Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn stands as a colossus in the annals of Western art. Born during the Dutch Golden Age, a period of extraordinary wealth, scientific discovery, and cultural flourishing in the Netherlands, Rembrandt became its most celebrated artistic exponent. His life, marked by early success, profound personal tragedy, and later financial hardship, is mirrored in the depth and emotional complexity of his work. As a painter, draughtsman, and etcher, his mastery over light and shadow, his unflinching psychological insight, and his innovative techniques left an indelible mark on European art history, influencing generations of artists that followed.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Leiden

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born on July 15, 1606, in Leiden, a prosperous city in the Dutch Republic. He was the ninth child of Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn, a well-to-do miller, and Neeltgen Willemsdochter van Zuijtbrouck, the daughter of a baker. His family's comfortable circumstances allowed for a good education, and at the age of perhaps 13 or 14, Rembrandt was enrolled in the Latin School, with the likely intention that he would eventually attend Leiden University, one of Europe's most prestigious institutions.

However, young Rembrandt's passion lay not in classical studies but in art. He showed little enthusiasm for academic pursuits and demonstrated a clear aptitude for drawing. Recognizing his talent and inclination, his parents allowed him to leave the Latin School to pursue an artistic apprenticeship. He briefly enrolled at Leiden University, possibly studying theology or simply registering as was common for certain privileges, but his true education began in the studios of local artists.

His first significant teacher was Jacob Isaacsz van Swanenburgh, a Leiden painter known for his architectural scenes and depictions of hell. Under Swanenburgh, likely from around 1621 to 1623/24, Rembrandt would have learned the fundamentals of painting technique – grinding pigments, preparing panels, and basic composition. While Swanenburgh's style differed greatly from Rembrandt's later work, this initial training provided a necessary foundation.

Seeking more advanced instruction, particularly in the popular genre of history painting, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam around 1624 or 1625 for a crucial six-month period. There, he studied with Pieter Lastman, a highly respected artist who had traveled to Italy and absorbed the influence of artists like Adam Elsheimer and, indirectly, the dramatic realism of Caravaggio. Lastman specialized in historical and biblical scenes rendered with rich color, attention to detail, and expressive figures. This brief but intense period under Lastman profoundly shaped Rembrandt's artistic direction, instilling in him a love for narrative subjects and dramatic composition that would remain throughout his career.

After completing his training with Lastman, Rembrandt returned to Leiden around 1625, now equipped with the skills and ambition to establish himself as an independent master. He opened his own studio, possibly sharing it initially with his friend and fellow artist Jan Lievens, another former pupil of Lastman. During these Leiden years (c. 1625-1631), Rembrandt rapidly developed his own distinctive style, characterized by strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), textural experimentation, and a keen interest in capturing individual character and emotion, even in his early biblical scenes and portraits. Works from this period, such as The Stoning of Saint Stephen (1625) and Judas Repentant, Returning the Pieces of Silver (1629), already display the dramatic intensity and psychological depth that would become his hallmarks.

Amsterdam: Fame, Fortune, and Family

Around 1631 or 1632, Rembrandt made the decisive move to Amsterdam, the vibrant commercial and cultural heart of the Dutch Republic. The city offered far greater opportunities for patronage and commissions than Leiden. He initially lodged with the art dealer Hendrick van Uylenburgh, whose cousin, Saskia van Uylenburgh, Rembrandt would marry in 1634. Saskia came from a prominent Frisian family; her father had been a burgomaster (mayor) and lawyer. This marriage brought Rembrandt not only companionship but also enhanced social standing and potentially useful connections.

Amsterdam quickly recognized Rembrandt's exceptional talent. His arrival coincided with a booming demand for portraiture among the city's wealthy merchant class. Rembrandt's ability to capture not just a likeness but the sitter's personality and inner life set him apart. His 1632 group portrait, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, was a major breakthrough. Commissioned by the Amsterdam Surgeons' Guild, it revolutionized the genre by depicting the members dynamically interacting around the cadaver, rather than posing stiffly. The painting showcased his mastery of composition, light, and psychological portrayal, cementing his reputation as the city's leading portraitist.

The 1630s were a period of immense productivity and success for Rembrandt. Commissions poured in for individual and group portraits, biblical scenes, and mythological subjects. He ran a large and busy workshop, attracting numerous talented pupils eager to learn his style. His income was substantial, allowing him and Saskia to live comfortably and begin collecting art and curiosities. He produced iconic works like the flamboyant Self-Portrait (1640) now in London's National Gallery, and numerous tender portraits of Saskia.

His family life during this period was marked by both joy and profound sorrow. Rembrandt and Saskia had four children, but tragically, their first three – Rumbartus and two daughters both named Cornelia – died in infancy. Only their fourth child, Titus, born in 1641, survived into adulthood. These personal losses undoubtedly deepened Rembrandt's understanding of human vulnerability and suffering, themes often explored in his art. Saskia herself suffered from ill health, possibly tuberculosis, and died in 1642, just a year after Titus's birth, leaving Rembrandt a widower at the age of 36. Her death marked a turning point in his personal life and, some argue, subtly influenced the emotional tenor of his subsequent work.

The Height of Success and 'The Night Watch'

The period leading up to and immediately following Saskia's death represents the peak of Rembrandt's public fame and professional success. His workshop flourished, and he received prestigious commissions. The most famous of these, and arguably his most ambitious work, was the group portrait commissioned by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and his civic militia company, completed in 1642. Popularly known as The Night Watch (though its title is Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq), the painting is a monumental and revolutionary depiction of a militia group preparing to march out.

Instead of the conventional static arrangement, Rembrandt created a dynamic scene full of movement, dramatic lighting, and individual characterization. Figures emerge from deep shadow into brilliant light, weapons glint, a drum sounds, and a dog barks. The sheer energy and innovative composition were unprecedented. While later legends suggested the painting was poorly received and damaged his career, contemporary evidence indicates it was largely admired, although perhaps some sitters were less pleased than others if their faces were obscured by the dynamic action or deep shadows. The painting's immense scale and complexity affirmed Rembrandt's status as the most innovative painter in Amsterdam.

During the 1630s and early 1640s, Rembrandt also continued to explore biblical and historical themes with increasing depth. Works like The Blinding of Samson (1636) showcase his mastery of Baroque drama and violence, while paintings like The Holy Family with Angels (1645) reveal a growing tenderness and intimacy. His etchings from this period also reached new heights of technical brilliance and expressive power, covering a wide range of subjects from portraits and self-portraits to biblical narratives and everyday scenes.

Artistic Style: Chiaroscuro, Texture, and Emotion

Rembrandt's artistic style is immediately recognizable, primarily due to his masterful use of light and shadow, a technique known as chiaroscuro. Inspired perhaps initially by the Italian master Caravaggio (though likely through Utrecht Caravaggisti like Gerard van Honthorst or Hendrick ter Brugghen, and his teacher Lastman), Rembrandt took chiaroscuro to new levels of psychological and emotional expressiveness. Light in his paintings is rarely just illumination; it directs the viewer's eye, highlights key figures or details, creates dramatic tension, and suggests spiritual significance. Deep, velvety shadows conceal as much as they reveal, adding mystery and depth.

Beyond light, Rembrandt was a master of texture. Especially in his later works, he applied paint thickly, using a technique called impasto, sometimes sculpting the paint with his brush handle or even his fingers. This created tangible surfaces that catch the light, suggesting the richness of fabrics, the roughness of skin, or the glint of metal. This textural richness contrasts with smoothly painted areas, adding another layer of visual interest and realism. His early works often display meticulous detail and fine brushwork, reflecting the Leiden 'fijnschilder' (fine painter) tradition to some extent, but his style evolved towards greater breadth and freedom.

Central to Rembrandt's art is his profound humanism and psychological insight. Whether painting a wealthy merchant, a biblical prophet, or himself, he sought to convey the inner life of his subjects. His portraits go beyond mere likeness to explore character, mood, and experience. In his narrative scenes, he focused on the emotional core of the story, depicting moments of revelation, grief, tenderness, or contemplation with unparalleled empathy. He often chose ordinary-looking people as models for his biblical figures, grounding sacred stories in relatable human experience. This focus on emotional truth and psychological depth distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries.

His versatility was also remarkable. While renowned for portraits and biblical scenes, he also produced landscapes (particularly in his etchings), mythological subjects, genre scenes, and studies of animals. His output across painting, etching, and drawing demonstrates an inexhaustible curiosity and a relentless drive to explore the possibilities of each medium.

Etching and Drawing: Mastery in Graphic Arts

While celebrated as a painter, Rembrandt was equally innovative and influential as a printmaker, specifically an etcher. He approached etching not merely as a means of reproducing his paintings but as an independent art form with its own unique expressive potential. He mastered the technique, experimenting with different types of lines, cross-hatching, and the use of drypoint (scratching directly onto the copper plate for a rich, burred line) to achieve extraordinary effects of light, shadow, and texture.

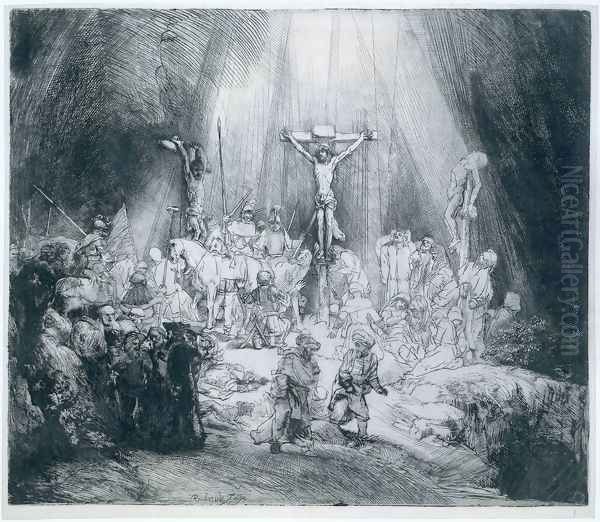

His etched work covers the full range of his subject matter: penetrating self-portraits, portraits of family and patrons, biblical scenes rendered with dramatic intensity or quiet intimacy, genre studies of beggars and street life, and evocative landscapes. Prints like The Hundred Guilder Print (c. 1649), depicting Christ healing the sick, are masterpieces of complex composition and emotional range. The Three Crosses (1653, reworked c. 1660) exists in several states, showing Rembrandt dramatically altering the plate to create increasingly dark and visionary interpretations of the Crucifixion. His landscape etchings, such as The Three Trees (1643), capture the Dutch countryside with atmospheric depth.

Rembrandt's etchings were highly sought after during his lifetime and played a significant role in spreading his fame throughout Europe. They allowed his work to reach a wider audience than his paintings alone could. Today, his graphic work is considered equal in importance to his paintings.

His drawings also reveal his genius. Numbering around two thousand, they served various purposes: preparatory studies for paintings and etchings, rapid sketches capturing observations from life, finished works in their own right, and teaching tools for his pupils. Executed primarily in pen and ink, often with washes of brown ink (bistre) and touches of white heightening, his drawings are characterized by their expressive energy, economy of line, and ability to capture movement and emotion with remarkable immediacy. They offer intimate glimpses into his creative process and his constant observation of the world around him.

Personal Turmoil and Financial Decline

Following Saskia's death in 1642, Rembrandt's personal life became more complicated. He hired Geertje Dircx, the widow of a trumpeter, as a nursemaid for his young son Titus. Geertje soon became Rembrandt's lover. Their relationship ended acrimoniously around 1649. Geertje sued Rembrandt for breach of promise (presumably of marriage) and was awarded alimony. Rembrandt later maneuvered to have her confined to a house of correction (a workhouse or spinhuis) in Gouda for several years, an episode that reflects poorly on his character.

By the late 1640s, Hendrickje Stoffels, a younger woman who had initially entered his household as a servant, became his common-law wife and lifelong companion. Because Saskia's will stipulated that Rembrandt would lose control of her considerable inheritance if he remarried, he and Hendrickje never formally wed. This did not prevent them from living as a family. Hendrickje bore him a daughter, Cornelia, in 1654. Their relationship outside of marriage led to Hendrickje being summoned before the church council and censured for "living in sin" with the painter, a public rebuke she bore with dignity. She remained devoted to Rembrandt until her death, likely from the plague, in 1663.

Despite his continued artistic activity, Rembrandt's financial situation deteriorated significantly from the late 1640s onwards. His income from commissions may have decreased, perhaps due to changing tastes favouring a more elegant, classical style, or perhaps because his increasingly personal and uncompromising later style appealed to fewer patrons. Compounding this was his lifelong habit of extravagant spending. He had purchased a large, expensive house on the Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam in 1639 (now the Rembrandt House Museum), and he was an avid, often reckless, collector of art, antiquities, costumes, and natural curiosities.

His debts mounted, and by 1656, Rembrandt was forced to apply for 'cessio bonorum', a form of voluntary bankruptcy, to avoid imprisonment for debt. An inventory of his possessions taken in 1656 reveals the astonishing range of his collections but also the scale of his financial problems. His house, art collection, and printing plates were auctioned off over the next few years to satisfy his creditors, though the proceeds were disappointing. He was forced to move to much humbler rented accommodation on the Rozengracht in the Jordaan district. To protect him from further financial claims, Hendrickje and Titus set up an art dealership in 1660, nominally employing Rembrandt. This arrangement allowed him to continue working, but the days of wealth and high living were over.

The Late Style: Introspection and Transcendence

Paradoxically, the period of Rembrandt's personal and financial decline coincided with the creation of some of his most profound and moving works. Freed perhaps from the demands of fashionable portraiture, or driven inwards by his experiences, his late style (roughly from the early 1650s until his death in 1669) is characterized by even greater psychological depth, broader and more expressive brushwork, and a focus on inner contemplation and spiritual resonance.

His late portraits, such as the poignant depiction of his friend Jan Six (1654) or the group portrait The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (De Staalmeesters, 1662), show an unparalleled ability to convey both individual character and collective presence. The Syndics, commissioned by the sampling officials of the drapers' guild, is a masterpiece of subtle interaction and quiet authority, demonstrating that even in his later years, he could produce commissioned works of the highest order when required.

His biblical paintings from this period often explore themes of forgiveness, reconciliation, and quiet endurance. Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654), possibly modeled on Hendrickje, is a deeply moving portrayal of vulnerability and complex emotion. The Return of the Prodigal Son (c. 1661-1669), one of his last and most famous works, is a profound meditation on paternal love and forgiveness, rendered with immense tenderness and solemnity. The figures emerge from deep darkness, illuminated by an inner light, their forms suggested by broad strokes of richly textured paint.

Perhaps the most compelling works of his late period are the self-portraits. Rembrandt painted, etched, and drew himself throughout his career, creating an unparalleled visual autobiography numbering nearly one hundred works. The late self-portraits are unflinching explorations of the aging process and the human condition. He depicted himself without vanity, showing the marks of time, sorrow, and resilience on his face. Works like the Self-Portrait with Two Circles (c. 1665-1669) or the late self-portraits in Cologne and London are powerful testaments to his enduring creativity and profound self-awareness in the face of adversity.

Workshop, Pupils, and Attribution

Rembrandt was a highly sought-after teacher, and his workshop in Amsterdam attracted numerous aspiring artists. Unlike the more structured guild system common elsewhere, Rembrandt's teaching seems to have been relatively informal, with pupils learning by copying his works, assisting on commissions, and developing their own styles under his guidance. His influence was immense, shaping a generation of Dutch painters.

Among his most notable pupils were Govert Flinck and Ferdinand Bol, who initially imitated Rembrandt's style closely before developing successful independent careers in a more elegant, internationally influenced manner. Carel Fabritius, perhaps his most gifted pupil, tragically died young in the Delft gunpowder explosion of 1654 but showed remarkable originality, bridging Rembrandt's style with that of Johannes Vermeer. Other significant pupils included Samuel van Hoogstraten, Nicolaes Maes, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Aert de Gelder (who remained faithful to Rembrandt's late style long after it fell out of fashion), and Philips Koninck.

The success of Rembrandt's workshop and the close stylistic relationship between master and pupils have created significant challenges for art historians regarding attribution. Distinguishing between works by Rembrandt himself, works by pupils under his supervision, works created in his style by independent followers, and later imitations has been a complex and ongoing process. The Rembrandt Research Project, established in 1968, undertook decades of systematic research to clarify the authentic oeuvre, though some of its conclusions remain debated. Regardless of precise attributions, the sheer number of talented artists associated with his studio testifies to his impact as a teacher.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Rembrandt's final years were marked by further personal loss. His beloved Hendrickje died in 1663, and his son Titus, who had married Magdalena van Loo in 1668, died later that same year, likely another victim of the plague. Titus left a posthumous daughter, Titia. Rembrandt himself died on October 4, 1669, in Amsterdam and was buried in an unmarked rented grave in the Westerkerk. He died in relative poverty, but his artistic legacy was immense.

While his expressive late style fell out of favour during the classicizing trends of the late 17th and 18th centuries, his reputation never entirely faded, particularly his fame as an etcher. A major revival of interest began in the 19th century, fueled by Romanticism's appreciation for individualism and emotional expression. Artists and critics rediscovered the power and depth of his work.

His influence on subsequent generations of artists has been profound and wide-ranging. His dramatic use of light and shadow inspired artists from the Spanish master Francisco Goya to the French Romantic Eugène Delacroix. His psychological penetration in portraiture set a benchmark for centuries. His expressive brushwork and emotional intensity resonated strongly with artists like Vincent van Gogh, who considered Rembrandt a supreme master. In the 20th century, artists like Francis Bacon cited Rembrandt's raw portrayal of humanity as a key inspiration.

Today, Rembrandt is universally regarded as one of the greatest artists in history. His works are prized possessions of major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (home to The Night Watch and The Jewish Bride - often considered a late masterpiece depicting Isaac and Rebecca), the Mauritshuis in The Hague (The Anatomy Lesson, late self-portraits), the National Gallery in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among many others. Major exhibitions dedicated to his work continue to draw huge crowds, reaffirming his enduring appeal.

Conclusion: The Soul Laid Bare

Rembrandt van Rijn's life journey, from celebrated prodigy to bankrupt master, mirrors the dramatic contrasts found in his art. He navigated the heights of fame and the depths of personal loss, pouring his experiences, observations, and profound empathy into his work. His unparalleled mastery of light and shadow served not just aesthetic ends but illuminated the complexities of the human spirit. He captured the weight of existence, the tenderness of love, the quiet dignity of age, and the drama of sacred stories with an honesty and insight that remain deeply affecting.

Through his paintings, etchings, and drawings, Rembrandt laid bare the souls of his subjects, and in doing so, revealed something fundamental about humanity itself. He stands not just as the towering figure of the Dutch Golden Age, alongside contemporaries like Vermeer and Frans Hals, but as a timeless artist whose work continues to speak to us across the centuries with undiminished power and relevance. His legacy is not merely one of technical brilliance but of profound human understanding, forever etched in light and shadow.