Edvard Munch stands as a towering figure in modern art, a Norwegian painter and printmaker whose work delved into the depths of the human psyche with unparalleled intensity. Bridging the gap between late 19th-century Symbolism and early 20th-century Expressionism, Munch's art confronts the raw, often unsettling emotions associated with life, love, anxiety, and death. His legacy is cemented not only by his hauntingly powerful images, most famously The Scream, but also by his profound influence on subsequent generations of artists who sought to express the inner world.

Early Life and Tragic Beginnings

Edvard Munch was born on December 12, 1863, in the small village of Ådalsbruk in Løten, Norway. He was the second of five children born to Christian Munch, a military doctor known for his piety, and Laura Catherine Bjølstad, a woman twenty years younger than her husband, who possessed artistic inclinations. The family, which included Edvard's older sister Sophie, and younger siblings Laura, Inger, and Andreas, moved to the city of Christiania (now Oslo) shortly after his birth.

Tragedy struck the Munch household early and often, casting a long shadow over Edvard's life and art. When Edvard was just five years old, his mother succumbed to tuberculosis in 1868. This devastating loss was compounded nine years later when his beloved sister Sophie, only fifteen, died from the same disease. These experiences with illness and death deeply traumatized the young Munch, instilling in him a lifelong preoccupation with mortality, grief, and the fragility of human existence.

The family atmosphere was further shaped by Christian Munch's intense religious fervor, which sometimes manifested as morbid anxieties and visions that he shared with his children. Edvard himself was a frail child, often ill with bronchitis and rheumatic fever, forcing him to miss school frequently. His own brushes with illness likely heightened his sensitivity to suffering and the precariousness of life. His father, despite the family's artistic connections (including Edvard's uncle, the painter Jacob Munch), disapproved of art as a profession, viewing it as an "unholy trade," creating tension as Edvard's artistic talents began to emerge. His Aunt Karen Bjølstad, who moved in after his mother's death, provided some stability and encouraged his early artistic efforts.

Formative Years and Artistic Awakening

Despite his father's reservations and his own recurring health problems, Munch's artistic calling proved undeniable. In 1879, he briefly enrolled in a technical college to study engineering but abandoned it in 1881, resolving to become a painter. He entered the Royal School of Art and Design in Christiania, where he received formal training. Initially, his work reflected the prevailing styles of Naturalism and Impressionism.

A significant influence during this period was the bohemian circle in Christiania, particularly the writer and anarchist philosopher Hans Jæger. Jæger advocated for radical honesty in art and life, urging artists to paint their own emotional and psychological experiences. This resonated deeply with Munch, pushing him away from detached observation towards a more subjective, soul-baring approach. His early works began to tackle difficult personal themes.

The Sick Child (first version 1885-86), a poignant depiction inspired by his sister Sophie's death, marked a crucial turning point. Its raw emotion, sketchy execution, and focus on psychological pain rather than realistic detail provoked outrage from critics and the public when exhibited. This negative reception, however, solidified Munch's commitment to expressing inner truth, even if it meant defying conventional aesthetics. He declared, "I paint not what I see, but what I saw."

Paris, Berlin, and the Birth of a Style

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Munch traveled extensively, spending significant time in Paris and Berlin during the late 1880s and 1890s. In Paris, he absorbed the influences of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the works of Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. He was drawn to their bold use of color and line to convey emotion and subjective experience, moving further away from Naturalism.

He began experimenting with Symbolism, aiming to visualize internal states and universal human experiences through evocative imagery. This period saw the genesis of his most ambitious project, The Frieze of Life—A Poem about Life, Love and Death. This cycle of paintings aimed to explore the fundamental stages and emotions of human existence, including love, jealousy, melancholy, anxiety, and death. Many of his most famous works originated as part of this series.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1892 when Munch was invited to exhibit his work at the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists). The raw emotional intensity and unconventional style of his paintings caused a massive scandal. Conservative members of the association were appalled, leading to a vote that closed the exhibition after only one week. This "Munch Affair" paradoxically catapulted him to fame within avant-garde circles across Germany and Scandinavia, establishing him as a radical new voice. It also contributed to a split within the Berlin art scene, leading to the formation of the Berlin Secession. Munch remained in Berlin for several years, becoming a key figure in its Symbolist and burgeoning Expressionist milieu.

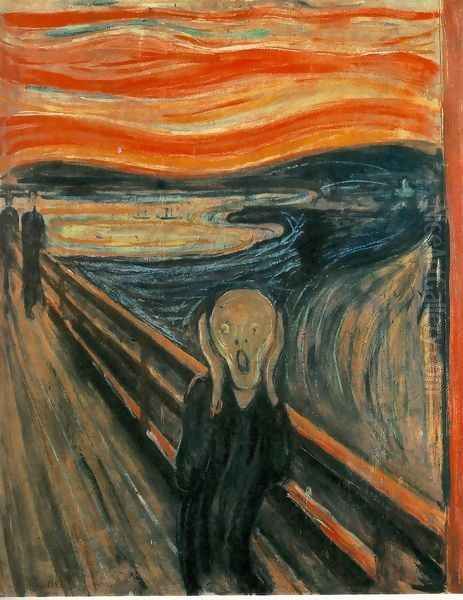

The Scream: An Icon of Modern Angst

Arguably the most recognizable image in modern art, The Scream (first version 1893) epitomizes Munch's artistic vision and the anxieties of the modern age. Created as part of the Frieze of Life, the work exists in several versions, including paintings and prints. Munch described the inspiration in his diary: walking near Christiania at sunset, the sky turned blood red. He felt a "great scream in nature," an overwhelming wave of existential dread and anxiety that seemed to permeate the landscape itself.

The painting translates this intense sensory and emotional experience into visual form. A skeletal, androgynous figure clutches its head, mouth open in a silent shriek, against a backdrop of swirling, fiery sky and a dark, undulating fjord. The distorted forms, jarring colors, and dynamic lines convey a profound sense of inner turmoil and alienation. The figure is often interpreted not just as Munch himself, but as a universal symbol of human suffering, anxiety, and the psychological pressures of modernity. The Scream became a cornerstone of Expressionism, demonstrating the power of art to visualize the deepest, often inexpressible, human emotions.

Exploring the Human Psyche: Key Works and Themes

Beyond The Scream, Munch created a vast body of work exploring the complexities of the human condition, often drawing directly from his own tumultuous life and relationships. The Frieze of Life provided the framework for many powerful images. Madonna (1894-95) presents a controversial, sensual yet ethereal image linking love, life, and death. Vampire (originally titled Love and Pain, 1893-94) depicts a woman with flowing red hair burying her face in a man's neck, an ambiguous image suggesting both solace and destruction in love.

Themes of jealousy and the end of love are explored in works like Ashes (1894), showing a despairing couple in a somber landscape. The Dance of Life (1899-1900) presents figures representing different stages of life and love – youthful innocence, passionate embrace, and solitary withdrawal – set against a moonlit shore. Melancholy (various versions, early 1890s) captures profound loneliness and introspection, often featuring a solitary figure brooding by the sea.

Intimacy and its tensions are central to Kiss (1897), where the faces of the embracing couple merge into a single, unified form, suggesting both connection and loss of individuality. Girls on the Bridge (various versions, starting c. 1901) presents a more lyrical, yet still psychologically charged, scene, often interpreted through the lens of burgeoning womanhood and existential contemplation. Munch was also a master of the self-portrait, using it throughout his life to chronicle his physical and psychological state, as seen in the haunting Self-Portrait with Burning Cigarette (1895).

Mastery of Printmaking

Munch was not only a painter but also a highly innovative and influential printmaker. He embraced techniques like woodcut, lithography, and etching, often using them to revisit and reinterpret themes from his paintings. His approach to printmaking was experimental and expressive, pushing the boundaries of the media.

In his woodcuts, Munch often employed a simplified, powerful style, sometimes sawing his blocks into pieces, inking them separately, and reassembling them like a jigsaw puzzle to achieve complex color prints from a single block. This technique allowed for stark contrasts and bold, flat areas of color, enhancing the emotional impact. His lithographs, like the famous print version of The Scream, captured a sense of immediacy and nervous energy.

Printmaking allowed Munch to disseminate his images more widely, significantly contributing to his influence, particularly on the German Expressionists. Artists of groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Emil Nolde, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), such as Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, admired Munch's emotional directness, bold techniques, and psychological depth. His prints were crucial in shaping the visual language of early 20th-century German art.

Crisis and Recovery

The turn of the century was a period of intense productivity for Munch, but also one of increasing personal turmoil. His relationships were often fraught with conflict, most notably his stormy affair with Tulla Larsen, a wealthy young woman from a respectable family. Their relationship ended dramatically around 1902, allegedly involving a quarrel during which a revolver discharged, injuring Munch's left hand. This event left both physical and emotional scars.

Coupled with heavy drinking and the accumulated stress of his intense emotional life and artistic struggles, Munch suffered a severe nervous breakdown in 1908. He voluntarily checked himself into a clinic in Copenhagen run by Dr. Daniel Jacobson. He spent about eight months there, undergoing rest cures and electrotherapy. Remarkably, he continued to work during his treatment, producing portraits, including one of Dr. Jacobson, and prints.

This period marked a turning point. While his work retained its emotional power, his style shifted somewhat after his recovery. His palette often became brighter and less somber, and his brushwork sometimes looser. While the dark themes never entirely disappeared, there was arguably a greater sense of vitality and a less oppressive atmosphere in some of his later works. The crisis and recovery seemed to bring a new, albeit hard-won, perspective to his art and life.

Return to Norway and Later Years

In 1909, feeling restored, Munch returned to Norway for good. He sought refuge from the pressures of city life and the art world, eventually purchasing several properties, including the estate of Ekely at Skøyen, on the outskirts of Oslo, in 1916. He lived and worked there in relative seclusion until his death.

This later period saw Munch undertake significant public commissions, most notably the murals for the Aula (Assembly Hall) of the University of Oslo (installed 1916). These large-scale works, including the monumental The Sun, displayed a new sense of optimism and decorative power, celebrating nature and knowledge. However, he continued to explore his familiar themes in paintings and prints, often revisiting motifs from the Frieze of Life.

He remained prolific, constantly experimenting and producing numerous landscapes, portraits, self-portraits, and studies of working life. His later self-portraits are particularly poignant, documenting the aging process and his solitary existence with unflinching honesty, such as Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed (c. 1940-43). He suffered from eye trouble in his later years, which affected his vision but did not stop him from working.

During the Nazi occupation of Norway beginning in 1940, Munch lived in fear. Although initially courted by some Nazi officials (like Goebbels), his art was ultimately deemed "degenerate" by the regime. Eighty-two of his works were confiscated from German museums. Fortunately, many were later recovered. Despite the dangers, Munch refused any contact with the occupiers. He died peacefully at Ekely on January 23, 1944, shortly after his 80th birthday.

Legacy and Influence

Edvard Munch's impact on the course of modern art is immense. As a crucial forerunner of Expressionism, he demonstrated that art could be a powerful vehicle for exploring the inner landscape of human emotion, paving the way for artists across Europe, especially in Germany and Austria. His willingness to confront taboo subjects—mental illness, sexuality, death, spiritual angst—opened new territories for artistic exploration.

His technical innovations, particularly in printmaking, were highly influential. The expressive potential he unlocked in woodcut and lithography inspired countless artists. The enduring power of his imagery, especially The Scream, has transcended the art world to become a universal symbol of modern anxiety, referenced and appropriated by artists like Andy Warhol and influencing figures such as Francis Bacon.

Upon his death, Munch bequeathed his vast collection of remaining works—thousands of paintings, prints, drawings, watercolors, and sculptures, along with writings and photographs—to the city of Oslo. This extraordinary gift led to the establishment of the Munch Museum (Munch-museet) in Oslo in 1963, the primary institution dedicated to preserving and exhibiting his life's work.

Edvard Munch remains a compelling and relevant figure because his art speaks directly to fundamental aspects of the human experience. He translated his personal pain and psychological insight into universal statements about life's joys, sorrows, and mysteries. His unflinching honesty and expressive power ensure his place as one of the most important and enduring artists of the modern era.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch's journey was one marked by profound personal loss and psychological struggle, yet it fueled an artistic output of extraordinary emotional depth and innovative power. From the tragic shadows of his youth to the international notoriety sparked by controversy, and finally to the relative seclusion of his later years, Munch consistently channeled his experiences into his art. He dared to paint the unseen – the anxieties, desires, and fears that lie beneath the surface of existence. His legacy is not just a collection of iconic images, but a testament to the power of art to confront the complexities of the human soul, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of modern art that continues to resonate today.