburn around 1755 and rapidly assimilated elements of his more fashionable style, particularly the elegant rendering of silks and satins and the use of graceful, S-curve poses, moving beyond the somewhat stiffer linearity inherited from Smibert and earlier colonial traditions.

Despite these influences, Copley was largely self-taught. He learned by observing the works of others, studying anatomical books and European prints, and through relentless practice. His stepfather's death in 1751, when Copley was only thirteen, meant he had to forge his own path early on. By his mid-teens, he was already working professionally, initially producing portraits and even attempting mythological scenes, demonstrating remarkable precocity and ambition.

The Premier Portraitist of Colonial America

By the late 1750s and early 1760s, Copley had established himself as the leading portrait painter in Boston, surpassing his local predecessors and contemporaries like Robert Feke and Joseph Badger. His reputation quickly spread throughout the colonies, leading to commissions from New York City and Philadelphia. His success stemmed from an extraordinary ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the material reality and psychological presence of his sitters.

Copley's American portraits are renowned for their striking realism, meticulous attention to detail, and palpable sense of presence. He rendered faces with unflinching honesty, capturing individual character without excessive flattery. His depiction of textures – the gleam of polished wood, the softness of velvet, the crispness of linen, the cold sheen of metal – was unparalleled in colonial art. This intense focus on materiality resonated with his patrons, often prosperous merchants, clergymen, and artisans, whose status was closely tied to their worldly possessions.

He often employed the convention of portraiture d'apparat, incorporating objects associated with the sitter's profession or interests to add narrative depth. A prime example is his iconic portrait of Paul Revere (c. 1768-70). Revere, the silversmith and revolutionary figure, is shown in his shirtsleeves, holding a silver teapot and contemplating its design, surrounded by the tools of his trade. The portrait is remarkable for its directness, informality, and celebration of artisanal skill, a departure from more formal European conventions.

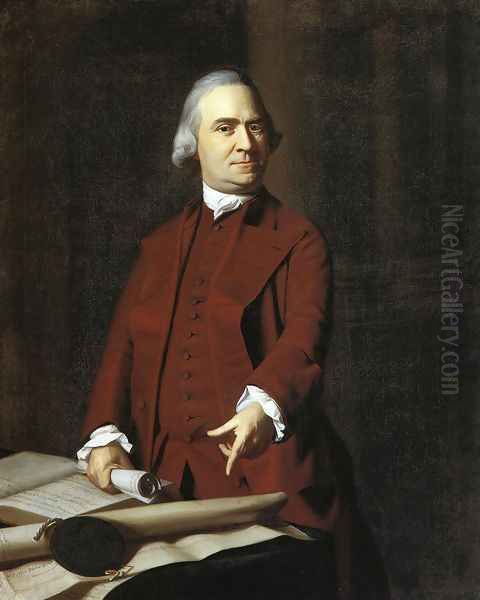

Other key works from this period demonstrate his range and insight. The portrait of Mercy Otis Warren (c. 1763) captures the intelligence and refinement of the writer and political commentator. His depiction of Samuel Adams (c. 1772), commissioned by John Hancock, presents the fiery revolutionary pointing to the Massachusetts Charter, embodying defiance and principle. These portraits were not mere likenesses; they were powerful statements about identity, status, and the values of colonial society.

Copley's technique involved careful drawing, thin layers of paint, and precise brushwork, creating smooth, highly finished surfaces. He masterfully manipulated light and shadow to model form and create a sense of volume, making his figures appear solid and three-dimensional. While influenced by European styles, his American work retained a distinctive linear quality and sharp focus, often described as uniquely "American" in its directness and lack of affectation.

Transatlantic Ambitions and Departure

Despite his unparalleled success in the colonies, Copley felt artistically isolated. He yearned for exposure to the great art of Europe and sought validation from the London art establishment. In 1766, he took a significant step by sending his painting Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham) (1765) – a charming portrait of his half-brother – to the annual exhibition of the Society of Artists in London.

The painting was received with considerable interest. Benjamin West, an American painter who had already established a successful career in London, praised its skillful execution but advised Copley to study abroad to refine his style, noting a certain "hardness" and lack of atmospheric depth compared to prevailing European tastes. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the influential president of the Royal Academy, echoed this sentiment, encouraging Copley to make the journey to Europe before his manner became too fixed.

This feedback confirmed Copley's own desire to broaden his horizons. However, personal and professional commitments, including his marriage in 1769 to Susanna Farnham Clarke, daughter of a wealthy Loyalist merchant, delayed his departure. The escalating political tensions in Boston also played a crucial role. Copley tried to remain neutral, painting portraits of both Patriots (like Adams and Hancock) and Loyalists (like his father-in-law Richard Clarke, whose warehouse stored the tea destroyed in the Boston Tea Party). As conflict became inevitable, his position grew increasingly precarious.

In June 1774, driven by artistic ambition and the volatile political climate, Copley finally sailed for England, leaving his wife and children temporarily behind. He intended to undertake a Grand Tour of Europe before settling in London. He would never return to America.

The Grand Tour and Artistic Re-Education

Copley's European tour, lasting from 1774 to 1775, was a transformative experience. He traveled first to London, where he met West and Reynolds and viewed contemporary British art. He then journeyed to Paris and onward to Italy, spending significant time in Rome, Florence, and Naples. This was his first direct encounter with the masterpieces of antiquity and the Renaissance, works he had previously known only through prints.

In Italy, he diligently studied and sketched classical sculptures and paintings by masters like Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and Correggio. He sought to absorb the principles of the "Grand Manner" – the elevated style favored by the European academies, emphasizing idealized forms, noble subjects, complex compositions, and historical or mythological themes. He also encountered the burgeoning Neoclassical movement, particularly through the work of artists like Anton Raphael Mengs and Pompeo Batoni in Rome.

During his time in Rome, he painted the ambitious double portrait Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Izard (1775). This work shows the wealthy South Carolina couple surrounded by classical artifacts, demonstrating Copley's attempt to integrate his newfound knowledge of European art and Neoclassical aesthetics into his portraiture. While technically accomplished, the painting reveals the challenges he faced in reconciling his innate realism with the idealized conventions of the Grand Manner.

The Grand Tour fundamentally altered Copley's artistic perspective. He consciously sought to shed the perceived provincialism of his colonial style and adopt a more sophisticated, painterly approach aligned with European expectations. This involved loosening his brushwork, softening his contours, and paying greater attention to atmospheric effects.

A New Career in London: Portraits and History Painting

In late 1775, Copley reunited with his family (who had fled Boston) and settled permanently in London. He quickly set about establishing his reputation in the highly competitive London art world, dominated by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and George Romney. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy of Arts and was elected an associate member in 1776, achieving full academician status in 1779, a testament to his rapid acceptance.

His London career saw him working in two primary genres: portraiture and history painting. His London portraits differed noticeably from his earlier American work. They were generally larger, more elaborate, and adopted the fashionable poses and settings of the British elite. Works like The Copley Family (1776-77), a large group portrait depicting himself, his wife, children, and father-in-law, showcase this transition. It combines intimate observation with a more complex, dynamic composition and softer brushwork than his Boston portraits, aiming for a blend of domesticity and social grace.

While his London portraits brought him commissions, it was his history paintings that truly cemented his fame in Britain. History painting – the depiction of significant events from history, mythology, or literature – was considered the highest genre by the academies. Copley brought a unique perspective to this field, often choosing dramatic contemporary events and rendering them with a realism and intensity derived from his portraiture background.

Masterpieces of History Painting

Copley's first major history painting, Watson and the Shark (1778), caused a sensation when exhibited at the Royal Academy. Commissioned by Brook Watson, it depicted a real event from Watson's youth in Havana harbor in 1749, when he lost his leg in a shark attack. Copley transformed this gruesome incident into a powerful allegory of struggle, terror, and salvation. The painting's dramatic composition, realistic depiction of the shark and figures, and exploration of themes of human vulnerability and resilience marked it as a precursor to Romanticism. Its success was instrumental in his election to the Royal Academy.

He followed this triumph with The Death of the Earl of Chatham (1779-81), a large group portrait commemorating William Pitt the Elder's fatal collapse in the House of Lords. This complex work involved painting accurate portraits of over fifty peers, combining the demands of portraiture with the grandeur of historical narrative. Its public exhibition was a commercial success, further enhancing Copley's reputation.

Perhaps his most acclaimed history painting is The Death of Major Peirson (1783). This dynamic and heroic composition depicts the battle for St Helier, Jersey, in 1781, focusing on the moment the British commander, Major Francis Peirson, is killed just as his troops secure victory against French invaders. Copley masterfully orchestrates a complex scene filled with action, pathos, and patriotic fervor, employing dramatic lighting and a swirling composition. The inclusion of a Black servant firing vengefully at the sniper who shot Peirson adds a layer of complexity, though his exact role and identity remain debated.

Copley also undertook the monumental The Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar, September 1782 (1783-91). Commissioned by the City of London, this enormous canvas (over 25 feet wide) depicted a key British naval victory. The project consumed much of his energy and finances for years, involving meticulous research and numerous preparatory studies. While impressive in scale and ambition, its completion was fraught with difficulties, and its critical reception was mixed.

These history paintings showcased Copley's ability to manage complex compositions, conduct thorough research, and infuse historical events with dramatic intensity and psychological depth. He effectively created a new type of contemporary history painting that combined reportorial accuracy with artistic license, influencing subsequent artists in Britain and America, including fellow American expatriate Benjamin West, whose own The Death of General Wolfe (1770) had paved the way for depicting contemporary history in modern dress.

Style Evolution and Analysis

Copley's artistic journey involved a significant stylistic evolution. His American style was characterized by:

Linearity and Sharp Focus: Clear outlines and precise rendering of details.

Empirical Realism: An unvarnished, direct portrayal of the sitter's appearance and character.

Materiality: Exceptional skill in depicting the textures of surfaces – fabric, wood, metal.

Strong Modeling: Use of light and shadow to create a sense of solid, three-dimensional form.

Psychological Insight: Capturing the personality and inner life of the sitter.

Upon moving to London and absorbing European influences, his style shifted towards:

Painterly Brushwork: Looser, more visible brushstrokes, creating a softer, more atmospheric effect.

Increased Idealization: Conforming more to the Grand Manner ideals of grace and nobility, sometimes sacrificing raw realism.

Complex Compositions: More dynamic arrangements of figures, particularly in history paintings.

Richer Color Palettes: Often employing deeper, more resonant colors influenced by Venetian and Flemish masters.

Emphasis on Movement and Drama: Especially evident in his history paintings.

This transition has been subject to debate among art historians. Some argue that Copley lost the unique power and directness of his American work when he adopted the more conventional and sometimes artificial style favored in London. Others contend that his London work demonstrates increased sophistication, technical virtuosity, and ambition, particularly in the challenging genre of history painting. Artists like Gilbert Stuart, another American who worked in London, also navigated this stylistic tension between American directness and British elegance. Charles Willson Peale, who remained in America, maintained a more straightforward, less Anglicized style throughout his career.

Regardless of preference for one period over the other, Copley demonstrated mastery in both styles. His technical proficiency remained exceptional throughout his career. He possessed a keen eye for observation, a sophisticated understanding of composition, and a remarkable ability to render the human form and the material world. His engagement with contemporaries like Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney, Joseph Wright of Derby, and Angelica Kauffman placed him firmly within the mainstream of the British art world.

Later Years, Legacy, and Historical Position

Despite his considerable success in London, Copley's later years were marked by declining fortunes and health. The immense effort and expense invested in the Gibraltar painting strained his finances. The changing tastes of the art public, moving towards Romanticism and Neoclassicism, perhaps made his style seem less fashionable over time. Commissions became scarcer, and he fell into debt.

His health deteriorated in his final years. According to his daughter, Mary, he faced his end with religious conviction and calmness. John Singleton Copley died in London on September 9, 1815, at the age of 77.

His legacy is immense and complex. In America, he is revered as the greatest painter of the colonial era, an artist who captured the character and aspirations of a society on the cusp of revolution. His American portraits remain iconic images of the period, valued for both their artistic merit and historical significance. They provide invaluable insights into the personalities, social structures, and material culture of colonial America.

In Britain, he is remembered as a significant figure in the Royal Academy during its formative years and a major contributor to the genre of history painting. Works like Watson and the Shark and The Death of Major Peirson are considered landmarks of British art, demonstrating innovation in subject matter and dramatic presentation.

Copley's unique transatlantic career makes him a fascinating case study. He successfully navigated two distinct art worlds, adapting his style while retaining core elements of his artistic identity. He achieved the highest honors in both the colonies and the metropolis. His son, also named John Singleton Copley (1772-1863), pursued a highly successful career in law and politics, eventually becoming Lord Chancellor of Great Britain and being created Baron Lyndhurst, a trajectory far removed from his father's artistic beginnings.

Today, Copley's works are held in major museums across the United States and Great Britain, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (which holds the largest collection of his American work), the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and Tate Britain. He remains a subject of scholarly interest, recognized for his technical brilliance, psychological acuity, and his crucial role in the development of both American and British art during a period of profound historical change. He stands as a testament to the talent that emerged from the American colonies and made a lasting impact on the international stage.